Connecticut Wildlife Nov/Dec 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WMO SURVEY the World Meteorological Organization Is

I [40/19] ADMIRALTY Charts affected by the Publication List ADMIRALTY Charts International Charts 375 INT 750 376 INT 1543 461 INT 1655 863 INT 3199 1481 INT 7017 1797 INT 7018 1859 2045 ADMIRALTY Publications 2246 2583 NP 44 2601 e-NP 44 2837 2847 2858 3166 3545 4410 4411 4491 4735 4737 4738 4739 4787 4791 4792 4921 8275 AUS 680 AUS 683 PNG 680 PNG 683 WMO SURVEY The World Meteorological Organization is conducting a survey regarding the World-Wide Meteorological Information and Warning Service available at: WWW.JCOMM.INFO/MMMS Your participation is GREATLY appreciated and VALUED. denotes chart available in the ADMIRALTY Raster Chart Service series. 1.6 I ADMIRALTY CHARTS AND PUBLICATIONS NOW PUBLISHED AND AVAILABLE NEW ADMIRALTY CHARTS AND PUBLICATIONS New ADMIRALTY Chart published 03 October 2019 Chart Title, limits and other remarks Scale Folio 2019 Catalogue page 461 Bahamas, Ocean Cay. 83 126 Approaches to Ocean Cay. 1:50,000 25° 12´·00 N. - 25° 30´·00 N., 79° 07´·50 W. - 79° 18´·00 W. A Ocean Cay Approach Channel. 1:10,000 25° 24´·500 N. - 25° 25´·750 N., 79° 11´·750 W. - 79° 14´·200 W. B Ocean Cay Cruise Terminal. 1:4,000 25° 24´·750 N. - 25° 25´·100 N., 79° 11´·900 W. - 79° 12´·880 W. A new chart providing improved coverage of Ocean Cay. This chart is referred to WGS84 Datum. Reproductions of Australian Government Charts (Publication dates of these charts reflect the dates shown on the Australian Government Charts) Chart Published Title, limits and other remarks Scale Folio 2019 Catalogue page PNG680 06/09/2019 Papua New Guinea, New Britain, Approaches to Blanche Bay. -

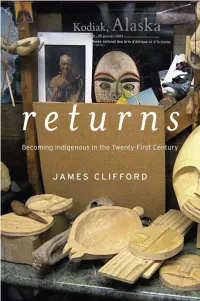

Returns : Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century / James Clifford

RETURNS RETURNS ❖ Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century James Clifford Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clifford, James, 1945– Returns : becoming indigenous in the twenty-first century / James Clifford. pages ; cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-674-72492-1 1. Indigenous peoples. 2. Indigenous peoples—Ethnic identity. 3. Indigenous peoples—Social life and customs. 4. Cultural fusion. I. Title. GN380.C59 2013 305.8—dc23 2013012423 ❖ For my students, 1978–2013 Contents Prologue 1 ParT I 1. Among Histories 13 2. Indigenous Articulations 50 3. Varieties of Indigenous Experience 68 ParT II 4. Ishi’s Story 91 PART III 5. Hau’ofa’s Hope 195 6. Looking Several Ways 213 7. Second Life: The Return of the Masks 261 Epilogue 315 References 321 Sources 345 Acknowledgments 347 Index 349 RETURNS ❖ Prologue Returns is the third volume in a series beginning in 1988 with The Predicament of Culture and followed in 1997 by Routes. Like the others, it collects work written over roughly a decade. Ideas begun in one book are reworked in the others. All the important questions remain open. Returns is thus not a conclusion, the completion of a trilogy. It belongs to a continuing series of reflections, responses to changing times. In ret- rospect, how can these times be understood? What larger historical developments, shifting pressures and limits, have shaped this course of thinking and writing? Situating one’s own work historically, with limited hindsight, is a risky exercise. -

5 Confederation Won Celebration!

063-073 120820 11/1/04 2:34 PM Page 63 Chapter 5 Confederation Won Celebration! With the first dawn of this summer morn- mourning. A likeness of Dr. Tupper is burned ing, we hail the birthday of a new nation. side-by-side with a rat in Nova Scotia. In A united British America takes its place New Brunswick, a newspaper carries a death among the nations of the world. notice on its front page: “Died—at her resi- dence in the city of Fredericton, The Prov- —George Brown ince of New Brunswick, in the 83rd year of her age.” It is 1 July 1867. The church bells start to ring at midnight. Early in the morning guns roar a salute from Halifax in the east to Sarnia in the west. Bonfires and fireworks light up the sky in cities and towns across the new country. It is the birthday of the new Dominion of Canada and the people of Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia are cele- brating. Under blue skies and sunshine, people of all religious faiths gather to offer prayers for the future of the nation. In Toronto, there is a great celebration at the Horticultural Gardens. The gardens are lit with Chinese lanterns. Fresh strawberries and ice cream are served. A concert is followed by dancing. Tickets are 25¢; children’s tickets are 10¢. In another part of the city, a huge ox is roasted and the meat is distributed to the poor. In Québec, boat races on the river, horse races, and a cricket match are held. -

Lesson Resource Kit - Family Ties: Ontario at the Time of Confederation

Lesson Resource Kit - Family Ties: Ontario at the Time of Confederation Grade 8: History and Geography Introduction Designed to fit into teachers’ practice, this resource kit provides links, activity suggestions, primary source handouts and worksheets to assist you and your students in applying, inquiring, and understanding Canada between 1850 and 1914. George, Margaret, and Catherine Brown, ca. 1874 George Brown family fonds F 21-10-0-1 Archives of Ontario, I0073596 Topic Ontario during the Era of Confederation Sources Meet the Browns online exhibit The Black Canadian Experience in Ontario 1834-1914: Flight, Freedom, Foundation online exhibit Documents from the Front: The American Civil War and Fenian Raids in the 1860s online exhibit Family Ties: Ontario Turns 150 onsite exhibit (Sept. 2016 to May 2018) Use the Archives of Ontario’s online and onsite exhibits: o As a learning resource for yourself o As sites to direct your students for inquiry projects o As places to find and use primary sources related to the curriculum Page | 1 Themes that can be addressed Confederation Immigration Political change Ontario’s Indigenous peoples Canada-US relations Residential schools in Ontario The Underground Railroad Curriculum Strand D. Canada, 1945-1982 Strand A. Creating Canada, 1850–1890 Historical Thinking Overall Expectations Specific Expectations Concepts A1. Application: Colonial Continuity and Change; A1.1, A1.2, A1.3 and Present-day Canada Historical Perspective A2. Inquiry: From New Historical Perspective; A2.1, A2.2, A2.4, A2.5, France to British North Historical Significance A2.6 America A3. Understanding Historical Significance; Historical Context: Events A3.4, A3.5 Cause and Consequence and Their Consequences Page | 2 Assignment & Activity Ideas Gather information & discuss Studying the past can seem daunting to a student, if only because they may feel they don’t know where to start. -

A New Franco-American Society – La Bibliothèque Nationale Franco-Américaine

Le FORUM “AFIN D’ÊTRE EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS” VOLUME 34, #3 FALL/AUTOMNE 2009 New Website: francoamericanarchives.org another pertinent website to check out - Franco-American Women’s Institute: http://www.fawi.net $6.00 US Le Forum This issue of Le Forum is dedicated in loving memory to Marie-Anne Gauvin Ce numéro du “Forum” est dédié à la Le Centre Franco-Américain douce mémoire de Marie-Anne Gauvin, voir Université du Maine Orono, Maine 04469-5719 [email protected] page 4... Téléphone: 207-581-FROG (3764) Télécopieur: 207-581-1455 Sommaire/Contents Volume 34, Numéro 3 FALL/AUTOMNE Features Éditeur/Publisher Yvon A. Labbé Letters/Lettres...............................................................................3, 25-27 Rédactrice/Gérante/Managing Editor Lisa Desjardins Michaud L’État du Maine.........................................................4-10, 22, 23, 27, 44 Mise en page/Layout Lisa Desjardins Michaud L’État du Connecticut.....................................................................11-22 Composition/Typesetting Robin Ouellette L’État du Massachusetts......................................................................23 Lisa Michaud Aide Technique L’État du Minnesota.....................................................37, 38, 42, 47, 48 Lisa Michaud Yvon Labbé France-Louisiane..............................................................................50, 54 Tirage/Circulation/4,500 Imprimé chez/Printed by Books/Livres...............................................................................30, -

Mapping the Liberal Impulse: the Primacy of Cartography in the Hudson’S Bay Company’S Imperial Project, 1749- 1857

Mapping the Liberal Impulse: The Primacy of Cartography in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Imperial Project, 1749- 1857 by Michael Cesare Chiarello A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Michael Cesare Chiarello Abstract This research project presents three case studies that illustrate the nature of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) imperial project and how it was guided by liberal impulses and a desire to attain geographic knowledge. There is a specific focus on how spaces were mapped, conceptualized, and rationalized from native, to fur trade, and finally as settler space. Through an emphasis on the early surveying projects of the interior of Rupert’s Land (1749-1805), the establishment of the Red River Settlement (1804-1820), and the 1857 British Parliamentary Inquiry of the HBC, this thesis argues that the desire to seek geographical knowledge was born from an enlightenment yearning to advance scientific understanding of geography through cartography, but was ultimately advanced by the HBC as a means to make the spaces of their imperium into ones that were ordered, secure, rational, and ultimately governable. Map-making projects both defined and ultimately brought to an end the HBC’s imperium in Rupert’s Land. ii Acknowledgments Writing this thesis has been an incredibly rewarding experience for me but it would not have been possible without the help of others. First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. John C. -

Celebrating 20 Years of Travel About Eagle-Eye Tours Tours by Region

2016 Travel Schedule Eagle-Eye Tours Celebrating 20 years of Travel ABOUT EaGLE-EYE TOURS TOURS BY REGION 20 years! potentials. We are offering photo tours to Ecuador, We are thrilled to be celebrating our 20 year Patagonia and Manitoba. These tours include anniversary! We thank all of our past travelers and our instruction to improve your photography, from guides for joining us on this remarkable journey. Now, shooting to final processing of the image. Visit these we are looking ahead to another 20 years of innovative tours online to see examples of our leaders’ images. travel and unforgettable experiences around the globe! Tranquilo tours T New website! Are you looking for tours that offer great birding Our new website is live! Check it out and see while minimizing how often you change locations? what you think. For the latest updates on tour Our Tranquilo tours are a perfect choice. We have offerings and prices, itineraries, maps and more, designed each tour to stay at only one or two great look no further than www.eagle-eye.com. locations. That means less packing and travel, more birding, and more opportunity to relax on the veranda 1% For the Planet watching feeders if you need a little down time. We have joined an elite group of businesses as Look for great options such as Trinidad & Tobago, a member of 1% for the Planet. One percent Dominica & St. Lucia, Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest of our sales to will be donated to nonprofits or Rio Cristalino Lodge, Panama and Argentina. working toward environmental conservation. -

Grenfell of Labrador. London

GRENFELL OF LABRADOR • • < .· Grenfell of Labrador By James Johnston, F.R.H.S. Author of " Missionary Landscapes in the Dark Continent,'' etc, FULLY ILLUSTRATED London S. W. Partridge & Co., Ltd. E.C.4 1tbe man on tbe 1abrat'lot To WILJ't.•D T. GJ.BMJ'BLL Calmly we fare oa the charted coasts By the buoy ancl bell and Ucht; But long ia hi& watch on the Labrador, And keenly he lists for the breakers' roar When the white fog drifts like a troop of ghosts, Or he steers through the murky night. And this is the gift that he brings the souls To whom he steers in the night ; Chart for their voyage o'er life's wild sea, Knowledge of reefs on the beetling lee, News of a Pilot when nearing shoals, And the Bash of a harbour light. Ozou S. DAVIS. Otdltattd To GRENFELL'S MOTHER BY THE AUTHOR Preface I have much pleasure in acceding to the Author's request that I should write a few lines by way of pref~ce to his Life of Dr. Grenfell. It is twenty years since Dr. Grenfell was appointed Superintendent of the work being carried on by the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen in the North Sea and elsewhere round the shores of the British Isles, and from the day he gave himself to the cause of the fisher men his life may be said to have been one long, ceaseless effort to uplift and help the men whose lot he has made his own, and whose perils and hardships he has ever since been sharing. -

The Rebellion of 1837 in Its Larger Setting

THE REBELLION OF 1837 IN ITS LARGER SETTING Presidential Address Delivered by CHESTER W. NEW 1937 In contemplating a topic for this occasion, I found myself confronted at the outset with this question: To what extent is one justified in a presidential address in stating purely individual convictions that may evoke controversy and suggest a break from tradition? Certainly my own strongest conviction in respect to the study and teaching of history in Canada at the present time is that too much emphasis is being placed on Canadian history. On the research side, the reasons for this over emphasis can readily be discerned. The history of Canada has not yet been worked out as satisfactorily as that of other nations and the material for it lies ready to hand; these facts constitute a challenge to productive work. But they should not be permitted to thwart and cripple the interest of our Canadian people in that larger world out of which we have come. A better understanding on the part of Canadians of the history of that larger world is too essential to the development of a broad-visioned national life and of any culture worthy of the name, to be neglected either on account of the exigencies of research on the one hand or the call of a short-sighted patriotism on the other. At this formative stage of our national culture surely there is more patriotism to be served in attempting to rescue the thinking of our people from its provincialism, its isolationism, and the crasser aspects of its materialism, than in focussing their attention on purely Canadian history. -

To See Available Bright Map Cities

Bright Modern Atlas City Selection US Cities -San Diego -Wilmington -Carbondale Alabama (Pink) -San Francisco-Oakland Florida (Yellow) -Champagne - Urbana -Anniston-Oxford -San Jose -Boca Raton -Chicago -Auburn-Opelika -Santa Ana -Clearwater -Danville -Birmingham -Santa Barbara -Daytona Beach -DeKalb -Decatur-Huntsville -Santa Rosa -Fort Lauderdale -East St. Louis -Florence -Stockon -Fort Myers -Evanston -Gadsden -Tahoe -Gainesville -Galesburg -Mobile -Ventura -Jacksonville -Kankakee -Montgomery -Key Largo -Lake Forest -Tuscaloosa Colorado (Purple) -Lake Wales -La Salle - Peru -Aspen -Miami -Naperville Alaska (Green) -Boulder -Naples -Moline -Anchorage -Colorado Springs -Ocala -Morris -Fairbanks -Denver -Orlando -Peoria -Juneau -Durango -Pahokee -Quincy -Ketchikan -Fort Collins -Palm Beach -Rock Falls -Kodiak -Fort Morgan -Panama City -Rockford -Sitka -Grand Junction -Pensacola -Springfield -Greely -Sanibel Island Arizona (Green) -La Junta -St. Augustine Indiana (Yellow) -Bisbee -Montrose -St. Petersburg -Aurora -Douglas -Pueblo -Tallahassee -Bloomington -Flagstaff -Salida -Tampa -Evansville -Globe -Sterling -Winter Haven -Fort Wayne -Grand Canyon -Telluride -Gary -Nogales -Walsenburg Georgia (Purple) -Indianapolis -Phoenix -Albany -Lafayette -Prescott Connecticut (Green) -Atlanta -Muncie -Tucson -Bridgeport -Augusta -New Albany -Winslow -East Haven -Brunswick -South Bend -Yuma -Greenwich -Cartersville -Terre Haute -Hartford -Columbus -Valparaiso Arkansas (Yellow) -Middletown -Dalton -Batesville -Milford -Douglas Iowa (Pink) -Fayetteville -

International Schedule of Territories

IFTA® INTERNATIONAL SCHEDULE OF TERRITORIES IMPORTANT: The following IFTA® Schedule of Territories outlines individual countries, groups of countries and territories, and groups of territories as they are often used for purposes of granting distribution rights for films or television programs. When referenced in the Deal Terms of the IFTA® International Multiple Rights Agreement, the Schedule is incorporated by reference. However, the Schedule may not be appropriate for all media due to the method of distribution. The Schedule is organized in the following three ways: 1) Alphabetical Listing, 2) Geographical Listing, and 3) Language Group Listing. Users should note that the terms in bold refer to and are comprised of all the countries, territories and/or islands listed in the succeeding definition. Users should also note that some of the definitions overlap. The information appearing in this Schedule is based on the most current information available as of the publication date of this Version 2018. IFTA does not assume legal responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information in this Schedule. This is not intended to and cannot replace the need to consult legal counsel. These definitions are subject to change as developments in national boundaries occur. IFTA reserves the right in its sole discretion to change the following definitions at any time as conditions may require. ALPHABETICAL LISTING Africa – Algeria; Angola; Benin (Dahomey); Botswana; Burkina Faso (Upper Volta); Burundi; Cameroon; Cape Verde Islands; Central -

2019 INALJ Jobs Naomi House James Adams, Content Managing Editor Aisha Conner-Gaten, Content Editor- Submissions Formatter

2019 INALJ Jobs Naomi House James Adams, Content Managing Editor Aisha Conner-Gaten, Content Editor- Submissions Formatter 1.11.2019 *** Issue 8.19 *** Sponsored jobs *USA jobs *Canada jobs *International jobs *** SPONSORED Branch Manager (Heritage) / Yuma County Libraries / Yuma, AZ Remove 2/7 Dean of Library Services / The University of Northern Iowa’s Rod Library / Cedar Falls, IA/ Full Consideration Date 2/11 remove 2/8 Dean – University Library 103084) / The American University in Cairo / Cairo, Egypt remove 1/12 USA USA – Virtual Work to find more sites to job hunt at in the virtual sphere check out INALJ Telework –Virtual home page: Alabama to find more sites to job hunt at in AL check out INALJ Alabama home page: Alaska to find more sites to job hunt at in AK check out INALJ Alaska home page: Arizona to find more sites to job hunt at in AZ check out INALJ Arizona home page: Sponsored Branch Manager (Heritage) / Yuma County Libraries / Yuma, AZ Arkansas to find more sites to job hunt at in AR check out INALJ Arkansas home page: California to find more sites to job hunt at in CA check out INALJ California home page: Library Assistant / California State University San Marcos / San Marcos, CA / Apply by 1/23 Librarian / California State University, Stanislaus / Turlock, CA / Apply by 2/1 Digital Asset Coordinator / Ellation, Inc. / San Francisco, CA Librarian / Monterey County Free Libraries / Monterey, CA / Apply by 2/8 User Research Manger / eBay Inc / San Francisco, CA Head