Herrick, Lott R 1933-1937

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Friendly Endeavor, September 1937

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Friendly Endeavor (Quakers) 9-1937 Friendly Endeavor, September 1937 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_endeavor Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Friendly Endeavor, September 1937" (1937). Friendly Endeavor. 186. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_endeavor/186 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Friendly Endeavor by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ) ( THE FRIENDLY ENDEAVOR JOURNAL. FOR FRIENDS IN THE NORTHWEST Volume 16, No. 9 PORTLAND, OREGON September, 1937 NEW CHART BIDS HIGH IN ALONE H I - L i G H T S O F INTEREST FOR 1937-38 B y PA U L C A M M A C K The new chart entitled "Circling the Globe You admire the one who has grit to do things alone; you like him because he TWIN ROCKS with Christian Endeavor" created much in terest at the semi-armual business meeting first flew the Atlantic and alone. You held during Twin Rocks Conference when admire Jesus because He, though forsaken CONFERENCE presented by Miss Ruth Gulley. of friends and Father, T'his year's chart was revealed to be a trip went alone to bear your around the world visiting enroute our Bolivian contemptible guilt. TOLD missionaries, the Chilsons and Choate in Both man and God Africa, Carrie Wood in India, Esther Gulley will admire you, if you and John and Laura Trachsel in China. -

Federal Reserve Bulletin September 1937

FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 1937 Reduction in Discount Rates Banking Developments in First Half of 1937 Objectives of Monetary Policy Acceptance Practice Statistics of Bank Suspensions BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM CONSTITUTION AVENUE AT 20TH STREET WASHINGTON Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Review of the month—Reduction in discount rates—Banking developments in the first half of 1937 819-826 Objectives of monetary policy 827 National summary of business conditions 829-830 Summary of financial and business statistics 832 Law Department: Regulation M relating to foreign branches of national banks and corporations organized under section 25 (a) of Federal Reserve Act - 833 Rulings of the Board: Reserve requirements of foreign banking corporations 833 Matured bonds and coupons as cash items in process of collection in computing reserves 833 Appointment of alternates for members of trust investment committee of national bank 834 New Federal Reserve building _• 835-838 Acceptance practice 839-850 Condition of all member banks on June 20, 1937 (from Member Bank Call Report No. 73) _. _ 851-852 French financial measures . _. _: 853 Annual report of the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic. _ _ . _ _ _..._. _ 854-865 Bank suspensions, 1921-1936 866-910 Financial, industrial, and commercial statistics, United States: Member bank reserves, Reserve bank credit, and related items 912 Federal Reserve bank statistics 913-917 Reserve position of member -

Panama Canal Record

MHOBiaaaan THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD VOLUME 31 m ii i ii ii bbwwwuu n—ebbs > ii h i 1 1 nmafimunmw Panama Canal Museum Gift ofthe UNIV. OF FL. LIB. - JUL 1 2007 j Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/panamacanalr31193738isth THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD PUBLISHED MONTHLY UNDER THE AUTHORITY AND SUPER- VISION OF THE PANAMA CANAL AUGUST 15, 1937 TO JULY 15, 1938 VOLUME XXXI WITH INDEX THE PANAMA CANAL BALBOA HEIGHTS, CANAL ZONE 1938 THE PANAMA CANAL PRESS MOUNT HOPE, CANAL ZONE 1938 For additional copies of this publication address The Panama Canal, Washington, D.C., or Balboa Heights, Canal Zone. Price of bound volumes, $1.00; for foreign postal delivery, $1.50. Price of current subscription, $0.50 a year, foreign, $1.00. ... .. , .. THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE PANAMA CANAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY Subscription rates, domestic, $0.50 per year; foreign, $1.00; address The Panama Canal Record, Balboa Heights, Canal Zone, or, for United States and foreign distribution, The Panama Canal, Washington, D. C. Entered as second-class matter February 6, 1918, at the Post Office at Cristobal, C. Z., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Certificate— direction of the Governor of The By Panama Canal the matter contained herein is published as statistical information and is required for the proper transaction of the public business. Volume XXXI Balboa Heights, C. Z., August 15, 1937 No. Traffic Through the Panama Canal in July 1937 The total vessels of all kinds transiting the Panama Canal during the month of July 1937, and for the same month in the two preceding years, are shown in the following tabulation: July 1937 July July Atlantic Pacific 1935 1936 to to Total Pacific Atlantic 377 456 257 200 457 T.nnal commerrifl 1 vessels ' 52 38 30 32 62 Noncommercial vessels: 26 26 22 22 44 2 2 1 1 For repairs 2 1 State of New York 1 Total 459 523 310 255 565 1 Vessels under 300 net tons, Panama Canal measurement. -

Annual Report 1937

Third Annual Report of the .~s.Securities and Exchange 1/ Commission _Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1937 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: IlI-3T For sale by the Snperintendent or Documents. Wash1nllton. D. C. • - • - • - - • PrIce 25 cents SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Office: 1778 Pennsylvada Avenue NW. WashUIgton, D. C. COMMISSIONERS WILLIAM O. DOUGLAS, Chairman GEORGE C. MATHEWS ROBERT E. HEALY J. D. Ross FRANCIS P. BRASSOR, Secretary Address All Communications SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D. C. n tI (f ~.!) 8 fc ,USA3 /~'3q CxJfl3 . LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSroNI' ~ashi~on,January3,19S~ Sm: I have the honor to transmit to you the Third .Annual Re- port of the Securities and Exc~e Commission, in compliance with the provisions of Section 23 (b) of the Securities Exchange .Act of 1934, approved June 6, 1934, and Section 23 of the Public Utility Holding Company .Act of 1935, approved .August 26, 1935. Respectfully, WILLIAM O. DOUGLAS, Chairman. The PRESIDENT OF THE SENATE, The SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Washi~on,D. O. m ~"" I t CONTENTS Page Functions of the Commission _ 1 Commissioners and Staff Officers _ 1 Registration of Securities Under the Securities Act of 1933 _ 2 Examination of Securities Act Registration Statements _ 2 Securities Act Forms, Rules and Regulations - _ 7 Statistics of Securities Registered under the Securities Act. _ 9 Statistics of Private Placings . _ 13- Exemption From Registration Requirements of Securities Act _ 14 Exemptions -

'Against the State': a Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937)

Articles 29/4 2/9/99 10:15 am Page 485 Helen Graham ‘Against the State’: A Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937) The state is not something which can be destroyed by a revolution, but is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of human behaviour; we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently.1 For a European audience, one of the most famous images fixing the memory of the Spanish Civil War is of the street fighting- across-the-barricades which occurred in Barcelona between 3 and 7 May 1937. Those days of social protest and rebellion have been represented in many accounts, of which the single best known is still George Orwell’s contemporary diary account, Homage to Catalonia, recently given cinematic form in Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom. It is paradoxical, then, that the May events remain among the least understood in the history of the civil war. The analysis which follows is an attempt to unravel their complexity. On the afternoon of Monday 3 May 1937 a detachment of police attempted to seize control of Barcelona’s central telephone exchange (Telefónica) in order to remove the anarchist militia forces present therein. News of the attempted seizure spread rapidly through the popular neighbourhoods of the old town centre and port. By evening the city was on a war footing, although no organization — inside or outside government — had issued any such command. The next day barricades went up in central Barcelona; there was a generalized work stoppage and armed resistance to the Catalan government’s attempt to occupy the telephone exchange. -

Spanish Civil War 1936–9

CHAPTER 2 Spanish Civil War 1936–9 The Spanish Civil War 1936–9 was a struggle between the forces of the political left and the political right in Spain. The forces of the left were a disparate group led by the socialist Republican government against whom a group of right-wing military rebels and their supporters launched a military uprising in July 1936. This developed into civil war which, like many civil conflicts, quickly acquired an international dimension that was to play a decisive role in the ultimate victory of the right. The victory of the right-wing forces led to the establishment of a military dictatorship in Spain under the leadership of General Franco, which would last until his death in 1975. The following key questions will be addressed in this chapter: + To what extent was the Spanish Civil War caused by long-term social divisions within Spanish society? + To what extent should the Republican governments between 1931 and 1936 be blamed for the failure to prevent civil war? + Why did civil war break out? + Why did the Republican government lose the Spanish Civil War? + To what extent was Spain fundamentally changed by the civil war? 1 The long-term causes of the Spanish Civil War Key question: To what extent was the Spanish Civil War caused by long-term social divisions within Spanish society? KEY TERM The Spanish Civil War began on 17 July 1936 when significant numbers of Spanish Morocco Refers military garrisons throughout Spain and Spanish Morocco, led by senior to the significant proportion of Morocco that was army officers, revolted against the left-wing Republican government. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1937

SEPTEMBER 1937 SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 17 NUMBER 9 A Review of Economic Changes during the elapsed period of 1937 is presented in the article on page 12. The improvement this year has been substantial, but the rate of increase has tended to slacken in recent months. NATIONAL INCOME has been much larger than in 1936 and this further gain in the dollar figures has meant an increase in ''rear' income. This expansion has reflected the sharp rise in labor income, the gain in income from agriculture and other business enterprises, and the rapid rise in dividend payments. CASH FARM INCOME from marketings and Government payments for the full year 1937 is estimated by the Department of Agriculture at $9,000,000,000, an increase of 14 percent over the total for 1936, and the largest income since 1929. Industrial output for the first 8 months was about 15 percent larger than in the corresponding period of 1936. The increase in freight-car loadings was almost as large, while that for retail trade was somewhat less. OTHER FEATURES of the general business situation are sum- marized, and a table provides data on the extent of the gains over 1932 and 1936. A special chart on page 4 affords a quick comparison of six principal economic series for the 1929-37 period. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE ALEXANDER V. DYE, Director SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS Prepared in the DIVISION OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH ROY G. -

THE NAZI PLAN This Is a List of Intertitles As They Appear in Proper Chronological Order

THE NAZI PLAN This is a list of intertitles as they appear in proper chronological order. These digital transfers were made in 2018 from fifteen reels of 35mm nitrate film comprising “The Nazi Plan” located in the International Court of Justice Nuremberg Archives. USHMM Film ID 4303 The Nazi Plan Part I The Rise of the NSDAP 1921-1933 Alfred Rosenberg Describes the Early Nazi Struggles for Power Reichsparteitag Nürnberg 1927 Deutschland erwache! Julius Streicher Auch Die übrigen Führer begrüssen Die Ankommenden Kolonne reicht sich an Kolonne Deutschlands Freiheit wird wiedererstehen, genau so wie Volk und Vaterland wiedererstehen warden. Kraftvoller als je! USHMM Film ID 4304 Herbst 1932 Hitler’s First Speech as Chancellor 30 January 1933 Goering, Named Prussian Minister of Interior by Hitler, Outlines His Program February 1933 Election Day in Bavaria 5 March 1933 Gewerkschafts= haus Election Day in Berlin 5 March 1933 Meeting of Reichstag at which Hitler and His Cabinet Receive Plenary Powers of Legislation 24 March 1933 USHMM Film ID 4305 Part 2 Acquiring Totalitarian Control of Germany 1933-1935 Opening of the Official Anti-Semitic Campaign 1 April 1933 Foreign Press Conference April 1933 The Burning of the Books 10 May 1933 Christening of New Great German Aircraft in Presence of Cabinet Members Reichstag Address on Disarmament 17 May 1933 Youth Meeting in Thuringia 18 June 1933 USHMM Film ID 4306 Swastika becomes National Symbol 9 July 1933 Fifth Party Congress September 1933 Inauguration at Frankfurt am Main of New Section of the Super-Highway Net-work 23 September 1933 1934 Over Radio Net-work Hess Administers Oath of Allegiance to more than One Million Leaders of the NSDAP and all Affiliated Organizations 25 February 1934 Hess Reaffirms Hitler’s Faith in S.A. -

102 BE VIEWS of BOOKS January Moderating and Restraining Her Ally

102 BE VIEWS OF BOOKS January moderating and restraining her ally. The German intention, however, was that the French should desert their ally, while the Germans remained faithful to theirs (see Kiderlen's minute in Orosse Poliiik, xxvi. no. 9367); and this is what in fact happened. By concentrating on Morocco, the French were not improving their position in Europe; they were in danger of losing it altogether. The Bosnian crisis was to show that France could win German friendship only by abandoning Russia ; and the Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ehr/article/LXVII/CCLXII/102/460932 by guest on 27 September 2021 Agadir crisis that she could win it only by abandoning Great Britain. The volumes under notice have suffered casualties of war, not only in the delay of their publication. Volume ix was evidently prepared before the outbreak of war in 1939, and has no defects. Documents taken from the files for publication in volume x were destroyed in the fire of 25 August 1944 at the Quai d'Oreay ; not all could be replaced from embassy archives. When the Commission came to work on volume xi, they found that entire files had been removed by the Germans. These included the political correspondence with Austria-Hungary, Spain, Italy, the United States, and Turkey ; all files connected with general Balkan affairs and some connected with Morocco. Though the files of telegrams and the registers remained intact, there is evidence of losses which could not be made good. Attention has been drawn above to one such possible gap in October 1908 ; and there are other obvious gaps in Jules Cambon's correspondence from Berlin. -

Appendix a Senior Officials of the Foreign Office, 1936-381

Appendix A Senior Officials of the Foreign Office, 1936-381 Appointed * Rt. Hon. Anthony Eden, MC, MP (Sec retary of State for Foreign Affairs) 22 Dec. I935 Sir Robert Gilbert Vansittart, GCMG, KCB, MVO (Permanent Under-Secretary of State) I Jan. I930 * Viscount Cranborne, -MP (Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State) 5 Aug. I935 Rt. Hon. the Earl of Plymouth (Parliamen tary Under-Secretary of State) I Sept. I936 Capt. Rt. Hon. Euan Wallace, MC, MP (Additional Parliamentary Under-Sec retary of State) 28 Nov. I935 * Halifax's appointment as Foreign Secretary announced 25 February 1938. * R. A. Butler's appointment as Parliamentary Under-Secretary announced 25 February 1938. Deputy Under-Secretaries of State Hon. Sir Alexander M.G. Cadogan, KCMG, CB I Oct. I936 Sir Lancelot Oliphant, KCMG, CB (Superin tending Under-Secretary, Eastern De partment) I Mar. 216 Appendix A 2I7 Appointed Assistant Under-Secretaries of State Sir George Augustus Mounsey, KCMG, CB, OBE I5 July I929 Sir Orme Garton Sargent, KCMG, CB (Superintending Under-Secretary, Central Department) I4 Aug. I933 Sir Robert Leslie Craigie, KCMG, CB I5 Jan. I935 Charles Howard Smith, CMG (Principal Establishment Officer) 22 Aug. I933 Sir Frederick G. A. Butler, KCMG, CB (Finance Officer) 22 Aug. Sir Herbert William Malkin, GCMG, CB, KC (Legal Adviser) I Oct. I929 William Eric Beckett, CMG (Second Legal Adviser) I Oct. Gerald Gray Fitzmaurice (Third Legal Adviser) 6 Nov. Montague Shearman, OBE (Claims Adviser) I Oct. Counsellors (in order rif appointment to Counsellors' posts) Charles William Orde, CMG I5 July I929 George Nevile Maltby Bland, CMG 14 Nov. -

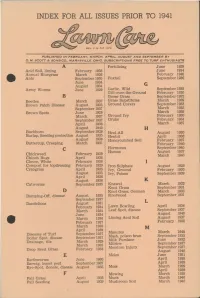

INDEX for ALL ISSUES PRIOR to 1941 C

r INDEX FOR ALL ISSUES PRIOR TO 1941 PUBLISHED IN FEBRUARY, MARCH, APRIL, AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER BY O. M. SCOTT & SONS CO., MARYSVILLE. OHIO. SUBSCRIPTIONS FREE TO TURF ENTHUSIASTS Fertilizing June 1929 Acid Soil, liming February 1938 June 1934 Annual Bluegrass March 1936 February 1940 Ants September 1930 Foxtail September 1936 June 1934 August 1934 G Army Worms June 1929 Garlic, Wild September 1938 Gill-over-the-Ground February 1930 B Goose Grass September 1932 Beetles March 1937 Grass Substitutes March 1939 Brown Patch Disease August 1935 Ground Covers September 1933 September 1937 March 1935 Brown Spots June 1929 March 1939 March 1937 Ground Ivy February 1930 September 1937 Grubs February 1934 April 1938 March 1937 August 1940 H Buckhorn September 1929 Heal-All August 1930 Burlap, Seeding protection August 1935 Henbit April 1936 August 1938 Honeycombed Soil February 1937 Buttercup, Creeping March 1931 February 1940 Hormones September 1940 c Humus August 1937 Chickweed February 1939 March 1940 Chinch Bugs April 1938 Clover, White February 1936 I Compost for topdressing February 1929 Iron Sulphate August 1929 Crabgrass April 1935 Ivy, Ground February 1930 August 1935 Ivy, Poison September 1939 April 1936 August 1936 K Cutworms September 1935 Knawel March 1933 Knot Grass September 1931 D Knot Grass, German March 1933 Damping-Off, disease August 1935 Knotweed September 1931 September 1937 Dandelions August 1931 L February 1934 Lawn Bowling April 1936 March 1934 Leaf Spot, disease September 1937 June 1934 August 1940 March 1936 Liming Acid