Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Braham Murray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q;;Heg{Qyalgxchange

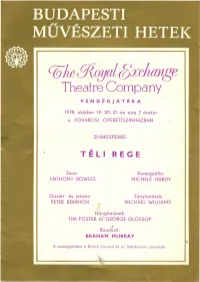

q;;he g{qyalgxchange Theatre Company VENDÉGJÁTÉKA 1978. október 19, 20, 21-én este 7 órakor a FŐVÁROSIOPERETTSZíNHÁZBAN SHAKESPEARE: , TELI REGE Zene: Koreográfia: ANTHONY BOWLES MICHELE HARDY Díszlet- és jelmez: Fényhatások: PETER B'ENNION MICHAEL WILLIAMS Hanghatások: TIM FOSTER és GEORGE GLOSSOP ,. Rendező: BRAHAM MURRAY A vendégjátékot a British Council és az Interkoncert szervezte. Szereplők Leontes, Szicília királya James Maxwell MamiIlius, a fia ... Sarah Webb CamilIo Jeffrey Wickham Antigonus Morris Perry szicíliai nemesurak Cliomenes, Peter Guinness Dion Paul Clayton Polixenes, Bohémia királya John Turner Florizel, a fia Richard Durden Archidamus, bohémiai nemesúr Peter Guinness Greg pásztor, akit Perdita atyjának vélnek Harold Goodwin I I Bangó, a fia ... lan Hastings • Autolycus, csavargó Harry Landis Hajós ... Keith Taylor Tömlöcőr Keith Taylor Hermione, Leontes felesége Helen Ryan Perdita, Leontes és Hermione lánya Jacqueline Tong Paulina, Antigonus felesége ... .. Dilys Hamlett Emilia, Hermione udvarhölgye Angela Rooks Philippa Howell Mopsa, Dorcas parasztlányok Chloe Sciennon Knight Moritell, Keith Taylor. Főurak, nemesurak, hölgyek, tisztek, Nicolas Gecks, Peter Guiness szolgák, pásztorok és pásztorlányok Jon Glentoran Történik részint Szicíliában, részínt Bohémiában. , THE ROYAL EXCHANGE THEATRE COMPANY MANCHESTER A színház jelenlegi társulatának "őse" az az együttes, amely 1959-ben a lan- da ni Lyric Theatre-ben több darabot mutatott be és olyan rendezőkkel, terve- zőkkel és színészekkel büszkélkedett, akik Michel Sein-Denis keze alatt nőttek művésszé és tanultak az Old Vic lsl.olójóbc n. Mindenféle anyagi támogatás nélkül izgalmas előadásokat tudtak teremteni, elsősorban európai drámaírók műveiből, mint Büchner vagy Strindberg. A rnúsornok már csak azért is ~ikere volt, mert Angliában abban az időben nemigen nyúltak az európai klcssziku- sokhoz. A színészeket is igen nagyra értékelte a kritika, többek között Patrick Wym<,rkot, Mai Zetterlinget és Rupert Daviest. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós-Graduação Em Letras/Inglês E Literatura Correspondente

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE SHAKESPEARE IN THE TUBE: THEATRICALIZING VIOLENCE IN BBC’S TITUS ANDRONICUS FILIPE DOS SANTOS AVILA Supervisor: Dr. José Roberto O’Shea Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras/Inglês e Literatura Correspondente da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento parcial dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS FLORIANÓPOLIS MARÇO/2014 Agradecimentos CAPES pelo apoio financeiro, sem o qual este trabalho não teria se desenvolvido. Espero um dia retribuir, de alguma forma, o dinheiro investido no meu desenvolvimento intelectual e profissional. Meu orientador e, principalmente, herói intelectual, professor José Roberto O’Shea, por ter apoiado este projeto desde o primeiro momento e me guiado com sabedoria. My Shakespearean rivals (no sentido elisabetano), Fernando, Alex, Nicole, Andrea e Janaína. Meus colegas do mestrado, em especial Laísa e João Pedro. A companhia de vocês foi de grande valia nesses dois anos. Minha grande amiga Meggie. Sem sua ajuda eu dificilmente teria terminado a graduação (e mantido a sanidade!). Meus professores, especialmente Maria Lúcia Milleo, Daniel Serravalle, Anelise Corseuil e Fabiano Seixas. Fábio Lopes, meu outro herói intelectual. Suas leituras freudianas, chestertonianas e rodrigueanas dos acontecimentos cotidianos (e da novela Avenida Brasil, é claro) me influenciaram muito. Alguns russos que mantém um site altamente ilegal para download de livros. Sem esse recurso eu honestamente não me imaginaria terminando essa dissertação. Meus amigos. Vocês sabem quem são, pois ouviram falar da dissertação mais vezes do que gostariam ao longo desses dois anos. Obrigado pelo apoio e espero que tenham entendido a minha ausência. -

Feature Film Credits______

PAUL D. PATTISON : MAKE UP ARTIST / WIG MAKER MAIN FEATURES PTY LTD cell: 0417 367 103 / email: [email protected] UK.PASSPORT HOLDER ACADEMY AWARD WINNER “BRAVEHEART’ B.A.F.T.A. NOMINEE “BRAVEHEART” EMMY NOMINEE “IKE THUNDER IN JUNE” Member of the ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES PAUL HAS PERSONALLY ATTENDED TO Angelina Jolie, Russell Crowe, Kelly Mcgilles, Nick Nolte, Sir Anthony Hopkins, Jason Scott Lee, Radha Mitchell, Sean Bean Mathew Modine, Judy Davis, Cole Hauser, Clive Owen, Freddie Prince Junior, Pete Postlethwaite, Rowan Atkinson, Tom Selleck, Dougray Scott, Poppy Montgomery, Kirstie Alley, Patrick Dempsey, Anne Margaret, Patrick Stewart, Miranda Otto, Mary Steenburgen, Olivier Martinez, Chris Odonnell, Jackie Chan, Guy Pearce, Jon Voight, Alfred Molina, Sigrid Thornton, Richard Roxborough, Micheal York, Sarah Michelle Gellar, Gregory Peck To Name A Few. FEATURE FILMS Solomon Kane Monkeys Mask Mission Top Secret Dying Breed Mission Impossible II The Nostradamus Kid Blood & Chocolate Nice Guy Wind Silent Hill Dear Walter, Dear Claudia Spotswood Eucalyptus Praise Farewell to the King The Cave The Well The Man from Snowy River 2 Anacondas Doing Time for Patsy Cline The Lighthorseman Red Head- Lucy Ball Story Dead Heart Slate Wynn and Me Loves Brother Braveheart / OSCAR WINNER Ground Zero Beyond Borders Rapa Nui Kangaroo Extreme Team Body Melt Scooby Doo Silver Brumby MINI SERIES Chicane Man from Snowy River (Series 2 & 3) Come Midnight Monday The Company / EMMY nom. Flying Doctors All the Green Year IKE - Eisenhower Story / EMMY nom. Mission Impossible (Series 2) Words Fail Me Blonde - Marilyn Monroe Story All the Way I Can Jump Puddles Farscape Series 2 The Far Country Outbreak of Love Noahs Ark A Thousand Skies Lucinda Brayford Moby Dick Keepers Beverly Hills Family Robinson Home Paul D. -

Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures

Social Education 76(1), pp 22–28 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Reel History of the World: Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures William Benedict Russell III n today’s society, film is a part of popular culture and is relevant to students’ as well as an explanation as to why the everyday lives. Most students spend over 7 hours a day using media (over 50 class will view the film. Ihours a week).1 Nearly 50 percent of students’ media use per day is devoted to Watching the Film. When students videos (film) and television. With the popularity and availability of film, it is natural are watching the film (in its entirety that teachers attempt to engage students with such a relevant medium. In fact, in or selected clips), ensure that they are a recent study of social studies teachers, 100 percent reported using film at least aware of what they should be paying once a month to help teach content.2 In a national study of 327 teachers, 69 percent particular attention to. Pause the film reported that they use some type of film/movie to help teach Holocaust content. to pose a question, provide background, The method of using film and the method of using firsthand accounts were tied for or make a connection with an earlier les- the number one method teachers use to teach Holocaust content.3 Furthermore, a son. Interrupting a showing (at least once) national survey of social studies teachers conducted in 2006, found that 63 percent subtly reminds students that the purpose of eighth-grade teachers reported using some type of video-based activity in the of this classroom activity is not entertain- last social studies class they taught.4 ment, but critical thinking. -

Before-The-Act-Programme.Pdf

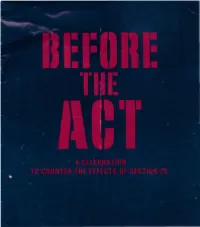

Dea F ·e s. Than o · g here tonight and for your Since Clause 14 (later 27, 28 and 29) was an contribution o e Organisation for Lesbian and Gay nounced, OLGA members throughout the country Action (OLGA) in our fight against Section 28 of the have worked non-stop on action against it. We raised Local Govern en Ac . its public profile by organising the first national Stop OLGA is a a · ~ rganisa ·o ic campaigns The Clause Rally in January and by organising and on iss es~ · g lesbians and gay e . e ber- speaking at meetings all over Britain. We have s ;>e o anyone who shares o r cancer , lobbied Lords and MPs repeatedly and prepared a e e eir sexuality, and our cons i u ion en- briefings for them , for councils, for trade unions, for s es a no one political group can take power. journalists and for the general public. Our tiny make C rre ly. apart from our direct work on Section 28, shift office, staffed entirely by volunteers, has been e ave th ree campaigns - on education , on lesbian inundated with calls and letters requ esting informa cus ody and on violence against lesbians and gay ion and help. More recently, we have also begun to men. offer support to groups prematurely penalised by We are a new organisation, formed in 1987 only local authorities only too anxious to implement the days before backbench MPs proposed what was new law. then Clause 14, outlawing 'promotion' of homosexu The money raised by Before The Act will go into ality by local authorities. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

En Garde 3 50 Cents

EN GARDE 3 50 CENTS ®Z7\ ER ED THREE T-o^yneny "R/cc-er <dc-e R h a magazine of personal opinions, natter and comment - especially about Diana Rigg, Patrick MacNee and THE AVENGERS CONTENTS: TACKING ..........................an editorial .... ,pg.U by ye editor HIOFILE ON DIANA RIGG pg,? by warner bros. IROFIIE ON PATRICK MACNEE •pg.11by warner bros. THE AVENGERS ....... .a review • .......................... pg«l£ by gary crowdus TWO SEASONS - AND A HAIF ... a listing pg ,22 by ye ed TO HONOR HONOR ... .a section for honor, , pg,33 compiled by ed YOU HAVE JUST BEEN MURDERED , ,a review ........................... pg.U8 by rob firebaugh NEWS AND NOTES , , . « • .various tidbits. , • • • • pg .50 by ye editor Front Cover shows a scene from Art Credits; "The Master Minds" , 1966 show. Bacover shows sequence cut out "Walt" • , pages 11 and lb for Yankee audience. R. Schultz . , . pages 3, U, 7, 15, 18, 19,22, 35, E2, and $0 This magazine is irregularly published by: Mr, Richard Schultz, 19159 Helen, Detroit, Michigan, E823E, and: Mr. Gary Crowdus, 27 West 11th street New York City, N.Y., 10011 WELKCMMEN First off, let me apologize for the unfortunate delay in bringing out this third issue* I had already planned to bring this fount of Rigg-oriented enthusiasm out immediately after the production of #2. Like, I got delayed. Some things were added to #3, some were unfortunately dropped, some never arrived, and then I quickly came down with a cold and broke a fingernail* Have you ever tried typing stencils with a broken fingernail? Combined with the usual lethargy, this was, of course, very nearly disastrous* But, here it is* ' I hope you like it. -

Vivat Regina! Melbourne Celebrates the Maj’S 125Th Birthday

ON STAGE The Spring 2011 newsletter of Vol.12 No.4 Vivat Regina! Melbourne celebrates The Maj’s 125th birthday. he merriment of the audience was entrepreneur Jules François de Sales — now, of course, Her Majesty’s — almost continuous throughout.’ Joubert on the corner of Exhibition and celebrated its birthday by hosting the third TThat was the observation of the Little Bourke Streets. The theatre’s début Rob Guest Endowment Concert. The Rob reporter from M elbourne’s The Argus who was on Friday, 1 October 1886. Almost Guest Endowment, administered by ANZ ‘covered the very first performance in what exactly 125 years later — on Monday, Trustees, was established to commemorate was then the Alexandra Theatre, the 10 October 2011 the merriment was one of Australia’s finest music theatre handsome new playhouse built for similarly almost continuous as the theatre performers, who died in October 2008. * The Award aims to build and maintain a This year’s winner was Blake Bowden. Mascetti, Barry Kitcher, Moffatt Oxenbould, appropriate time and with due fuss and ‘“Vivat Regina!” may be a bit “over the Clockwise from left: Shooting the community for upcoming music theatre He received a $10 000 talent development the theatre’s archivist Mary Murphy, and publicity, as well as the final casting, but I top” — but then, why not?’ commemorative film in The Maj's foyer. Mike Walsh is at stairs (centre). artists and to provide one night every year grant, a media training session, a new theatre historian Frank Van Straten. am thrilled that they are spearheaded by a Why not, indeed! when all facets of the industry join to headshot package and a guest performance Premier Ted Baillieu added a special brand new production of A Chorus Line — as Rob Guest Endowment winner Blake Bowden welcome a new generation of performers. -

The 1960S Ian Bannen – Richard Pasco – Tom Courtenay – Richard

The 1960s Ian Bannen – Richard Pasco – Tom Courtenay – Richard Chamberlain Ian Bannen, thought to be the first Scot to play Hamlet, had come to Stratford ten years previously as a walk-on. In Peter Wood’s 1961 production, staged at the re-named Royal Shakespeare Theatre, he was the first actor to play the Prince under Peter Hall’s regime as Director. In his startling and controversial performance the noble mind was gone, as was all trace of Ophelia’s portrait of ‘the glass of fashion and the mould of form’. Several critics were appalled at his lunatic neuroticism, and spelt out the symptoms: ‘His eyes are sometimes wild, staring, and seemingly on fire, his body shakes, and his hands and head tremble feverishly,’ wrote one. Another, who judged him ‘unconditionally mad as a hatter’, explained: ‘This man is mad when we first find him, and the full horror of madness, the almost delicious danger, comes once the revenge motif has been sounded by the Ghost, when a paroxysm of rage and physical excitement sweeps the body, and the psychopathic obsession for vengeance becomes a great and sinister game.’ Bannen explained: ‘I see Hamlet as being in a high state of tension the whole time....He needs something to help him relax the tension. That is why he loves codding Polonius, jazzing it up with the Players, and playing around with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.’ Later he admitted to having over-played the madness. He also confessed he found the part exhausting, because Shakespeare’s mind moved at such enormous speed.