Encounters with Post-Communist Sites" 213

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

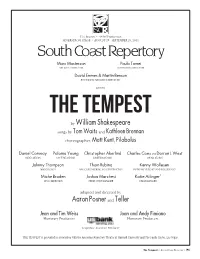

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

November 2016

The Bijou Film Board is a student-run UI org dedicated FilmScene Staff The to American independent, foreign and classic cinema. The Joe Tiefenthaler, Executive Director Bijou assists FilmScene with programming and operations. Andy Brodie, Program Director Andrew Sherburne, Associate Director PictureShow Free Mondays! UI students FREE at the late showing of new release films. Emily Salmonson, Dir. of Operations Family and Children’s Series Ross Meyer, Head Projectionist and Facilities Manager presented by AFTER HOURS A late-night OPEN SCREEN Aaron Holmgren, Shift Supervisor series of cult classics and fan Kate Markham, Operations Assistant favorites. Saturdays at 11pm. The winter return of our ongoing series of big-screen Dec. 4, 7pm // Free admission Dominick Schults, Projection and classics old and new—for movie lovers of all ages! Facilities Assistant FilmScene and the Bijou invite student Abby Thomas, Marketing Assistant Tickets FREE for kids, $5 for adults! Winter films play and community filmmakers to share Saturday at 10am and Thursday at 3:30pm. Wendy DeCora, Britt Fowler, Emma SAT, 11/5 SAT, their work on the big screen. Enter your submission now and get the details: Husar, Ben Johnson, Sara Lettieri, KUBO & THE TWO STRINGS www.icfilmscene.org/open-screen Carol McCarthy, Brad Pollpeter (2016) Dir. Travis Knight. A young THE NEON DEMON (2016) Spencer Williams, Theater Staff boy channels his parents powers. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. An HORIZONS STAMP YOUR PASSPORT Nov. 26 & Dec. 1 aspiring LA model has her Cara Anthony, Felipe Disarz, for a five film cinematic world tour. One UI Tyler Hudson, Jack Tieszen, (1990) Dir. -

Film Studies (FILM) 1

Film Studies (FILM) 1 FILM 252 - History of Documentary Film (4 Hours) FILM STUDIES (FILM) This course critically explores the major aesthetic and intellectual movements and filmmakers in the non-fiction, documentary tradition. FILM 210 - Introduction to Film (4 Hours) The non-fiction classification is indeed a wide one—encompassing An introduction to the study of film that teaches the critical tools educational, experimental formalist filmmaking and the rhetorical necessary for the analysis and interpretation of the medium. Students documentary—but also a rich and unique one, pre-dating the commercial will learn to analyze cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing, sound, and narrative cinema by nearly a decade. In 1894 the Lumiere brothers narration while being exposed to the various perspectives of film criticism in France empowered their camera with a mission to observe and and theory. Through frequent sequence analyses from sample films and record reality, further developed by Robert Flaherty in the US and Dziga the application of different critical approaches, students will learn to Vertov in the USSR in the 1920s. Grounded in a tradition of realism as approach the film medium as an art. opposed to fantasy, the documentary film is endowed with the ability to FILM 215 - Australian Film (4 Hours) challenge and illuminate social issues while capturing real people, places A close study of Australian “New Wave” Cinema, considering a wide range and events. Screenings, lectures, assigned readings; paper required. of post-1970 feature films as cultural artifacts. Among the directors Recommendations: FILM 210, FILM 243, or FILM 253. studied are Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir, Simon Wincer, Gillian Armstrong, FILM 253 - History of American Independent Film (4 Hours) and Jane Campion. -

Lundi 14 Novembre

ÉDITO Alain Rousset, Président du Festival 2015 et 2016 resteront deux années à part pour notre festival. En novembre dernier, suite aux attentats perpétrés avant la 26° édition, nous avons pris la décision de reporter notre manifestation. Ne pas céder sur nos principes : à savoir qu’un lieu de culture, de savoir et de dialogue comme le Festival ne saurait s’éteindre face à la peur. Ainsi, après « Un si Proche-Orient, » c’est le thème « Culture et liberté » qui s’impose comme une réponse fédératrice et constructive au climat anxiogène. Comme un lien emblématique entre les deux éditions de 2016, c’est Chahdortt Djavann, femme de conviction, écrivain française d’origine iranienne, qui nous parlera de culture au pluriel et de liberté à partir de son expérience singulière. Et nous sommes fiers de présenter le film posthume d’Andrezj Wajda qui dans « Afterimage » revient sur les persécutions subies par les artistes de l’autre côté du rideau de fer. De Khomeyni aux djihadistes, de Staline à Hitler, les régimes totalitaires n’ont eu de cesse d’anéantir la culture ou de l’instrumentaliser. Car l’expression artistique est une forme de liberté qui peut remettre en cause un pouvoir politique, religieux ou économique. Le premier enjeu de cette édition est de raconter et d’expliquer comment les artistes, les écrivains ont participé à l’Histoire. Comment, grâce à leur indépendance, à leur génie, ils ont pu éclairer, enchanter leur époque, briser les conformismes. Quelles ont été leurs géniales intuitions, leurs héroïques résistances ou leurs compromissions, leurs aveuglements. Le second enjeu est de montrer comment la culture peut rassembler, éveiller, émerveiller. -

Horaires Des Projections Screening Times

HORAIRES DES PROJECTIONS SCREENING TIMES LE POCKET GUIDE 2016 A ÉTÉ PUBLIÉ AVEC DES INFORMATIONS REÇUES JUSQU'AU 29/04/2016 THE POCKET GUIDE 2016 HAS BEEN EDITED WITH INFORMATION RECEIVED UP UNTIL 29/04/2016 Toutes les projections du Marché sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché du Film ou invitation délivrée par le Service Projections. Les projections dans les salles Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette et Miramar sont accessibles sur présentation du badge Marché ou Festival. Access to Marché du Film screenings is upon presentation of the Marché badge or an invitation given by the Marché Screening Department. Access to screenings taking place in Lumière, Debussy, Buñuel, Salle du Soixantième, Théâtre Croisette and Miramar is upon presentation of either a Marché or Festival badge. CO: Official Competition • HC: Out of Competition • CC: Cannes Classics • CR: Un Certain Regard • BLUE TITLE : Film screened for the first time at a market QR: Directors Fortnight • SC: Semaine de la critique • press: Press allowed • invite only: By invitation only • priority only: Priority badges only SUNDAY 15 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 08:30 (125’) CO 15:30 (158’) CO 19:30 (125’) CO 22:30 (116’) HC LUMIÈRE FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON AMERICAN HONEY FROM THE LAND OF THE MOON THE NICE GUYS TICKET REQUIRED Nicole Garcia Andrea Arnold Nicole Garcia Shane Black 2 294 seats STUDIOCANAL PROTAGONIST PICTURES STUDIOCANAL BLOOM 11:30 (145’) CO 14:30 (162’) CO 17:30 (120’) HC 19:45 (106’) HC SALLE AGASSI, THE -

The Last Samurai. Transcultural Motifs in Jim Jarmusch's Ghost

Adam Uryniak Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland The Last Samurai. Transcultural Motifs in Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai Abstract Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai by - tions of USA, Europe and Japan. Jarmusch’s work can be example of contemporary culture trend named by Wolfgang WelschaJim Jarmusch transculturality. is a film combining According tocinematic his theory tradi the identity of the man is dependent on foreign elements absorbed by the culture in which he lives. Two main inspirations for the director are samurai tradition and bushido code origins of these elements, Jarmush is able to construct a coherent, multi-level narra- tive,on one at thehand, same and time tradition maintaining of gangster distance film ontowards the other. American Despite traditions. the culturally Referencing distant works by transgressive directors (J. P. Melville, Seijun Suzuki) Jarmusch becomes the spokesperson for the genre evolution and its often far-fetched influences. Ghost Dog combines the tradition of American gangster cinema and Japanese samurai (1999) is a collage of various film motifs and traditions. Jarmusch films. The shape of the plot refers to the Blaxploitation cinema, andyakuza direct moviesinspiration, by Seijun expressed Suzuki. by Allspecific this isquotations, spiced up arewith the references gloomy crime to Japanese novels literatureby Jean-Pierre and zen Melville, philosophy. as well In as an brutal interview and withblack Janusz humour-filled Wróblewski di- rector commented on his actions: 138 Adam Uryniak I mix styles up in order to get distance. Not in order to ridicule the hero. And why does the gangster style dominate? I will answer indirectly.. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Jim Jarmusch Regis Dialogue with Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1994

Jim Jarmusch Regis Dialogue with Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1994 Bruce Jenkins: To say that tonight is actually the culmination of about four and a half years worth of conversations, letters, faxes, and the timing has finally been propitious to bring our very special guest. Why we were so interested in Jim is that his work came at, I think, a very important time in the recent history of American narrative filmmaking. I would be one among many who would credit his films with reinvigorating American narrative films, with having really the same impact on filmmaking in this country that John Cassavetes had in a way in the late '50s and early '60s. In coming up with a new cinema that was grounded in the urban experience, in concrete details of the liberality that was much closer to our lives than the films that came out of the commercial studio system. Bruce Jenkins: You'll hear more about Jim Jarmusch from our visiting critic who was here last about three years ago, in connection with the retrospective of William Klein's work. If you have our monograph on Jim Jarmusch, we'll have his writing. It's Jonathan Rosenbaum, who has been our partner in a number of projects here, but most especially our advisor in preparing both the retrospective and dialogue for this evening and the parallel program that plays out on Tuesday evenings, the guilty pleasures and missing influences program, and gives you a little bit of a sense of the context of the work that lead to a really unique sensibility in contemporary filmmaking. -

The Dead Don't Die — They Rise from Their Graves and Savagely Attack and Feast on the Living, and the Citizens of the Town Must Battle for Their Survival

THE DEAD DON’T DIE The Greatest Zombie Cast Ever Disassembled Bill Murray ~ Cliff Robertson Adam Driver ~ Ronnie Peterson Tilda Swinton ~ Zelda Wintson Chloë Sevigny ~ Mindy Morrison Steve Buscemi ~ Farmer Miller Danny Glover ~ Hank Thompson Caleb Landry Jones ~ Bobby Wiggins Rosie Perez ~ Posie Juarez Iggy Pop ~ Coffee Zombie Sara Driver ~ Coffee Zombie RZA ~ Dean Carol Kane ~ Mallory O’Brien Austin Butler ~ Jack Luka Sabbat ~ Zach Selena Gomez ~ Zoe and Tom Waits ~ Hermit Bob The Filmmakers Written and Directed by Jim Jarmusch Produced by Joshua Astrachan Carter Logan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Synopsis . 4 II. “The Dead Don’t Die” Music and Lyrics by Sturgill Simpson 5 III. About the Production . 6 IV. Zombie Apocalypse Now . 8 V. State of the Nation . 11 VI. A Family Affair . 15 VII. Day For Night . 18 VIII. Bringing the Undead to Life . 20 IX. Anatomy of a Scene: Coffee! . 23 X. A Flurry of Zombies . 27 XI. Finding Centerville . 29 XII. Ghosts Inside a Dream . 31 XIII. About the Filmmaker – Jim Jarmusch . 33 XIV. About the Cast . 33 XV. About the Filmmakers . 49 XVI. Credits . 54 2 SYNOPSIS In the sleepy small town of Centerville, something is not quite right. The moon hangs large and low in the sky, the hours of daylight are becoming unpredictable, and animals are beginning to exhibit unusual behaviors. No one quite knows why. News reports are scary and scientists are concerned. But no one foresees the strangest and most dangerous repercussion that will soon start plaguing Centerville: The Dead Don't Die — they rise from their graves and savagely attack and feast on the living, and the citizens of the town must battle for their survival. -

Johnny Stecchino with Roberto Benigni and Nicoletta Braschi Selected Filmography

Johnny Stecchino with Roberto Benigni and Nicoletta Braschi Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Film Works Discussed During the Event Life Is Beautiful (La vita è bella). Dir. Roberto Benigni, 1997, Italy. 116 mins. Production Co.: Cecchi Cori Group Tiger Cinematografica / Melampo Cinematografica. The Monster (Il mostro). Dir. Roberto Benigni, 1994, Italy, France. 112 mins. Production Co.: Canal Plus / IRIS Films / La Sept Cinéma / Melampo Cinematografica / Union Générale Cinématographique. Johnny Stecchino. Dir. Roberto Benigni, 1991, Italy. 102 mins. Production Co.: Cecchi Cori Group Tiger Cinematografica / Penta Film / Silvio Berlusconi Communications. The Little Devil (Il piccolo diavolo). Dir. Roberto Benigni, 1988, Italy. 101 mins. Production Co.: Yarno Cinematografica / Cecchi Gori Group Tiger Cinematografica / Reteitalia. The Great Dictator. Dir. Charles Chaplin, 1940, U.S.A. 125 mins. Production Co.: Charles Chaplin Productions. The Kid. Dir. Charles Chaplin, 1921, U.S.A. 68 mins. Production Co.: Charles Chaplin Productions. Roberto Benigni Filmography To Rome with Love. Dir. Woody Allen, 2012, U.S.A, Italy, Spain. 112 mins. Production Co.: Medusa Film / Gravier Productions / Perdido Productions / Mediapro. Amos Poe’s Divine Comedy (La commedia di Amos Poe). -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Christos Papastergiou Leftover Sites As Disruptors of Urban Narratives In

PEER REVIEW The Leftover City: Leftover Sites as Disruptors of Urban Narratives in the Work of J.G. Ballard, Jim Jarmusch, and Wim Wenders Christos Papastergiou KEYWORDS Leftover City, leftover sites, architecture, urban design, cinema, literature, disruption, narrative, Ballard, Jarmusch, Wenders Leftover City, sitios abandonados, arquitectura, diseño urbano, cine, literatura, narrativa, Ballard, Jarmusch, Wenders Papastergiou, Christos. 2020. “The Leftover City: Leftover Sites as Disruptors of Urban Narratives in the Work of J.G. Ballard, Jim Jarmusch, and Wim Wenders.” informa 13: 208–221. informa Issue #13 ‘Urban Disruptors’ 209 THE LEFTOVER CITY: LEFTOVER SITES AS DISRUPTORS OF URBAN NARRATIVES IN THE WORK OF J.G. BALLARD, JIM JARMUSCH, AND WIM WENDERS Christos Papastergiou ABSTRACT that introduce a creative, holistic understanding of the phenomenon and discusses alternative uses of the During the 1970s and 1980s, emerged a second wave urban environment. The leftover sites can result from of architectural criticism to Modernism related extraordinary conditions; for example, wars, physical with the global oil and fiscal crises of the period. destruction or mass migration. However, they are This criticism, targeting the issues of the ongoing mainly the by-products or the unintended products urbanization, the unlimited spending of resources of long-term processes, such as the fragmentation and the environmental degradation rendered of a city due to rapid, uneven and unbalanced the fragmentation of cities a critical problem for development. They can be produced by the spas- social coherence. In this second period, leftover modic sprawl of the city, inconsistencies in the built sites were rediscovered and appeared as a favorite context and discontinuities of landscape, topography subject in narrative arts.