Helping Students Find Meaning While Finding My Own: a Scholarly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank Marvin Album HANK Set for Release 2Nd June 2014 Submitted By: Bennett Public Relations Thursday, 10 April 2014

Hank Marvin album HANK set for release 2nd June 2014 Submitted by: Bennett Public Relations Thursday, 10 April 2014 Hank Marvin, the legendary guitarist and modern day icon, who has inspired generations and garnered critical acclaim throughout his career for his work with The Shadows and as a solo artist, releases a long-awaited new studio album on 2 June 2014. Simply titled HANK, the album will be released on the DMG TV label. Featuring 14 tracks, HANK includes fresh interpretations of some of Marvin’s favourite summer-themed music, along with one new composition. It’s the first new release since 2007’s UK Top 10 Guitar Man, for the man whose legendary achievements were restated yet again in The Times in February 2014, when he was listed as Number 2, amongst the world’s greatest guitar players and The Shadows amongst the greatest groups! It’s been 60 years since the man who introduced the Fender Stratocaster to the UK, picked up his first musical instrument. Marvin’s performances as a solo frontman and with The Shadows on their records and backing Cliff Richard have resulted in millions of worldwide record sales. The Shadows’ monumental chart debut with Apache in 1960 started an incredible run of 13 UK Top 10 hits for the group in just 4 years, during which time their unmistakeable style became a household sound around the world. Hank and The Shadows ruled the charts during the early 1960s and as a solo artist from the late 1970s to the present day Hank Marvin has sold in excess of 6 million albums. -

Word~River Literary Review (2013)

word~river Publications (ENG) Spring 2013 word~river literary review (2013) Ross Talarico Palomar College, [email protected] Anne Stark Utah State University, [email protected] Susan Evans East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Gary Pullman University of Nevada, Las Vegas; College of Southern Nevada, [email protected] Andrew Madigan Al Ain City College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/word_river Part of the American Literature Commons, Creative Writing Commons, and the Literature in English, NorSeeth next America page forCommons additional authors Recommended Citation Talarico, Ross; Stark, Anne; Evans, Susan; Pullman, Gary; Madigan, Andrew; Taylor, Christin; Melancon, Jerome; Evenson, Jennie; Mansour, Judith; DiDomenico, Mary; Lampman, Annie; Foster, Maureen; Montgomery, M. V.; Johnson, Rowan; Hanley, James; Brantley, Michael K.; Rexroat, Brooks P.; Stark, Deborah; Johnson, Rachel Rinehart; Crooks, Joan; Navicky, Jefferson; Higgins, Ed; Bezemek, Mike; Fields- Carey, Leatha; and Winfield, Maria, "word~river literary review (2013)" (2013). word~river. 5. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/word_river/5 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Book in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Book has been accepted for inclusion in word~river by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. -

Neil Young a Perfect Echo Volume 2 (1989-2001) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Neil Young A Perfect Echo Volume 2 (1989-2001) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: A Perfect Echo Volume 2 (1989-2001) Country: Japan Released: 2004 Style: Classic Rock, Folk Rock, Country Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1528 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1542 mb WMA version RAR size: 1205 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 298 Other Formats: MP3 AC3 AU XM WAV AIFF DTS Tracklist 1-1 Rockin' In The Free World (Hamburg, Germany, 8-Dec-1989) 1-2 Don't Let It Bring You Down (Hamburg, Germany, 8-Dec-1989) 1-3 After The Gold Rush (Hamburg, Germany, 8-Dec-1989) 1-4 Ohio (Hamburg, Germany, 8-Dec-1989) 1-5 Too Far Gone (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-6 Crime In The City (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-7 Eldorado (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-8 Hangin' On A Limb (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-9 Someday (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-10 My My Hey Hey (Amsterdam, Holland, 10-Dec-1989) 1-11 The Old Laughing Lady (Paris, France - 11-Dec-1989) 1-12 The Needle And The Damage Done (Paris, France - 11-Dec-1989) 1-13 No More (Paris, France - 11-Dec-1989) 1-14 Days That Used To Be (Mountain View, CA, 26-Oct-1990) 1-15 Mansion On The Hill (Mountain View, CA, 26-Oct-1990) 2-1 Love And Only Love (Mountain View, CA, 26-Oct-1990) 2-2 Forever Young (San Francisco, CA, 3-Nov-1991) 2-3 Harvest Moon (Irving, TX, 14-Mar-1992) 2-4 Unknown Legend (Irving, TX, 14-Mar-1992) 2-5 Dreamin' Man (Chicago, IL, 17-Nov-1992) 2-6 You And Me (Chicago, IL, 17-Nov-1992) 2-7 Natural Beauty (Chicago, IL, 17-Nov-1992) 2-8 From Hank To Hendrix (Ames, IA, 24-Apr-1993) -

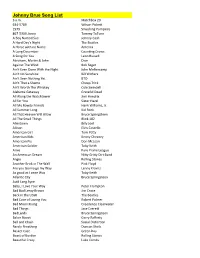

Johnny Brue Song List.Xlsx

Johnny Brue Song List 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 634-5789 Wilson Picke 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 867-5309 Jenny Tommy TuTone A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash A Hard Day's Night The Beatles A Horse with no Name America A Long December Counng Crows A Song for You Leon Russell Abraham, Marn & John Dion Against The Wind Bob Seger Ain't Even Done With the Night John Mellencamp Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't Seen Nothing Yet BTO Ain't That a Shame Cheap Trick Ain't Worth The Whiskey Cole Swindell Alabama Getaway Grateful Dead All Along the Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All for You Sister Hazel All My Rowdy Friends Hank Williams, Jr. All Summer Long Kid Rock All That Heaven Will Allow Bruce Springsteen All The Small Things Blink 182 Allentown Billy Joel Allison Elvis Costello American Girl Tom Pey American Kids Kenny Chesney American Pie Don McLean American Soldier Toby Keith Amie Pure Prarie League An American Dream Niy Griy Dirt Band Angie Rolling Stones Another Brick in The Wall Pink Floyd Are you Gonna go my Way Lenny Kravitz As good as I once Was Toby Keith Atlanc City Bruce Springsteen Auld Lang Syne Baby, I Love Your Way Peter Frampton Bad Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Back in the USSR The Beatles Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Bad Things Jace Evere BadLands Bruce Springsteen Baker Street Gerry Rafferty Ball and Chain Social Distoron Barely Breathing Duncan Sheik Basket Case Green Day Beast of Burden Rolling Stones Beauful Crazy Luke Combs Johnny Brue Song List Beds are Burning Midnight Oil Beer for my Horses Toby -

The James Taylor Encyclopedia

The James Taylor Encyclopedia An unofficial compendium for JT’s biggest fans Joel Risberg GeekTV Press Copyright 2005 by Joel Risberg All rights reserved Published 2005 Printed in the United States of America James Taylor Online www.james-taylor.com [email protected] Cover photo by Joana Franca. This book is not approved or endorsed by James Taylor, his record labels, or his management. For Sandra, who brings me snacks. CONTENTS BIOGRAPHY 1 TIMELINE 16 SONG ORIGINS 27 STUDIO ALBUMS 31 SINGLES 43 WORK ON OTHER ALBUMS 44 OTHER COMPOSITIONS 51 CONCERT VIDEOS 52 SINGLE-SONG MUSIC VIDEOS 57 APPEARANCES IN OTHER VIDEOS 58 MISCELLANEOUS WORK 59 NON-U.S. ALBUMS 60 BOOTLEGS 63 CONCERTS ON TELEVISION 70 RADIO APPEARANCES 74 MAJOR LIVE PERFORMANCES 75 TV APPEARANCES 76 MAJOR ARTICLES AND INTERVIEWS 83 SHEET MUSIC AND MUSIC BOOKS 87 SAMPLE SET LISTS 89 JT’S FAMILY 92 RECORDINGS BY JT ALUMNI 96 POINTERS 100 1971 Time cover story – and nearly every piece of writing about James Taylor since then – characterized the musician Aas a troubled soul and the inevitable product of a family of means that expected quite a lot of its kids. To some extent, it was true. James did find inspiration for much of his life’s work in his emotional torment and the many years he spent fighting drug addiction and depression. And he did hail from an affluent, musically talented family that could afford to send its progeny to exclusive prep schools and expensive private mental hospitals. But now James Taylor in his fifties has the benefit of hindsight to moderate any lingering grudges against a press that persistently pigeonholed him – first as a sort of Kurt Cobain of his day, and much later as a sleepy crooner with his most creative years behind him. -

P20-21 Layout 1

20 Established 1961 Lifestyle Gossip Wednesday, July 17, 2019 oren has signed a worldwide publishing deal with A&G Songs view with BANG Showbiz, she said: “I hope so, I think many people L and A&G Sync. The 27-year-old singer - formerly known as assume when you’ve got so far on a television show, you’ve made it. Lauren Bannon - is taking her career to the next level after When really it actually takes a lot of time and hard work - that kind of appearing on the ITV talent show last year, and has landed exposure can only be the beginning. “I’m grateful to the show for giving herself a major deal with the London-based publishing and sync agency. me a platform, but I’m aware to cut it as an artist I’ve got to be more The founder and CEO of A&G Songs and A&G Sync, Roy Lidstone, was than just a pretty voice from a TV show.” Lloren was mentored by Olly introduced to the rising star earlier this year, after seeing her perform at Murs on the show, and asked whether she and the ‘Dear Darlin” hitmaker an A&R session, and he was drawn to her “incredible” talent for writing - who shot to fame on ‘The X Factor’ in 2009 - stay in touch, she said: as well as her impressive vocals. On the signing, he said: “One of A&G “Of course, we still talk and I saw him at an event a few months ago!” Songs strengths is its sync agency, A&G Sync. -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 02 of September 28 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 02 of September 28 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part one Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his At a time when so many of the inspired and recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the inspiring musicians of the 1960s and 1970s have seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo become parodies of their former selves with little Springfield, with the release of this band’s or nothing of any artistic substance to contribute eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo to rock culture, Young’s heart continues to studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still pound with passion – and this is the dominant on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, spirit of his new album. This work is reviewed in war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the the next edition of Strange Brew (edition three: demise of human decency. Michael Waddacor Neil Young, part two). Living with War is an pays tribute the Canadian-born songwriter and imploring, heart-felt cry for a return to human musician for his unrelenting courage and decency and freedom from the malaise of uncompromising individualism in a world gone modern living: Third World exploitation, debt crazy and short of adorable eccentrics in the and misery, idiotic political and business realms of rock music. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Anomalies, Warts and All: Four Score of Liberty, Privacy and Equality Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2004 Anomalies, Warts and All: Four Score of Liberty, Privacy and Equality Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Francisco Valdes, Anomalies, Warts and All: Four Score of Liberty, Privacy and Equality, 65 Ohio St. L.J. 1341 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anomalies, Warts and Al: Four Score of Liberty, Privacy and Equality FRANCISCO VALDES* Lawrence was decided exactly eighty years after the first liberty-privacy case, and in the midst of a fierce kulturkampf striving to roll back civil rights generally. In this Article, Professor Valdes situates Lawrence in the context formed both by these four score of liberty-privacyjurisprudence that precede it as well as by the politics of backlash that envelop it today. After canvassing the landmark rulings from Meyer in 1923 to Lawrence in 2003, in the process acknowledging both their emancipatory strengths and their traditionalist instrumentalism, Professor Valdes concludes that Lawrence is a long overdue recognition of the prior precedents and their actual outcomes. -

“Missing” Recordings

NEIL YOUNG UNRELEASED - ARCHIVE INFORMATION NEIL YOUNG’S “MISSING” RECORDINGS including Songs officially released on audio media but not released as audio files in Neil Young Archives Songs, official outtakes and demos released as audio files in Neil Young Archives but not released on official Neil Young Albums An NYU Publication facebook.com/groups/ny.unreleased.nyu twitter.com/UnreleasedNeil @UnreleasedNeil Robert Broadfoot [email protected] Version 4.0, 21 May 2021 © Robert Broadfoot 2021 ............................................................................................................................................................................................ NEIL YOUNG’S “MISSING” RECORDINGS ©Robert Broadfoot 2021 • [email protected] 1 Version 4.0, 21 May 2021 CONTENTS I. SONGS OFFICIALLY RELEASED ON AUDIO MEDIA BUT NOT RELEASED AS AUDIO FILES IN NEIL YOUNG ARCHIVES PART ONE NEIL YOUNG RECORDINGS ....................................................................................... 4 PART TWO GUEST APPEARANCES ............................................................................................. 27 PART THREE MEDIA NETWORK OFFICIAL RELEASES .................................................................... 38 II. SONGS, OFFICIAL OUTTAKES AND DEMOS RELEASED AS AUDIO FILES IN NEIL YOUNG ARCHIVES BUT NOT RELEASED ON OFFICIAL NEIL YOUNG ALBUMS .................................................................. 47 NOTES Version 4.0 This version of ‘Missing’ represents a complete restructuring -

1956 Bubblegum Disaster

1956 BUBBLEGUM DISASTER TUNING: EADGBE SUBMITTED BY: Fredrik Johansson CHORDS: F Am Dm C Bb F/E G Bb Gm F F Am Dm oh-ie baby, nineteenfiftysix F C Bb F has come a long, long way Neil speaks: How do you like that, ey folks? Took me three years to write that. Here''s another one while we''re on those long ones. F F/E Dm G Bb F F/E Dm Gm C F F/E Dm There was a guy where I was from G Bb mothered his dog in bubblegum F F/E Dm Gm C how sad, couldn''t belive he''d be that bad F SongX.se - The Neil Young Songbook (updated 2020-11-14) A DREAM THAT CAN LAST TUNING: EADGBE SUBMITTED BY: Wolfgang Deimel CHORDS: C G F Em Am INTRO: C G F G C C G F G C I feel like I died and went to heaven G F G C The cupboards are bare but the streets are paved with gold G F C I saw a young girl who didn't die G F C I saw a glimmer from in her eye Em Am I saw the distance I saw the past F G And I know I won't awaken, it's a dream that can last SongX.se - The Neil Young Songbook (updated 2020-11-14) A MAN NEEDS A MAID TUNING: EADGBE SUBMITTED BY: Matt Mohler CHORDS: C Dm F Bb F C G Bb Dm Dm C My life is changin' in so many ways Bb F I don't know who to trust anymore Dm C There's a shadow runnin' through my days Bb Dm Like a beggar goin' from door to door Dm C I was thinkin' that maybe I'd get a maid Bb F Find a place nearby for her to stay Dm Am7 Just someone to keep my house clean Bb Dm Fix my meals and go away Dm C Bb Dm G F Em A ma a a aid a man needs a maid Dm C Bb Dm A ma a a aid |Em |Em7 |F | C|Em |Em7 |F |Csus C Am G F Em7 Dm7 It's hard to make that change Am -

Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021

1 of 188 Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021 To Search: Ctrl + F Search box will appear. Type in a keyword, then hit Enter. Apple Computers to Search: Command F Club / Activity Name Location Leader Group Website Email Address Phone Number CSS La .45 Sidekicks - Call for Info Hacienda Kevin Yeo 1013 Amarillo Pl [email protected] (605) 999-7687 129 Amigos qF@6PM Coconut Cove Linda Maloney NA [email protected] (352) 561-4808 CSS 152 & Friends - Call for Info SeaBreeze Barbara McGrath 1846 Barksdale Drive [email protected] (440) 821-5290 200 Ladies' Club 2,4W@9AM Burnsed Gail Hole 1011 Pickering Path [email protected] (970) 227-0003 2012 Discussion Group 2,4W@3PM Bridgeport Richard Matwyshen NA [email protected] (352) 751-0365 26er's Club 2Meven@6PM La Hacienda Barbara LoPiccolo 1320 Augustine Drive [email protected] (732) 618-7658 26er's West Ladies' Lunch 2TH@11:30AM El Santiago Marilynn Miller 501 Chamber Street [email protected] (262) 442-9805 2nd Honeymoon Club 1M@6:30PM Savannah Mitchell Sheinbaum www.2ndhoneymoonclub.com [email protected] (352) 751-4138 4 O'Clock Club 1Wx7,8@4PM Chula Vista Richard Petulla 518 Chula Vista [email protected] (352) 750-5641 4 Season Singles 2SA@5:30PM SeaBreeze Holly Weller NA [email protected] (352) 430-6007 5 Streets East 1SA2,5,10,12@6PM Burnsed Kathy Dawson 3518 Countryside Path [email protected] (352) 391-6446 A New Vibrant You 2W@6:30PM Laurel Manor Richard Matwyshen NA [email protected] (352) 751-0365 AARP DSP Colony Cottage Colony Cottage Chester Kowalski 2760 Midland Terrace [email protected] (352) 430-1833 AARP DSP Laurel Manor Laurel Manor Chester Kowalski 2760 Midland Terrace [email protected] (352) 430-1833 2 of 188 Resident Lifestyles Clubs and Contacts 8/27/2021 To Search: Ctrl + F Search box will appear.