Objectification As a Device in the Films of Godard and Breillat: Alphaville (1965) And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis. -

Classic French Film Festival 2013

FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series Webster University’s Winifred Moore Auditorium, 470 E. Lockwood Avenue June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30, 2013 www.cinemastlouis.org Less a glass, more a display cabinet. Always Enjoy Responsibly. ©2013 Anheuser-Busch InBev S.A., Stella Artois® Beer, Imported by Import Brands Alliance, St. Louis, MO Brand: Stella Artois Chalice 2.0 Closing Date: 5/15/13 Trim: 7.75" x 10.25" Item #:PSA201310421 QC: CS Bleed: none Job/Order #: 251048 Publication: 2013 Cinema St. Louis Live: 7.25" x 9.75" FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series The Earrings of Madame de... When: June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30 Where: Winifred Moore Auditorium, Webster University’s Webster Hall, 470 E. Lockwood Ave. How much: $12 general admission; $10 for students, Cinema St. Louis members, and Alliance Française members; free for Webster U. students with valid and current photo ID; advance tickets for all shows are available through Brown Paper Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com (search for Classic French) More info: www.cinemastlouis.org, 314-289-4150 The Fifth Annual Classic French Film Festival celebrates St. Four programs feature newly struck 35mm prints: the restora- Louis’ Gallic heritage and France’s cinematic legacy. The fea- tions of “A Man and a Woman” and “Max and the Junkmen,” tured films span the decades from the 1920s through the Jacques Rivette’s “Le Pont du Nord” (available in the U.S. -

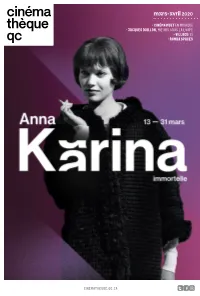

Mars-Avril 2020

mars-avril 2020 · CINÉMA MUET EN MUSIQUE · JACQUES DOILLON, MŒURS SOUS LA LOUPE · VILLAGE(S) · RUMBA SPACES VIVRE SA VIE CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA RENSEIGNEMENTS DROITS D’ENTRÉE 1 HEURES D’OUVERTURE CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA 11 $ / ADULTES BILLETTERIE : ou 514.842.9763 10 $ / AÎNÉ, ÉTUDIANT, ENFANT (5-16 ANS)2 LUNDI AU VENDREDI DÈS 10 h 20 $ / FAMILLE 3 PERSONNES SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DÈS 14 h CINÉMATHÈQUE QUÉBÉCOISE 25 $ / FAMILLE 4 PERSONNES 3 : 335, BOUL. DE MAISONNEUVE EST MEMBRE : 130 $ / 1 AN EXPOSITIONS MONTRÉAL (QUÉBEC) CANADA ABONNEMENT ÉTUDIANT3 : 99 $ / 1 AN LUNDI AU VENDREDI DE 10 h À 21 h H2X 1K1 CENTRE D’ART ET D’ESSAI : SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DE 14 h À 21 h MÉTRO BERRI-UQAM 12 $ / TARIF RÉGULIER MÉDIATHÈQUE GUY-L.-COTÉ : 10 $ / TARIF AINÉ ET ÉTUDIANT MARDI AU VENDREDI DE 9 h 30 À 17 h Imprimé au Québec sur papier québécois 9 $ / TARIF MEMBRE ET ABONNÉ recyclé à 100 % (post-consommation) EXPOSITIONS : ENTRÉE LIBRE ESPACE-CAFÉ-BAR : Distribué par Publicité sauvage 1. Taxes incluses. Le droit d’entrée peut différer dans le cas MERCREDI AU VENDREDI DE 16 h À 21 h de certains programmes spéciaux. 2. Sur présentation d’une carte d’étudiant ou d’identité. La programmation peut être sujette à changement DESIGN : AGENCE CODE 3. Accès illimité à la programmation régulière. sans préavis. Anna Karina immortelle « Tes yeux sont revenus d’un pays arbitraire Où nul n’a jamais su ce que c’est qu’un regard. » Poème de Paul Éluard cité dans Alphaville PIERROT LE FOU DU 13 AU 31 MARS Nous organisons un événement à la mémoire de cette icône majeure, non seulement de la Nouvelle Vague mais aussi du cinéma mondial, qu’a été Anna Karina, disparue le 14 décembre 2019. -

GENEVA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Tous Écrans Programme Revealed!

Press release, under embargo until 11 am Geneva, 12 October 2015 FESTIVAL TOUS éCRANS GENEVA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL GENEVA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL TOUS ÉCRANS PROGRAMME REVEALed! www.tous-ecrans.com The 21st Festival Tous Ecrans returns from 6 to 14 November with an ambitious and entertaining programme including: Swiss premieres of major films by Peter Greenaway, Takeshi Kitano, Jerzy Skolimowski, the Larrieu brothers, Arturo Ripstein, Dibakar Banerjee, Johnnie To, Jay Roach, Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Sarah Gavron; a new section, Rien que pour vos yeux, dedicated to unknown gems unearthed by the Festival’s team; a tribute to Anton Corbijn; the year’s best new TV series and digital virtual reality projects designed to let festivalgoers share in demonstrations against police brutality in New York, or witness first-hand daily life in a Syrian refugee camp. This year’s programme will take you deep into the heart of the audiovisual cosmos with the addition of the Digital Garden – a dome for 360-degree screenings set up in the courtyard of the Pitoëff building – and our already-famous ‘Nuits Blanches’ events with the complicity of artists such as Serge Bozon, Asia Argento and Kid Chocolat, and DJ Cam. The Festival is also expecting a host of guests, including Claire Denis, Ingrid Caven, Anna Karina, Carl Barât, Stuart Staples, the Larrieu brothers, Michael Nouri and Anton Corbijn. Altogether, over 180 celebrities from television, cinema and the digital world have confirmed their attendance. The full programme is available online and the -

Reparto Extraordinario Salas De Cine 2012-2018

1 de 209 Listado de obras audiovisuales Reparto Extraordinario Com. Púb. Salas de Cine 2012 - 2018 Dossier informativo Departamento de Reparto El listado incluye las obras y prestaciones cuyos titulares no hayan sido identificados o localizados al efectuar el reparto, por lo que AISGE recomienda su consulta para proceder a la identificación de tales titulares. 2 de 209 Tipo Código Titulo Tipo Año Protegida Lengua Obra Obra Obra Producción Producción Globalmente Explotación Actoral 725826 ¡¡¡CAVERRRRNÍCOLA!!! Cine 2004 Castellano Actoral 1051717 ¡A GANAR! Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 3609 ¡ATAME! Cine 1989 Castellano Actoral 991437 ¡AVE, CESAR! Cine 2016 Castellano Actoral 19738 ¡AY, CARMELA! Cine 1989 Castellano Actoral 6133 ¡FELIZ NAVIDAD, MISTER LAWRENCE! Cine 1982 Castellano Actoral 964045 ¡QUE EXTRAÑO LLAMARSE FEDERICO! Cine 2013 Castellano Actoral 1051718 ¡QUÉ GUAPA SOY! Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 883562 ¿PARA QUE SIRVE UN OSO? Cine 2011 Castellano Actoral 945650 ¿QUE HACEMOS CON MAISIE? Cine 2012 Castellano Actoral 175 ¿QUE HE HECHO YO PARA MERECER ESTO? Cine 1984 Castellano Actoral 954473 ¿QUE NOS QUEDA? Cine 2012 Castellano Actoral 12681 ¿QUE OCURRIO ENTRE MI PADRE Y TU MADRE? Cine 1972 Castellano Actoral 1051727 ¿QUIÉN ESTÁ MATANDO A LOS MOÑECOS? Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 925329 ¿QUIEN MATO A bAMbI? Cine 2013 Castellano Actoral 801520 ¿QUIEN QUIERE SER MILLONARIO? Cine 2008 Castellano Actoral 12772 ¿QUIEN TEME A VIRGINIA WOOLF? Cine 1966 Castellano Actoral 1020330 ¿TENIA QUE SER EL? Cine 2017 Castellano Actoral 884410 ¿Y -

Curiosities of Superstition

Curiosities of Superstition By W. H. Davenport Adams CURIOSITIES OF SUPERSTITION CHAPTER I. BUDDHISM: ITS ORIGIN AND CEREMONIES. Prayer-Wheels of the Buddhists. TRAVELLING on the borders of Chinese Tartary, in the country of the Lamas or Buddhists, Miss Gordon Cumming remarks that it was strange, every now and again, to meet some respectable-looking workman, twirling little brass cylinders, only about six inches in length, which were incessantly spinning round and round as they walked along the road. What could they be? Not pedometers, not any of the trigonometrical instruments with which the officers of the Ordnance Survey go about armed? No; she was informed that they were prayer-wheels, and that turning them was just about equivalent to the telling of beads, which in Continental lands workmen may often be seen counting as homeward along the road they plod their weary way. The telling of beads seems to the Protestant a superfluous piece of formalism: what then are we to think of prayer by machinery? The prayers, or rather invocations, to Buddha— the Buddhists never pray, in the Christian sense—are all closely written upon strips of cloth or paper; the same sentence being repeated some thousands of times. These strips are placed inside a cylinder, revolving on a long spindle, the end of which is the handle. From the wind-cylinder depends a small lump of metal, which, whirling round, communicates the necessary impetus to the little machine, so that it rotates with the slightest possible effort, and continues to grind any required number of acts of worship, while the owner, with the plaything in his hand, carries on his daily work. -

The Loft Cinema Film Guide

loftcinema.org THE LOFT CINEMA Showtimes: FILM GUIDE 520-795-7777 JANUARY 2020 WWW.LOFTCINEMA.ORG See what films are playing next, buy tickets, look up showtimes & much more! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tamales from Tucson Tamale Company, Burritos from Tumerico, and Ethiopian Wraps JANUARY 2020 from Cafe Desta, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan cookies and more! LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 5 *Pizza served after 5pm daily. NEW FILMS 6-15 35MM SCREENINGS 6 REEL READS SELECTION 12 BEER OF THE MONTH: 70MM SCREENINGS 26, 28 40 HOPPY ANNIVERSARY ALE OSCAR SHORTS 20 SIERRA NEVADA BREWING CO. RED CARPET EVENING 21 ONLY $3.50 WHILE SUPPLIES LAST! SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 22-30 LOFT JR. 24 CLOSED CAPTIONS & AUDIO DESCRIPTIONS! ESSENTIAL CINEMA 25 The Loft Cinema offers Closed Captions and Audio LOFT STAFF SELECTS 29 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our COMMUNITY RENTALS 31-33 website to see which films offer this technology. MONDO MONDAYS 38 CULT CLASSICS 39 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: FREE MEMBERS SCREENING • 1702 Craft Beer & • Epic Cafe • R-Galaxy Pizza 63 UP • Ermanos • Raging Sage (SEE PAGE 8) • aLoft Hotel • Fantasy Comics • Rocco’s Little FRIDAY, JANUARY 10, AT 7:00PM • Antigone Books • First American Title Chicago • Aqua Vita • Frominos • SW University of • Black Crown Visual Arts REGULAR ADMISSION PRICES • Heroes & Villains Coffee • Shot in the Dark $9.75 - Adult | $7.25 - Matinee* • Hotel Congress $8.00 - Student, Teacher, Military • Black Rose Tattoo Cafe • Humanities $6.75 - Senior (65+) or Child (12 & under) • Southern AZ AIDS $6.00 - Loft Members • Bookman’s Seminars Foundation *MATINEE: ANY SCREENING BEFORE 4:00PM • Bookstop • Jewish Community • The Historic Y Tickets are available to purchase online at: • Borderlands Center • Time Market loftcinema.org/showtimes Brewery • KXCI or by calling: 520-795-0844 • Tucson Hop Shop • Brooklyn Pizza • La Indita • UA Media Arts Phone & Web orders are subject to a • Cafe Luce • Maynard’s Market $1 surcharge. -

CHEYNEY, Peter Geboren Als Reginald "Reg" Evelyn Peter Southouse-Cheyney Geboren: Whitechapel, Londen, 22 Februari 1896

CHEYNEY, Peter Geboren als Reginald "Reg" Evelyn Peter Southouse-Cheyney Geboren: Whitechapel, Londen, 22 februari 1896. Overleden: 26 juni 1951 Pseudoniem: Harold Brust Opleiding: advokaat. Carrière: werkte als songwriter, bookmaker, journalist en politicus Militaire dienst: luitenant, British Army; vrijwiller semi-officiële Organisation of the Maintenance of Supplies (OMS). Familie: drie keer getrouwd geweest, o.a. met een danseres (foto: Goodreads.com) website met boekomslagen: http://www.petercheyney.co.uk/Cheyney%20Site/bookshollandcovers.html detective: Lemmuel H. ‘ Lemmy’ Caution , G-man van de F.B.I., cynisch en gewelddadig; Slim Callaghan , privé-detective, Londen; Nick Bellamy , privé-detective; Johnny Vallon , privé-detective, Londen; Michael Kells ; Everard Peter Quayle , spion (" Dark"-serie ), van een top-geheime Britse contra-spionage eenheid, die opereert tegen Nazi-agenten in het Engeland van de Tweede Wereld Oorlog detective: Alonzo MacTavish (kv); Abie Hymie Finkelstein (kv); Etienne MacGregor (kv); Julia Herron (kv); Krasinsky (kv) Lemmy Caution : 1. This Man is Dangerous 1936 Miranda is goedkoper dan U denkt 1957 ZB 65 ook verschenen odt: Deze man is gevaarlijk 1985 ZB 65 2. Poison Ivy 1937 Giftige klimop 1958 ZB 166 eerder verschenen odt: Charlotte is gevaarlijk 1939 Schuyt Fol 21 3. Dames Don't Care 1937 Een vrouw ziet nergens tegenop 1949/61 Br/ZB 422 4. Can Ladies Kill? 1938 Zijn vrouwen moordenaars? 1956/86 ZB 11/ZB 22 5. Don't Get Me Wrong! 1939 Begrijp me niet verkeerd! 1961 ZB 421 6. You'd Be Surprised 1940 Daar sta je van te kijken 1958 ZB 142 7. Your Deal, My Lovely 1941 Jouw beurt, jongedame 1949/60 Bruna/ZB 296 8. -

Documenting the Documentary Grant.Indd 522 10/3/13 10:08 AM Borat 523

Chapter 31 Cultural Learnings of Borat for Make Benefit Glorious Study of Documentary Leshu Torchin Genre designations can reflect cultural understandings of boundaries between perception and reality, or more aptly, distinctions between ac- cepted truths and fictions, or even between right and wrong. Borat: Cul- tural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (Larry Charles, 2006) challenges cultural assumptions by challenging our generic assumptions. The continuing struggle to define the film reflected charged territory of categorization, as if locating the genre would secure the meaning and the implications of Borat. Most efforts to categorize it focused on the humor, referring to it as mockumentary and comedy. But such classifications do not account for how Borat Sagdiyev (Sacha Baron Cohen) interacts with people onscreen or for Baron Cohen’s own claims that these encounters produce significant information about the world. Fictional genres always bear some degree of indexical relationship to the lived world (Sobchack), and that relationship only intensifies in a tradi- tional documentary. Borat, however, confuses these genres: a fictional TV host steps out of the mock travelogue on his fictional hometown and steps into a journey through a real America. The indexical relationship between the screen world and the real world varies, then, with almost every scene, sometimes working as fiction, sometimes as documentary, sometimes as mockumentary. In doing so, the film challenges the cultural assumptions that inhere to expectations of genre, playing with the ways the West (for 13500-Documenting the Documentary_Grant.indd 522 10/3/13 10:08 AM Borat 523 lack of a better shorthand) has mapped the world within the ostensibly rational discourses of nonfiction. -

Portrait: Ulrike Ottinger | Photo: Anne Selders 2010

Ulrike Ottinger grew up in the city of Constance on Lake Constance where she set up her own studio at an early age. From 1962 until the beginning of 1969 she worked as an independent artist in Paris, while learning the technique of etching from Johnny Friedlaender. She also attended lectures given by Claude Lévi-Strauss, Louis Althusser and Pierre Bourdieu at the Collège de France. She exhibited her work at the Biennale internationale de l’estampe, Paris and in various galleries. In the early 70s her interest in painting, photography and performance lead her into making films. Her first film script, ‘The Mongolian Double Drawer’ (Die Mongolische Doppelschublade) was written in 1966. After her return to West Germany she founded, in association with Constance University, the ‘filmclub visuell’ in 1969 in Constance in which international Independent Films, the New German Cinema (Neuer Deutscher Film) and historical films were shown. At the same time she set up the gallery and the edition ‘galeriepress’, in which she presented Wolf Vostell, Allan Kaprow, Fernand Teyssier, Peter Klasen and English pop artists such as R. B. Kitaj, Joe Tilson, Richard Hamilton and David Hockney. Her first film, ‘Laocoon and Sons’ (Laokoon und Söhne), made in collaboration with Tabea Blumenschein, was recorded in 1971-1973 and celebrated its world premiere in the Arsenal Berlin. In 1973 she moved to Berlin and filmed the Happening-documentary ‘Berlinfever – Wolf Vastell’ (Berlinfieber – Wolf Vastell). This was followed by ‘The Enchantment of the Blue Sailors’ (Die Betörung der Blauen Matrosen) in 1975 with Valeska Gert and ‘Madame X – An Absolute Ruler’ (Madame X – Eine absolute Herrscherin) in 1977, co-produced by the ZDF, which caused a great sensation and was an international success.