Boston Basin Restudied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massachuse S Bu Erflies

Massachuses Bueries Spring 2020, No. 54 Massachusetts Butteries is the semiannual publication of the Massachusetts Buttery Club, a chapter of the North American Buttery Association. Membership in NABA-MBC brings you American Butteries and Buttery Gardener . If you live in the state of Massachusetts, you also receive Massachusetts Butteries , and our mailings of eld trips, meetings, and NABA Counts in Massachusetts. Out-of-state members of NABA-MBC and others who wish to receive Massachusetts Butteries may order it from our secretary for $7 per issue, including postage. Regular NABA dues are $35 for an individual, $45 for a family, and $70 outside the U.S, Canada, or Mexico. Send a check made out to “NABA” to: NABA, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960 . NABA-MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLY CLUB Ofcers: President : Steve Moore, 400 Hudson Street, Northboro, MA, 01532. (508) 393-9251 [email protected] Vice President-East : Martha Gach, 16 Rockwell Drive, Shrewsbury, MA ,01545. (508) 981-8833 [email protected] Vice President-West : Bill Callahan, 15 Noel Street, Springeld, MA, 01108 (413) 734-8097 [email protected] Treasurer : Elise Barry, 363 South Gulf Road, Belchertown, MA, 01007. (413) 461-1205 [email protected] Secretary : Barbara Volkle, 400 Hudson Street, Northboro, MA, 01532. (508) 393-9251 [email protected] Staff Editor, Massachusetts Butteries : Bill Benner, 53 Webber Road, West Whately, MA, 01039. (413) 320-4422 [email protected] Records Compiler : Mark Fairbrother, 129 Meadow Road, Montague, MA, 01351-9512. [email protected] Webmaster : Karl Barry, 363 South Gulf Road, Belchertown, MA, 01007. (413) 461-1205 [email protected] www.massbutteries.org Massachusetts Butteries No. -

The Bedrock Geology and Fracture Characterization of the Maynard Quadrangle of Eastern Massachusetts

The Bedrock Geology and Fracture Characterization of the Maynard Quadrangle of Eastern Massachusetts Author: Tracey A. Arvin Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1731 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2010 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Geology and Geophysics THE BEDROCK GEOLOGY AND FRACTURE CHARACTERIZATION OF THE MAYNARD QUADRANGLE OF EASTERN MASSACHUSETTS a thesis by TRACEY ANNE ARVIN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science December 2010 © copywrite by TRACEY ANNE ARVIN 2010 ABSTRACT The bedrock geology of the Maynard quadrangle of east-central Massachusetts was examined through field and petrographic studies and mapped at a scale of 1:24,000. The quadrangle spans much of the Nashoba terrane and a small area of the Avalon terrane. Two stratigraphic units were defined in the Nashoba terrane: the Cambrian to Ordovician Marlboro Formation and the Ordovician Nashoba Formation. In addition, four igneous units were defined in the Nashoba terrane: the Silurian to Ordovician phases of the Andover Granite, the Silurian to Devonian Assabet Quartz Diorite, the Silurian to Devonian White Pond Diorites (new name), and the Mississippian Indian Head Hill Igneous Complex. In the Avalon terrane, one stratigraphic unit was defined as the Proterozoic Z Westboro Formation Mylonites, and one igneous unit was defined as the Proterozoic Z to Devonian Sudbury Valley Igneous Complex. Two major faults were identified: the intra-terrane Assabet River fault zone in the central part of the quadrangle, and the south-east Nashoba terrane bounding Bloody Bluff fault zone. -

2020 Coastal Massachusetts COASTSWEEP Results (People

COASTSWEEP 2020 - Cleanup Results Town Location Group Name People Pounds Miles TOTALS 703 9016.2 151.64 Arlington Mystic River near River Street 1 2 Arlington Mystic River 1 2.12 1.20 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 4 27.5 3.95 Barnstable Jublilation Way, Osterville 1 0.03 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 2 10.13 0.53 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 1 8 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 2 8.25 1.07 Barnstable Sandy Neck Beach Take Care Cape Cod 3 14.25 1.16 Barnstable Oregon Beach, Cotuit 6 30 Barnstable KalMus Park Beach 2 23.63 0.05 Barnstable Dowes Beach, East Bay Cape Cod Anti-Litter Coalition 4 25.03 0.29 Barnstable Osterville Point, Osterville Cape Cod Anti-Litter Coalition 1 3.78 0.09 Barnstable Louisburg Square, Centerville 2 Barnstable Hathaway's Ponds 2 4.1 0.52 Barnstable Hathaway's Ponds 2 5.37 0.52 Barnstable Eagle Pond, Cotuit Lily & Grace Walker 2 23.75 3.26 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 2 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.07 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.03 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.11 0.02 Beverly Corning Street SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.18 0.01 Beverly Dane Street Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.36 0.04 Beverly Clifford Ave 2 11.46 0.03 Beverly Near David Lynch Park 1 0.43 0.03 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 3 28.61 0.03 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 3 1.61 Beverly Rice's Beach SaleM Sound Coastwatch 1 0.07 COASTSWEEP 2020 - Cleanup Results Town -

Statistical Framework for Water Quality Load Estimation

Water Tuftsand University People Environmental Studies Lunch & Learn Richard M. Vogel Oct 20, 2011 Tufts University Medford, MA Outline Tufts University Emerging Issues: Water and People: Some Big Problems Water Supply – Boston Metro Region Water and Urbanization Water and Climate Water and Food Water and Human Water Use Outline Tufts University Emerging Issues: Water and People: An Intro to some big problems Water and Health Water Supply – NYC and Boston Water and Urbanization Water and Climate Water and Food Water and Human Water Use Water and People: Why do people know so little about water? Tufts University Hydrologic science is an interdisciplinary science which involves the interfaces among earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences. Hydrology is a geoscience Why isn‟t it taught like geology, biology, meteorology, or chemistry? Water Problems are Human Problems Tufts University Global Population Growth 10 8 6 4 2 Population in Billions in Population 0 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000 2200 YEAR (AD) Water Problems Result From Human Influences and they are Ramping Up Tufts University Water and People Tufts University Water Pollution and Water Scarcity Are the two biggest water challenges of the 21st Century Water and People Tufts University Today, 1 out of 6 people, more than a billion Suffer from inadequate access to safe freshwater Tufts University Water and Poverty Tufts University Irrigation can lift rural poor out of poverty Tufts University Average income levels & irrigation intensity in India Income per capita Income -

Mineral Industries and Geology of Certain Areas

REPORT -->/ OF TFIE STATE GEOLOGIST ON THE S 7 (9 Mineral Industries and Geology 12 of Certain Areas OF -o VERMONT. 'I 6 '4 4 7 THIRD OF THIS SERIES, 1901-1902. 4 0 4 S GEORGE H. PERKINS, Ph. D., 2 5 State Geologist and Professor of Geology, University of Vermont 7 8 9 0 2 4 9 1 T. B. LYON C0MI'ANV, I'RINTERS, ALILiNY, New VORK. 1902. CONTENTS. PG K 1NTRODFCTION 5 SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF ZADOCK THOMPSON, G. H. Perkins ----------------- 7 LIST OF OFFICIAL REPORTS ON VERMONT GEOLOGY ----------------- -- -- ----- 14 LIST OF OTHER PUBLICATIONS ON VERMONT GEOLOGY ------- - ---------- ----- 19 SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF AUGUSTUS WING, H. M. Seely -------------------- -- 22 REPORT ON MINERAL INDUSTRIES, G. H. Perkins ............................ 35 Metallic Products ------------------------------------------------------ 32 U seful Minerals ------------------------------------------------------- 35 Building and Ornamental Stone ----------------------------------------- 40 THE GRANITE AREA OF BAItRE, G. I. Finlay------------------------------ --- 46 Topography and Surface Geology ------------------------------------ - -- 46 General Geology, Petrography of the Schists -------------------------- - -- 48 Description and Petrography of Granite Areas ----------------------------51 THE TERRANES OF ORANGE COUNTY, VERMONT, C. H. Richardson ------------ 6i Topography---------------------------- -............................. 6z Chemistry ------------------------------------------------------------66 Geology -------------------------------------------------------------- -

Larson Fisher Associates, Inc

Larson Fisher Associates, Inc. Historic Preservation and Planning Services P.O. Box 1394 Woodstock, N.Y. 12498 845-679-5054 www.larsonfisher.com COASTAL ZONE HISTORIC RESOURCE SURVEY Marblehead, Essex County, Massachusetts Final Report 18 September 2016 Abstract The project conducted an intensive-level survey of historic resources within the coastal zone established by the Town of Marblehead. This project was the top priority in the Town’s Historic Resource Survey Master Plan (2013) as historic properties on the coastline are considered to be most vulnerable to change. The goal of the survey is to promote the preservation of these valuable properties by raising public awareness of their significance through detailed and cogent narratives of their individual histories and their role as landmarks in the evolving physical and cultural character of their neighborhoods. In addition, the local Marblehead Historical Commission (LHC) desired to upgrade existing levels of documentation and provide information useful in the evaluation of significance for preservation planning and the town’s review of permit applications involving historic properties. The LHC has no direct jurisdiction in project review but hopes survey documentation will lead to informed decisions where significant historic resources are involved. This project recorded architectural, historical and photographic documentation for 186 properties in the coastal zone on survey forms for individual properties and areas provided by the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC). Individual properties and historic districts that appear eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places have been identified. Due to the large number of properties documented, exceeding the contractual obligation of 120 properties, those on Marblehead Neck were deferred to a later project with one exception. -

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries 2018 Annual Report

Department of Fish and Game Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries 2018 Annual Report Atlantic cod, post‐release. Photography by Steve de Neef. Division staff conducting fyke net sampling for rainbow smelt on the north shore Department of Fish and Game Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries 2018 Annual Report Commonwealth of Massachusetts Governor Charles D. Baker Lieutenant Governor Karyn E. Polito Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Secretary Matthew A. Beaton Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Ronald Amidon Division of Marine Fisheries Director David E. Pierce, Ph.D. www.mass.gov/marinefisheries January 1–December 31, 2018 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries 2018 Annual Report 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Frequently Used Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................. 6 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT SECTION ....................................................................................................................... 7 Fisheries Policy and Management Program ...................................................................................................... 7 Personnel ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Overview ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Town of Upton Open Space and Recreation Plan

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ MAY 2011 TOWN OF UPTON D OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN a f North t Prepared by: Upton Open Space Committee (A Subcommittee of the Upton Conservation Commission) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Town of Upton D OPEN SPACE rAND RECREATION PLAN a f t May 2011 Prepared by: The Upton Open Space Committee (A Subcommittee of the Upton Conservation Commission) Town of Upton Draft Open Space and Recreation Plan – May 2011 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ DEDICATION The members of the Open Space Committee wish to dedicate this Plan to the memory of our late fellow member, Francis Walleston who graciously served on the Milford and Upton Conservation Commissions for many years. __________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Upton Open Space Committee Members Tom Dodd Scott Heim Rick Holmes Mike Penko Marcella Stasa Bill Taylor Assistance was provided by: Stephen Wallace (Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission) Peter Flinker and Hillary King (Dodson Associates) Dave Adams (Chair, Upton Recreation Commission) Chris Scott (Chair, Upton Conservation Commission) Ken Picard (as a Member of the Upton Planning Board) Upton Board of Selectmen. Trish Settles (Central Massachusetts Regional Planning Commission) __________________________________________________________________ -

Marblehead Reconnaissance Report

MARBLEHEAD RECONNAISSANCE REPORT ESSEX COUNTY LANDSCAPE INVENTORY MASSACHUSETTS HERITAGE LANDSCAPE INVENTORY PROGRAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Essex National Heritage Commission PROJECT TEAM Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Jessica Rowcroft, Preservation Planner Division of Planning and Engineering Essex National Heritage Commission Bill Steelman, Director of Heritage Preservation Project Consultants Shary Page Berg Gretchen G. Schuler Virginia Adams, PAL Local Project Coordinator Rebecca Curran, Town Planner Local Heritage Landscape Participants Wayne Butler Rebecca Curran Bill Conly Charlie Dalferro Joseph Homan Bette Hunt Judy Jacobi John Liming Frank McIver Ed Nilsson Miller Shropshire William Woodfin May 2005 INTRODUCTION Essex County is known for its unusually rich and varied landscapes, which are represented in each of its 34 municipalities. Heritage landscapes are places that are created by human interaction with the natural environment. They are dynamic and evolving; they reflect the history of the community and provide a sense of place; they show the natural ecology that influenced land use patterns; and they often have scenic qualities. This wealth of landscapes is central to each community’s character; yet heritage landscapes are vulnerable and ever changing. For this reason it is important to take the first steps towards their preservation by identifying those landscapes that are particularly valued by the community – a favorite local farm, a distinctive neighborhood or mill village, a unique natural feature, an inland river corridor or the rocky coast. To this end, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and the Essex National Heritage Commission (ENHC) have collaborated to bring the Heritage Landscape Inventory program (HLI) to communities in Essex County. -

Hydrology of Massachusetts

Hydrology of Massachusetts Part 1. Summary of stream flow and precipitation records By C. E. KNOX and R. M. SOULE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1105 Prepared in cooperation with Massachusetts Department of Public ff^orks This copy is, PI1R1rUDLIt If PROPERTYr nuri-i LI and is not to be removed from the official files. JJWMt^ 380, POSSESSION IS UNLAWFUL (* s ' Sup% * Sec. 749) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1949 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR J. A. Kruft, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. G. - Price 91.00 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Introduction........................................................ 1 Cooperation and acknowledgments..................................... 3 Explanation of data................................................. 3 Stream-flow data.................................................. 3 Duration tables................................................... 5 Precipitation data................................................ 6 Bibliography........................................................ 6 Index of stream-flow records........................................ 8 Stream-flow records................................................. 9 Merrimack River Basin............................................. 9 Merrimack River below. Concord River, at Lowell, Mass............ 9 Merrimack River at Lawrence, Mass............................... 10 North Nashua River near Leominster, -

Fracture Characterization Mapping for Regional Geologic Studies: the Hydrostructural Domain Approach, Ayer Quadrangle, Massachusetts

Fracture Characterization Mapping for Regional Geologic Studies: The Hydrostructural Domain Approach, Ayer Quadrangle, Massachusetts Stephen B. Mabee And Joseph P. Kopera Office of the Massachusetts State Geologist Geosciences Department University of Massachusetts 611 North Pleasant Street Amherst, MA 01003 Abstract While traditional bedrock geologic maps contain valuable information, they commonly lack data on brittle fracture characteristics and distributions. The increased need for better understanding of groundwater flow behavior in bedrock aquifers has made this data critical. The concept of hydrostructural domains is used to redefine bedrock mapping units based on an assemblage of lithologic and fracture characteristics thought to be important controls on groundwater flow and recharge. These maps are constructed from detailed field observations and measurements of 2000-3000 fractures from 60-70 stations across a 7.5' quadrangle. Hydrostructural domains are displayed on the map as traditional lithologic units would be, with detailed descriptions and photos of the fracture systems contained in each hydrostructural “unit”. In the Ayer quadrangle, such domains closely correspond with bedrock lithology and ductile structural history. Steeply dipping metasedimentary rocks of the Merrimack Belt have pervasive, closely spaced, throughgoing fractures developed parallel to foliation, and therefore may provide excellent potential for vertical recharge and foliation-parallel flow. Where these rocks are intensely cut by a strong subhorizontal cleavage, a parallel fracture set dominates providing an opportunity for lateral flow. Massive granites generally have a well-developed, widely-spaced orthogonal network of fracture zones which may provide excellent local recharge. High-grade gneisses of the Nashoba formation have poorly developed fracture sets except near regional shear zones, where foliation parallel fractures and cross-joints may provide good vertical recharge and provide a strong northeast trending flow anisotropy. -

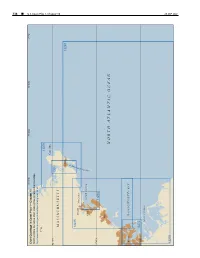

CPB1 C10 WEB.Pdf

338 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 Chapter 1, Pilot Coast U.S. 70°45'W 70°30'W 70°15'W 71°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 1—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 13279 Cape Ann 42°40'N 13281 MASSACHUSETTS Gloucester 13267 R O B R A 13275 H Beverly R Manchester E T S E C SALEM SOUND U O Salem L G 42°30'N 13276 Lynn NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Boston MASSACHUSETTS BAY 42°20'N 13272 BOSTON HARBOR 26 SEP2021 13270 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 1, Chapter 10 ¢ 339 Cape Ann to Boston Harbor, Massachusetts (1) This chapter describes the Massachusetts coast along and 234 miles from New York. The entrance is marked on the northwestern shore of Massachusetts Bay from Cape its eastern side by Eastern Point Light. There is an outer Ann southwestward to but not including Boston Harbor. and inner harbor, the former having depths generally of The harbors of Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Salem, 18 to 52 feet and the latter, depths of 15 to 24 feet. Marblehead, Swampscott and Lynn are discussed as are (11) Gloucester Inner Harbor limits begin at a line most of the islands and dangers off the entrances to these between Black Rock Danger Daybeacon and Fort Point. harbors. (12) Gloucester is a city of great historical interest, the (2) first permanent settlement having been established in COLREGS Demarcation Lines 1623. The city limits cover the greater part of Cape Ann (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are and part of the mainland as far west as Magnolia Harbor.