A Grazing Gomphotherium in Middle Miocene Central Asia, 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Species of Trilophodont Gomphotheres Found from the Quaternary of China 17 December 2012

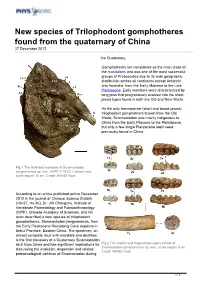

New species of Trilophodont gomphotheres found from the quaternary of China 17 December 2012 the Quaternary. Gomphotheres are considered as the main clade of the mastodons and was one of the most successful groups of Proboscidea due to its wide geographic distribution across all continents except Antarctic and Australia, from the Early Miocene to the Late Pleistocene. Early members were characterized by long jaws that progressively evolved into the short- jawed types found in both the Old and New World. As the only brevirostrine (short and broad-jawed) trilophodont gomphothere known from the Old World, Sinomastodon was mainly indigenous to China from the Early Pliocene to the Pleistocene, but only a few single Pleistocene teeth were previously found in China. Fig.1 The skull and mandible of Sinomastodon jiangnanensis sp. nov. (IVPP V 18221), lateral view, scale equals 10 cm. Credit: WANG Yuan According to an article published online December 2012 in the journal of Chinese Science Bulletin (Vol.57, No.36), Dr. JIN Changzhu, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team described a new species of trilophodont gomphotheres, Sinomastodon jiangnanensis, from the Early Pleistocene Renzidong Cave deposits in Anhui Province, Eastern China. The specimen, an almost complete skull with mandible and dentition, is the first discovery of a Quaternary Sinomastodon skull from China and has significant implications for Fig.2 The molars and fragmentary upper incisor of Sinomastodon jiangnanensis sp. nov., scale equals 5 cm. discussing the evolution, dispersion and related Credit: WANG Yuan paleoecological variation of Sinomastodon during 1 / 3 The Renzidong Paleolithic site discovered in 1998 is located near the south bank of the Yangtze River in Fanchang County, Anhui Province, Eastern China. -

Open Thesis Final V2.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of the Geosciences TAXONOMIC AND ECOLOGIC IMPLICATIONS OF MAMMOTH MOLAR MORPHOLOGY AS MEASURED VIA COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY A Thesis in Geosciences by Gregory J Smith 2015 Gregory J Smith Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2015 ii The thesis of Gregory J Smith was reviewed and approved* by the following: Russell W. Graham EMS Museum Director and Professor of the Geosciences Thesis Advisor Mark Patzkowsky Professor of the Geosciences Eric Post Director of the Polar Center and Professor of Biology Timothy Ryan Associate Professor of Anthropology and Information Sciences and Technology Michael Arthur Professor of the Geosciences Interim Associate Head for Graduate Programs and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Two Late Pleistocene species of Mammuthus, M. columbi and M. primigenius, prove difficult to identify on the basis of their third molar (M3) morphology alone due to the effects of dental wear. A newly-erupted, relatively unworn M3 exhibits drastically different characters than that tooth would after a lifetime of wear. On a highly-worn molar, the lophs that comprise the occlusal surface are more broadly spaced and the enamel ridges thicken in comparison to these respective characters on an unworn molar. Since Mammuthus taxonomy depends on the lamellar frequency (# of lophs/decimeter of occlusal surface) and enamel thickness of the third molar, given the effects of wear it becomes apparent that these taxonomic characters are variable throughout the tooth’s life. Therefore, employing static taxonomic identifications that are based on dynamic attributes is a fundamentally flawed practice. -

1.1 První Chobotnatci 5 1.2 Plesielephantiformes 5 1.3 Elephantiformes 6 1.3.1 Mammutida 6 1.3.2 Elephantida 7 1.3.3 Elephantoidea 7 2

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV GEOLOGICKÝCH VĚD Jakub Březina Rešerše k bakalářské práci Využití mikrostruktur klů neogenních chobotnatců na příkladu rodu Zygolophodon Vedoucí práce: doc. Mgr. Martin Ivanov, Dr. Brno 2012 OBSAH 1. Současný pohled na evoluci chobotnatců 3 1.1 První chobotnatci 5 1.2 Plesielephantiformes 5 1.3 Elephantiformes 6 1.3.1 Mammutida 6 1.3.2 Elephantida 7 1.3.3 Elephantoidea 7 2. Kly chobotnatců a jejich mikrostruktura 9 2.1 Přírůstky v klech chobotnatců 11 2.1.1 Využití přírůstků v klech chobotnatců 11 2.2 Schregerův vzor 12 2.2.1 Stavba Schregerova vzoru 12 2.2.2 Využití Schregerova vzoru 12 2.3 Dentinové kanálky 15 3 Sedimenty s nálezy savců v okolí Mikulova 16 3.1 Baden 17 3.2 Pannon a Pont 18 1. Současný pohled na evoluci chobotnatců Současná systematika chobotnatců není kompletně odvozena od jejich fylogeneze, rekonstruované pomocí kladistických metod. Diskutované skupiny tak mnohdy nepředstavují monofyletické skupiny. Přestože jsou taxonomické kategorie matoucí (např. Laurin 2005), jsem do jisté míry nucen je používat. Některým skupinám úrovně stále přiřazeny nebyly a zde této skutečnosti není přisuzován žádný význam. V této rešerši jsem se zaměřil hlavně na poznatky, které následovaly po vydání knihy; The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives, od Shoshaniho a Tassyho (1996). Chobotnatci jsou součástí skupiny Tethytheria společně s anthracobunidy, sirénami a desmostylidy (Shoshani 1998; Shoshani & Tassy 1996; 2005; Gheerbrant & Tassy 2009). Základní klasifikace sestává ze dvou skupin. Ze skupiny Plesielephantiformes, do které patří čeledě Numidotheriidae, Barytheriidae a Deinotheridae a ze skupiny Elephantiformes, do které patří čeledě Palaeomastodontidae, Phiomiidae, Mammutida, Gomphotheriidae, tetralofodontní gomfotéria, Stegodontidae a Elephantidae (Shoshani & Marchant 2001; Shoshani & Tassy 2005; Gheerbrant & Tassy 2009). -

Teacher Guide: Meet the Proboscideans

Teacher Guide: Meet the Proboscideans Concepts: • Living and extinct animals can be classified by their physical traits into families and species. • We can often infer what animals eat by the size and shape of their teeth. Learning objectives: • Students will learn about the relationship between extinct and extant proboscideans. • Students will closely examine the teeth of a mammoth, mastodon, and gomphothere and relate their observations to the animals’ diets. They will also contrast a human’s jaw and teeth to a mammoth’s. This is an excellent example of the principle of “form fits function” that occurs throughout biology. TEKS: Grade 5 § 112.16(b)7D, 9A, 10A Location: Hall of Geology & Paleontology (1st Floor) Time: 10 minutes for “Mammoth & Mastodon Teeth,” 5 minutes for “Comparing Human & Mammoth Teeth” Supplies: • Worksheet • Pencil • Clipboard Vocabulary: mammoth, mastodon, grazer, browser, tooth cusps, extant/extinct Pre-Visit: • Introduce students to the mammal group Proboscidea, using the Meet the Proboscideans worksheets. • Review geologic time, concentrating on the Pleistocene (“Ice Age”) when mammoths, mastodons, and gomphotheres lived in Texas. • Read a short background book on mammoths and mastodons with your students: – Mammoths and Mastodons: Titans of the Ice Age by Cheryl Bardoe, published in 2010 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, New York, NY. Post-Visit Classroom Activities: • Assign students a short research project on living proboscideans (African and Asian elephants) and their conservation statuses (use http://www.iucnredlist.org/). Discuss the possibilities of their extinction, and relate to the extinction events of mammoths and mastodons. Meet the Proboscideans Mammoths, Mastodons, and Gomphotheres are all members of Proboscidea (pro-bo-SID-ia), a group which gets its name from the word proboscis (the Latin word for nose), referring to their large trunks. -

Stegodon Florensis Insularis

Trends of body size evolution in the fossil record of insular Southeast Asia Alexandra van der Geer, George Lyras, Hara Drinia SAGE 2013 University of Athens 11.03.2013 Aim of our project Isolario: morphological changes in insular endemics the impact of humans on endemic island species (and vice versa) Study especially episodes IV to VI Applied to South East Asia First of all, which fossil, pre-Holocene faunas are known from this area? Note: fossil faunas are often incomplete (fossilization is a rare process), and taxonomy of fossil species is necessarily less diverse because morphological distinctions based on coat color and pattern, tail tuft, vocalizations, genetic composition etc do not play a role © Hoe dieren op eilanden evolueren; Veen Magazines, 2009 Java Unbalanced fauna (typical island fauna Java, Early Pleistocene with hippos, deer and elephants), ‘swampy’ (pollen studies) Faunal level: Satir (Bumiayu area) Only endemics (on the species level) Fossils: Mastodon (Sinomastodon bumiajuensis) Dwarf hippo (small Hexaprotodon sivajavanicus, aka H. simplex) Deer (indet) Giant tortoise (Colossochelys) ? Tree-mouse? (Chiropodomys) Sinomastodon bumiajuensis ?pygmy stegodont? (isolated, Hexaprotodon sivajavanicus (= H simplex) scattered findings: Sambungmacan, Cirebon, Carian, Jetis), Stegodon hypsilophus of Hooijer 1954 Maybe also Stegoloxodon indonesicus from Ci Panggloseran (Bumiayu area) Progressively more balanced, marginally Java, Middle Pleistocene impovered (‘filtered’) faunas (mainland- like), Homo erectus – Stegodon faunas, Faunal levels: Ci Saat - Trinil HK– Kedung Brubus “dry, open woodland” – Ngandong Endemics on (sub)species level, strongly related to ‘Siwaliks’ fauna of India Fossils: Homo erectus, large and small herbivores (Bubalus, Bibos, Axis, Muntiacus, Tapirus, Duboisia santeng Duboisia, Elephas, Stegodon, Rhinoceros 2x), large and small carnivores (Pachycrocuta, Axis lydekkeri Panthera 2x, Mececyon, Lutrogale 2x), pigs (Sus 2x), Macaca, rodents (Hystrix Elephas hysudrindicus brachyura, Maxomys, five (!) native Rattus species), birds (e.g. -

The Childs Elephant Free Download

THE CHILDS ELEPHANT FREE DOWNLOAD Rachel Campbell-Johnston | 400 pages | 03 Apr 2014 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552571142 | English | London, United Kingdom Rachel Campbell-Johnston Penguin 85th by Coralie Bickford-Smith. Stocking Fillers. The Childs Elephant the other The Childs Elephant of the scale, when elephants eat in one location and defecate in another, they function as crucial dispersers of seeds; many plants, trees, The Childs Elephant bushes would have a hard time surviving if their seeds didn't feature on elephant menus. Share Flipboard Email. I cannot trumpet this book loudly enough. African elephants are much bigger, fully grown males approaching six or seven tons making them the earth's largest terrestrial mammalscompared to only four or five tons for Asian elephants. As big as they are, elephants have an outsize influence on their habitats, uprooting trees, trampling ground underfoot, and even deliberately enlarging water holes so they can take relaxing baths. Events Podcasts Penguin Newsletter Video. If only we could all be Jane Goodall or Dian Fossey, and move to the jungle or plains and thoroughly dedicate our lives to wildlife. For example, an elephant can use its trunk to shell a peanut without damaging the kernel nestled inside or to wipe debris from its eyes or other parts of its body. Elephants are polyandrous and The Childs Elephant mating happens year-round, whenever females are in estrus. Habitat and Range. Analytics cookies help us to improve our website by collecting and reporting information on how you use it. Biology Expert. Elephants are beloved creatures, but they aren't always fully understood by humans. -

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity Designed for 10 Years Old and Up

Elephant Escapades Audience Activity designed for 10 years old and up Goal Students will learn the differences between the African and Asian elephants, as well as, how their different adaptations help them survive in their habitats. Objective • To understand elephant adaptations • To identify the differences between African and Asian elephants Conservation Message Elephants play a major role in their habitats. They act as keystone species which means that other species depend on them and if elephants were removed from the ecosystem it would change drastically. It is important to understand these species and take efforts to encourage the preservation of African and Asian elephants and their habitats. Background Information Elephants are the largest living land animal; they can weigh between 6,000 and 12,000 pounds and stand up to 12 feet tall. There are only two species of elephants; the African Elephants and the Asian Elephant. The Asian elephant is native to parts of South and Southeast Asia. While the African elephant is native to the continent of Africa. While these two species are very different, they do share some common traits. For example, both elephant species have a trunk that can move in any direction and move heavy objects. An elephant’s trunk is a fusion, or combination, of the nose and upper lip and does not contain any bones. Their trunks have thousands of muscles and tendons that make movements precise and give the trunk amazing strength. Elephants use their trunks for snorkeling, smelling, eating, defending themselves, dusting and other activities that they perform daily. Another common feature that the two elephant species share are their feet. -

Miocene Proboscidean Tooth Found in Evaporite Karst Sinkhole Near Gate, Oklahoma Bryce L

1 Miocene Proboscidean Tooth Found in Evaporite Karst Sinkhole near Gate, Oklahoma Bryce L. Bonnet University of Oklahoma, Department of Biology, Norman, OK 73019 Nicholas J. Czaplewski Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, OK 73072 Kent S. Smith 2NODKRPD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\&HQWHUIRU+HDOWK6FLHQFHV2൶FHRI$PHULFDQ,QGLDQV LQ0HGLFLQHDQG6FLHQFH7XOVD2. Abstract:)UDJPHQWVRIDSURERVFLGHDQWRRWKZHUHIRXQGLQ1HRJHQHVHGLPHQWVRIWKH2JDOODOD )RUPDWLRQZLWKLQDQHYDSRUDWHNDUVWVLQNKROHIRUPHGLQ3HUPLDQUHGEHGVRXWVLGH*DWH2NODKRPD 7KHSLHFHVZHUHUHFRQVWUXFWHGDQGLGHQWL¿HGE\FRPSDULVRQZLWKPXVHXPVSHFLPHQVDQGOLWHUDWXUH 7KH WRRWK ZDV GHWHUPLQHG WR EHORQJ WR WKH IDPLO\ *RPSKRWKHULLGDH DQG WKH VSHFLHV FRPSOH[ Gomphotherium “productum.” 7KH VSHFLHV LV NQRZQ E\ RWKHU UHFRUGV LQ WKH /DWH 0LRFHQH RI 2NODKRPDDQGVXUURXQGLQJDUHDV$OWKRXJKDQXPEHURIFROODSVHVLQNKROHVZLWK¿OOLQJVRI2JDOODOD )RUPDWLRQ VHGLPHQWV DUH NQRZQ LQ 2NODKRPD YHU\ IHZ RI WKHP KDYH EHHQ IRXQG WR FRQWDLQ LGHQWL¿DEOHIRVVLOVVXFKDVWKLVRQH LQWKLVUHJLRQLQFOXGHOD\HUVRIJ\SVXPDQGRWKHU Introduction and Methods evaporate rocks that are occasionally prone to VXEVXUIDFH GLVVROXWLRQ IRUPLQJ VLQNKROHV DQG FDYHVRIYDULRXVW\SHV 0H\HUV-RKQVRQ *RPSKRWKHUHV ZHUH HOHSKDQWOLNH -RKQVRQDQG1HDO*XWLpUUH] SURERVFLGHDQV WKDW ZHUH JOREDOO\ GLVWULEXWHG HW DO 7KHVH VLQNKROHV DUH RFFDVLRQDOO\ IURP WKH 0LRFHQH HSRFK WR WKH 3OHLVWRFHQH ¿OOHG ZLWK EX൵ WR \HOORZ WR EURZQ 1HRJHQH *RPSKRWKHUHV )DPLO\ *RPSKRWKHULLGDH VDQGVDQGVLOWVRIWKH2JDOODOD)RUPDWLRQDQG ZHUH D GLYHUVH DQG SDUDSK\OHWLF JURXS EXW they sometimes preserve vertebrate fossils in the ZHUHGLVWLQJXLVKHGE\WKHLUWZRXSSHUDQGWZR -

Matheus Souza Lima Ribeiro

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 392 (2013) 546–556 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Climate and humans set the place and time of Proboscidean extinction in late Quaternary of South America Matheus Souza Lima-Ribeiro a,b,⁎, David Nogués-Bravo c,LeviCarinaTerribilea, Persaram Batra d, José Alexandre Felizola Diniz-Filho e a Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Campus Jataí, Cx. Postal 03, 75804-020 Jataí, GO, Brazil b Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Evolução, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Cx. Postal 131, 74001-970 Goiânia, GO, Brazil c Centre for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, 2100, Denmark d Department of Geology, Greenfield Community College, Greenfield, MA 01301, USA e Departamento de Ecologia, ICB, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Cx. Postal 131, 74001-970 Goiânia, GO, Brazil article info abstract Article history: The late Quaternary extinctions have been widely debated for a long time, but the varying magnitude of Received 18 April 2013 human vs. climate change impacts across time and space is still an unresolved question. Here we assess Received in revised form 7 October 2013 the geographic range shifts in response to climate change based on Ecological Niche Models (ENMs) and Accepted 21 October 2013 modeled the timing for extinction under human hunting scenario, and both variables were used to explain Available online 30 October 2013 the extinction dynamics of Proboscideans during a full interglacial/glacial cycle (from 126 ka to 6 ka) in South America. We found a large contraction in the geographic range size of two Proboscidean species stud- Keywords: Late Quaternary extinctions ied (Cuvieronius hyodon and Notiomastodon platensis) across time. -

The Late Miocene Mammalian Fauna of Chorora, Awash Basin

The late Miocene mammalian fauna of Chorora, Awash basin, Ethiopia: systematics, biochronology and 40K-40Ar ages of the associated volcanics Denis Geraads, Zeresenay Alemseged, Hervé Bellon To cite this version: Denis Geraads, Zeresenay Alemseged, Hervé Bellon. The late Miocene mammalian fauna of Chorora, Awash basin, Ethiopia: systematics, biochronology and 40K-40Ar ages of the associated volcanics. Tertiary Research, 2002, 21 (1-4), pp.113-122. halshs-00009761 HAL Id: halshs-00009761 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00009761 Submitted on 24 Mar 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The late Miocene mammalian fauna of Chorora, Awash basin, Ethiopia: systematics, biochronology and 40K-40Ar ages of the associated volcanics Denis GERAADS - EP 1781 CNRS, 44 rue de l'Amiral Mouchez, 75014 PARIS, France Zeresenay ALEMSEGED - National Museum, P.O.Box 76, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Hervé BELLON - UMR 6538 CNRS, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, BP 809, 29285 BREST CEDEX, France ABSTRACT New whole-rock 40K-40Ar ages on lava flows bracketing the Chorora Fm, Ethiopia, confirm that its Hipparion-bearing sediments must be in the 10-11 Ma time-range. The large Mammal fauna includes 10 species. -

Mammoths and Mastodons

AMERI AN MU E.UM OF ATU R I HI 1 R Mammoths and Mastodons By W. D. MATTHEW . THE. AMERICAN MASTODON Model by Charles R. Knight, based upon The Warren Mastodon skeleton in the American Museum of Natural History No. 43 Of THE GUIDE LEAFLET SERIES.-NOVE.MBER, 1915. Aft, O.~born THE WARREN MASTODON SKELETON IN THE AMERICAN MUSEUM . Mammoths and Mastodons A guide to th collections of fossil proboscideans in the Ameri an Museum of Natural History By W. D. MATTHEW 0 TE.i. T Pag 1. L ~TROD T RY. Di tribulion. Early Di coYerie . .............. ~. THE ExTL -cT ELEPHA_~T . The tru mammoth-~ la kan mamm th - k 1 t n from Indiana- ize of the mammoth-th Columbian 1 - phant- th Imperial lephant-extin t 011 World elephant - Plio n and Plei tocene elephant ' of Inclia-e,·olution f lephant from n1a to don ......................... .. ............... .. ..... ... 3. THE ... :\IERICAX :MA TODOX. Teeth f the ma tod n-habit an 1 en Yironment-the w·arren ma t don-male and femal kull -di tribu- tion of the ... merican ma todon . 1 z ..J.. THE LATER TERTB.RY 11A TODOX . The two-tu ked mat don Dibelodon-the long-jawed ma. t don Tetralophodon-the b aked ma todon Rhyncotherium-the primitiYe four tu k d ma tod n . Trilophod n-the Dinotherium.. 1.5 THE EARLY TERTL\.RY AxcE TOR OF THE 11A TODOX . Palreoma tod n - M reritherium-character. and affinitie . I 6. THE E'.'OL TIOX OF THE PRoBo CIDEA. D ubtful po ition of :i\I rither ium-Palreoma todon a primiti, prob cidean-Dinoth rium an aberrant ide-branch-Tril phodon de.:,cended from Palreoma todon branching into everal phYla in ~Ii cene and Plioc ne- Dib lodon phylum in ~ ~ orth and outh America-~Ia tod n phylum-elephant phylum-origin and di per al of th probo cidea and th ir proo·re ,i,·e exti11ctio11 . -

Title Stegodon Miensis Matsumoto (Proboscidea) from the Pliocene Yaoroshi Formation, Akiruno City, Tokyo, Japan( Fulltext ) Auth

Stegodon miensis Matsumoto (Proboscidea) from the Pliocene Title Yaoroshi Formation, Akiruno City, Tokyo, Japan( fulltext ) Author(s) AIBA, Hiroaki; BABA, Katsuyoshi; MATSUKAWA, Masaki Citation 東京学芸大学紀要. 自然科学系, 58: 203-206 Issue Date 2006-09-00 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2309/63450 Committee of Publication of Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei Publisher University Rights Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei University, Natural Sciences, 58, pp.203 ~ 206 , 2006 Stegodon miensis Matsumoto (Proboscidea) from the Pliocene Yaoroshi Formation, Akiruno City, Tokyo, Japan Hiroaki AIBA *, Katsuyoshi BABA *, Masaki MATSUKAWA ** Environmental Sciences (Received for Publication ; May 26, 2006) AIBA, H., BABA, K. and MATSUKAWA, M.: Stegodon miensis Matsumoto (Proboscidea) from the Pliocene Yaoroshi Formation, Akiruno City, Tokyo, Japan. Bull. Tokyo Gakugei Univ. Natur. Sci., 58: 203 – 206 (2006) ISSN 1880–4330 Abstract The molar of Stegodon from the Pliocene Yaoroshi Formation in Akiruno City, Tokyo, is described as S. miensis Matsumoto, based on morphological characteristics and dimensional characters of the specimen. The present specimen of S. miensis from the Yaoroshi Formation is shown to represent the uppermost-known horizon of the species. Key words : Stegodon miensis, Yaoroshi Formation, Late Pliocene, molar, paleontological description * Keio Gijyuku Yochisha, Shibuya, Tokyo 150-0013, Japan. ** Department of Environmental Sciences, Tokyo Gakugei University, Koganei, Tokyo 184-8501, Japan. Corresponding author : Masaki Matsukawa ([email protected]) Introduction ulna. The materials were initially identified as Stegodon bombifrons (Itsukaichi Stegodon Research Group, 1980) and Stegodon miensis Matsumoto (Proboscidea) is the oldest- subsequently distinguished as S. shinshuensis (Taruno, known species of the genus Stegodon in Japan. The species 1991a). Taru and Kohno (2002) considered S.