Last Stop Ranchara Staged Reading Script (239.48

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent

latin artist la india sola album download torrent Latin artist la india sola album download torrent. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66ca8e0e4e9c0d3e • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. India. There at least two artist by the name of India, one from the United States and one from the United Kingdom. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. While known for her Salsa recordings, India started out recording Freestyle w/ her debut album Breaking Night in 1990 as well as lending her vocals to many house classics. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. -

La Salsa (Musical)

¿En qué piensan cuando leen la palabra - Salsa? ¿Piensan en lo que comemos con patatas fritas o tortillas? ¿O piensan en la mùsica y el baile? ¿Qué es la Salsa? Salsa es un estilo de música latinoamericana que surgió en Nueva York como resultado del choque de la música afrocaribeña traída por puertoriqueños, cubanos, colombianos, venezolanos, panameños y dominicanos, con el Jazz y el Rock de los norteamericanos. Desde ese entonces, vive deambulando de isla en isla, de país a país, incrementando de tal manera, su riqueza de elementos. Es asi que la Salsa no es una moda pasajera, sinó una corriente musical establecida, de alto valor artístico y gran significado sociocultural: en ella no existen barreras de clase ni de edad. ¿Quienes son los artistas de la Salsa? Celia Cruz La que se va a volver la Reina de la Salsa nació en 1924. Desde niña, al nacer su talento se atreve a cantar en unas fiestas escolares o de barrio, luego en unos concursos radiofónicos. Notaron su talento y entonces empezó una carrera bajo los consejos aclarados de uno de sus profesores. Asi fue que en el 1950, pudo imponerse como cantante en uno de los grupos más famosos de La Havana : la Sonora Matancera. Con este grupo de leyenda fue con quien recorrió toda América Latina durante quinze años, dejando mientras tanto en Cuba su experienca revolucionaria hasta que se instale en 1960 en los Estados Unidos. Hasta ahora, va a guardar una nostalgia de su país, que a menudo se podrá sentir en sus textos y intrevistas. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

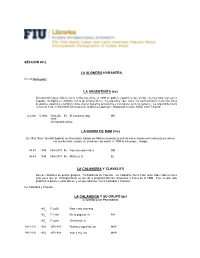

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Playbill 0911.Indd

umass fine arts center CENTER SERIES 2008–2009 1 2 3 4 playbill 1 Latin Fest featuring La India 09/20/08 2 Dave Pietro, Chakra Suite 10/03/08 3 Shakespeare & Company, Hamlet 10/08/08 4 Lura 10/09/08 DtCokeYoga8.5x11.qxp 5/17/07 11:30 AM Page 1 DC-07-M-3214 Yoga Class 8.5” x 11” YOGACLASS ©2007The Coca-Cola Company. Diet Coke and the Dynamic Ribbon are registered trademarks The of Coca-Cola Company. We’ve mastered the fine art of health care. Whether you need a family doctor or a physician specialist, in our region it’s Baystate Medical Practices that takes center stage in providing quality and excellence. From Greenfield to East Longmeadow, from young children to seniors, from coughs and colds to highly sophisticated surgery — we’ve got the talent and experience it takes to be the best. Visit us at www.baystatehealth.com/bmp Supporting The Community We Live In Helps Create a Better World For All Of Us Allen Davis, CFP® and The Davis Group Are Proud Supporters of the Fine Arts Center! The work we do with our clients enables them to share their assets with their families, loved ones, and the causes they support. But we also help clients share their growing knowledge and information about their financial position in useful and appropriate ways in order to empower and motivate those around them. Sharing is not limited to sharing material things; it’s also about sharing one’s personal and family legacy. It’s about passing along what matters most — during life, and after. -

(46000) Latinas in Popular Performance: from Celia to Selena

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN DEPARTMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O STUDIES SPRING 2021 MAS 315 (40640) AND WGS 301 (46000) LATINAS IN POPULAR PERFORMANCE: FROM CELIA TO SELENA MONDAYS AND WEDNESDAYS FROM 10:00 TO 11:30 AM. (SYNCHRONOUS) INTERNET (CANVAS / ZOOM) PROFESSOR: LAURA G. GUTIÉRREZ EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE PHONE: 471-3543 OFFICE HOURS: ON ZOOM OFFICE HOURS: MONDAYS AND WEDNESDAYS FROM 3:30-4:30 PM & BY APPOINTMENT Land Acknowledgment (I) We would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on Indigenous land. Moreover, (I) We would like to acknowledge and pay our respects to the Carrizo & Comecrudo, Coahuiltecan, Caddo, Tonkawa, Comanche, Lipan Apache, Alabama-Coushatta, Kickapoo, Tigua Pueblo, and all the American Indian and Indigenous Peoples and communities who have been or have become a part of these lands and territories in Texas, here on Turtle Island. Course Description: While this course’s title suggest that the span of the class material covered will begin with a visual cultural analysis of Celia Cruz, the Queen of Salsa, and will end with Selena, the Queen of Tejano, these two figures only conceptually bookend the ideas that will be explored during the semester. This class will begin by sampling a number of performances of Latinas in popular cultural texts to get lay the ground for the analytical and conceptual frameworks that we will be exploring during the semester. First of all, in a workshop format, we will learn to analyze cultural texts that are visual and movement-based. We will, for example, learn to write performance and visual analysis by collectively learning and putting into practice vocabulary connected to the body in movement, space(s), and visual references (from color to specific ethnic tropes). -

MESA REDONDA La India Catalina ¿Un Símbolo Apto De Cartagena? ______

303 ____________________________________________________________________ MESA REDONDA La India Catalina ¿Un símbolo apto de Cartagena? ____________________________________________________________________ PARTICIPANTES Gerardo Ardila Elizabeth Cunin Rafael Ortiz Moderador: Alberto Abello Vives Alberto Abello Vives: Una niña nacida en Zamba, hoy Galera Zamba, fue raptada por Diego de Nicuesa en su incursión a la Costa del hoy Caribe Colombiano entre 1509 y 1511. Los españoles la bautizaron con el nombre de Catalina y la llevaron esclavizada a Santo Domingo. Allí fue criada por religiosas que le enseñaron la lengua castellana y la religión católica. Se convirtió en traductora y fue enviada a Gaira, provincia de Santa Marta. De allí fue recogida por Pedro de Heredia, quien la trajo a Cartagena en 1533. Fue con Pedro de Heredia a Zamba y allí se volvió a encontrar con su gente. Dijeron los españoles que en ese entonces Catalina vestía a la usanza española, de zapatillas y abanico. Fue la guía de Heredia y su traductora. Terminó acusándolo en su primer juicio de residencia. Casi 500 años después Catalina está viva en Ursúa, la novela de William Ospina publicada en el 2005. Hay en ese libro unas líneas dedicadas al retorno de esta muchacha legendaria a Galerazamba. El novelista la llama Catalina de Galera Zamba. En el año 2006, Hernán Urbina publica Las huellas de la india Catalina, un ensayo de 140 páginas en el que reconstruye la ruta de sus viajes desde que fuera secuestrada por Diego de Nicuesa, hasta cuando desapareció en las sombras de la historia. El autor se preocupa por su personalidad y sus sentimientos. Se pregunta si 304 ¿Logró Catalina ser feliz? Aporta también a la memoria los recuerdos de quienes hoy son responsables de una Catalina hecha estatua, de pie, empinada, incansable en aquella glorieta cartagenera que hizo famosa. -

Tu Amor Es Mi Fortuna

ASI SON LOS HOMBRES (AGUA BELLA) TU AMOR ES MI FORTUNA (AGUA MARINA) YOU OUTHTA KNOW (ALANIS MORRISETTE) NI TU NI NADIE (ALASKA DINARAMA) QUE ME QUITAN LO BAILAO (ALBITA) ETERNAMENTE BELLA (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) MIRALO MIRALO (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) REINA DE CORAZONES (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) BESITO DE COCO/CARAMELO (ALQUIMIA) BERENICE (AMPARO SANDINO) CAMINOS DEL CORAZON (AMPARO SANDINO) GOZATE LA VIDA (AMPARO SANDINO) VALERIE (AMY WHITEHOUSE) BANDIDO (ANA BARBARA) LO QUE SON LAS COSAS (ANAIS) TANTO LA QUERIA (ANDY & LUCAS) PAYASO (ANDY MONTAÑEZ) SE FUE Y ME DEJO (ANDY MONTAÑEZ) ANAISAOCO (ANGEL CANALES) BOMBA CARAMBOMBA (ANGEL CANALES) LEJOS DE TI (ANGEL CANALES) SANDRA (ANGEL CANALES) SOLO SE QUE TIENE NOMBRE DE MUJER (ANGEL CANALES) QUE BOMBOM (ANTHONY CRUZ) GAROTA DE IPANEMA (ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM) CERVECERO (ARMONIA 10) EL SOL NO REGRESARA (ARMONIA 10) HASTA LAS 6 AM (ARMONIA 10) LA CARTA FINAL (ARMONIA 10) LA RICOTONA (ARMONIA 10) SURENA (ARTURO SANDOVAL) LA CURITA (AVENTURA) BESELA YA (BACILOS) PASOS DE GIGANTE (BACILOS) LA TREMENDA (BAMBOLEO) YA NO ME HACES FALTA (BAMBOLEO) YO NO ME PAREZCO A NADIE (BAMBOLEO) EL PILLO (BAMBOLEO) IF NOT NOW THEN WHEN (BASIA) LAGRIMAS NEGRAS (BEBO VALDES) EL AGUA (BOBBY VALENTIN) TE VOY A REGALAR MI AMOR (BONGA) RABIA (BRENDA STAR) DANCING IN THE DARK (BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN) DOS GARDENIAS(BOLERO) (BUENA VISTA S. CLUB) LA CHOLA CADERONA (BUSH Y LOS MAGNIFICOS) MI BOMBOM (CABAS) DE QUE ME SIRVE QUERERTE (CALLE CIEGA) UNA VEZ MAS (CALLE CIEGA) COMO SI NADA (CAMILO AZUQUITA) COLGANDO EN TUS MANOS (CARLOS BAUTE) LA MARAVILLA (CARLOS VIVES) TORO MATA (CELIA CRUZ) BEMBA COLORA (CELIA CRUZ) KIMBARA (CELIA CRUZ) LA VIDA ES UN CARNAVAL (CELIA CRUZ) NO ME HABLES DE AMOR(BOLERO) (CELIA CRUZ) UD ABUSO (CELIA CRUZ) VIEJA LUNA(BOLERO) (CELIA CRUZ) YO SI SOY VENENO (CELIA CRUZ) SALVAJE (CESAR FLORES) PROCURA (CHICHI PERALTA) ESTOY AQUÍ (CHIKY SALSA) MAMBO INFLUENCIADO (CHUCHO VALDES) EL VIENTO ME DA (COMBO DEL AYER) ME ENAMORO DE TI (COMBO LOCO) GOZA LA VIDA (CONJ. -

1 Societas, Vol. 17, N° 2

Societas, Vol. 17, N° 2 1 AUTORIDADES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE PANAMÁ Dr. Gustavo García de Paredes Rector Dr. Justo Medrano Vicerrector Académico Dr. Juan Antonio Gómez Herrera Vicerrector de Investigación y Postgrado Dr. Nicolás Jerome Vicerrector Administrativo Ing. Eldis Barnes Vicerrector de Asuntos Estudiantiles Dra. María del Carmen Terrientes de Benavides Vicerrectora de Extensión Dr. Miguel Ángel Candanedo Secretario General Mgter. Luis Posso Director General de los Centros Regionales Universitarios 2 Societas, Vol. 17, N° 2 SOCIETAS Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanísticas Universidad de Panamá Vol. 17 - N°2 Publicación de la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado Societas, Vol. 17, N° 2 3 Societas Revista editada por la Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado de la Universidad de Panamá, cuyo fin es contribuir al avance del conocimiento de las Ciencias Sociales y Humanísticas. Se publica en la modalidad de un volumen anual que se divide en dos números. EDITOR: Dr. ALFREDO FIGUEROA NAVARRO Diagramación: Editorial Universitaria Carlos Manuel Gasteazoro - Universidad de Panamá. Impreso en Panamá / 300 ejemplares. Vol. 17 - N°2 - Diciembre de 2015 ISSN 1560-0408 Los artículos aparecidos en Societas se encuentran indizados en LATINDEX. CONSEJO EDITORIAL Mgtra. MARCELA CAMARGO Dr. VÍCTOR VEGA REYES Directora Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Políticas, Centro de Investigaciones, Universidad de Panamá, Facultad de Humanidades, Panamá Universidad de Panamá, Panamá Arq. MAGELA CABRERA Facultad de Arquitectura, Mgter. JORGE CASTILLO Universidad de Panamá, Facultad de Economía, Panamá Universidad de Panamá, Panamá Dr. STANLEY HECKADON MORENO Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Mgter. ERNESTO BOTELLO Tropicales, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Panamá Universidad de Panamá, Panamá Mgter. -

![1857-12-02, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9732/1857-12-02-p-3509732.webp)

1857-12-02, [P ]

ALiroat* Will raw, Light—•l,'.!.Vl,Ot T. mtww.1 Gov. Walki escapfi President to < I Ki ™_-. *ork' -v qasstlsa settled apaa term; kaaerakk aad aa* tful tragedy occurred at Port Jeffer- fairs at lengtk. l to; A lllPy*fobber)rlMMBsmitied on WTOklWi, to«i. •hitih, slur ftuuting alaag the centre ot th«. tbe ConMitu- Ttr- r --.f.i rm occupied ia thees. tUMory to all pardesTand sett!^imrs«ima*sTi£ & Q^y; tii^MaM, ia fetavday vt *«-M«r*< S, mill two wosktto moraing, by which Area pereene loot their Uvea road for some diraoee, was caught by his keep Uouil Coaventioi>na ttot reiki *i&t#tite o'clock of tke P. M. of tbe 14th. Sbe haa 71 yiitg ln tfij stresin, while tf^^Spuin'waa ab- 1 ly, aa a varybody sappoaed. How did it tara ers *hi(s ia (he aft of tearing a lad whounforta- 1 gumeiiu ol 'insei. The Pariah Will •itMT. aad a fourth waa seriously, pwkape fatally, in Instrument tit tke peoplSt Tka 4lttjtet*bed pksMiigfer* affcd ttfftVQOO in specie and a very {sent on shore. The cabin wa« emen d and two > oatf Tke Democratic pan v, led Lj Doaglas, aad nately creased tke animal's path. Tbe tiger, undoubtedly the most important -t jJV jured. At half-past seven o'clock in the morn* Gents., tkoogk dMiWtag ridlcally, parted frieada krrge aad valuable cargo of French merehaa- casks of doabloOos, valued at fHVXMi were sto disregarding ibe public good aad cariag aatkiag wkiek ia aal; 18 months oUt, tint of large else* amoont of property involved, the peculiar .J Itfi *•|« (ral«r«<ikw War* ing Mrs. -

Read the Introduction (Pdf)

Introduction Salsa in New York ugust 1992. Hector Lavoe is putting together a new band, making a comeback after a self-imposed hiatus during which he fought for his life, tried to beat addiction, and, as we would find out later, battled A1 AIDS. A rehearsal is scheduled for 7 p.m. in the basement of the Boys and Girls Harbor School (“Boys Harbor”), located in El Barrio (Spanish Harlem) on the corner of East 104th Street and 5th Avenue, a favorite spot for salsa bands to work out new arrangements. Why? Cheap rates, an out-of-the-way place that fans don’t know about, and a location in the most historically sig- nificant neighborhood for Latin music in New York City. In fact, just blocks from Boys Harbor is where it all began back in the 1930s: Machito, Tito Puente, Eddie and Charlie Palmieri, everyone lived there. Most salsa musi- cians do not live in the neighborhood anymore, although many teach Latin music to kids and novices at the Harbor’s after-school program, one of the few places where 15 bucks will get you a lesson with Tito Puente’s bongocero. Rehearsal begins just shy of 8 p.m. It was delayed while several musicians copped in the neighborhood. Copped what? Blow, perico, cocaine. Other mu- sicians just straggled in late with no explanation, but no real need: No one complains about the late start. It’s par for the course. Regardless of their tardi- ness, everyone who enters the room makes his rounds greeting everyone else. -

Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UT Digital Repository The Report committee for Anna Monroe Teague Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: ___________________________________ John Turci-Escobar, Supervisor ___________________________________ Robin Moore Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music by Anna Monroe Teague, B.M. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music The University of Texas at Austin May, 2015 Abstract Charting Rhythmic Energy in Nuyorican Salsa Music Anna Monroe Teague, M.Music The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 SUPERVISOR: John Turci-Escobar There are many statements from members of the salsa community (including scholars, musicians, and dancers) that mention the presence, gaining, or waning of metaphorical rhythmic energy. Since many salsa sources employ ethnomusicological, biographical, or performance approaches, however, any text briefly mentioning musical energy would not require validation for energetic claims. Adopting a music-theoretical approach, this report focuses on how the rhythm section contributes to energy perceptions. Syncopation—or metrical dissonance—underlies metaphorical energy in salsa. This syncopation appears in individual rhythmic patterns and layered polyrhythms called rhythmic profiles, which correspond to energy-level associations with particular instruments and formal sections. Additionally, rhythmic changes on the larger formal iii scale as well as on a smaller motivic scale can account for the perception of changes in energy levels. This report presents a method for analyzing metrical dissonance in Nuyorican salsa, after reviewing the relevant theoretical tools by Harald Krebs and Yonatan Malin and surveying the core features of this subgenre. -

World of Sound Catalog Wholesale List

WORLD OF SOUND CATALOG WHOLESALE LIST ORGANIZED IN ORDER BASED ON RECORD LABEL Smithsonian Folkways Recordings ◊ Collector Records ◊ Consignment ◊ Cook Records ◊ Dyer-Bennet Records ◊ Fast Folk Musical Magazine ◊ Folkways Records ◊ Monitor Records ◊ Minority Owned Record Enterprises (M.O.R.E.) ◊ Paredon Records ◊ Smithsonian Folkways Special Series Published 3/3/2011 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings CATALOG NO. ALBUM TITLE ALBUM ARTIST YEAR SFW40000 Folkways: The Original Vision Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly 2005 SFW40002 Musics of the Soviet Union Various Artists 1989 SFW40003 Happy Woman Blues Lucinda Williams 1990 SFW40004 Country Songs, Old and New The Country Gentlemen 1990 SFW40005 Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson at Folk City Jean Ritchie and Doc Watson 1990 SFW40006 Cajun Social Music Various Artists 1990 SFW40007 Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs Woody Guthrie 1989 SFW40008 Broadside Tapes 1 Phil Ochs 1989 SFW40009 Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes Elizabeth Cotten 1989 SFW40010 Lead Belly Sings Folk Songs Lead Belly 1989 SFW40011 Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry Sing Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee 1990 SFW40012 The Doc Watson Family The Doc Watson Family 1990 SFW40013 Family Songs and Stories from the North Carolina Mountains Doug and Jack Wallin 1995 SFW40014 Puerto Rican Music in Hawaii Various Artists 1989 SFW40015 Hawaiian Drum Dance Chants: Sounds of Power in Time Various Artists 1989 Musics of Hawai'i: Anthology of Hawaiian Music - Special Festival SFW40016 Various Artists 1989 Edition SFW40017 Tuva: Voices from the Center of Asia Various Artists 1990 SFW40018 Darling Corey/Goofing-Off Suite Pete Seeger 1993 SFW40019 Lightnin' Hopkins Lightnin' Hopkins 1990 SFW40020 Mountain Music of Peru, Vol.