The 1960S Ian Bannen – Richard Pasco – Tom Courtenay – Richard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

A Devastating Time Bomb Arab Women Turn Trash Into Artistic Works

lifestyle SUNDAY, DECEMBER 27, 2015 Feature This photo provided by Twentieth Century Fox shows, Jennifer Lawrence, from left, Robert De Niro, and Edgar Ramirez, in a scene from the film, “Joy.” Miracle Mops to movie stars: The real Joy dishes on ‘Joy’ o then there was that time that Joy ing. He knows more about me than anybody in Mangano, “Miracle Mop” inventor and the world - I would never need therapy!” Shome shopping entrepreneur, was sitting at a meeting wedged between Jennifer AP: What do you think he found unique Lawrence and Robert De Niro. And De Niro about your story? leaned over and said: “Joy, I have to talk to you. I Mangano: I’ve always had this inner resiliency. I have such a great idea for a product!” grew up in an Italian family in an era where it Mangano continues the story, laughing: was, ‘When are you gonna get married and Arab women turn trash “And Jennifer is on the other side and she says, have children?’ And throughout life, I was ‘Bob, you can’t ask her that. Everybody asks her always taking care of everyone around me. And that!’” She won’t say what the product idea was, through the course of that, I lost ... I think we but allows that when things eventually calm lose what we ARE. And then to find that again, down with the movie, she and Bob will proba- and to go against all odds and have the into artistic works bly get around to discussing it. Late-night courage to keep doing that - I wish everybody meetings with movie stars - oh yes, Bradley could be able to find that space within them- Photo feature by Wassim Haidar Cooper was there, too - isn’t something selves. -

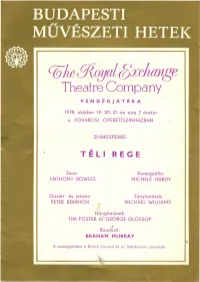

Q;;Heg{Qyalgxchange

q;;he g{qyalgxchange Theatre Company VENDÉGJÁTÉKA 1978. október 19, 20, 21-én este 7 órakor a FŐVÁROSIOPERETTSZíNHÁZBAN SHAKESPEARE: , TELI REGE Zene: Koreográfia: ANTHONY BOWLES MICHELE HARDY Díszlet- és jelmez: Fényhatások: PETER B'ENNION MICHAEL WILLIAMS Hanghatások: TIM FOSTER és GEORGE GLOSSOP ,. Rendező: BRAHAM MURRAY A vendégjátékot a British Council és az Interkoncert szervezte. Szereplők Leontes, Szicília királya James Maxwell MamiIlius, a fia ... Sarah Webb CamilIo Jeffrey Wickham Antigonus Morris Perry szicíliai nemesurak Cliomenes, Peter Guinness Dion Paul Clayton Polixenes, Bohémia királya John Turner Florizel, a fia Richard Durden Archidamus, bohémiai nemesúr Peter Guinness Greg pásztor, akit Perdita atyjának vélnek Harold Goodwin I I Bangó, a fia ... lan Hastings • Autolycus, csavargó Harry Landis Hajós ... Keith Taylor Tömlöcőr Keith Taylor Hermione, Leontes felesége Helen Ryan Perdita, Leontes és Hermione lánya Jacqueline Tong Paulina, Antigonus felesége ... .. Dilys Hamlett Emilia, Hermione udvarhölgye Angela Rooks Philippa Howell Mopsa, Dorcas parasztlányok Chloe Sciennon Knight Moritell, Keith Taylor. Főurak, nemesurak, hölgyek, tisztek, Nicolas Gecks, Peter Guiness szolgák, pásztorok és pásztorlányok Jon Glentoran Történik részint Szicíliában, részínt Bohémiában. , THE ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE COMPANY MANCHESTER A színház jelenlegi társulatának "őse" az az együttes, amely 1959-ben a lan- da ni Lyric Theatre-ben több darabot mutatott be és olyan rendezőkkel, terve- zőkkel és színészekkel büszkélkedett, akik Michel Sein-Denis keze alatt nőttek művésszé és tanultak az Old Vic lsl.olójóbc n. Mindenféle anyagi támogatás nélkül izgalmas előadásokat tudtak teremteni, elsősorban európai drámaírók műveiből, mint Büchner vagy Strindberg. A rnúsornok már csak azért is ~ikere volt, mert Angliában abban az időben nemigen nyúltak az európai klcssziku- sokhoz. A színészeket is igen nagyra értékelte a kritika, többek között Patrick Wym<,rkot, Mai Zetterlinget és Rupert Daviest. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

DICKENS on SCREEN, BFI Southbank's Unprecedented

PRESS RELEASE 12/08 DICKENS ON SCREEN AT BFI SOUTHBANK IN FEBRUARY AND MARCH 2012 DICKENS ON SCREEN, BFI Southbank’s unprecedented retrospective of film and TV adaptations, moves into February and March and continues to explore how the work of one of Britain’s best loved storytellers has been adapted and interpreted for the big and small screens – offering the largest retrospective of Dickens on film and television ever staged. February 7 marks the 200th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ birth and BFI Southbank will host a celebratory evening in partnership with Film London and The British Council featuring the world premiere of Chris Newby’s Dickens in London, the innovative and highly distinctive adaptation of five radio plays by Michael Eaton that incorporates animation, puppetry and contemporary footage, and a Neil Brand score. The day will also feature three newly commissioned short films inspired by the man himself. Further highlights in February include a special presentation of Christine Edzard’s epic film version of Little Dorrit (1988) that will reunite some of the cast and crew members including Derek Jacobi, a complete screening of the rarely seen 1960 BBC production of Barnaby Rudge, as well as day long screenings of the definitive productions of Hard Times (1977) and Martin Chuzzlewit (1994). In addition, there will be the unique opportunity to experience all eight hours of the RSC’s extraordinary 1982 production of Nicholas Nickleby, including a panel discussion with directors Trevor Nunn and John Caird, actor David Threlfall and its adaptor, David Edgar. Saving some of the best for last, the season concludes in March with a beautiful new restoration of the very rare Nordisk version of Our Mutual Friend (1921) and a two-part programme of vintage, American TV adaptations of Dickens - most of which have never been screened in this country before and feature legendary Hollywood stars. -

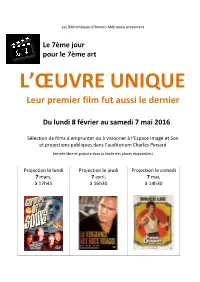

L'œuvre Unique

Les Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole présentent Le 7ème jour pour le 7ème art L’ŒUVRE UNIQUE Leur premier film fut aussi le dernier Du lundi 8 février au samedi 7 mai 2016 Sélection de films à emprunter ou à visionner à l’Espace Image et Son et projections publiques dans l’auditorium Charles Pinsard (entrée libre et gratuite dans la limite des places disponibles) Projection le lundi Projection le jeudi Projection le samedi 7 mars, 7 avril, 7 mai, à 17h45 à 16h30 à 14h30 Un seul film à la réalisation, et puis s'en va... Par envie ou par défi, nombreux sont ceux qui réalisent un premier...et parfois un unique film. Expérience douloureuse, difficultés financières, désintérêt, désir de revenir à son métier d'origine, échec commercial, mort prématurée, raisons politiques, circonstances historiques... Ce ne sont pas les explications qui manquent. Voici quelques exemples connus, d'autres beaucoup moins. Quartet / Dustin Hoffman (2013) Avec Maggie Smith, Tom Courtenay, Billy Connolly… A 76 ans, Dustin Hoffman s'est enfin lancé. L'homme aux deux Oscars, l'acteur à la filmographie éblouissante, est passé derrière la caméra pour raconter l'histoire de quatre anciennes gloires anglaises de l'opéra, retirées dans une maison de retraite pour artiste. Un "Quartet" qui va accepter de rechanter d'une même voix malgré les brouilles du passé, pour sauver l'établissement. Rendez-vous l'été prochain / Philip Seymour Hoffman (2010) Avec Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Ryan, John Ortiz… Découvrir l’unique film de Philip Seymour Hoffman réalisateur, après sa mort, à 46 ans, a quelque chose de troublant. -

Hdnet Movies February 2012 Program Highlights

February 2012 Programming Highlights *All times listed are Eastern Standard Time *Please check the complete Program Schedule or www.hdnetmovies.com for additional films, dates and times HDNet Movies Sneak Previews – Experience exclusive broadcasts of new films before they hit theaters and DVD Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie Premieres Wednesday, 29th at 8:30pm followed by encore presentations at 10:15pm and 12:00am An all new feature film from the twisted minds of cult comedy heroes Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim ("Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job")! Tim and Eric are given a billion dollars to make a movie, but squander every dime... and the sinister Schlaaang corporation is pissed. Their lives at stake, the guys skip town in search of a way to pay the money back. When they happen upon a chance to rehabilitate a bankrupt mall full of vagrants, bizarre stores and a man-eating wolf that stalks the food court, they see dollar signs-a billion of them. Featuring cameos from Awesome Show regulars and some of the biggest names in comedy today! SPOTLIGHT FEATURES – Highlighted feature films airing throughout the month on HDNet Movies See program schedule or www.hdnetmovies.com for additional listings of dates and times Demolition Man – premieres Saturday, February 11th at 7:00pm Starring Sylvester Stallone, Wesley Snipes, Sandra Bullock. Directed by Marco Brambilla Heat – premieres Thursday, February 9th at 8:00pm Starring Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Val Kilmer, Jon Voight. Directed by Michael Mann Mr. Brooks – premieres Thursday, February 2nd at 9:05pm Starring Kevin Costner, Demi Moore, Dane Cook, William Hurt. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

Angus Mackay Diaries Volume III (1966-1977)

Angus Mackay Diaries Volume III (1966-1977) ANGUS MACKAY DIARY NO. 35 Friday July 22 1966 David rang up last night after his first night, about ten to twelve, from the ‘phone-box outside his digs. (The digs are about ¼ of an hours walk, on the way to Walton-on-the-Naze.) He was absolutely miserable. I have never heard him so depressed. As far as we could tell, there was nothing tangible for him to be depressed about, except that he’d felt ‘wooden’, ‘spastic’, ‘the whole company got the laughs’. I’d say this last had something to do with it, as he’d thought himself rather good and better than the others. An audience soon tells one, and the leading girl, whom he hadn’t thought much of ‘came up fantastically.’ That would throw him technically, too. But principally it’s, of course, that it’s all much harder than he expected. As Peter Hoar said he gave a very good period performance, and he’s playing the murderer, not the detective’s assistant, in the next play. I don’t think they’ve lost faith in him yet! (Also, ‘Jane’ is almost certainly by far the better part of the two – Cinderella usually is – and she probably got a lot of the laughs and the praise.) I hope he’ll pick himself up quickly and get on. This will be the testing time, as he has obviously a tendency to give in unless everything is easy for him. So there he is miserable in digs all by himself, about his acting, just as I wanted him to be. -

The English Theatre Studios of Michael Chekhov And

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/57044 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. The English Theatre Studios of Michael Chekhov and Michel Saint-Denis, 1935-1965 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Thomas Cornford, University of Warwick, Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies May 2012 1 Contents List of illustrations........................................................................................... 4 Declaration..................................................................................................... 8 Abstract........................................................................................................... 9 Preface............................................................................................................ 10 Introduction 1 The Theatre Studio in Context........................................ 12 Introduction 2 Chekhov and Saint-Denis in Parallel............................... 28 Section 1 The Chekhov Theatre Studio at Dartington, 1936- 1938............................................................................... -

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Braham Murray

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Braham Murray – interview transcript Interviewer: Adam Smith 5 November 2009 Director. 69 Theatre Company; actors; The Arts Council; Johanna Bryant; Century Theatre; the Lord Chamberlain; choreography; Michael Codron; The Connection; Tom Courtenay; Michael Elliot; Endgame; Lord Gardiner; Hang Down Your Head and Die; Terry Jones; Long Day's Journey into Night; Robert Lindsay; Loot; Oxford University Drama Society (OUDS); Oxford University Experimental Theatre Club (ETC); Mary Rose; Mia Farrow; Michael Meyer; Helen Mirren; musicals; The Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester; set production; She Stoops to Conquer; sound design; David Wood; Casper Wrede; David Wright. AS: This is Adam Smith speaking to Mr Braham Murray on the 5th November 2009. Before we begin can I just thank you on behalf of the University of Sheffield and the British Library Theatre Archive Project for participating. BM: It's a pleasure. AS: Right, so we'll begin at the very beginning. Just before I start, we're looking at 1945 to 1968. BM: Right. AS: But I'll do a bit of background first. BM: OK. AS: Do you remember your first experience of theatre? BM: The very first experience of theatre was pantomime, many many years ago. I can't remember which one. Sorry. AS: That's all right. And, do you recall any of the plays you saw as a young man? http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 20 Theatre Archive Project BM: What do you call young? AS: Adolescent? Teenager? BM: Oh, hundreds! I was stage-struck, and I went to go and see every single play that I could in London within a week of its opening.