Redalyc.Memorializing La Lupe and Lavoe: Singing Vulgarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Flores, Juan. “Creolité in the 'Hood: Diaspora As Source and Challenge

Centro Journal City University of New York. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños [email protected] ISSN: 1538-6279 LATINOAMERICANISTAS 2004 Juan Flores CREOLITÉ IN THE ‘HOOD: DIASPORA AS SOURCE AND CHALLENGE Centro Journal, fall, año/vol. XVI, número 002 City University of New York. Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños New York, Latinoamericanistas pp. 282-293 Flores(v12).qxd 3/1/05 7:55 AM Page 282 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Creolité in the ‘Hood: Diaspora as Source and Challenge* JUAN FLORES ABSTRACT This article highlights the role of the Puerto Rican community in New York as the social base for the creation of Latin music of the 1960s and 1970s known as salsa, as well as its relation to the island. As implied in the subtitle, the argument is advanced that Caribbean diaspora communities need to be seen as sources of creative cultural innovation rather than as mere repositories or extensions of expressive traditions in the geographical homelands, and furthermore as a potential challenge to the assumptions of cultural authenticity typical of traditional conceptions of national culture. It is further contended that a transnational and pan- Caribbean framework is needed for a full understanding of these complex new conditions of musical migration and interaction. [Key words: salsa, transnationalism, authenticity, cultural innovation, New York music, musical migration] [ 283 ] Flores(v12).qxd 3/1/05 7:55 AM Page 284 he flight attendant let out became the basis of a widely publicized other final stop of the commute, -

Ismael Rivera: El Eterno Sonero Mayor

• Ismael Rivera, ca. 1982 Ismael Rivera: el eterno Sonero mayor Ismael Rivera, o eterno Ismael Rivera: the eternal Sonero mayor Sonero mayor Robert Téllez Moreno* DOI: 10.30578/nomadas.n45a13 El artículo presenta un recorrido biográico y musical en torno al cantante y compositor puer- torriqueño Ismael Rivera, “El Sonero Mayor”. De la mano del artista, el texto provee claves para entender el surgimiento de la salsa como género musical, así como muestra algunos hitos en la historia del género. Concluye que la intervención de Rivera en la escena musical isleña y continental constituyó una revolución que dispersó las fronteras sociales de la exclusión cultu- ral. Por su parte, su estilo interpretativo se caracteriza por un inmenso sentimiento popular y una gran capacidad de improvisación. Palabras clave: Ismael Rivera, Puerto Rico, música popular, clave de son, salsa, racismo. O artigo apresenta um recorrido biográico e musical acerca do cantor e compositor Ismael Ri- vera, “El sonero mayor”, nascido em Puerto Rico. Da mão do artista, o texto oferece chaves para compreender o surgimento da salsa como gênero musical, ao tempo que mostra alguns marcos da história desse gênero. O autor conclui que a intervenção de Rivera no cenário musical da ilha e do continente constituiu uma revolução que dissipou as fronteiras sociais da exclusão cultural. O estilo interpretativo de Rivera é caraterizado por um enorme sentimento popular e por uma grande capacidade de improvisação. Palavras-chave: Ismael Rivera, Puerto Rico, música popular, clave de son, salsa, racismo. * Director y realizador del programa This article shows a biographical and musical overview of the Puerto Rican singer and son- Conversando la salsa de la Radio gwriter, Ismael Rivera, “El Sonero Mayor”. -

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

Mario Ortiz Jr

Hom e | Features | Columns | Hit Parades | Reviews | Calendar | News | Contacts | Shopping | E-Back Issues NOVEMBER 2009 ISSUE FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the home of Latin Beat Magazine Digital! After publishing Latin Beat Magazine for 19 years in both print and online, Yvette and I have decided to continue pursuing our passion for Latin music with a digital version only. Latin Beat Magazine will continue its coverage of Latin music through monthly in-depth articles, informative Streaming Music columns, concert and CD reviews, and extensive news and information for everyone. Access to Somos Son www.lbmo.com or www.latinbeatmagazine.com (Latin Beat Magazine Online) is free for a limited Bilongo time only. Windows Media Quicktime Your events and new music submissions are welcome and encouraged by emailing to: [email protected]. The Estrada Brothers Latin beat is number one in the world of authentic Latin music. For advertising opportunities in Mr. Ray lbmo.com, call (310) 516-6767 or request advertising information at Windows Media [email protected]. Quicktime Back issues are still in print! Please order thru the Shopping section! Manny Silvera Bassed in America This issue of Latin Beat Magazine Volume 19, Number 9, November 2009, is our annual "Special Windows Media Percussion/Drum Issue", which celebrates "National Drum Month" throughout North America. Our Quicktime featured artist this month is Puerto Rican percussionist/bandleader Richie Flores. In addition, also featured are Poncho Sanchez (who's enjoying the release of his latest production Psychedelic Blues), and trumpeter/bandleader Mario Ortiz Jr. (who has one of the hottest salsa Bobby Matos productions of the year). -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

CBS International's Study

BEFORE THE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL WASHINGTON, D.C. In the Matter of ) ) 1984 Juke-Box Royalty ) Docket No. Distribution Proceedings ) SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENT PURSUANT TO 37 C.F.R. SECTION 305.4 Asociacion de Compositores y Editores de Musica Latino- americana ("ACEMLA"), having duly filed a claim of entitlement pursuant to 37 C.F.R. Sections 305.2, 305.3 and having filed a statement pursuant to 37 C.F.R. Section 305.4 on November 5, 1985, submits this supplemental statement and documentation on November 5th filing. 1. In Paragraph 4 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement, I ACEMLA cited a study undertaken by Discos CBS International as cited in the publication "Music Video Retailer" in January 1983. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is the article concerning Discos CBS International's study. 2. In Paragraph 5 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement, an article entitled "Spanish Speaking Market on the Move" from the January 1983 issue of "Music Video Retailer" was also cited. This article is attached as Exhibit 2. 3. Paragraph 7 of ACEMLA's November 5th Statement noted that "throughout 1984 a significant number of hits whose copy rights were owned or administered by ACEMLA appeared in trade charts both in 45 rpm or LP form. These trade charts reflect the major songs in the United States Hispanic market." 4. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 are hit Latin record charts from the publication "Canales", published in New York City, for the months of January 1984 through November 1984. The circled numbers next to the title and the circled titles in- dicate titles that are in in ACEMLA's catalogue. -

Almanaque Marc Emery. June, 2009

CONTENIDOS 2CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009. Jan Susler. 6ENERO. 11 LAS FASES DE LA LUNA EN LA AGRICULTURA TRADICIONAL. José Rivera Rojas. 15 FEBRERO. 19ALIMÉNTATE CON NUESTROS SUPER ALIMENTOS SILVESTRES. María Benedetti. 25MARZO. 30EL SUEÑO DE DON PACO.Minga de Cielos. 37 ABRIL. 42EXTRACTO DE SON CIMARRÓN POR ADOLFINA VILLANUEVA. Edwin Reyes. 46PREDICCIONES Y CONSEJOS. Elsie La Gitana. 49MAYO. 53PUERTO RICO: PARAÍSO TROPICAL DE LOS TRANSGÉNICOS. Carmelo Ruiz Marrero. 57JUNIO. 62PLAZA LAS AMÉRICAS: ENSAMBLAJE DE IMÁGENES EN EL TIEMPO. Javier Román. 69JULIO. 74MACHUCA Y EL MAR. Dulce Yanomamo. 84LISTADO DE ORGANIZACIONES AMBIENTALES EN PUERTO RICO. 87AGOSTO. 1 92SOBRE LA PARTERÍA. ENTREVISTA A VANESSA CALDARI. Carolina Caycedo. 101SEPTIEMBRE. 105USANDO LAS PLANTAS Y LA NATURALEZA PARA POTENCIAR LA REVOLUCIÓN CONSCIENTE DEL PUEBLO.Marc Emery. 110OCTUBRE. 114LA GRAN MENTIRA. ENTREVISTA AL MOVIMIENTO INDÍGENA JÍBARO BORICUA.Canela Romero. 126NOVIEMBRE. 131MAPA CULTURAL DE 81 SOCIEDADES. Inglehart y Welzel. 132INFORMACIÓN Y ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES DE PUERTO RICO. 136DICIEMBRE. 141LISTADO DE FERIAS, FESTIVALES, FIESTAS, BIENALES Y EVENTOS CULTURALES Y FOLKLÓRICOS EN PUERTO RICO Y EL MUNDO. 145CALENDARIO LUNAR Y DÍAS FESTIVOS PARA PUERTO RICO. 146ÍNDICE DE IMÁGENES. 148MAPA DE PUERTO RICO EN BLANCO PARA ANOTACIONES. 2 3 CÁLCULOS ASTRONÓMICOS PARA LOS PRESOS Febrero: Memorias torrenciales inundarán la isla en el primer aniversario de la captura de POLÍTICOS PUERTORRIQUEÑOS EN EL AÑO 2009 Avelino González Claudio, y en el tercer aniversario de que el FBI allanara los hogares y oficinas de independentistas y agrediera a periodistas que cubrían los eventos. Preparado por Jan Susler exclusivamente para el Almanaque Marc Emery ___________________________________________________________________ Marzo: Se predice lluvias de cartas en apoyo a la petición de libertad bajo palabra por parte de Carlos Alberto Torres. -

Rumba Rhythms, Salsa Sound

MUSIC MILESTONES AMERICAN MS, RUMBA RHYTH ND BOSSA NOVA, A THE SALSA SOUND MATT DOEDEN This Page Left Blank Intentionally MUSIC MILESTONES AMERICAN MS, RUMBA RHYTH ND BOSSA NOVA, A HE SALSA SOUND T MATT DOEDEN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS MINNEAPOLIS NOTE TO READERS: some songs and music videos by artists discussed in this book contain language and images that readers may consider offensive. Copyright © 2013 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review. Twenty-First Century Books A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. 241 First Avenue North Minneapolis, MN 55401 U.S.A. Website address: www.lernerbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Doeden, Matt. American Latin music : rumba rhythms, bossa nova, and the salsa sound / by Matt Doeden. p. cm. — (American music milestones) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–7613–4505–3 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—United States—Latin American influences. 2. Dance music—Latin America—History and criticism. 3. Music— Latin America—History and criticism. 4. Musicians—Latin America. 5. Salsa (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3477.D64 2013 781.64089’68073—dc23 2012002074 Manufactured in the United States of America 1 – CG – 7/15/12 Building the Latin Sound www 5 Latin Fusions www 21 Sensations www 33 www The Latin Explosion 43 Glossary w 56 Source Notes w 61 Timeline w 57 Selected Bibliography w 61 Mini Bios w 58 Further Reading, w Websites, Latin Must-Haves 59 and Films w 62 w Major Awards 60 Index w 63 BUILDING THE Pitbull L E F T, Rodrigo y Gabriela R IG H T, and Shakira FAR RIGHT are some of the big gest names in modern Latin music. -

Jennifer Lopez's Career: J. Lows and Highs Tuesday, April 20, 2010 4:57

Norwalk Reflector Front Page 1 of 3 NorwalkReflector.com Front Article Jennifer Lopez’s career: J. lows and highs By Frank Lovece - Newsday (MCT) Tuesday, April 20, 2010 4:57 PM EDT Dancer-singer-actress Jennifer Lopez hadn’t danced, sung or acted much since taking time off to have kids — though since People reportedly paid her and husband Marc Anthony $4 million to $6 million in 2008 to parade them on a magazine cover, it’s ironically the most successful thing she’s done in years. Before her hiatus, she had a string of flop movies, a single that didn’t crack the Billboard Top 10, and an American Music Award downshift from favorite pop/rock female artist in 2003 to the more niche favorite Latin artist in 2007. Oh, and her record label just dropped her. Now the 40-year-old star is calibrating a comeback that has included guest appearances on “How I Met Your Mother,” “Saturday Night Live” and reportedly an upcoming episode of “Glee,” all to support her romantic comedy “The Back-Up Plan,” opening Friday. And in the meantime, with businesses encompassing everything from music to movies to a clothing line to a Cuban restaurant, she’s the ninth-richest woman in entertainment, says Forbes magazine, which in 2007 estimated her net worth at $110 million. So, shed no tears for her career. Dancer-singer-actress or waitress-writer-dog walker, we all have our highs and lows. Here are hers: _Fledgling 1986-1993 After her film debut as a teen in the 1986 indie drama “My Little Girl,” she went on to gain a toehold as a professional dancer. -

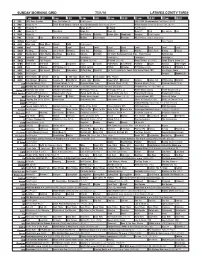

Sunday Morning Grid 7/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program 2016 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å 2016 Ricoh Women’s British Open Championship Final Round. (N) Å Action Sports From Long Beach, Calif. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Pregame MLS Soccer: Timbers at Sporting 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Mom Mkver Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program El Chavo (N) (TVG) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fútbol Central Fútbol Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl On the Psychiatrist’s Couch With Daniel Amen, MD San Diego: Above 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Haywire (R) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J.