Jim Jarmusch Regis Dialogue with Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinephilia Or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Elsaesser Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment. In: Marijke de Valck, Malte Hagener (Hg.): Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2005, S. 27– 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 3.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 3.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment Thomas Elsaesser The Meaning and Memory of a Word It is hard to ignore that the word “cinephile” is a French coinage. Used as a noun in English, it designates someone who as easily emanates cachet as pre- tension, of the sort often associated with style items or fashion habits imported from France. As an adjective, however, “cinéphile” describes a state of mind and an emotion that, one the whole, has been seductive to a happy few while proving beneficial to film culture in general. The term “cinephilia,” finally, re- verberates with nostalgia and dedication, with longings and discrimination, and it evokes, at least to my generation, more than a passion for going to the movies, and only a little less than an entire attitude toward life. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments Los Angeles premieres Tues Mar 30 | 8:30 pm $9 [students $7, CalArts $5] Jack H. Skirball Series Known as one of the world’s leading restorationists of experimental and independent cinema, Ross Lipman is also an accomplished filmmaker, writer and performer whose oeuvre has taken on urban decay as a marker of modern consciousness. He visits REDCAT with a program of his own lyrical and speculative works, including the films 10-17-88 (1989, 11 min.) and Rhythm 06 (1994/2008, 9 min.), selections from the video cycle The Perfect Heart of Flux, and the performance essay The Cropping of the Spectacle. “Everything that’s built crumbles in time: buildings, cultures, fortunes, and lives,” says Lipman. “The detritus of civilization tells us no less about our current epoch than an archeological dig speaks to history. The urban ruin is particularly compelling because it speaks of the recent past, and reminds us that our own lives and creations will also soon pass into dust. These film, video, and performance works explore decay in a myriad of forms—architectural, cultural, and personal.” In person: Ross Lipman “Lipman’s films are wonderful…. strong and delicate at the same time… unique. The rhythm and colors are so subtle, deep and soft.” – Nicole Brenez, Cinémathèque Française Program Self-Portrait in Mausoleum DigiBeta, 1 min., 2009 (Los Angeles) Refractions and reflections shot in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery: the half-life of death’s advance. Stained glass invokes the sublime in its filtering of light energy, a pre-cinematic cipher announcing a crack between worlds. -

Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2004 Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Custom Citation King, Homay. "Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces." Camera Obscura 19, no. 2/56 (2004): 105-139, doi: 10.1215/02705346-19-2_56-105. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/40 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Homay King, “Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces,” Camera Obscura 56, v. 19, n. 2 (Summer 2004): 104-135. Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces Homay King How to make the affect echo? — Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes1 1. In the Middle of Things: Opening Night John Cassavetes’ Opening Night (1977) begins not with the curtain going up, but backstage. In the first image we see, Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) has just exited stage left into the wings during a performance of the play The Second Woman. In this play, Myrtle acts the starring role of Virginia, a woman in her early sixties who is trapped in a stagnant second marriage to a photographer. Both Myrtle and Virginia are grappling with age and attempting to come to terms with the choices they have made throughout their lives. -

JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE Fact Sheet

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release August 1992 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE DATES October 30 - November 30, 1992 ORGANIZATION Laurence Kardish, curator, Department of Film, with the collaboration of Mary Lea Bandy, director, Department of Film, and Barbara London, assistant curator, video, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art; and Colin Myles MacCabe, professor of English, University of Pittsburgh, and head of research and information, British Film Institute. CONTENT Jean-Luc Godard, one of modern cinema's most influential artists, is equally important in the development of video. JEAN-LUC GODARD: SON+IMAGE traces the relationship between Godard's films and videos since 1974, from the films Ici et ailleurs (1974) and Numero Deux (1975) to episodes from his video series Histoire(s) du Cinema (1989) and the film Nouvelle Vague (1990). Godard's work is as visually and verbally dense with meaning during this period as it was in his revolutionary films of the 1960s. Using deconstruction and reassemblage in works such as Puissance de la Parole (video, 1988) and Allemagne annee 90 neuf zero (film, 1991), Godard invests the sound/moving image with a fresh aesthetic that is at once mysterious and resonant. Film highlights of the series include Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1979), First Name: Carmen (1983), Hail Mary (1985), Soigne ta droite (1987), and King Lear (1987), among others. Also in the exhibition are Scenario du film Passion (1982), the video essay about the making of the film Passion (1982), which is also included, and the videos he created in collaboration with Anne-Marie Mieville, Soft and Hard (1986) and the series made for television, Six fois deux/Sur et sous la communication (1976). -

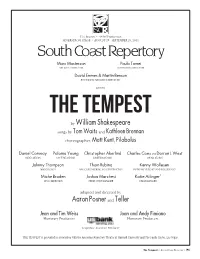

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

November 2016

The Bijou Film Board is a student-run UI org dedicated FilmScene Staff The to American independent, foreign and classic cinema. The Joe Tiefenthaler, Executive Director Bijou assists FilmScene with programming and operations. Andy Brodie, Program Director Andrew Sherburne, Associate Director PictureShow Free Mondays! UI students FREE at the late showing of new release films. Emily Salmonson, Dir. of Operations Family and Children’s Series Ross Meyer, Head Projectionist and Facilities Manager presented by AFTER HOURS A late-night OPEN SCREEN Aaron Holmgren, Shift Supervisor series of cult classics and fan Kate Markham, Operations Assistant favorites. Saturdays at 11pm. The winter return of our ongoing series of big-screen Dec. 4, 7pm // Free admission Dominick Schults, Projection and classics old and new—for movie lovers of all ages! Facilities Assistant FilmScene and the Bijou invite student Abby Thomas, Marketing Assistant Tickets FREE for kids, $5 for adults! Winter films play and community filmmakers to share Saturday at 10am and Thursday at 3:30pm. Wendy DeCora, Britt Fowler, Emma SAT, 11/5 SAT, their work on the big screen. Enter your submission now and get the details: Husar, Ben Johnson, Sara Lettieri, KUBO & THE TWO STRINGS www.icfilmscene.org/open-screen Carol McCarthy, Brad Pollpeter (2016) Dir. Travis Knight. A young THE NEON DEMON (2016) Spencer Williams, Theater Staff boy channels his parents powers. Dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. An HORIZONS STAMP YOUR PASSPORT Nov. 26 & Dec. 1 aspiring LA model has her Cara Anthony, Felipe Disarz, for a five film cinematic world tour. One UI Tyler Hudson, Jack Tieszen, (1990) Dir. -

Film Studies (FILM) 1

Film Studies (FILM) 1 FILM 252 - History of Documentary Film (4 Hours) FILM STUDIES (FILM) This course critically explores the major aesthetic and intellectual movements and filmmakers in the non-fiction, documentary tradition. FILM 210 - Introduction to Film (4 Hours) The non-fiction classification is indeed a wide one—encompassing An introduction to the study of film that teaches the critical tools educational, experimental formalist filmmaking and the rhetorical necessary for the analysis and interpretation of the medium. Students documentary—but also a rich and unique one, pre-dating the commercial will learn to analyze cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing, sound, and narrative cinema by nearly a decade. In 1894 the Lumiere brothers narration while being exposed to the various perspectives of film criticism in France empowered their camera with a mission to observe and and theory. Through frequent sequence analyses from sample films and record reality, further developed by Robert Flaherty in the US and Dziga the application of different critical approaches, students will learn to Vertov in the USSR in the 1920s. Grounded in a tradition of realism as approach the film medium as an art. opposed to fantasy, the documentary film is endowed with the ability to FILM 215 - Australian Film (4 Hours) challenge and illuminate social issues while capturing real people, places A close study of Australian “New Wave” Cinema, considering a wide range and events. Screenings, lectures, assigned readings; paper required. of post-1970 feature films as cultural artifacts. Among the directors Recommendations: FILM 210, FILM 243, or FILM 253. studied are Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir, Simon Wincer, Gillian Armstrong, FILM 253 - History of American Independent Film (4 Hours) and Jane Campion. -

Length in Mina. Length in Nins. METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER. (R

Length Length In Mina. In Nins. HOTEL 124 HOW TO MAKE A MONSTER 75 WARNER BROS. (R) March, 1967. Rod Taylor, Catherine AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL. (R) July, 1968. Robert Spaak. Color. Harris, Paul Brinegar. HOTEL PARADISO (P) 100 HOW TO MURDER A RICH UNCLE 80 METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER. (R) November, 1966. Alec Guin- COLUMBIA. (R) January, 1958. Charles Coburn, Migel Patrick ness, Gina Lollobrigida. Color. HOW TO MURDER YOUR WIFE 118 HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES 64 UNITED ARTISTS. (R) February, 1965. Jack Lemmon, Virna UNITED ARTISTS. (R) June, 1959. Peter Cushing. Lisi. Color. HOUND DOG MAN (Cs) 87 HOW TO SAVE A MARRIAGE -AND RUIN YOUR LIFE (P) 108 TWENTIETH CENTURY-FOX. (R) November, 1959. Fabian, COLUMBIA. (R) March, 1968. Dean Martin, Stella Stevens. Carol Lynley. Color. Color. HOUR OF DECISION (Belt.) 74 HOW TO SEDUCE A WOMAN 106 ASTOR. (R) January, 1957. Jeff Morrow, Hazel Court. CINERAMA. (R) January, 1974. Angus Duncan, Angel Tompkins. HOUR OF THE GUN (R) 100 UNITED ARTISTS. (R) October, 1967. James Garner, Jason HOW TO STEAL A MILLION (P) 127 Robards. Color. 20th CENTURY -FOX. (R) August, 1966. Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole. Color. HOUR THE WOLF (Swed.) 88 OF HOW TO SUCCEED IN BUSINESS WITHOUT REALLY TRYING (P) . 119 LOPERT. (R) April, 1968. Liv Ullmann, Max von Sydow. UNITED ARTISTS. (R) March, 1967. Robert Morse, Michele HOURS OF LOVE, THE (Md. English Titles) 89 Lee. Color. CINEMA V. (R) September, 1965. Vgo Tognazzi, Emmanuela HOW TO STUFF A WILD BIKINI 90 Riva. AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL. (R) July, 1965. Annette HOUSE IS NOT A HOME, A 90 Funicello, Dwayne Hickman. -

Lundi 14 Novembre

ÉDITO Alain Rousset, Président du Festival 2015 et 2016 resteront deux années à part pour notre festival. En novembre dernier, suite aux attentats perpétrés avant la 26° édition, nous avons pris la décision de reporter notre manifestation. Ne pas céder sur nos principes : à savoir qu’un lieu de culture, de savoir et de dialogue comme le Festival ne saurait s’éteindre face à la peur. Ainsi, après « Un si Proche-Orient, » c’est le thème « Culture et liberté » qui s’impose comme une réponse fédératrice et constructive au climat anxiogène. Comme un lien emblématique entre les deux éditions de 2016, c’est Chahdortt Djavann, femme de conviction, écrivain française d’origine iranienne, qui nous parlera de culture au pluriel et de liberté à partir de son expérience singulière. Et nous sommes fiers de présenter le film posthume d’Andrezj Wajda qui dans « Afterimage » revient sur les persécutions subies par les artistes de l’autre côté du rideau de fer. De Khomeyni aux djihadistes, de Staline à Hitler, les régimes totalitaires n’ont eu de cesse d’anéantir la culture ou de l’instrumentaliser. Car l’expression artistique est une forme de liberté qui peut remettre en cause un pouvoir politique, religieux ou économique. Le premier enjeu de cette édition est de raconter et d’expliquer comment les artistes, les écrivains ont participé à l’Histoire. Comment, grâce à leur indépendance, à leur génie, ils ont pu éclairer, enchanter leur époque, briser les conformismes. Quelles ont été leurs géniales intuitions, leurs héroïques résistances ou leurs compromissions, leurs aveuglements. Le second enjeu est de montrer comment la culture peut rassembler, éveiller, émerveiller. -

John Cassavetes: at the Limits Of

JOHN CASSAVETES: AT THE LIMITS OF PERFORMANCE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cinema Studies in the University of Canterbury by Luke Towart University of Canterbury 2014 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………....1 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter One: Performative Opposition: A Woman Under the Influence…………………….20 Chapter Two: A New Kind of Acting: Shadows……………………………………………..52 Chapter Three: Documentaries of Performance: Faces……………………………………...90 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………..122 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………...134 Filmography………………………………………………………………………………...141 1 Acknowledgements Thank you to Alan Wright, my primary supervisor, and Mary Wiles, my secondary supervisor, for their guidance whilst writing this thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the central role of performance in three of the films of John Cassavetes. I identify Cassavetes’ unique approach to performance and analyze its development in A Woman Under the Influence (1974), Shadows (1959) and Faces (1968). In order to contextualize and define Cassavetes’ methodology, I compare and contrast each of these films in relation to two other relevant film movements. Cassavetes’ approach was dedicated to creating alternative forms of performative expression in film, yet his films are not solely independent from filmic history and can be read as being a reaction against established filmic structures. His films revolve around autonomous performances that often defy and deconstruct traditional concepts of genre, narrative structure and character. Cassavetes’ films are deeply concerned with their characters’ isolation and inability to communicate with one another, yet refrain from traditional or even abstract constructions of meaning in favour of a focus on spontaneous, unstructured performance of character. Cassavetes was devoted to exploring the details of personal relationships, identity and social interaction.