From the Delta to the Cataract Studies Dedicated to Mohamed El-Bialy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Enigma of KV 55 by Theunis W. Eloff the Valley of the Kings Is A

The Enigma of KV 55 By Theunis W. Eloff The Valley of The Kings is a dry Waddi, or water course, in the hills on the West bank of the Nile at Thebes (Modern Luxor). It is here that most of the kings of the 18th and 19th Dynasties were buried. (c. 1567 – 1200B.C.). The existence of the valley has been known since antiquity and indeed several of the tombs have been open since ancient times. Excavating, or perhaps rather “Treasure Hunting” became popular during the 19th Century and it was only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that more systematic archaeology began to be practised. Concessions to dig in The Valley were granted by the Egyptian Antiquities Department, to only one excavator at a time. In the early 20th Century, this was to Theodore Davis, an elderly, cantankerous American Retired businessman with no knowledge of archaeology, but a desire for “Anticas”. At first, he was prepared to fund exploration but leave matters in the hands of more knowledgeable men like Edward Ayrton and others. Supervision of the excavations fell to the Director of Antiquities for that district, Howard Carter then J. B. Quibell. But, in 1905, the new Inspector of Antiquities, Arthur Weigall, offered Davis a new contract, advising him to employ his own archaeologist and to get involved himself with supervising the work. This proved to be disastrous. He interfered with the work of his excavators and regularly argued with and overruled them. Ayrton complained that he found it difficult to work with the man and when Davis was present work went more slowly, was very unpleasant and things often went wrong. -

Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies B-003〜022

*保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 1 Needle roller and cage assemblies B-003〜022 Needle roller and cage assemblies for connecting rod bearings B-023〜030 Drawn cup needle roller bearings B-031〜054 Machined-ring needle roller bearings B-055〜102 Needle Roller Bearings Machined-ring needle roller bearings, B-103〜120 BEARING TABLES separable Self-aligning needle roller bearings B-121〜126 Inner rings B-127〜144 Clearance-adjustable needle roller bearings B-145〜150 Complex bearings B-151〜172 Cam followers B-173〜217 Roller followers B-218〜240 Thrust roller bearings B-241〜260 Components Needle rollers / Snap rings / Seals B-261〜274 Linear bearings B-275〜294 One-way clutches B-295〜299 Bottom roller bearings for textile machinery Tension pulleys for textile machinery B-300〜308 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 2 B-2 *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 3 Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies *保持器付針状/B001-005_*保持器付針状/B001-005 11/05/24 20:31 ページ 4 Needle roller and cage assemblies NTN Needle Roller and Cage Assemblies This needle roller and cage assembly is one of the or a housing as the direct raceway surface, without using basic components for the needle roller bearing of a inner ring and outer ring. construction wherein the needle rollers are fitted with a The needle rollers are guided by the cage more cage so as not to separate from each other. The use of precisely than the full complement roller type, hence this roller and cage assembly enables to design a enabling high speed running of bearing. -

Emission Station List by County for the Web

Emission Station List By County for the Web Run Date: June 20, 2018 Run Time: 7:24:12 AM Type of test performed OIS County Station Status Station Name Station Address Phone Number Number OBD Tailpipe Visual Dynamometer ADAMS Active 194 Imports Inc B067 680 HANOVER PIKE , LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 X ADAMS Active Bankerts Auto Service L311 3001 HANOVER PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 X ADAMS Active Bankert'S Garage DB27 168 FERN DRIVE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-0420 X ADAMS Active Bell'S Auto Repair Llc DN71 2825 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-4752 X ADAMS Active Biglerville Tire & Auto 5260 301 E YORK ST , BIGLERVILLE PA 17307 -- ADAMS Active Chohany Auto Repr. Sales & Svc EJ73 2782 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-479-5589 X 1489 CRANBERRY RD. , YORK SPRINGS PA ADAMS Active Clines Auto Worx Llc EQ02 717-321-4929 X 17372 611 MAIN STREET REAR , MCSHERRYSTOWN ADAMS Active Dodd'S Garage K149 717-637-1072 X PA 17344 ADAMS Active Gene Latta Ford Inc A809 1565 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1999 X ADAMS Active Greg'S Auto And Truck Repair X994 1935 E BERLIN ROAD , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2926 X ADAMS Active Hanover Nissan EG08 75 W EISENHOWER DR , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-1121 X ADAMS Active Hanover Toyota X536 RT 94-1830 CARLISLE PK , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1818 X ADAMS Active Lawrence Motors Inc N318 1726 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-6664 X 630 HOOVER SCHOOL RD , EAST BERLIN PA ADAMS Active Leas Garage 6722 717-259-0311 X 17316-9571 586 W KING STREET , ABBOTTSTOWN PA ADAMS Active -

Water Quality Assessment Report for United Keno Hill Mines

WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR UNITED KENO HILL MINES Report Prepared for: Elsa Reclamation and Development Company Whitehorse, Yukon Report Prepared by: Minnow Environmental Inc. 2 Lamb Street Georgetown, Ontario L7G 3M9 July 2008 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR UNITED KENO HILL MINES Report Prepared for: Elsa Reclamation and Development Company Whitehorse, Yukon Report Prepared by: Minnow Environmental Inc. Cynthia Russel, B.Sc. Project Manager Patti Orr, M.Sc. Technical Reviewer July 2008 ERDC Water Quality Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY United Keno Hill Mines Limited and UKH Minerals Ltd. were the previous owners of the properties located on and around Galena Hill, Keno Hill, and Sourdough Hill collectively known as the United Keno Hill Mining Property (UKHM). The UKHM is located in north- central Yukon Territory and is comprised of approximately 827 mineral claims covering the three mountains (“hills” named above) over an area of approximately 15,000 ha (about 29 km long and 8 km wide). Associated with the site are abandoned adits, buildings/structures, and waste material which represent a source of contaminants to the downstream watersheds. In June 2005, Alexco Resource Corp was selected as the preferred purchaser of the UKHM assets. Alexco’s subsidiary Elsa Reclamation and Development Company (ERDC) is required to develop a Reclamation Plan for the Existing State of the Mine. As part of the closure planning process, long-term water quality performance will need to be assessed relative to relevant water uses and closure plan options. It is expected that historical sources associated with the UKHM may not allow for generic water quality guidelines to be achieved at all downstream locations and that alternative targets may need to be developed, depending on water use goals. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family Zahi Hawass; Yehia Z. Gad; Somaia Ismail; et al. JAMA. 2010;303(7):638-647 (doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121) Online article and related content current as of October 14, 2010. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638 Supplementary material eSupplement http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/303/7/638/DC1 Correction Contact me if this article is corrected. Citations This article has been cited 7 times. Contact me when this article is cited. Topic collections Neurology; Neurogenetics; Movement Disorders; Rheumatology; Musculoskeletal Syndromes (Chronic Fatigue, Gulf War); Malaria; Genetics; Genetic Disorders; Humanities; History of Medicine; Infectious Diseases Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas. Related Articles published in King Tutankhamun, Modern Medical Science, and the Expanding Boundaries of the same issue Historical Inquiry Howard Markel. JAMA. 2010;303(7):667. Related Letters King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise Eline D. Lorenzen et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. Brenda J. Baker. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2471. James G. Gamble. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Irwin M. Braverman et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2472. Christian Timmann et al. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2473. Subscribe Email Alerts http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts Permissions Reprints/E-prints [email protected] [email protected] http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on October 14, 2010 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family Zahi Hawass, PhD Context The New Kingdom in ancient Egypt, comprising the 18th, 19th, and 20th Yehia Z. -

Il Cristianesimo in Egitto Luci E Ombre in Abydos La Tomba

egittologia.net magazine in questo numero: IL CRISTIANESIMO IN EGITTO EGITTO A VENEZIA LUCI E OMBRE IN ABYDOS SPECIALE NEFERTARI LA TOMBA QV66 AREA ARCHEOLOGICA TEBANA IL VILLAGGIO DI DEIR EL-MEDINA EGITTO IN PILLOLE ISCRIZIONI IERATICHE NELLA TOMBA DI THUTMOSI IV Italiani in Egitto: Ernesto Schiaparelli | L’Arte di Shamira | I papiri di Carla BOLLETTINO INFORMATIVO DELL'ASSOCIAZIONE EGITTOLOGIA.NET NUMERO 3 e d i t o r i a l e La prolungata e precoce presenza di questo Confesso che questo numero di EM – Egitto- insolito e intenso caldo, dà l’impressione che logia.net Magazine è stato sul punto di non l’estate stia già volgendo al termine, anche se uscire! La prossimità con il ferragosto e il in realtà la legna accumulata per l’inverno caldo scoraggiante, soprattutto nelle due set- dovrà aspettare ancora molto tempo prima di timane centrali del mese di luglio – periodo in essere utile. cui il terzo numero del magazine ha comin- Curioso come hanno deciso di chiamare le tre ciato a prendere vita – ci avevano fatto propen- fasi più intense del caldo i meteorologici: Sci- dere per una sospensione, procrastinandone pione, Caronte e Minosse. Curioso perché mi l’uscita direttamente a ottobre. vien da pensare che l’epiteto “Africano” di Sci- Ma abbiamo resistito alla tentazione, sospen- pione e il collegamento con l’Ade che è possi- dendo solo una parte dei temi che abbiamo bile fare con Caronte e Minosse, abbia cominciato a trattare nei numeri precedenti, richiamato alla mente degli scienziati il con- come ci è stato richiesto dagli autori degli cetto di “caldo”. -

Sunflower November 8, 1934

1. Heme'Cominf Htme-coliilf Edition SUNFLOWER Editioi OFFICIAL STUDFNT FVBUCATION OF THE UNtYEKSiTT OF WICHITA XL TWO SECTIONS W IC H IT A . K a n s a s . T h u r s d a y . No v e m b e r s . 1934 SIXTEEN PAGES H«.B vKnrsRsiTT aooKSToas T WeJ onrta pooraAu. snenas ixgta U any Alumni Board Names According to Mra. ifi’akofleld, ep- Barb Candidate For he) 13.1 erator of tlie' Unlvanity of Wien- ita*« Bookulore, there are plain fceted For Staff to Head now Iwing laid to diatribute the W. U. fmitball •tlrkera to ail alu- Home-coming Queen % wceI 'Hantii and all Alumni free of chhrge. wrg e l [imecoming *^35 Yearbook Thli offer la ohiy good during the llnmecomlnr week Aid and !■ vt. SoJ being done to add color to the day Chosen Over Greeks U Fankhouter To Editors PrepaHng To of feitivlty and to advortieo the achool when the old grad* return Wsihl ^ w n Queen At Start Work On to their reapcctive homee. After f Half Time Parnassus thit week end they will be on aale Doris Miller Fort J at a nominal coal. The hook itore alto offert to tha reral now frAturat for Meiiiliep* of the Ifl.'W Parnaa- atuHenta and graduatet of prevloua Chosen Queen F'Ooiiiinn will hrioir him Hill Ktaff. who were choaen by year* Univeraity pennanta and I of irrada back to the cam* the atiideni Hoard of Piibliea- Rag*, table runnera and pillowa to Soturdoy it the opin> thma laic taat week, will aoon match, football pillowa, and ttand covera at a big dltcount. -

Minnowenvironmental Inc

--~------- minnowenvironmental inc. _____ 2 Lamb Street Georgetown, Ontario L7G 3M9 Memorandum To: Dan Cornett, Access Consulting Group From: Cynthia Russel, Minnow Environmental Inc. Date: February 13, 2008-02-13 Re: Update of Surface Water Quality Assessment for United Keno Hill Mine Complex. Minnow Environmental Inc. (Minnow) was retained by Access Consulting Group to undertake an assessment of the existing water quality data for the United Keno Hill Mine Complex (United Keno, Galena and Sourdough Hill). The objective of this assessment was to identify parameters and locations of concern within the downstream waters relative to established guidelines and background. This information, combined with toxicity data and watershed use objectives may then be combined to develop an approach for considering the development of Site Specific Water Quality Objectives (SSWQO) for various parameters and locations. In order to meet the study objectives, a progressive assessment of the available water quality data was undertaken which included the following steps; • Screen all data to identify outliers (i.e., those greater then 3 standard deviations from the mean) and remove these data. • Establish the background concentration for each parameter based the upper limit of background data distribution (mean + t S.D.) for the combined data from KV-1 and KV-37. UKH Surface Water Quality Assessment - Progress Report • Identify parameters with high method detection limits relative to guidelines which preclude determination of whether concentrations exceed the guideline. • Identify background concentrations which exceed the Canadian Water Quality Guidelines (CWQG). • Determine the median, mean, minimum and maximum concentration for each parameter at each location. • Determine which locations exceed background and/or CWQG at measurable (10%) and substantial (50%) frequencies. -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

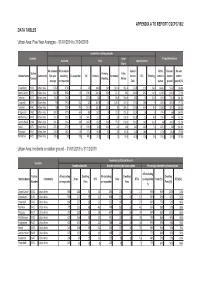

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

Das Wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon Im Internet Pije / Pianchi

Das wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet (WiBiLex) Pije / Pianchi Francis Breyer erstellt: September 2006 Permanenter Link zum Artikel: http://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/stichwort/30976/ Pije / Pianchi Francis Breyer 1. Einleitung Pi(anch)i regierte als zweiter Pharao der kuschitischen 25. Dynastie Ägyptens von 746 bis 715 bzw. 713 v. Chr. (→ Kuschitenzeit). Er war Nachfolger des nubischen Königs Kaschta, der den Machtbereich der Kuschiten erstmals auf ägyptisches Gebiet (Assuan) ausgedehnt und eine ägyptische Titulatur angenommen hatte. Nach dem Ende der ägyptischen Herrschaft über Nubien hatte sich seit dem 10. Jh. v. Chr. ein einheimisches Königreich um den Ǧebel Barkal (Napata) entwickelt, das weiterhin ägyptische Traditionen pegte (Hieroglyphenschrift, Religion). 2. Name Der Name des Pharaos ist in seiner Interpretation und Lesung umstritten (Überblick: Breyer), was damit zusammenhängt, dass Schreibungen mit und solche ohne <‘nch>-Zeichen vorkommen: 1. P3(j)-‘nch.j „Der Lebende“ (Vittmann) [ägyptisch: Artikel p3 + ‘nch „Leben“] 2 . Pije „Der Lebende ist er“ (Priese) [meroitisch pi/pe „Leben“ + „kopulatives / deiktisches Element“ je; ‘nch-Zeichen als Determinativ] 3. <P-j-‘nch> „Herrscher“ (Rilly) [meroitisch b‘(n)che „Herrscher“ o.ä.] In seinen beiden ägyptischen Thonnamen „Mit bleibender Gestalt, ein Re“ (Mn- m‘3.t-R‘[.w]) und „Reich an Maat, ein Re“ (Wsr-m‘3.t-R‘[.w]) lehnt sich Pianchi an Thutmosis III. und Ramses II. an. 3. Familie Die Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse Pi(anch)is (vgl. Lohwasser) sind ebenfalls nicht ganz klar, v.a. weil die Regeln der Thronsukzession bei den Kuschiten nicht bekannt sind (Morkot). Wahrscheinlich war er ein Sohn seines Vorgängers Kaschta und Bruder seines Nachfolgers → Schabaqa, sowie der Amenirdis I., die WiBiLex | Pije / Pianchi 1 er in Theben als Gottesgemahlin des Amun einsetzte (Adoption durch Schepenupet I.). -

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering

Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Yao Zong (Andy) Ng All rights reserved ABSTRACT Expanding the Toolkit for Metabolic Engineering Yao Zong (Andy) Ng The essence of metabolic engineering is the modification of microbes for the overproduction of useful compounds. These cellular factories are increasingly recognized as an environmentally-friendly and cost-effective way to convert inexpensive and renewable feedstocks into products, compared to traditional chemical synthesis from petrochemicals. The products span the spectrum of specialty, fine or bulk chemicals, with uses such as pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, flavors and fragrances, agrochemicals, biofuels and building blocks for other compounds. However, the process of metabolic engineering can be long and expensive, primarily due to technological hurdles, our incomplete understanding of biology, as well as redundancies and limitations built into the natural program of living cells. Combinatorial or directed evolution approaches can enable us to make progress even without a full understanding of the cell, and can also lead to the discovery of new knowledge. This thesis is focused on addressing the technological bottlenecks in the directed evolution cycle, specifically de novo DNA assembly to generate strain libraries and small molecule product screens and selections. In Chapter 1, we begin by examining the origins of the field of metabolic engineering. We review the classic “design–build–test–analyze” (DBTA) metabolic engineering cycle and the different strategies that have been employed to engineer cell metabolism, namely constructive and inverse metabolic engineering.