Istanbul Technical University Institute of Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Program Booklet

Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival Fourth Year July 12 – 30, 2016 University of South Florida, School of Music 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL The family of Steinway pianos at USF was made possible by the kind assistance of the Music Gallery in Clearwater, Florida Rebecca Penneys Ray Gottlieb, O.D., Ph.D President & Artistic Director Vice President Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano wishes to give special thanks to: The University of South Florida for such warm hospitality, USF administration and staff for wonderful support and assistance, Glenn Suyker, Notable Works Inc., for piano tuning and maintenance, Christy Sallee and Emily Macias, for photos and video of each special moment, and All the devoted piano lovers, volunteers, and donors who make RPPF possible. The Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival is tuition-free for all students. It is supported entirely by charitable tax-deductible gifts made to Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano Incorporated, a non-profit 501(c)(3). Your gifts build our future. Donate on-line: http://rebeccapenneyspianofestival.org/ Mail a check: Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano P.O. Box 66054 St Pete Beach, Florida 33736 Become an RPPF volunteer, partner, or sponsor Email: [email protected] 2 FACULTY PHOTOS Seán Duggan Tannis Gibson Christopher Eunmi Ko Harding Yong Hi Moon Roberta Rust Thomas Omri Shimron Schumacher D mitri Shteinberg Richard Shuster Mayron Tsong Blanca Uribe Benjamin Warsaw Tabitha Columbare Yueun Kim Kevin Wu Head Coordinator Assistant Assistant 3 STUDENT PHOTOS (CONTINUED ON P. 51) Rolando Mijung Hannah Matthew Alejandro An Bossner Calderon Haewon David Natalie David Cho Cordóba-Hernández Doughty Furney David Oksana Noah Hsiu-Jung Gatchel Germain Hardaway Hou Jingning Minhee Jinsung Jason Renny Huang Kang Kim Kim Ko 4 CALENDAR OF EVENTS University of South Florida – School of Music Concerts and Masterclasses are FREE and open to the public Donations accepted at the door Festival Soirée Concerts – Barness Recital Hall, see p. -

Programm-Heft

Das Präsidium wünscht Ihnen eine interessante und gelungene Tagung Prof. Dr. Peter Nenniger (Präsident Prof. Dr. Karl Jug (Vizepräsident) Irmtraud Bast Freifrau von Humboldt-Dachroeden (Schatzmeisterin) Prof. Dr. Dr. Dagmar Hülsenberg (Koordinatorin des Akad. Rates) PD Dr. Udo von der Burg (Schriftführer) Georg Freiherr von Humboldt-Dachroeden (Geschäftsführer) Das Schloss wurde unter der Regentschaft der Kurfürsten Karl Philipp und Karl Theodor in drei Bauperioden zwischen 1720 und 1760 erbaut und war Residenz der Kurfürsten von der Pfalz von 1720 bis 1777. Titelbild: Der Wasserturm ist das Wahrzeichen Mannheims. Erbaut 1886-1889 nach Plänen von dem Stuttgarter Architekten Gustav Halmhuber, der auch am Bau des Berliner Reichstags mitwirkte. Als Herzstück der zentralen Trinkwasserversorgung geplant und gebaut, diente er nach dem Bau des höher gelegenen Wasserturms im nördl. Stadtteil Luzenberg 1909 noch bis zum Jahr 2000 als Reservehochbehälter. Er ist 60 m hoch, hat einen Durchmesser von 19 m und fasst 2000 cbm Wasser. Nach dem 2. Weltkrieg wurde er 1963 originalgetreu rekonstruiert. Das Dach des Turmes bekrönt eine 3,50 m hohe Statue der Amphitrite, der Gattin des Meeresgottes Poseidon. Auch der weitere Bildschmuck und die Figuren am kleinen und am großen Becken nehmen diese Thematik auf: Wasser ist Leben und – speziell für Mannheim – die Grundlage für Schifffahrt und Handel. Mit seinem Ensemble aus Turm, Garten, Wasserbecken und der angrenzenden Festhalle sowie der Kunsthalle gilt der Friedrichsplatz als eine der schönsten Jugendstilanlagen Deutschlands. Freitag Vortagung im Tagungshotel 02.10.2015 Maritim Parkhotel Mannheim mit paralleler Tagung von: 13:00-15:00 Akademischer Rat und Junge Humboldtianer optional 15:15-16:30 Geführter Stadtrundgang. -

Van Cott Information Services (Incorporated 1990) Offers Books

Clarinet Catalog 9a Van Cott Information Services, Inc. 02/08/08 presents Member: Clarinet Books, Music, CDs and More! International Clarinet Association This catalog includes clarinet books, CDs, videos, Music Minus One and other play-along CDs, woodwind books, and general music books. We are happy to accept Purchase Orders from University Music Departments, Libraries and Bookstores (see Ordering Informa- tion). We also have a full line of flute, saxophone, oboe, and bassoon books, videos and CDs. You may order online, by fax, or phone. To order or for the latest information visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com. Bindings: HB: Hard Bound, PB: Perfect Bound (paperback with square spine), SS: Saddle Stitch (paper, folded and stapled), SB: Spiral Bound (plastic or metal). Shipping: Heavy item, US Media Mail shipping charges based on weight. Free US Media Mail shipping if ordered with another item. Price and availability subject to change. C001. Altissimo Register: A Partial Approach by Paul Drushler. SHALL-u-mo Publications, SB, 30 pages. The au- Table of Contents thor's premise is that the best choices for specific fingerings Clarinet Books ....................................................................... 1 for certain passages can usually be determined with know- Single Reed Books and Videos................................................ 6 ledge of partials. Diagrams and comments on altissimo finger- ings using the fifth partial and above. Clarinet Music ....................................................................... 6 Excerpts and Parts ........................................................ 6 14.95 Master Classes .............................................................. 8 C058. The Art of Clarinet Playing by Keith Stein. Summy- Birchard, PB, 80 pages. A highly regarded introduction to the Methods ........................................................................ 8 technical aspects of clarinet playing. Subjects covered include Music ......................................................................... -

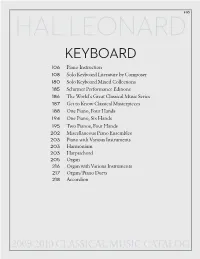

Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 105 HAL LEONARD105 KEYBOARD

76164 4 Classical_Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 105 HAL LEONARD105 KEYBOARD 106 Piano Instruction 108 Solo Keyboard Literature by Composer 180 Solo Keyboard Mixed Collections 185 Schirmer Performance Editions 186 The World’s Great Classical Music Series 187 Get to Know Classical Masterpieces 188 One Piano, Four Hands 194 One Piano, Six Hands 195 Two Pianos, Four Hands 202 Miscellaneous Piano Ensembles 203 Piano with Various Instruments 203 Harmonium 203 Harpsichord 205 Organ 216 Organ with Various Instruments 217 Organ/Piano Duets 218 Accordion 2009-2010 CLASSICAL MUSIC CATALOG 76164 4 Classical_Keyboard: 6/18/09 3:51 PM Page 106 106 PIANO INSTRUCTION ______49005413 Easy Baroque Piano Music (Emonts) PIANO INSTRUCTION Schott ED5096 ...........................................................$13.95 ______49005116 Easy Piano Pieces from Bach’s Sons to Beethoven ADAMS, BRET (ed. Emonts) Schott ED4747 .....................................$13.95 ______50006170 12 Primer Theory Papers ______49005117 Easy Romantic Piano Music – Volume 1 (ed. Emonts) Schirmer SG2566 ..........................................................$4.95 Schott ED4748 ...........................................................$13.95 BENNER, LORA ______49007882 Easy Romantic Piano Music – Volume 2 (ed. Emonts) Schott ED8277 ...........................................................$13.95 ______50330220 Theory for Piano Students Book 1 From Bartók to Stravinsky Easy Modern Piano Pieces Schirmer ED2511 ..........................................................$9.95 ______49005136 -

Fall 2005 Publication Agreement Number 40016225 Provincial Newsle� Er B.C

fall 2005 Publication Agreement Number 40016225 Provincial Newsle� er B.C. Registered Music Teachers’ Association B.C. Pianist tied for 1st Place in the Piano Competition at CF Conference rom the moment we arrived in Calgary, we knew we were in for Fa great week. Th e smiling face of our “Conference Chauff eur” greeted us at the airport and after a scenic ride, we arrived at Cascade Hall at the University of Calgary. After getting settled into our accommodations, we attended the opening ceremonies where Convener Linda Kundert-Stoll introduced us to the fi rst of many “Yippees” and “Yahoos” identifying Calgary as the home of the world-famous Stampede. Th at evening, L - R: Patricia Frehlich - (Incoming CF Pres), Katherine Chi, native of Calgary and Marnie Hauschildt, Robert Biswas - 1st place winners of CF Competition, Victoria Warwick - (outgoing CF Pres). internationally known pianist, presented the opening musical event, a sterling recital of Mozart, Hetu and Schubert. (Katherine generously stepped in when the original artist, Roberto Plano was unable to perform.) After examining the schedule for the coming week, we quickly realized that we had to make some choices, as there was more than one event scheduled at the same time. Our Convention Bag contained an MYC yellow highlighter -- now we knew why! Many of us chose to attend the class by Seymour Bernstein, famous pianist and author from New York, who gave an entertaining master class where his musical wisdom was clearly displayed. Lunch was provided by RCM Examinations where the dynamic duo of Levene & Lopinski offi cially launched the new Piano Pedagogy program. -

Achtsamer Umgang Mit Ressourcen Und Miteinander – Gestern Und Heute

Achtsamer Umgang mit Ressourcen und miteinander – gestern und heute Abhandlungen der Humboldt-Gesellschaft für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Bildung e.V. Band 37, September 2016 Achtsamer Umgang mit Ressourcen und miteinander – gestern und heute Abhandlungen der Humboldt-Gesellschaft für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Bildung e.V. Band 37, September 2016 Achtsamer Umgang mit Ressourcen und miteinander – gestern und heute mit Beiträgen von Klaus-Dieter Barbknecht, Inge Brose-Müller, Udo von der Burg, Ulrich Groß, Gert Helms, Wolfgang Hinrichs, Ursula Klein, Erhard Meyer-Galow, Peter Nenniger, Ulrich Stottmeister und Joachim Ulbricht Humboldt-Gesellschaft für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Bildung e.V. Die Beiträge geben ausschließlich die Meinung der Verfasser wieder. %LEOLRJUDÀVFKH,QIRUPDWLRQHQGHU'HXWVFKHQ1DWLRQDOELEOLRWKHN Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der 'HXWVFKHQ1DWLRQDOELEOLRJUDÀHGHWDLOOLHUWHELEOLRJUDÀVFKH'DWHQVLQGLP,QWHUQHW über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Humboldt-Gesellschaft für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Bildung e.V., Mannheim ISBN: 978-3-940456-72-4 Copyright 2016 by Humboldt-Gesellschaft für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Bildung e.V. Sitz Mannheim Jede Art der Vervielfältigung und Wiedergabe ist untersagt. Redaktion: Prof. Dr. Dr. Dagmar Hülsenberg, 98693 Ilmenau Layout, Druck und Verlag: TZ-Verlag & Print GmbH, 64380 Roßdorf www.edition-tz.de www.tz-verlag.de ,QKDOW Anschriften der Autoren ......................................................................................6 Vorwort................................................................................................................7 -

Genuin Katalog 07.Indd

CATALOGUE 2007 Dear music lover, Verehrter Musikliebhaber, we are delighted and proud to present our fourth mit großer Freude und auch ein wenig Stolz prä- GENUIN catalogue! Since we introduced the la- sentieren wir Ihnen hiermit den nunmehr vierten bel in 2004, the catalogue has grown from a small GENUIN-Katalog. Seit der offi ziellen Labelein- leafl et with just 14 CDs to this 36-page booklet führung im Jahre 2004 ist er von einem kleinen featuring almost 100 CDs. Flyer mit gerade einmal 14 CDs auf dieses 36 Sei- As sound engineers committed to classical ten starke und knapp 100 CDs umfassende Heft music, we courageously took the risk of founding angewachsen. GENUIN, placing a new label in a market con- Damals, noch als junge Klassik-Tonmeister, sidered dead. Today, we have a practically global gingen wir engagiert und mutig das Wagnis ein, in presence and up to four publications per month, einem totgesagten Markt ein neues Label zu plat- and our reputation is growing steadily. zieren. Heute sind wir mit Vertrieben in Europa, We are particularly happy that our CDs are not Asien und den USA praktisch weltweit vertreten, only selling well, but that we are reaching more mit bis zu vier Veröffentlichungen im Monat und and more music afi cionados and receiving en- stetig wachsendem Bekanntheitsgrad. thusiastic responses from professionals and non- Dabei freut uns besonders, dass wir mit un- professionals alike. Last year, we won numer- serem Label nicht nur Verkaufserfolge feiern, ous prizes from print and internet media as well sondern auch immer mehr Musikbegeisterte er- as the French Diapason d’Or Award for our CD reichen und von professioneller wie auch nicht- “The Last Recital” with David Oistrakh and Paul professioneller Seite beste Resonanz erhalten. -

2003 Winter 1St "Yasuko Fukuda Scholarship Audition"

of 2003 Winter Piano Teachers' National Association of Japan,Incorporated by the Japanese Government 1st "Yasuko Fukuda Scholarship Audition" held to encourage young talents The First Yasuko Fukuda Scholarship Audition was held in Tokyo on August 27th-29th . It was established after the Founder’s will to encourage young promising pianists to study abroad. There was a document pre-selection and 9 pianists aged 14 to 18 went on to the audition. The 3 days audition was consisted of private lessons and the concert, which is a reasonable way to evaluate their potential talents. Jury members were Dr.Paul Pollei (U.S.), Awarding ceremony at Yasuko Fukuda Audition(8/29). (from left)Special committee members(Mr.Seikoh Prof. Bruno Rigutto(France), and Prof.Andrei Pisarev(Russia). Fukuda, Prof.Yuko Ninomiya, Prof.Mieko Harimoto), Sekimoto, and jury members(Prof.Bruno Rigutto,Prof. Each of the 9 candidates took lessons by 3 jurors respectively Andrei Pisarev, Dr.Paul Pollei) and every lesson was filled with excitement. On the final day, they played 30 minutes program in front of the public, whose performances were good enough to regard as the international standard. Among them, Mr.Shohei Sekimoto(18) won the "Yasuko Fukuda Prize" and received 1million yen scholarship. His passion and romanticism was fully expressed in Rachmanninov Sonata No.2. Mr. Hibiki Tamura(16) received the 2nd best prize with half-million yen scholarship. The Liszt and Mendelssohn’s Sonata were artistically and expressively performed. Sekimoto and Tamura has took part in the PTNA Piano Competition from their childhood, and PTNA witnessed their talents steadily grown up in the past years. -

102. Tagung Dieser Zeit Fanden U.A

Prof. Dr. Christian von Holst, Stuttgart Konzertmeisterin Gertrud Schilde, München wurde 1941 in Danzig geboren. 1960 Abitur. Zunächst Studium der Theater- Studium der Violine und Kammermusik in München, Chicago, Salzburg und Sydney wissenschaften, dann der Kunstgeschichte, im Nebenfach Klassische (u.a. bei Ana Chumachenco, Shmuel Ashkenasi, Vermeer-Quartett und Uzi Wiesel. Archäologie in München, Florenz und Berlin. An der FU Berlin promovierte er Diplom „mit Auszeichnung” und Meisterklasse in München, Meisterkurse u.a. bei 1968 über Francesco Granacci als Maler (1469-1543). Von 1969 bis 1974 war er Herman Krebbers und Valerij Klimov, Stipendiatin der Yehudi-Menuhin-Stiftung und Stipendiat und Assistent am Kunsthistorischen Institut in Florenz. Dort kuratierte des Richard-Wagner-Verbandes. er auch 1971 seine erste Ausstellung von Künstlern der „Villa Romana“. Von Lehrauftrag für Violine und Kammermusik an der Hochschule für Musik und Theater 1975 bis 2006 an der Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, begann er als Referent für Kunst München, Leitung einer Masterclass am Nagoya College of Music in Japan. des 19. Jahrhunderts und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und wurde 1994 ihr Direktor. In Mitglied und Konzertmeisterin verschiedener Kammermusikensembles und 102. Tagung dieser Zeit fanden u.a. 1976 die Ausstellung „Gottlieb Schick, Ein Maler des Zusammenarbeit mit renommierten Regisseuren, Schauspielern und Schriftstellern. Klassizismus“ (mit Ulrike Gauss) und 1980 die Ausstellung „Dante–Vergil– Weltweite Konzerttätigkeit mit zahlreichen Einladungen zu bedeutenden der Geryon. Der 17. Höllengesang der Göttlichen Komödie in der bildenden Kunst“. Musikfestivals. Zahlreiche CD-, Rundfunk- und Fernsehaufnahmen. Preisträgerin bei Die Stadt Marbach verlieh ihm 1997 den Schillerpreis und 2007 wurde er (wie internationalen Wettbewerben. schon 1808 Goethe) zum "Chevalier dans l’Ordre de la Légion d’Honneur" HUMBOLDT-GESELLSCHAFT ernannt. -

PTNA News Letter 2005

Piano Teachers' National Association of Japan, Incorporated by the Japanese Government 1-15-1 Sugamo, Toshima-ku, Tokyo 170-8458, Japan PTNA Tel: +81-3-3944-1583 Fax:+81-3-3944-8838 [email protected] News Letter 2005 www.piano.or.jp/english New mission of PTNA is "School Kids" PTNA Prize Winners go to school classroom PTNA started "Classroom Concert Project" in June 2005. Selected pianists go to elementary schools to give concerts as a special music lesson. This is designed at one-classroom basis, not big auditoriums, so that pupils can easily communicate with pianists. They can feel free to listen and enjoy music around the piano, rather than sit in silence. Pianists are PTNA past prize winners, who have enthusiasm to play for school kids. Noriko Sato(27), the 2001 grand prize winner, is the one who agrees with this project. She appeared in the classroom of 4th grade(age 9-10) with a clarinettist. The "Why can you move your fingers so fast?" "What a beautiful music...!", "Oh, look at the inside of the piano! The mechanic is so complicated.." program was 45 min consisted of serious pieces and entertaining "Did you see the bottom? It sounds amazingly" ---Piano becomes friend of musics. What interested the kids most was her brilliant technique them. in Chopin Waltz, Impromptu, and "Immerkleiner" in which every decreasing and children part of the clarinet is taken away along with the music. Surprize have less opportunity and excitement came to their mind. to listen to the music On November 24th, one of the finalists of 15th Chopin with real sounds. -

American String Teacher February 2016 | Volume 66 | Number 1

AMERICAN STRING TEACHER February 2016 | Volume 66 | Number 1 l Guitar Forum: GarageBand Tutorial for Guitar Instructors l The Modern Harpist: Plays Well with Others l Want to Learn More About Fiddle Styles, Jazz Strings and Rock? plus: 2016 ASTA National Conference Preview Join us for friendship and fun in Tampa, Florida at the 2016 National Conference! www.astaweb.com | 3 4 | American String Teacher | February 2016 AMERICAN STRING TEACHER CONTENTS February 2016 | Volume 66 | Number 1 Features Music Degrees - Everything You Need to Know from 24 Application to Graduation Part 2 (of a 3-part series) – Auditions Navigating the college audition and admissions process is often fraught with anxiety for music students and their parents. by Hillary Herndon Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Participatory 28 Stratification in Public School Orchestras String music education in the United States is traditionally plagued by low student enrollment and high attrition rates. Exacerbating the crisis is a fundamental paradigm, which at best accepts inequality of opportunity, and at worst encourages it. by Angela Ammerman Guitar Forum: GarageBand Tutorial for Guitar Instructors 32 Contemporary guitar instructors can find musical assistance from their computers that will function well whether teaching privately or in a classroom. by Bill Purse The Modern Harpist: Plays Well with Others 36 Today’s harpists must be well-rounded and acquire proficiency in many areas of performing. by Gretchen Van Hoesen Want to Learn More About Fiddle Styles, Jazz Strings and Rock? Eclectic styles music in its many forms is taught at music camps throughout the USA and Canada during 40 the summer. -

G. Henleverlag

General Catalogue 2013/2014 Urtext Editions Study Scores Facsimiles Complete Editions Books Gifts All prices are in U.S. dollars. G. HenleVerlag 1066191 HenleGuts.indd 1 4/12/13 3:26 PM Wörterverzeichnis Vocabulary Vocabulaire Abteilung . series . série Anhang . appendix . appendice Aufführungsmaterial . performing material . matériel d’orchestre Ausgabe . edition . édition Auswahl . selection . sélection Auswahlbände . collections . recueils Band . volume . volume Blasinstrument . wind instrument . instrument à vent Broschur . paper bound . broché Cembalo . harpsichord . clavecin Dur . major . majeur Einbanddecke . binder . couverture Einzelausgabe . single edition . édition séparée erleichtert . facilitated . facilité Erstausgabe . first edition . première édition Fagott . bassoon . basson Fassung . version . version (ohne) Fingersatz . (without) fingering . (sans) doigté Ganzleinen . cloth binding . relié (pleine toile) gebunden . bound . relié Generalbass . figured bass, thorough bass . basse chiffrée, basse continue – Aussetzung . – realization . – réalisation Gesang . song, singing . chant Handschrift . manuscript . manuscrit Heft . book . cahier Herausgeber . editor . éditeur herausgegeben . edited by . édité par hoch . high . élevé Inhalt . contents . contenu Kammermusik . chamber music . musique de chambre Klavierauszug . piano reduction . réduction pour piano Kritischer Bericht . critical commentary . compte rendu critique leicht . easy . facile leihweise . for rent . en location Messe . mass . messe mittel . middle . moyen