C Emlen Urban: to Build Strong and Substantial Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

* ^Mwmi COMMON: Fulton Opera House

Theme 8: The Contemulative Society; Literature, Dramaand Music NHL Form 10-300 UNITED Si A "^DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ST-JTT c. (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Pennsylvania COUN1~Y: NATIONAL REG ISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Lancaster INVENTOR Y - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) * ^mwmi COMMON: Fulton Opera House AND/OR HISTORI C: Fulton Opera House ti^'WV r $r; v ^ ' %-" ,: ,,^^ ' <&t 'I/? *%%&' ' '"'" S^ll^- ,i STREET AND NUMBER: 12-14 N. Prince Street CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL D ISTRICT: Lancaster #16 STATE .CODE COUNTY: CODE Pennsylvania 42 Lancaster 71 fcllii^lliilifl&Ny £; fR: :"v" CATEGORY STATUS ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC n District 3 Building 1 1 Public Public Acquisition: Q Occupied Yes: . , r~1 Restricted D Site Q Structure £] Privote Q In Process r- ] Unoccupied ' ' . ,1x1 Unrestricted D Object ! | Both [ | Being Considered r i pJ reservotion work in progress ' I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 1 I Agricultural 1 1 Government | | Park [ | Transportation 1 1 Comments PI Commercial D Industrial [~1 Private Residence |~1 Other fSoectfv) D Educational D Mi "tary | | Reliqious (3 EntertainmegE^fc D Mu seum | | Scientific liiiiiiliiii&tt:^ .. ,i;-;;,,,/ ^-i, ,. ; :.»'. , ^ ; - . v- OWNER'S NAME:i|f The Fultorf Opera House Foundation, Mr. Albert Wohlsen, President STATE- Penn. STREET AND NUMBER: 12-14 N. Prince Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF Lancaster Pennsylvania 42 plliliiiilii:FlIiIi!i;:f>i;sc^i:Pij^i:;::: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF -

Lancaster District Economic Prospects: Update Report

Lancaster District Economic Prospects: Update Report Final September 2017 Contents Executive Summary 1 2. Summary of the 2015 report and findings 1 3. 2017 Update 3 4. Key strengths 13 5. Key weaknesses 15 6. Key opportunities 19 7. Key threats 22 8. Developing a strategy 23 Appendix 1: List of interviewees 26 Executive Summary Context and purpose 1.1 In 2015 the Council commissioned a review, ‘Lancaster District: Prospects and Recommendations for Achieving Economic Potential’. This report provides a concise update to that review, culminating in a SWOT analysis of the district’s economy and highlighting key differences with the 2015 review. 1.2 This document is not intended to be an economic strategy for the district. Rather it is intended that it helps to inform thinking on developing an economic strategy for Lancaster District and the matters that such a strategy might address. Matters for further consideration by the Council in developing its strategy are clearly highlighted throughout the report where relevant. Ultimately, the Council’s goal is for inclusive growth – that is that local people have the opportunity to participate in realising economic growth for the District and likewise, that the benefits of growth are shared among residents. A strategy for economic development should be considered as a route towards achieving this goal, and improving quality of place and life across Lancaster District. 1.3 The findings in this report have been informed by structured consultation with a selection of stakeholders including Peel Ports, Duchy of Lancaster, Marketing Lancashire, Lancaster and District Chamber of Commerce, Lancashire County Council, Lancaster University and Growth Lancashire. -

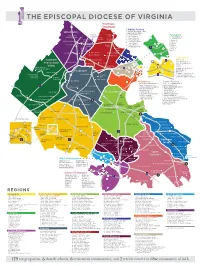

To Enlarge the Map

THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF VIRGINIA Northern 522 Piedmont North Fairfax Winchester Church of the Holy Cross, Dunn Loring (1) 15 Epiphany Episcopal, Oak Hill (2) Church of the Christ Church, Holy Comforter, Vienna (3) Arlington Shenandoah Valley 81 Good Shepherd, Lucketts St. Anne’s, Reston (4) Westminster-Canterbury La Iglesia de Cristo Rey (1) Bluemont St. Peter’s, St. Dunstan’s, McLean (5) 8 La Iglesia de San Jose (2) Grace Church, Purcellville St. James’, St. Francis, Great Falls (6) Leesburg St. Andrew’s (3) Christ Church, Winchester Berryville St. Francis Korean, McLean (7) St. George’s (4) 7 St. John’s, McLean (8) 6 3 St. John’s (5) St. Paul’s Church-on-the-Hill, St. Mary’s, St. Gabriel’s, St. Thomas, McLean (9) St. Mary’s (6) Winchester Berryville St. Timothy’s, Herndon (10) 7 Leesburg 66 St. Michael’s (7) Cunningham St. David’s, 2/4 St. Peter’s (8) Chapel Parish, Ashburn Trinity (9) Millwood Trinity, Upperville St. Matthew’s, Sterling Meade Memorial, White Post 6 Emmanuel, Middleburg 50 1/5 66 Church of Our Redeemer, 7 9 Leeds, Aldie 8 Alexandria Markham 9 Southern 340 Emmanuel, Delaplane 10 4 5/7 Christ Church (1) 1 7 395 Church of St. Clement (2) Calvary Church, Front Royal 3 11 Shenandoah Grace, The Plains 2 Church of the Resurrection (3) St. Andrew’s, 8 3 2 5 Marshall 11 Emmanuel (4) Valley St. Paul’s, Haymarket 4 2/9 Grace (5) Cathedral Shrine of the 6 10 66 1 Immanuel Church-on-the-Hill (6) Transfiguration, Orkney Springs 12 7 1 4 10 4 2/4 3 Meade Memorial (7) Culpeper 29 7 St. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

Lancaster County, PA Archives

Fictitious Names in Business Index 1917-1983 Derived from original indexes within the Lancaster County Archives collection 1001 Hobbies & Crafts, Inc. Corp 1 656 1059 Columbia Avenue Associates 15 420 120 Antiquities 8 47 121 Studio Gallery 16 261 1226 Gallery Gifts 16 278 1722 Motor Lodge Corp 1 648 1810 Associates 15 444 20th Century Card Co 4 138 20thLancaster Century Housing County,6 PA332 Archives 20th Century Television Service 9 180 222 Service Center 14 130 25th Hour 14 43 28th Division Highway Motor Court 9 225 3rd Regular Infantry Corp 1 568 4 R's Associates 16 227 4 Star Linen Supply 12 321 501 Diner 11 611 57 South George Street Associates 16 302 611 Shop & Gallery 16 192 7 Cousins Park City Corp 1 335 78-80 West Main, Inc. Corp 1 605 840 Realty 16 414 A & A Aluminum 15 211 A & A Credit Exchange 4 449 A & B Associates 13 342 A & B Automotive Warehouse Company Corp 1 486 A & B Electronic Products Leasing 15 169 A & B Manufacturing Company 12 162 A & E Advertising 15 54 A & H Collectors Center 12 557 A & H Disposal 15 56 A & H Drywall Finishers 12 588 A & L Marketing 15 426 A & L Trucking 16 358 A & M Enterprises 15 148 A & M New Car Brokers 15 128 A & M Rentals 12 104 A & P Roofing Company 14 211 A & R Flooring Service 15 216 A & R Nissley, Inc. Corp 1 512 A & R Nissley, Inc. Corp 1 720 A & R Nissley, Inc. Corp 2 95 A & R Tour Services Co. -

Pennsylvania

PENNSYLVANIA ANNUAL REPORT SUMMARY December 31, 2019 Prepared by the Office of the Controller Brian K. Hurter, Controller i Controller’s Office 150 North Queen Street Suite #710 Lancaster, PA 17603 Phone: 717-299-8262 Controller www.co.lancaster.pa.us Brian K. Hurter, CPA To the residents of Lancaster County: I am pleased and excited to provide you with our Annual Report Summary for the Fiscal Year Ended 2019. The information contained in this Report is a condensed and simplified overview of the County of Lancaster’s audited Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) for the year ended December 31, 2019. This Report presents selected basic information about Lancaster County’s revenues, spending, and demographics in an informal, easy to understand format. This Report is not intended to replace the larger more detailed CAFR. The Annual Report Summary is unaudited and does not conform to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and governmental reporting standards and does not include component units of the County. This Report is presented as a means of increasing transparency and public confidence in County Government through easier, more user-friendly financial reporting. Above all else this Report is designed to help taxpayers better understand how their tax dollars are being utilized. Readers desiring more detailed financial information can obtain the full, 167 page, CAFR on the Controller’s website at www.co.lancaster.pa.us/132/Controllers- Office or call 717-299-8262. I hope that you find this report interesting and informative. Sincerely, Brian K. Hurter, CPA Lancaster County Controller On May 10, 1729, Lancaster County became the fourth county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

817 Broadway Building

DESIGNATION REPORT 817 Broadway Building Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 512 Commission 817 Broadway Building LP-2614 June 11, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT 817 Broadway Building LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 817 Broadway (aka 817-819 Broadway, 48-54 East 12th Street) LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE 817 Broadway is a 14-story store-and-loft building designed by the prominent American architect George B. Post. Constructed in 1895- 98, this well-preserved Renaissance Revival- style structure represents the type of high-rise development that occurred on Broadway, south of Union Square, in the last decade of the 19th century. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 512 Commission 817 Broadway Building LP-2614 June 11, 2019 817 Broadway, 1905 Irving Underhill, Museum of the City of New York LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, General Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Diana Chapin Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire REPORT BY Michael Goldblum Matthew A. Postal, Research Department John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy EDITED BY Adi Shamir-Baron Kate Lemos McHale PHOTOGRAPHS Sarah Moses Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 512 Commission 817 Broadway Building LP-2614 June 11, 2019 3 of 21 817 Broadway Building Deborah Glick, as well as from the Municipal Art Manhattan Society of New York and the Metropolitan -

New York City

U.S. PERFORMANCE DESTINATIONS: New York City The “Big Apple” moniker for New York City was coined by musicians and meant, ‘to play the big time.’ Vibrant and diverse, New York offers all popular music genres: blues, jazz, rock, hip-hop, classical, disco and punk! As a place that offers something for everyone, New York is also welcoming and warm amidst the hustle-bustle pace that defines it. New Yorkers sincerely want you to enjoy your choices and have a great day in this great city. PERFORMANCE OPPORTUNITIES • Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade • Holley Plaza in Washington Square Park • St. Patrick’s Day Parade • Trump Tower • Veterans Day Parade • South Street Seaport • Carnegie Hall • St. Paul’s Chapel • Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts • New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade • Riverside Church • Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park • Southstreet Seaport Marketplace • Church of the Blessed Sacrament • St. Bartholomew’s Church • Flight Deck of the USS Intrepid • The Cathedral of St. John the Divine • St. George Theatre • St. Patrick’s Cathedral • Mason Hall • Statue of Liberty • Symphony Space • United Nations • Gerald W. Lynch Theater • St. Malachy’s Church • Center for the Arts • Band of Pride Tribute • Grace Church • Broadway Workshops • St. Joseph’s Catholic Church • Church of St. Paul the Apostle • St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church ADDITIONAL ATTRACTIONS • Workshop Opportunities • Manhattan TV & Movie Tour • New York Philharmonic • Metropolitan Museum of Art • Philharmonic Academy Jr. • Museum of Natural History • Broadway Workshops • NBC Studios • Broadway Shows • 9/11 Memorial Plaza • The Cathedral of St. John the Divine • Radio City Music Hall • Central Park • Rockefeller Center • Chinatown • Statue of Liberty • Little Italy • Times Square • Circle Line Cruise • Top of the Rock • 5th Avenue • United Nations • Empire State Building • Chelsea Piers Field House • Lincoln Center • Museum of Modern Art Travel planners for the finest bands, choirs and orchestras in the world. -

Partial Inventory to the Episcopal Diocese of Lexington Records, 1829-2012

Partial inventory to the Episcopal Diocese of Lexington records, 1829-2012 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on February 07, 2018. Describing Archives: A Content Standard University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center Special Collections Research Center University of Kentucky Libraries Margaret I. King Library Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0039 URL: https://libraries.uky.edu/SC Partial inventory to the Episcopal Diocese of Lexington records, 1829-2012 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 3 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Churches and Cathedrals ............................................................................................................................. 4 Priests and Bishops .................................................................................................................................. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report

Local Government fir1 Boundary Commission For England Report No. 52 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO.SZ LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund .Compton, GCB.KBE. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin,QC. - MEMBERS The Countess Of Albemarle,'DBE. Mr T C Benfield. Professor Michael Chisholm. Sir Andrew Wheatley,CBE. Mr P B Young, CBE. To the Rt Hon Roy Jenkins, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSAL FOR REVISED ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE CITY OF LANCASTER IN THE COUNTY OF LANCASHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the City of Lancaster in . accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and of Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that City. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 13 May 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the Lancaster City Council, copies of which were circulated to the Lancashire County Council, Parish Councils and Parish Meetings in the district, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from any interested bodies, 3- Lancaster City Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representa- tion for our consideration.