Master Document Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample File This Page Intentionally Left Blank

The Comic Art of War Sample file This page intentionally left blank Sample file The Comic Art of War A Critical Study of Military Cartoons, 1805–2014, with a Guide to Artists Christina M. Knopf Sample file McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Knopf, Christina M., 1980– The comic art of war : a critical study of military cartoons, 1805–2014, with a guide to artists / Christina M. Knopf. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-9835-2 (softcover : acid free paper) ISBN 978-1-4766-2081-7 (ebook) ♾ 1. War—Caricatures and cartoons. 2. Soldiers—Caricatures and cartoons. 3. MilitarySample life—Caricatures file and cartoons. I. Title. U20.K58 2015 355.0022'2—dc23 2015024596 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2015 Christina M. Knopf. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: COMPANY DIS-MISSED! by Abian A. “Wally” Wallgren which appeared in the final World War I issue of Stars and Stripes (vol. 2 no. 19: p. 7) on June 18, 1919. It features the artist dismissing his models, or characters, from duty at the end of the war. Printed in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments It is said that writing is a solitary activity. -

"Turtleneck and Chain" Fails to Impress Eager Fans

PAGE THE STAR MAY 16, 2011 ENTERTAINMENT 7 ''Cultures of Resistance'' "Turtleneck and Chain" raises a\Nareness for· fails to impress eager fans Sonoma State students' KAITLII', ZtTELLI made of materials that .most Ameri Editorial Asst. cans would throw in the trash. There are two generations that hav·e no edu Iara Lee's heartbreaking docu cation and no values. mentary "Cultures of Resistance," "I wanted to see if it was a boy or shown in Darwin Hall on May 12, girl," said one man when telling how raises awareness of world conflicts he tore an unborn baby out.of wom being fought by people through both an's stomach. · violent and artistic measures to keep And the movie goes on, with their cultures and ways of life alive. more gut wrenching problems that Filmmaker Lee and her producer most Americans don't even know are George Gunn conceived "Cultures of happening. Resistance" in 2003, right before the One · woman walked out of the Iraq war. The film was later named audience, others were silently crying. the Best Documentary at the Tiburon But the saddest part of the event was 2011 Film Festival. many audience member's complacen ''People were being killed and cy. The room was maybe one-third nobody cared. I started looking for full and at least five people were on small gestures-ordinary people that their cell phones, occasionally glanc were relatable," said Lee in the dis ing up while these horror stories were cussion following the screening of being told and then looking right back Courtesy// Kaboommagazine.com the documentary. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent

latin artist la india sola album download torrent Latin artist la india sola album download torrent. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66ca8e0e4e9c0d3e • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. India. There at least two artist by the name of India, one from the United States and one from the United Kingdom. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. While known for her Salsa recordings, India started out recording Freestyle w/ her debut album Breaking Night in 1990 as well as lending her vocals to many house classics. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. -

La Salsa (Musical)

¿En qué piensan cuando leen la palabra - Salsa? ¿Piensan en lo que comemos con patatas fritas o tortillas? ¿O piensan en la mùsica y el baile? ¿Qué es la Salsa? Salsa es un estilo de música latinoamericana que surgió en Nueva York como resultado del choque de la música afrocaribeña traída por puertoriqueños, cubanos, colombianos, venezolanos, panameños y dominicanos, con el Jazz y el Rock de los norteamericanos. Desde ese entonces, vive deambulando de isla en isla, de país a país, incrementando de tal manera, su riqueza de elementos. Es asi que la Salsa no es una moda pasajera, sinó una corriente musical establecida, de alto valor artístico y gran significado sociocultural: en ella no existen barreras de clase ni de edad. ¿Quienes son los artistas de la Salsa? Celia Cruz La que se va a volver la Reina de la Salsa nació en 1924. Desde niña, al nacer su talento se atreve a cantar en unas fiestas escolares o de barrio, luego en unos concursos radiofónicos. Notaron su talento y entonces empezó una carrera bajo los consejos aclarados de uno de sus profesores. Asi fue que en el 1950, pudo imponerse como cantante en uno de los grupos más famosos de La Havana : la Sonora Matancera. Con este grupo de leyenda fue con quien recorrió toda América Latina durante quinze años, dejando mientras tanto en Cuba su experienca revolucionaria hasta que se instale en 1960 en los Estados Unidos. Hasta ahora, va a guardar una nostalgia de su país, que a menudo se podrá sentir en sus textos y intrevistas. -

2015 Review from the Director

2015 REVIEW From the Director I am often asked, “Where is the Center going?” Looking of our Smithsonian Capital Campaign goal of $4 million, forward to 2016, I am happy to share in the following and we plan to build on our cultural sustainability and pages several accomplishments from the past year that fundraising efforts in 2016. illustrate where we’re headed next. This year we invested in strengthening our research and At the top of my list of priorities for 2016 is strengthening outreach by publishing an astonishing 56 pieces, growing our two signatures programs, the Smithsonian Folklife our reputation for serious scholarship and expanding Festival and Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. For the our audience. We plan to expand on this work by hiring Festival, we are transitioning to a new funding model a curator with expertise in digital and emerging media and reorganizing to ensure the event enters its fiftieth and Latino culture in 2016. We also improved care for our anniversary year on a solid foundation. We embarked on collections by hiring two new staff archivists and stabilizing a search for a new director and curator of Smithsonian access to funds for our Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Folkways as Daniel Sheehy prepares for retirement, Collections. We are investing in deeper public engagement and we look forward to welcoming a new leader to the by embarking on a strategic communications planning Smithsonian’s nonprofit record label this year. While 2015 project, staffing communications work, and expanding our was a year of transition for both programs, I am confident digital offerings. -

Public Involvement Plan

Defense Environmental Restoration Program for Formerly Used Defense Sites Military Munitions Response Program Property Number I02PR0068 CULEBRA - Puerto Rico Public Involvement Plan Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville District August 18, 2005 Culebra – Puerto Rico Defense Environmental Restoration Program Contents Abbreviations & Acronyms .............................................................................................................. iii 1.0 Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 Site Description ............................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Location and Physical Description ............................................................................ 2-1 2.2 Culebra and the United States Military ..................................................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Historic Overview ............................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.2.2 Historic Milestones ......................................................................................................................... 2-2 2.2.3 Previous USACE Involvement ........................................................................................................ 2-3 3.0 Community Background ............................................................................................... 3-1 3.1 -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

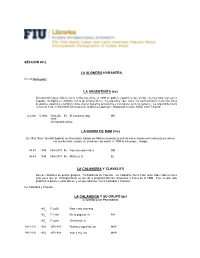

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

The Butt of the Joke? Laughter and Potency in the Becoming of Good Soldiers

The Butt of the Joke? The Butt of the Joke? Laughter and Potency in the Becoming of Good Soldiers Beate Sløk-Andersen Copenhagen Business School Denmark Abstract In the Danish military, laughter plays a key role in the process of becoming a good soldier. Along with the strictness of hierarchy and discipline, a perhaps surprisingly widespread use of humor is essential in the social interaction, as the author observed during a participatory fieldwork among conscripted soldiers in the army. Unfolding the wider context and affective flows in this use of humor, however, the article suggests that the humorous tune (Ahmed 2014a) that is established among the soldiers concurrently has severe consequences as it not only polices soldiers’ sexuality and ‘wrong’ ways for men to be close, but also entangles in the ‘making’ of good, potent soldiers. Humor is therefore argued to be a very serious matter that can cast soldiers as either insiders or outsiders to the military profession. Keywords: military, humor, attunement, affects, military service, potency, sexuality uring a four-month-long participatory fieldwork amongst soldiers serving in the Danish army, I experienced how laughter permeated everyday life and caused momentary breaks from the seriousness that came with being Dembedded in a quite hierarchal structure. Even the sergeants who were supposed to discipline the young soldiers were keen on lightening the atmosphere by telling jokes or encouraging others to do so. Humor appeared to make military service more fun: it lightened the mood and supported social bonds among soldiers which also made the tough times more bearable. However, I also observed how humor took part in ‘making’ of military professionals; how seemingly innocent comments or actions that were “just a joke” took part in establishing otherwise unspoken limitations and norms for how to be a good soldier. -

1 Eugenio Maria De Hostos Community College / CUNY

Eugenio Maria de Hostos Community College / CUNY Humanities Department Visual & Performing Arts Unit Academic Program Review Fall 2016 Second Draft Academic Program Mission Statement The Visual & Performing Arts Unit fosters and maintains the history and practice of all aspects of artistic endeavor in the College and the community. Through its curriculum, members of the College community and other members of the urban community explore, interpret, and apply the artistic practices that lead to a better understanding of themselves, their environment, and their roles in society. Description of the Unit The VPA Unit is the largest unit of the Humanities Department. It serves approximately 1,125 students from all majors at Hostos every semester. With courses as far ranging as painting and drawing, art history, public speaking, acting, music, and photography, students can pursue many possible creative paths. Those who elect to earn credits in the visual and performing arts will find a variety of approaches to learning that include lecture and studio based classes as well as workshops that allow for the exploration of extracurricular interests or even for the development of career centered skill sets vital to the pursuit of employment opportunities. The successful completion of courses in the arts are a useful and, in many cases, essential basis for study in other disciplines. They are also a valuable source for personal development. Students interested in planning a concentration in the visual and performing arts are advised to consult with the Visual and Performing Arts Coordinator. The Media Design Programs were originally housed in the VPA Unit, but operate as a separate unit due to the considerable growth of students and courses. -

José Gabriel Muñoz Interview Transcript

Raíces Digital Archive Oral History Transcript José Gabriel Muñoz - Cuatrista October 20, 2019 [0:11] José Gabriel Muñoz: My name is José Gabriel Muñoz and I play the Puerto Rican cuatro. It’s used mostly for the folkloric music of Puerto Rico. [0:20] I grew up listening to the music in my household. My dad would always play the music. I was born in Puerto Rico so I had those roots of the music and the culture was always in my family. And my dad would always play the music so growing up, I was always listening to it, it was always basically a part of me. [41:00] But when I was about fourteen years old I saw someone play it in front of me for the first time, and it happened to be a young man, my same age, about fourteen-thirteen, fourteen, at the time, and that’s when it became palpable and real to me. Up until then it was listening to eight-tracks and cassettes, you know, the old guard of the music, as I would call it. [1:03] And so, many young people, as myself at the time, would interpret that as just music for old people, music of my grandfathers, of my older uncles and such. It wasn’t the here and now, hip type music. Up until I watched this young man play, right in front of me, and it became alive to me, and from that moment on is where the interest grew. [1:32] Nicole Wines: Can you talk a little bit about the instrument itself? [1:38] JGM: The instrument comes from the lute family, it is my understanding.