Far-Right Protests and Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TARIFE UND LINIENFAHRTEN Sächsische Dampfschiffahrt WXYZ

TARIFE UND LINIENFAHRTEN Sächsische Dampfschiffahrt WXYZ O N S Tarifzonengrenze Tarifzonengrenze Tarifzonengrenze Tarifzonengrenze Tarifzonengrenze Tarifzonengrenze W Kurort Rathen Felsenbühne, beeindru- Bad Schandau ckendes Basteimassiv, Nationalparkzentrum, Luftkurort Stadt Wehlen historische Kirnitzschtalbahn, Nationalpark Sächsische Schweiz Seußlitz Diesbar Radebeul Romantisches Karl-May-Museum, Spitzhaus, Elbstädtchen Barockschloss Malerisches Schloss Wackerbarth, Seußlitz mit Elbweindorf Pillnitz Prossen Lößnitzgrundbahn Schlossgarten Schloss Pillnitz Ausgangspunkt mit Schlosspark für Wanderungen Elbe Pirna Historische Altstadt, elbaufwärts → Stadtkirche St. Marien Richtung Tschechien ← elbabwärts Meißen Heidenau Richtung Hamburg Porzellan-Manufaktur, Dresden Barockgarten Blasewitz Albrechtsburg mit Dom, Frauenkirche, Großsedlitz, Königstein Klosterkirche, Altstadt Elbbrücke Schloss Weesenstein Semperoper, Weltbekannte Festung 240 Meter über der Elbe Zwinger „Blaues Wunder“, Bergbahnen, Elbschlösser TARIFE Erwachsene Kinder, Schüler JAHRESKARTEN und Studenten * Jahreskarte 455 YXX,XX € gültig auf allen Linienfahrten; personalisiert für Kurzstrecke bis =5 min \,eX € e,XX € Y Erwachsenen, YW Monate ab Ausstellungsdatum 4 Tarifzone YY,XX € \,XX € = Tarifzonen Yb,eX € YY,XX € Jahreskarte 455+4 YZX,XX € + Y beliebige Begleitperson ab C Tarifzonen WW,XX € Yc,XX € Jahreskarte \X,XX € gültig für Y Kind, Schüler, Student Rückfahrt in Verbindung mit Hinfahrt e,XX € f,XX € (Nachweis erforderlich) *Kinder (b-Yc Jahre), Schüler und Studenten -

KSB Celle KSB Harburg-Land Sportbund Heidekreis Inhaltsverzeichnis

anerkannt für ÜL C Ausbildung KSB Celle KSB Harburg-Land Sportbund Heidekreis Inhaltsverzeichnis Hier sind alle Fortbildungen zu finden, die über die Sportbünde Celle, Harburg-Land und Heidekreis angeboten werden. Mit einem „Klick“ auf den Titel werden sie direkt zur entsprechenden Ausschreibung geleitet Sprache lernen in Bewegung-Elementarbereich 4 Spiel und Sport im Schwarzlichtmodus 5 Fit mit digitalen Medien 6 Sport und Inklusion 7 Kräftigen und Dehnen 8 Fit mit Ausdauertraining /Blended learning Format 9 Starke Muskeln-wacher Geist - Kids 10 Spielekiste und trendige Bewegungsangebote 11 Das Deutsche Sportabzeichen 12 #Abenteuer?-Kooperative Abenteuerspiele und Erlebnispädagogik 13 Spiel- und Sport für kleine Leute 14 Alles eine Frage der Körperwahrnehmung! 15 Trainieren mit Elastiband 16 Mini-Sportabzeichen 17 Spiele mit Ball für Kinder im Vorschulalter 18 Rund um den Ball 19 Fitball-Trommeln 20 Einführung in das Beckenbodentraining 21 Der Strand wird zur Sportanlage 22 Inhaltsverzeichnis Stärkung des Selbstbewusstsein und Schutz vor Gewalt im Sport 23 Einführung in die Feldenkraismethode 24 Natur als Fitness-Studio 25 Bewegt in kleinen Räumen und an der frischen Luft 26 Übungsvielfalt 27 Stabil und standfest im Alter 28 Sport und Inklusion 29 Kinder stark machen 30 Ausbildung ÜL C 31 Information und Anmeldung 32 Legende: LQZ sind kostenfreie Fortbildungen für Lehrer, Erzieher und ÜL im Rahmen des Aktionsprogramms „Lernen braucht Bewegung“. Diese Fortbildung ist im C 50-Flexbereich der ÜL C-Ausbildung Breitensport anerkannt. ÜL B Diese Ausbildung ist für ÜL B Prävention anerkannt. Sprache lernen ….. 16.00-19.15 Uhr (4 LE) Celle Kostenfrei/ LQZ Dr. Bettina Arasin Nr.: 2/32/13870 … in Bewegung für den Elementarbereich. -

Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg RB38

Hamburg Buxtehude Cuxhaven HarHarr RB38 Winsen (Luhe) Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Bremen Suerhop Holm-Seppensen Büsenbachtal Handeloh RB38 Wintermoor HVV - Hamburger Verkehrsverbund Hannover Hbf – Soltau (Han) – Hamburg-Harburg Schneverdingen RB38 Wolterdingen (Han) Hamburg Buxtehude Soltau Nord Hamburg-Harburg Cuxhaven RB38 HarHarr Bus von Soltau Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Dorfmark Buchholz (Nordheide) Winsen (Luhe) Suerhop Lüneburg Bchhol Nordheide Uelzen Tarifausweitung des HVV ab 15.12.2019: Holm-Seppensen Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Bremen Der HVV wird größer und gilt künftig bis Uelzen, Büsenbachtal Suerhop Soltau und Cuxhaven. Handeloh Holm-Seppensen Hodenhagen Dadurch verändern sich die Zonen und Ringe RB38 Büsenbachtal NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wintermoor Handeloh RB38 auf der Strecke der RB38 an den Bahnhöfen Tages- und Zeit- Wolterdingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han). karten Ring E Schneverdingen RB38 Wintermoor NEU HVV-Einzel-, Wolterdingen (Han) Schwarmstedt • Verschiebung von Ring E nach F Tages- und Zeit- Schneverdingen karten Ring F Soltau Nord • Veränderung der Zonen-Nummern: Wolter- Lindwedel dingen, Soltau Nord und Soltau (Han) 838 -> Wolterdingen (Han) RB38 Soltau (Han) NEU HVV-Einzel-, Mellendorf 1028 Dorfmark Tages- und Zeit- Soltau Nord karten Ring F Bitte lassen Sie Ihre Zeitkarte ggf. in einer der Bus von Soltau Walsrode Bad Fallingbostel Hannover Sola Han nach Bispingen RB38 Servicestellen oder Ihr ProfiTicket bei Ihrem Dorfmark Flughafen Arbeitgeber ändern. Weitere Informationen un- Tarifinfos:Hodenhagen anenhaen -

Aktuelle Situation Im Landkreis Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge

Pressemitteilung Pressestelle Telefon: 03501 515-1110 E-Mail: [email protected] Telefax: 03501 515-81110 [email protected] Funk: 0151 11348804 Internet: www.landratsamt-pirna.de Datum: 06.01.2021 Nr.: 006 Corona-Virus: Aktuelle Situation im Landkreis Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge Stand 06.01.2021, 11:00 Uhr Allgemeine Informationen Das Robert-Koch-Institut weist nach seiner Berechnungsmethode aktuell den folgenden Inzidenzwert für den Landkreis aus: 340 (Stand 06.01.2021, 00:00 Uhr). Durch den Landkreis selbst wurden folgende Zahlen ermittelt: In den letzten sieben Tagen ist die Gesamtzahl der SARS-CoV-2 betroffenen Personen um 891 angewachsen. Bezogen auf 100.000 EW entspricht dies 363 . Do Fr Sa So Mo Di Mi Summe neue Positivfälle Inzidenz 31.12. 01.01. 02.01. 03.01. 04.01. 05.01. 06.01. der letzten 7 Tage 179 0 131 192 182 65 142 891 363 Die zu Grunde liegende Gesamteinwohnerzahl für den Landkreis beträgt 245.586 zum Stand 31.12.2019. Aktuell positiv getestete Personen: 896 (+ 111) Seit 02.03.2020 positiv getestete Personen: 10.837 (+ 142) Seit 02.03.2020 geheilte/aus Quarantäne entlassene Personen: 9.523 (+ 31) Seit 02.03.2020 verstorbene Personen: 418 (+ 0) Derzeit befinden sich 175 positiv auf SARS-CoV-2 getestete Personen im Landkreis in Krankenhäusern . Davon 32 intensiv versorgt und 143 auf Normalstation. Von den Covid-Betten in den Krankenhäusern im Landkreis sind keine Intensivbetten und 53 Normalbetten frei. (Quelle: CARUSshare Kollaborationsplattform des Uniklinikum Dresden, Stand 06.01.2021, 09:30 Uhr). Heute waren 331 Beprobungen vorgesehen. Hinweis zur Summe der neuen Positivfälle der letzten 7 Tage und der Anzahl der aktuell positiven Personen: Die Aufnahme eines positiven Falls durch das Gesundheitsamt in die o. -

Bahn Linie S1 Fahrpläne & Netzkarten

Bahn Linie S1 Fahrpläne & Netzkarten S1 Bad Schandau Im Website-Modus Anzeigen Die Bahn Linie S1 (Bad Schandau) hat 7 Routen (1) Bad Schandau: 04:17 - 23:17 (2) Dresden Hauptbahnhof: 00:07 - 08:17 (3) Dresden Hauptbahnhof: 00:17 - 18:04 (4) Meißen: 22:15 (5) Meißen Triebischtal: 04:30 - 23:15 (6) Pirna: 01:00 - 22:47 (7) Schöna: 04:29 - 20:47 Verwende Moovit, um die nächste Station der Bahn Linie S1 zu ƒnden und, um zu erfahren wann die nächste Bahn Linie S1 kommt. Richtung: Bad Schandau Bahn Linie S1 Fahrpläne 30 Haltestellen Abfahrzeiten in Richtung Bad Schandau LINIENPLAN ANZEIGEN Montag 04:17 - 23:17 Dienstag 04:17 - 23:17 Meißen Triebischtal Hirschbergstraße 30, Meißen Mittwoch 04:17 - 23:17 Meißen Altstadt Donnerstag 04:17 - 23:17 Neumarkt 5, Meißen Freitag 04:17 - 23:17 Meißen Samstag 04:17 - 23:17 Dresdner Straße 3, Meißen Sonntag 04:17 - 23:17 Neusörnewitz Coswig (Bei Dresden) Bahnhofstraße 2, Coswig Bahn Linie S1 Info Radebeul-Zitzschewig Richtung: Bad Schandau Coswiger Straße 12, Radebeul Stationen: 30 Fahrtdauer: 85 Min Radebeul-Kötzschenbroda Linien Informationen: Meißen Triebischtal, Meißen Bahnhofstraße 10, Radebeul Altstadt, Meißen, Neusörnewitz, Coswig (Bei Dresden), Radebeul-Zitzschewig, Radebeul- Radebeul-Weintraube Kötzschenbroda, Radebeul-Weintraube, Radebeul- Richard-Wagner-Straße 5, Radebeul Ost, Dresden-Trachau, Dresden-Pieschen, Dresden Bischofsplatz, Dresden-Neustadt, Dresden-Mitte, Radebeul-Ost Dresden Freiberger Straße, Dresden-Hauptbahnhof, Dresden-Strehlen, Dresden-Reick, Dresden-Dobritz, Dresden-Trachau -

Elbe Estuary Publishing Authorities

I Integrated M management plan P Elbe estuary Publishing authorities Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg Ministry of Urban Development and Environment http://www.hamburg.de/bsu The Federal State of Lower Saxony Lower Saxony Federal Institution for Water Management, Coasts and Conservation www.nlwkn.Niedersachsen.de The Federal State of Schleswig-Holstein Ministry of Agriculture, the Environment and Rural Areas http://www.schleswig-holstein.de/UmweltLandwirtschaft/DE/ UmweltLandwirtschaft_node.html Northern Directorate for Waterways and Shipping http://www.wsd-nord.wsv.de/ http://www.portal-tideelbe.de Hamburg Port Authority http://www.hamburg-port-authority.de/ http://www.tideelbe.de February 2012 Proposed quote Elbe estuary working group (2012): integrated management plan for the Elbe estuary http://www.natura2000-unterelbe.de/links-Gesamtplan.php Reference http://www.natura2000-unterelbe.de/links-Gesamtplan.php Reproduction is permitted provided the source is cited. Layout and graphics Kiel Institute for Landscape Ecology www.kifl.de Elbe water dropwort, Oenanthe conioides Integrated management plan Elbe estuary I M Elbe estuary P Brunsbüttel Glückstadt Cuxhaven Freiburg Introduction As a result of this international responsibility, the federal states worked together with the Federal Ad- The Elbe estuary – from Geeshacht, via Hamburg ministration for Waterways and Navigation and the to the mouth at the North Sea – is a lifeline for the Hamburg Port Authority to create a trans-state in- Hamburg metropolitan region, a flourishing cultural -

Ausschreibung OEM23 Final Englisch

Event organiser Society for Oberelbe-Marathon e. V. Head: Toralf Niese Am Dammberg 17, 01445 Radebeul Head of Organisation xperience sport & events Veranstaltungsagentur Head: Uwe Sonntag Marktweg 4, 01157 Dresden Fax: +49 (0) 3212.1364128 Hotline Mo-Fr: +49 (0)1577.1577139 E-Mail: [email protected] Auspices Klaus-Peter Hanke, Mayor of the city Pirna Michael Geisler, District administer of Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge Eligibility The 23. VVO Oberelbe-Marathon is officially measured and is organised according to the German Athletics Federation (DLV). Categories are also established according to the rules of the DLV. Routes/starting times/start places VVO Oberelbe marathon » 09:25 am Königstein, Elbe banks below the railway station Lichtenauer half marathon » 9:10 am Pirna, Glashüttenstraße, property of Minda KTSN GmbH (at road B 172). The start takes place in two waves. schulz aktiv 10-km-run » 9:10 am Dresden, restaurant Schillergarten close to bridge Blaues Wunder on the Elbe river banks Sachsenmilch 5-km-run » 9:10 am Dresden – bridge Waldschlößchenbrücke – at Elbe cycling route (Elberadweg) (Minimum 10 years of age or reaching this age in 2020) AOK PLUS 2,7-km-Minimarathon » NEW: 8:50 am Dresden, Finish area Heinz-Steyer-Stadium (start+finish) (Minimum 7 years of age or reaching this age in 2020) NEW 2020 – Bambini run (1/1000 marathon – ca. 420 m) » 8:35 am Dresden, Heinz-Steyer-stadium Every child that can run but is too young for the Mini marathon can participate. Registration is not necessary but recommended. All participants get a medal and a personal certificate. -

LES Sächsische Schweiz

LEADER-Region Sächsische Schweiz Zwischenevaluierung ELER Förderperiode 2014-2020 Anlagen – Auswertung Fragebögen Anlagen – Zwischenevaluierung LEADER-Region Sächsische Schweiz 2014 - 2020 3 1. AUSWERTUNG FRAGEBOGEN KOMMUNEN Anzahl Befragungsteilnehmer: 12 (von 23) K 1. Übersicht der Einwohnerzahlen nach Ortsteilen am 30.06.2018 Gemeinde/Stadt Ortsteil Einwohner Fläche in ha Fläche in km² Einwohner/km² Bahretal Borna 181 391,0 3,91 46 Bahretal Friedrichswalde 518 444,0 4,44 117 Bahretal Gersdorf 431 690,3 6,90 62 Bahretal Göppersdorf + Wingendorf 212 918,5 9,18 23 Nentmannsdorf + Niedersei- Bahretal 509 743,5 7,44 68 dewitz Bahretal Ottendorf 362 465,0 4,65 78 Bahretal gesamt 2.213 3.652,3 36,52 61 Gohrisch Kurort Gohrisch 757 k.A. k.A. Gohrisch Cunnersdorf 404 k.A. Gohrisch Kleinhennersdorf 232 k.A. Gohrisch Papstdorf 469 Gohrisch gesamt 1.862 3.486,6 34,87 53 Heidenau gesamt 16.779 1.107,0 k.A. k.A. Königstein Königstein 1.611 k.A. Königstein Pfaffendorf 298 k.A. Königstein Leupoldishain 208 Königstein gesamt 2.117 2.704,5 27,04 78 Kurort Rathen gesamt 345 3,58 96 Pirna Birkwitz 766 230,0 2,30 333 Pirna Bonnewitz 241 230,0 2,30 105 Pirna Copitz 9.709 450,0 4,50 2.158 Pirna Cunnersdorf 144 50,0 0,50 288 Pirna Graupa 3.107 710,0 7,10 438 Pirna Jessen 1.089 190,0 1,90 573 Pirna Krietzschwitz 139 400,0 4,00 35 Pirna Liebethal 281 140,0 1,40 201 Pirna Mockethal 328 280,0 2,80 117 Pirna Niedervogelgesang 59 40,0 0,40 148 Pirna Neundorf 492 160,0 1,60 308 Pirna Obervogelgesang 82 50,0 0,50 164 Pirna Pirna 14.169 830,0 8,30 1707 Pirna Posta -

Zinnwald Lithium Project

Zinnwald Lithium Project Report on the Mineral Resource Prepared for Deutsche Lithium GmbH Am St. Niclas Schacht 13 09599 Freiberg Germany Effective date: 2018-09-30 Issue date: 2018-09-30 Zinnwald Lithium Project Report on the Mineral Resource Date and signature page According to NI 43-101 requirements the „Qualified Persons“ for this report are EurGeol. Dr. Wolf-Dietrich Bock and EurGeol. Kersten Kühn. The effective date of this report is 30 September 2018. ……………………………….. Signed on 30 September 2018 EurGeol. Dr. Wolf-Dietrich Bock Consulting Geologist ……………………………….. Signed on 30 September 2018 EurGeol. Kersten Kühn Mining Geologist Date: Page: 2018-09-30 2/219 Zinnwald Lithium Project Report on the Mineral Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Date and signature page .............................................................................................................. 2 1 Summary .......................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Property Description and Ownership ........................................................................ 14 1.2 Geology and mineralization ...................................................................................... 14 1.3 Exploration status .................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Resource estimates ................................................................................................. 16 1.5 Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................................................... -

Beunruhigende Prognose Demographischer Wandel Und Die Entwicklung Von Krebsneuerkrankungs Fallzahlen Im Land Und in Den Landkreisen Niedersachsens Bis 2030

intern Krebsneuerkrankungen Beunruhigende Prognose Demographischer Wandel und die Entwicklung von Krebsneuerkrankungs fallzahlen im Land und in den Landkreisen Niedersachsens bis 2030 ochrechnungen von Neuerkrankungsfallzahlen für tions- und Früherkennungsmaßnahmen und Verhaltensän- verschiedene bösartige Neubildungen in Niedersach - derungen in der Bevölkerung (z. B. Rauch- oder Impfverhal- sen und die Darstellung von Veränderungen bis zum ten) diese maßgeblich beeinflussen können. Die dargestell- hJahr 2030 auf Landkreisebene sollen dazu beitragen, den zu- ten Veränderungen der Fallzahlen bis 2030 beziehen sich im- künftigen medizinischen Versorgungsbedarf im Land besser mer auf das Basisjahr 2008 und sind ausschließlich auf die abschätzen zu können. Als Grundlage für die Berechnungen Bevölkerungsentwicklungen in den Kreisen und kreisfreien dienen die Bevölkerungsvorausschätzung des Landesbe- Städten zurückzuführen. Fälle, die dem EKN nur über To- triebs für Statistik und Kommunikationstechnologie Nieder- desbescheinigungen bekannt werden (sogenannte DCO-Fäl- sachsen sowie geschlechts- und altersklassenspezifische In- le, death certificate only), sind in der Inzidenz nicht berück- zidenzraten der Jahre 2005 bis 2009 in Niedersachsen. Sie sichtigt worden. Die Hochrechnungen sind daher eher kon- lassen auf eine deutliche Zunahme der Krebserkrankungen servativ einzustufen und unterschätzen vermutlich die zu er- in Niedersachsen bis zum Jahr 2030 schließen, die bei der wartenden Krebsneuerkrankungen. weiteren Gesundheitsplanung zu berücksichtigen -

Um-Maps---G.Pdf

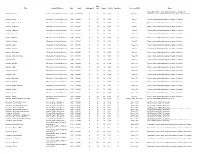

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Case Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Topography, towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gabon - Libreville Service Géographique de L'Armée 1935 1:1,000,000 N 35 10 G1-A F One sheet Cameroon, Gabon, all of Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé & Principe Gambia - Jinnak Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 1 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - N'Dungu Kebbe Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 2 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - No Kunda Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 4 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Farafenni Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 5 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kau-Ur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Bulgurk Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kudang Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Fass Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kuntaur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 8 Towns, roads, political -

Three New Test Regions in Ham- Burg's Real Digital Mobility

DB subsidiary ioki brings on-demand shuttles to rural areas: Three new test regions in Ham- burg’s real digital mobility lab Mobility analyses show new potentials of public transport • Winsen: 30 percent of journeys could be shifted from the road to climate-friendly public transport in the short term • Shuttles in Winsen, Ahrensburg and Stormarn about to start this year (Hamburg, August 21, 2020) By December 2020, public transport will be almost to the doorstep in three more districts in the greater Hamburg area. In Hamburg’s real digital mobility lab (“Reallabor Hamburg”), the Deutsche Bahn subsidiary ioki initially conducts mobility analyses for the three test regions Ahrensburg, Stormarn and Süderelbe. The most recent investigation of commuter flows and mobility behaviour in the Süderelbe region (south of the Elbe river), shows: the greatest potential for a flexible demand-re- sponsive transport service – without fixed timetables and stops – is found in the city of Winsen in the district of Harburg. In a second step, ioki is developing the platform for the operation of the on-demand shuttles, which will start in Ahrensburg and Stormarn as well as in Winsen this year. "Our analyses provide answers to the urgent future questions in mobility. How can we make public transport even more attractive and thus promote climate protection? With mobility analyses, we can calculate in advance where on-demand services will bring the greatest benefits. In Hamburg itself, we have already carried out several analyses and gained extensive practical experience. Now it is important that rural areas outside the Hanseatic city also benefit from new forms of mobility," says ioki CEO Dr.