Insular Dwarfism in Canids on Java (Indonesia) and Its Implication for the Environment of Homo Erectus During the Early and Earl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Species of Trilophodont Gomphotheres Found from the Quaternary of China 17 December 2012

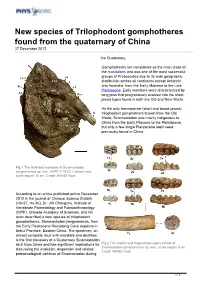

New species of Trilophodont gomphotheres found from the quaternary of China 17 December 2012 the Quaternary. Gomphotheres are considered as the main clade of the mastodons and was one of the most successful groups of Proboscidea due to its wide geographic distribution across all continents except Antarctic and Australia, from the Early Miocene to the Late Pleistocene. Early members were characterized by long jaws that progressively evolved into the short- jawed types found in both the Old and New World. As the only brevirostrine (short and broad-jawed) trilophodont gomphothere known from the Old World, Sinomastodon was mainly indigenous to China from the Early Pliocene to the Pleistocene, but only a few single Pleistocene teeth were previously found in China. Fig.1 The skull and mandible of Sinomastodon jiangnanensis sp. nov. (IVPP V 18221), lateral view, scale equals 10 cm. Credit: WANG Yuan According to an article published online December 2012 in the journal of Chinese Science Bulletin (Vol.57, No.36), Dr. JIN Changzhu, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team described a new species of trilophodont gomphotheres, Sinomastodon jiangnanensis, from the Early Pleistocene Renzidong Cave deposits in Anhui Province, Eastern China. The specimen, an almost complete skull with mandible and dentition, is the first discovery of a Quaternary Sinomastodon skull from China and has significant implications for Fig.2 The molars and fragmentary upper incisor of Sinomastodon jiangnanensis sp. nov., scale equals 5 cm. discussing the evolution, dispersion and related Credit: WANG Yuan paleoecological variation of Sinomastodon during 1 / 3 The Renzidong Paleolithic site discovered in 1998 is located near the south bank of the Yangtze River in Fanchang County, Anhui Province, Eastern China. -

The Island Rule Explains Consistent Patterns of Body Size 2 Evolution Across Terrestrial Vertebrates 3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.114835; this version posted September 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The island rule explains consistent patterns of body size 2 evolution across terrestrial vertebrates 3 4 Ana Benítez-López1,2*, Luca Santini1,3, Juan Gallego-Zamorano1, Borja Milá4, Patrick 5 Walkden5, Mark A.J. Huijbregts1,†, Joseph A. Tobias5,† 6 7 1Department of Environmental Science, Institute for Wetland and Water Research, Radboud 8 University, P.O. Box 9010, NL-6500 GL, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. 9 2Integrative Ecology Group, Estación Biológica de Doñana, CSIC, 41092, Sevilla, Spain 10 3National Research Council, Institute of Research on Terrestrial Ecosystems (CNR-IRET), Via 11 Salaria km 29.300, 00015, Monterotondo (Rome), Italy 12 4Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), 13 Madrid 28006, Spain 14 5Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park, Buckhurst Road, Ascot, 15 Berkshire SL5 7PY, United Kingdom 16 *Correspondence to: [email protected]; [email protected] 17 †These two authors contributed equally 18 19 20 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.114835; this version posted September 17, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

1.1 První Chobotnatci 5 1.2 Plesielephantiformes 5 1.3 Elephantiformes 6 1.3.1 Mammutida 6 1.3.2 Elephantida 7 1.3.3 Elephantoidea 7 2

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV GEOLOGICKÝCH VĚD Jakub Březina Rešerše k bakalářské práci Využití mikrostruktur klů neogenních chobotnatců na příkladu rodu Zygolophodon Vedoucí práce: doc. Mgr. Martin Ivanov, Dr. Brno 2012 OBSAH 1. Současný pohled na evoluci chobotnatců 3 1.1 První chobotnatci 5 1.2 Plesielephantiformes 5 1.3 Elephantiformes 6 1.3.1 Mammutida 6 1.3.2 Elephantida 7 1.3.3 Elephantoidea 7 2. Kly chobotnatců a jejich mikrostruktura 9 2.1 Přírůstky v klech chobotnatců 11 2.1.1 Využití přírůstků v klech chobotnatců 11 2.2 Schregerův vzor 12 2.2.1 Stavba Schregerova vzoru 12 2.2.2 Využití Schregerova vzoru 12 2.3 Dentinové kanálky 15 3 Sedimenty s nálezy savců v okolí Mikulova 16 3.1 Baden 17 3.2 Pannon a Pont 18 1. Současný pohled na evoluci chobotnatců Současná systematika chobotnatců není kompletně odvozena od jejich fylogeneze, rekonstruované pomocí kladistických metod. Diskutované skupiny tak mnohdy nepředstavují monofyletické skupiny. Přestože jsou taxonomické kategorie matoucí (např. Laurin 2005), jsem do jisté míry nucen je používat. Některým skupinám úrovně stále přiřazeny nebyly a zde této skutečnosti není přisuzován žádný význam. V této rešerši jsem se zaměřil hlavně na poznatky, které následovaly po vydání knihy; The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives, od Shoshaniho a Tassyho (1996). Chobotnatci jsou součástí skupiny Tethytheria společně s anthracobunidy, sirénami a desmostylidy (Shoshani 1998; Shoshani & Tassy 1996; 2005; Gheerbrant & Tassy 2009). Základní klasifikace sestává ze dvou skupin. Ze skupiny Plesielephantiformes, do které patří čeledě Numidotheriidae, Barytheriidae a Deinotheridae a ze skupiny Elephantiformes, do které patří čeledě Palaeomastodontidae, Phiomiidae, Mammutida, Gomphotheriidae, tetralofodontní gomfotéria, Stegodontidae a Elephantidae (Shoshani & Marchant 2001; Shoshani & Tassy 2005; Gheerbrant & Tassy 2009). -

Dome-Headed, Small-Brained Island Mammal from the Late Cretaceous of Romania

Dome-headed, small-brained island mammal from the Late Cretaceous of Romania Zoltán Csiki-Savaa,1, Mátyás Vremirb, Jin Mengc, Stephen L. Brusatted, and Mark A. Norellc aLaboratory of Paleontology, Faculty of Geology and Geophysics, University of Bucharest, 010041 Bucharest, Romania; bDepartment of Natural Sciences, Transylvanian Museum Society, 400009 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; cDivision of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024; and dSchool of GeoSciences, Grant Institute, University of Edinburgh, EH9 3FE Edinburgh, United Kingdom Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved March 26, 2018 (received for review January 20, 2018) The island effect is a well-known evolutionary phenomenon, in describe the anatomy of kogaionids in detail, include them in a which island-dwelling species isolated in a resource-limited envi- comprehensive phylogenetic analysis, estimate their body sizes, ronment often modify their size, anatomy, and behaviors compared and present a reconstruction of their brain and sense organs. with mainland relatives. This has been well documented in modern This species exhibits several features that we interpret as re- and Cenozoic mammals, but it remains unclear whether older, more lated to its insular habitat, most notably a brain that is sub- primitive Mesozoic mammals responded in similar ways to island stantially reduced in size compared with close relatives and habitats. We describe a reasonably complete and well-preserved skeleton of a kogaionid, an enigmatic radiation of Cretaceous island- mainland contemporaries, demonstrating that some Mesozoic dwelling multituberculate mammals previously represented by frag- mammals were susceptible to the island effect like in more mentary fossils. -

Stegodon Florensis Insularis

Trends of body size evolution in the fossil record of insular Southeast Asia Alexandra van der Geer, George Lyras, Hara Drinia SAGE 2013 University of Athens 11.03.2013 Aim of our project Isolario: morphological changes in insular endemics the impact of humans on endemic island species (and vice versa) Study especially episodes IV to VI Applied to South East Asia First of all, which fossil, pre-Holocene faunas are known from this area? Note: fossil faunas are often incomplete (fossilization is a rare process), and taxonomy of fossil species is necessarily less diverse because morphological distinctions based on coat color and pattern, tail tuft, vocalizations, genetic composition etc do not play a role © Hoe dieren op eilanden evolueren; Veen Magazines, 2009 Java Unbalanced fauna (typical island fauna Java, Early Pleistocene with hippos, deer and elephants), ‘swampy’ (pollen studies) Faunal level: Satir (Bumiayu area) Only endemics (on the species level) Fossils: Mastodon (Sinomastodon bumiajuensis) Dwarf hippo (small Hexaprotodon sivajavanicus, aka H. simplex) Deer (indet) Giant tortoise (Colossochelys) ? Tree-mouse? (Chiropodomys) Sinomastodon bumiajuensis ?pygmy stegodont? (isolated, Hexaprotodon sivajavanicus (= H simplex) scattered findings: Sambungmacan, Cirebon, Carian, Jetis), Stegodon hypsilophus of Hooijer 1954 Maybe also Stegoloxodon indonesicus from Ci Panggloseran (Bumiayu area) Progressively more balanced, marginally Java, Middle Pleistocene impovered (‘filtered’) faunas (mainland- like), Homo erectus – Stegodon faunas, Faunal levels: Ci Saat - Trinil HK– Kedung Brubus “dry, open woodland” – Ngandong Endemics on (sub)species level, strongly related to ‘Siwaliks’ fauna of India Fossils: Homo erectus, large and small herbivores (Bubalus, Bibos, Axis, Muntiacus, Tapirus, Duboisia santeng Duboisia, Elephas, Stegodon, Rhinoceros 2x), large and small carnivores (Pachycrocuta, Axis lydekkeri Panthera 2x, Mececyon, Lutrogale 2x), pigs (Sus 2x), Macaca, rodents (Hystrix Elephas hysudrindicus brachyura, Maxomys, five (!) native Rattus species), birds (e.g. -

Reconstructing the Late Cretaceous Haţeg Palaeoecosystem

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 293 (2010) 265–270 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Preface An island of dwarfs — Reconstructing the Late Cretaceous Haţeg palaeoecosystem Zoltan Csiki a,⁎, Michael J. Benton b a Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Bucharest, Bd. N. Bălcescu 1, RO-010041 Bucharest, Romania b Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK article info abstract Article history: The Cretaceous was a special time in the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems, and yet the record from Europe Received 3 February 2010 in particular is patchy. This special issue brings together results of multidisciplinary investigations on the Received in revised form 4 May 2010 Late Cretaceous Haţeg area in southwestern Romania, and its continental fossil assemblage, with the aim of Accepted 25 May 2010 exploring an exceptional palaeoecosystem from the European Late Cretaceous. The Haţeg dinosaurs, which Available online 1 June 2010 seem unusually small, have become especially well known as some of the few latest Cretaceous dinosaurs from Europe, comparable with faunas from the south of France and Spain, and preserved at a time when Keywords: Cretaceous most of Europe was under the Chalk Seas. Eastern Europe then, at a time of exceptionally high sea level, was Tetrapods an archipelago of islands, some of them inhabited, but none so extraordinary as Haţeg. If Haţeg truly was an Dinosaurs island (and this is debated), the apparently small dinosaurs might well be dwarfs, as enunciated over Island dwarfing 100 years ago by the colourful Baron Franz Nopcsa, discoverer of the faunas. -

Generality and Antiquity of the Island Rule Mark V

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2013) 40, 1427–1439 SYNTHESIS Of mice and mammoths: generality and antiquity of the island rule Mark V. Lomolino1*, Alexandra A. van der Geer2, George A. Lyras2, Maria Rita Palombo3, Dov F. Sax4 and Roberto Rozzi3 1College of Environmental Science and ABSTRACT Forestry, State University of New York, Aim We assessed the generality of the island rule in a database comprising Syracuse, NY, 13210, USA, 2Netherlands 1593 populations of insular mammals (439 species, including 63 species of fos- Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, The Netherlands, 3Dipartimento di Scienze sil mammals), and tested whether observed patterns differed among taxonomic della Terra, Istituto di Geologia ambientale e and functional groups. Geoingegneria, Universita di Roma ‘La Location Islands world-wide. Sapienza’ and CNR, 00185, Rome, Italy, 4Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Methods We measured museum specimens (fossil mammals) and reviewed = Biology, Brown University, Providence, RI, the literature to compile a database of insular animal body size (Si mean 02912, USA mass of individuals from an insular population divided by that of individuals from an ancestral or mainland population, M). We used linear regressions to investigate the relationship between Si and M, and ANCOVA to compare trends among taxonomic and functional groups. Results Si was significantly and negatively related to the mass of the ancestral or mainland population across all mammals and within all orders of extant mammals analysed, and across palaeo-insular (considered separately) mammals as well. Insular body size was significantly smaller for bats and insectivores than for the other orders studied here, but significantly larger for mammals that utilized aquatic prey than for those restricted to terrestrial prey. -

The Mastodonts of Brazil': the State of the Art of South American

Quaternary International 443 (2017) 52e64 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Sixty years after ‘The mastodonts of Brazil’: The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) * Dimila Mothe a, b, , Leonardo dos Santos Avilla a, c, Lidiane Asevedo a, d, Leon Borges-Silva a, Mariane Rosas e, Rafael Labarca-Encina f, Ricardo Souberlich g, Esteban Soibelzon h, i, Jose Luis Roman-Carrion j, Sergio D. Ríos k, Ascanio D. Rincon l, Gina Cardoso de Oliveira b, Renato Pereira Lopes m a Laboratorio de Mastozoologia, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Bioci^encias, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Pasteur, 458, 501, Urca, CEP 22290-240, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil b Programa de Pos-graduaç ao~ em Geoci^encias, Centro de Tecnologia e Geoci^encias, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Rua Acad^emico Helio Ramos, s/n, Cidade Universitaria, CEP 50740-467, Recife, Brazil c Programa de Pos-graduaç ao~ em Biodiversidade Neotropical, Instituto de Bioci^encias, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Pasteur, 458, 501, Urca, CEP 22290-240, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil d Faculdade de Geoci^encias (Fageo), Campus Cuiaba, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Av. Fernando Correa da Costa, 2367, Jardim Petropolis, CEP 78070-000, Cuiaba, Mato Grosso, Brazil e Laboratorio de Paleontologia, Centro de Ci^encias Agrarias, Ambientais e Biologicas, Universidade Federal do Reconcavo^ da Bahia, Cruz das Almas, Bahia, Brazil f Laboratorio de Paleoecología, Instituto de Ciencias Ambientales y Evolutivas, Universidad Austral de Chile, Casilla 567, Valdivia, Chile g Laboratorio de Paleontología, Departamento de Geología, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Acceso Av. -

Paleobiogeography of Trilophodont Gomphotheres (Mammalia: Proboscidea)

Revista Mexicana deTrilophodont Ciencias Geológicas, gomphotheres. v. 28, Anúm. reconstruction 2, 2011, p. applying235-244 DIVA (Dispersion-Vicariance Analysis) 235 Paleobiogeography of trilophodont gomphotheres (Mammalia: Proboscidea). A reconstruction applying DIVA (Dispersion-Vicariance Analysis) María Teresa Alberdi1,*, José Luis Prado2, Edgardo Ortiz-Jaureguizar3, Paula Posadas3, and Mariano Donato1 1 Departamento de Paleobiología, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006, Madrid, España. 2 INCUAPA, Departamento de Arqueología, Universidad Nacional del Centro, Del Valle 5737, B7400JWI Olavarría, Argentina. 3 LASBE, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque S/Nº, B1900FWA La Plata, Argentina. * [email protected] ABSTRACT The objective of our paper was to analyze the distributional patterns of trilophodont gomphotheres, applying an event-based biogeographic method. We have attempted to interpret the biogeographical history of trilophodont gomphotheres in the context of the geological evolution of the continents they inhabited during the Cenozoic. To reconstruct this biogeographic history we used DIVA 1.1. This application resulted in an exact solution requiring three vicariant events, and 15 dispersal events, most of them (i.e., 14) occurring at terminal taxa. The single dispersal event at an internal node affected the common ancestor to Sinomastodon plus the clade Cuvieronius – Stegomastodon. A vicariant event took place which resulted in two isolated groups: (1) Amebelodontinae (Africa – Europe – Asia) and (2) Gomphotheriinae (North America). The Amebelodontinae clade was split by a second vicariant event into Archaeobelodon (Africa and Europe), and the ancestors of the remaining genera of the clade (Asia). In contrast, the Gomphotheriinae clade evolved mainly in North America. -

Insular Gigantism and Dwarfism in a Snake, Adaptive Response Or

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Nature Precedings 1 Insular gigantism and dwarfism in a snake, adaptive response or spandrel to selection on gape size? Shawn E. Vincent1, Matthew C. Brandley2, Takeo Kuriyama3, Akira Mori4, Anthony Herrel5 & Masami Hasegawa3 1Department of Natural, Information, and Mathematical Sciences, Indiana University Kokomo, Kokomo, IN 46902, USA, 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8105 USA, 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Toho University, Funabashi City, Chiba, 274-8510, Japan, 4Department of Zoology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan, 5UMR 7179 C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., Departement d'Ecologie et de Gestion de la Biodiversite, 57 rue Cuvier, Case postale 55, 75231, Paris Cedex 5, FranceDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8105 USA In biology, spandrels are phenotypic traits that evolve through their underlying developmental, genetic, and/or structural links to another trait under selection1, 2, 3. Despite the importance of the concept of spandrels in biology, empirical examples of spandrels are exceedingly rare at the organismal level2, 3. Here we test whether body size evolution in insular populations of a snake (Elaphe quadrivirgata) is the result of an adaptive response to differences in available prey, or the result of a non- adaptive spandrel resulting from selection on gape size. In contrast to previous hypotheses, Mantel tests show that body size does not coevolve with diet. However, gape size tightly matches diet (birds vs. lizards) across populations, even after controlling for the effects of body size, genetic, and geographic distance. -

Dwarf Elephants on Mediterranean Islands: a Natural Experiment in Parallel Evolution

Dwarf elephants on Mediterranean islands: A natural experiment in parallel evolution Volume 1 of 2 by Victoria Louise Herridge Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment University College London A thesis submitted for the fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London, 2010 1 I, Victoria Louise Herridge, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract Mediterranean dwarf elephants represent some of the most striking examples of phyletic body- size change observed in mammals and are emblematic of the ‘island rule’, where small mammals become larger and large mammals dwarf on islands. The repeated dwarfing of mainland elephant taxa (Palaeoloxodon antiquus and Mammuthus meridionalis) on Mediterranean islands provide a ‘natural experiment’ in parallel evolution, and a unique opportunity to investigate the causes, correlates and mechanisms of island evolution and body-size change. This thesis provides the first pan-Mediterranean study that incorporates taxonomic and allometric approaches to the evolution of dwarf elephants, establishing a framework for the investigation of parallel evolution and key morphological correlates of insular dwarfism. I show that insular dwarfism has evolved independently in Mediterranean elephants at least six times, resulting in at least seven dwarf species. These species group into three, broad size-classes: ‘small- sized’ (P. falconeri, P. cypriotes and M. creticus), ‘medium-sized’ (P. mnaidriensis and P. tiliensis) and ‘large-sized’ (Palaeoloxodon sp. nov. and ‘P. antiquus’ from Crete). Size-shape similarities between independent lineages from the east and central Mediterranean indicate that homoplasy is likely among similar-sized taxa, with implications for the existence of meta-taxa. -

A Grazing Gomphotherium in Middle Miocene Central Asia, 10

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A grazing Gomphotherium in Middle Miocene Central Asia, 10 million years prior to the origin of the Received: 16 November 2017 Accepted: 29 March 2018 Elephantidae Published: xx xx xxxx Yan Wu1,2, Tao Deng1,2,3, Yaowu Hu1,7, Jiao Ma1,7, Xinying Zhou1,2, Limi Mao4, Hanwen Zhang 5,6, Jie Ye1 & Shi-Qi Wang1,2,3 Feeding preference of fossil herbivorous mammals, concerning the coevolution of mammalian and foral ecosystems, has become of key research interest. In this paper, phytoliths in dental calculus from two gomphotheriid proboscideans of the middle Miocene Junggar Basin, Central Asia, have been identifed, suggesting that Gomphotherium connexum was a mixed feeder, while the phytoliths from G. steinheimense indicates grazing preference. This is the earliest-known proboscidean with a predominantly grazing habit. These results are further confrmed by microwear and isotope analyses. Pollen record reveals an open steppic environment with few trees, indicating an early aridity phase in the Asian interior during the Mid-Miocene Climate Optimum, which might urge a diet remodeling of G. steinheimense. Morphological and cladistic analyses show that G. steinheimense comprises the sister taxon of tetralophodont gomphotheres, which were believed to be the general ancestral stock of derived “true elephantids”; whereas G. connexum represents a more conservative lineage in both feeding behavior and tooth morphology, which subsequently became completely extinct. Therefore, grazing by G. steinheimense may have acted as a behavior preadaptive for aridity, and allowing its lineage evolving new morphological features for surviving later in time. This study displays an interesting example of behavioral adaptation prior to morphological modifcation.