The English Theatre Studios of Michael Chekhov And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q;;Heg{Qyalgxchange

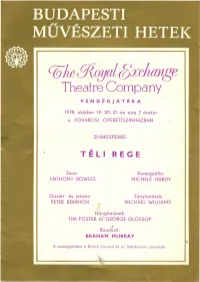

q;;he g{qyalgxchange Theatre Company VENDÉGJÁTÉKA 1978. október 19, 20, 21-én este 7 órakor a FŐVÁROSIOPERETTSZíNHÁZBAN SHAKESPEARE: , TELI REGE Zene: Koreográfia: ANTHONY BOWLES MICHELE HARDY Díszlet- és jelmez: Fényhatások: PETER B'ENNION MICHAEL WILLIAMS Hanghatások: TIM FOSTER és GEORGE GLOSSOP ,. Rendező: BRAHAM MURRAY A vendégjátékot a British Council és az Interkoncert szervezte. Szereplők Leontes, Szicília királya James Maxwell MamiIlius, a fia ... Sarah Webb CamilIo Jeffrey Wickham Antigonus Morris Perry szicíliai nemesurak Cliomenes, Peter Guinness Dion Paul Clayton Polixenes, Bohémia királya John Turner Florizel, a fia Richard Durden Archidamus, bohémiai nemesúr Peter Guinness Greg pásztor, akit Perdita atyjának vélnek Harold Goodwin I I Bangó, a fia ... lan Hastings • Autolycus, csavargó Harry Landis Hajós ... Keith Taylor Tömlöcőr Keith Taylor Hermione, Leontes felesége Helen Ryan Perdita, Leontes és Hermione lánya Jacqueline Tong Paulina, Antigonus felesége ... .. Dilys Hamlett Emilia, Hermione udvarhölgye Angela Rooks Philippa Howell Mopsa, Dorcas parasztlányok Chloe Sciennon Knight Moritell, Keith Taylor. Főurak, nemesurak, hölgyek, tisztek, Nicolas Gecks, Peter Guiness szolgák, pásztorok és pásztorlányok Jon Glentoran Történik részint Szicíliában, részínt Bohémiában. , THE ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE COMPANY MANCHESTER A színház jelenlegi társulatának "őse" az az együttes, amely 1959-ben a lan- da ni Lyric Theatre-ben több darabot mutatott be és olyan rendezőkkel, terve- zőkkel és színészekkel büszkélkedett, akik Michel Sein-Denis keze alatt nőttek művésszé és tanultak az Old Vic lsl.olójóbc n. Mindenféle anyagi támogatás nélkül izgalmas előadásokat tudtak teremteni, elsősorban európai drámaírók műveiből, mint Büchner vagy Strindberg. A rnúsornok már csak azért is ~ikere volt, mert Angliában abban az időben nemigen nyúltak az európai klcssziku- sokhoz. A színészeket is igen nagyra értékelte a kritika, többek között Patrick Wym<,rkot, Mai Zetterlinget és Rupert Daviest. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Frank Grace – Interview Transcript

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Frank Grace – interview transcript Interviewer: Clare Brewer 8 December 2008 Theatre goer. Anna Lucasta; Windsor Rep; The Gioconda Smile; September Tide; The Second Mrs Tanqueray; Oklahoma; Annie Get your Gun; Shakespeare; The Old Vic; Peter Brook; Olivier; Amateur Theatre; Woolford; Look back In Anger; Encore; Theatre Cruelty; Roots; Tis Pity She’s a Whore; A View From the Bridge; Censorship; Theatre Clubs; The Bald Prima Donna; Oh What a Lovely War; Arthur Miller. This transcript has been edited by the interviewee and thus differs in places from the recording. CB: How did you first become interested in theatre? FG: I suppose through [act]ing at school, but in terms of any serious theatre going I suppose it goes back to the late 1940’s... interestingly enough, when I re-looked at the [programmes] that I have got, the first play that I saw [in] the West End was most unusual for the late 1940’s, it was a play called Anna Lucasta,an American play; what was unusual for the 1940s was that it was an all black cast. CB: Really… FG: And it was about a prostitute and my parents took me [laughs] and I think they must have been slightly worried because I was fourteen at the time and it was one of my first experiences. But that was not typical of the first sort of phase of my theatre-going between that moment in 1949 and about 1951 I suppose and [after where] something dramatic begins to happen, I think. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare. Julius Caesar The Shakespeare Ralph Richardson, Anthony SRS Caedmon 3 VG/ Text Recording Society; Quayle, John Mills, Alan Bates, 230 Discs VG+ Howard Sackler, dir. Michael Gwynn Anthony And The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cleopatra Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 235 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Great Scenes The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, TC- Caedmon 1 VG/ Text from Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 1183 Disc VG+ Anthony And Howard Sackler, dir. Cleopatra Titus The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Maxine SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Andronicus Recording Society; Audley, Michael Horden, Colin 227 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Blakely, Charles Gray Pericles The Shakespeare Paul Scofield, Felix Aylmer, Judi SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Dench, Miriam Karlin, Charles 237 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Gray Cymbeline The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Boris Karloff, SRS- Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Pamela Brown, John Fraser, M- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Alan Dobie 236 The Comedy The Shakespeare Alec McCowen, Anna Massey, SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Of Errors Recording Society; Harry H. Corbett, Finlay Currie 205- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. S Venus And The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Max Adrian SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Adonis and A Recording Society; 240 Discs Lover's Howard Sackler, dir. Complaint Troylus And The Shakespeare Diane Cilento, Jeremy Brett, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cressida Recording Society; Cyril Cusack, Max Adrian 234 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. King Richard The Shakespeare John Gielgud, Keith Michell and SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text II Recording Society; Leo McKern 216 Discs Peter Wood, dir. -

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with David Simeon

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk David Simeon – interview transcript Interviewer: Kate Harris 10 November 2006 Actor. Alexandra Theatre, Birmingham; censorship; comedy; drama schools; Cyril Fletcher; John Gielgud; The Guildhall School of Drama; Johnson over Jordan; The Method; John Osborne; pantomime; Harold Pinter; repertory; Derek Salberg; Reggie Salberg; Salisbury theatre; television; Dorothy Tutin; variety. KH: This is an interview on 10th November with David Simeon interviewed by Kate Harris. Can I just confirm that I have got your permission for copyright on this interview? DS: You do indeed, absolutely, yes. KH: That’s great, thank you. I would just like to start by asking you about the beginning of your career, how you became interested in working in the theatre. DS: My first knowledge that I was going to be an actor was when I was round about four years old, and I’ll tell you… My grandmother taught me how to read by the time I was two. OK, not Proust, but I could read by the time I got to infant school. I must tell you this story because it actually has a bearing on what happened later. When I got to infant school I was four and I could, as I said, already read and so I was terribly bored watching people put A, B, C and D up on the blackboard, and by the time I was about five, suddenly this horrible man came into the second form of the infants who turned out to be the headmaster of the primary school opposite and he ordered me out, took me across the road, put me on a dais in front of the whole of the primary school, and I was made to read from the Bible at the age of five. -

August Newsletter 2018 Draft V1.Pages

Belsize Residents Association Newsletter August 2018 Notes from your Chair Contents Welcome to the August Newsletter. Focus on: Royal Central School We had a splendid day for this year’s Garden Party of Speech and Drama - 2 and are grateful to all who helped organised it. The Air Quality Monitoring - 4 venue was fabulous and we had plenty of great BRA and the Planning System - 5 conversation and cakes. Camden Transport Strategy Workshop - 6 Camden Local Transport Meeting - 6 In this issue, we focus on the Royal Central School Trees In Camden- 7 of Speech and Drama. The School’s Deputy Blue Plaques for Belsize- 7 Principal introduces us to this fascinating local Start of Works Delayed at Swiss Cottage - 7 institution. Also, the School is kindly inviting Help Needed - 7 members to an event in the Autumn. Details about Dates for Your Diary - 8 this will follow by email as we’re still organising it. The issue has an article which asks whether you may BRA Autumn Event be able to help with a pollution monitoring initiative Royal Central School of for Camden. As the area has some pollution Speech and Drama hotspots, there is a need for good local data about pollution, and this initiative seeks to fill that gap. BRA continues to monitor planning applications. One of our planning experts describes the hurdles faced by small organisations like us in challenging large planning applications. The summer is likely to BRA has been invited to see see this issue at large, as challenges are mounted Central students perform at the about the developments around Swiss Cottage. -

En Garde 3 50 Cents

EN GARDE 3 50 CENTS ®Z7\ ER ED THREE T-o^yneny "R/cc-er <dc-e R h a magazine of personal opinions, natter and comment - especially about Diana Rigg, Patrick MacNee and THE AVENGERS CONTENTS: TACKING ..........................an editorial .... ,pg.U by ye editor HIOFILE ON DIANA RIGG pg,? by warner bros. IROFIIE ON PATRICK MACNEE •pg.11by warner bros. THE AVENGERS ....... .a review • .......................... pg«l£ by gary crowdus TWO SEASONS - AND A HAIF ... a listing pg ,22 by ye ed TO HONOR HONOR ... .a section for honor, , pg,33 compiled by ed YOU HAVE JUST BEEN MURDERED , ,a review ........................... pg.U8 by rob firebaugh NEWS AND NOTES , , . « • .various tidbits. , • • • • pg .50 by ye editor Front Cover shows a scene from Art Credits; "The Master Minds" , 1966 show. Bacover shows sequence cut out "Walt" • , pages 11 and lb for Yankee audience. R. Schultz . , . pages 3, U, 7, 15, 18, 19,22, 35, E2, and $0 This magazine is irregularly published by: Mr, Richard Schultz, 19159 Helen, Detroit, Michigan, E823E, and: Mr. Gary Crowdus, 27 West 11th street New York City, N.Y., 10011 WELKCMMEN First off, let me apologize for the unfortunate delay in bringing out this third issue* I had already planned to bring this fount of Rigg-oriented enthusiasm out immediately after the production of #2. Like, I got delayed. Some things were added to #3, some were unfortunately dropped, some never arrived, and then I quickly came down with a cold and broke a fingernail* Have you ever tried typing stencils with a broken fingernail? Combined with the usual lethargy, this was, of course, very nearly disastrous* But, here it is* ' I hope you like it. -

The Routledge Companion to Directors' Shakespeare Glen Byam

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare John Russell Brown Glen Byam Shaw Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203932520.ch3 Nick Walton Published online on: 26 Apr 2010 How to cite :- Nick Walton. 26 Apr 2010, Glen Byam Shaw from: The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203932520.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 GLEN BYAM SHAW Nick Walton Glen Byam Shaw’s direction was commonly perceived as being ‘assured and unobtrusive’, ‘blessedly straightforward’, ‘a model of sensitive presentation’, and above all ‘sympathetic to the players and the play’. His direction was also said to possess a ‘Mozartian quality’, ‘a radiance’ and an ‘unobtrusive charm’. -

The 1960S Ian Bannen – Richard Pasco – Tom Courtenay – Richard

The 1960s Ian Bannen – Richard Pasco – Tom Courtenay – Richard Chamberlain Ian Bannen, thought to be the first Scot to play Hamlet, had come to Stratford ten years previously as a walk-on. In Peter Wood’s 1961 production, staged at the re-named Royal Shakespeare Theatre, he was the first actor to play the Prince under Peter Hall’s regime as Director. In his startling and controversial performance the noble mind was gone, as was all trace of Ophelia’s portrait of ‘the glass of fashion and the mould of form’. Several critics were appalled at his lunatic neuroticism, and spelt out the symptoms: ‘His eyes are sometimes wild, staring, and seemingly on fire, his body shakes, and his hands and head tremble feverishly,’ wrote one. Another, who judged him ‘unconditionally mad as a hatter’, explained: ‘This man is mad when we first find him, and the full horror of madness, the almost delicious danger, comes once the revenge motif has been sounded by the Ghost, when a paroxysm of rage and physical excitement sweeps the body, and the psychopathic obsession for vengeance becomes a great and sinister game.’ Bannen explained: ‘I see Hamlet as being in a high state of tension the whole time....He needs something to help him relax the tension. That is why he loves codding Polonius, jazzing it up with the Players, and playing around with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.’ Later he admitted to having over-played the madness. He also confessed he found the part exhausting, because Shakespeare’s mind moved at such enormous speed. -

Thetidesoftime

The Oxford University Doctor Who Society Mag azine TThhee TTiiddeess ooff TTiimmee Issue 29 Easter Vacation 2004 BUFFY AND THE BRITISH Star Trek The Prisoner The career of Brian Clemens … …and something called Doctor Who , apparently. The Tides of Time 29 • 36 • Easter Vacation 2004 The Tides of Time 29 • 1 • Easter Vacation 2004 the difference between people and objects. The Tides of Time Shorelines When Lamia presents Grendel with her android copy of Romana, a primitive device More shorelines IIIIIIIssssssssuuueee 222999 EEEaaasssstttteeerrrr VVVaaaccccaaattttiiiiiiiooonnn 222000000444 By the Editor Well, that’s about it for now. Thank you to everyone intended to kill the Doctor, Grendel exclaims that it is a killing machine, and that he would for getting this far; unless you have started at this Editor Matthew Kilburn end of the magazine, in which case, welcome to Turn of the Tide? marry it. In doing so he discloses his [email protected]@history.oxford.ac.ukoxford.ac.uk This issue of The Tides of Time is being issue 29 of The Tides of Time ! I said a few years ago, published within a few weeks of the understanding of power, that it comprises the when I cancelled my own zine, The Troglodyte , after SubSubSub-Sub ---EditorEditor Alexandra Cameron cancellation of Angel by the WB ability to kill people. Grendel is a powerful one issue, that having got a job as an editor I didn’t Executive Editor Matthew Peacock network in the USA. The situation may man, in his own society, and at least recognises think that editing in my spare time would have much Production Associate Linda Tyrrell have moved on by the time that you the Doctor as another man of power; but the appeal.