The Race for the Mexican Presidency Begins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexico: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report | Freedom Hous

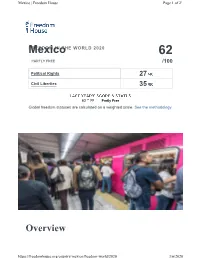

FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2021 Mexico 61 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 27 /40 Civil Liberties 34 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 62 /100 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview Mexico has been an electoral democracy since 2000, and alternation in power between parties is routine at both the federal and state levels. However, the country suffers from severe rule of law deficits that limit full citizen enjoyment of political rights and civil liberties. Violence perpetrated by organized criminals, corruption among government officials, human rights abuses by both state and nonstate actors, and rampant impunity are among the most visible of Mexico’s many governance challenges. Key Developments in 2020 • With over 125,000 deaths and 1.4 million cases, people in Mexico were severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government initially hid the virus’s true toll from the public, and the actual numbers of cases and deaths caused by the coronavirus are unknown. • In July, authorities identified the bone fragments of one of the 43 missing Guerrero students, further undermining stories about the controversial case told by the Peña Nieto administration. • Also in July, former head of the state oil company PEMEX Emilio Lozoya was implicated in several multimillion-dollar graft schemes involving other high- ranking former officials. Extradited from Spain, he testified against his former bosses and peers, including former presidents Calderón and Peña Nieto. • In December, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) named Mexico the most dangerous country in the world for members of the media. -

Mexico Preelection Assessment Legislative Elections Set for June 2021

Mexico Preelection assessment Legislative elections set for June 2021 Mexican citizens will take to the polls on June 6 to elect all 500 members of the Chamber of Deputies, as well as 15 governors and thousands of local positions. The vote is seen as a test of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s popularity and that of his National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). It will also determine whether he can retain control of the Chamber after his party secured a majority with the help of its coalition allies in the 2018 elections. The three main opposition parties, the National Action Party (PAN), the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD), have formed an unlikely and ideologically incongruous alliance known as Go for Mexico (Va por México) in an effort to wrench the majority away from the current left-wing populist government. The 2018 election was seen as a repudiation of the incumbent political establishment and was marred by unprecedented levels of election-related violence, as well as allegations of illegal campaign financing, vote buying, and the misuse of public funds. Paired with budget cuts to the National Electoral Institute (INE) and accusations that Obrador’s government has sought to lessen electoral oversight and roll back government transparency, these issues raise concern about the administration of the upcoming election. The COVID-19 crisis has further complicated the electoral environment, as the country finds itself with the world’s third-highest death toll. Mismanagement of the pandemic response sparked antigovernment protests in the months leading up to the election, which were further fueled by a recent economic recession, record-high homicide rates, and dissatisfaction with Obrador’s public comments on gender-based violence. -

Morena En El Sistema De Partidos En México: 2012-2018

Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 Juan Pablo Navarrete Vela Toluca, México • 2019 JL1298. M68 Navarrete Vela, Juan Pablo N321 Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 / Juan Pablo 2019 Navarrete Vela. — Toluca, México : Instituto Electoral del Estado de México, Centro de Formación y Documentación Electoral, 2019. XXXV, 373 p. : tablas. — (Serie Investigaciones Jurídicas y Político- Electorales). ISBN 978-607-9496-73-9 1. Partido Morena - Partido Político 2. Sistemas de partidos - México 3. López Obrador, Andrés Manuel 4. Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (México) 5. Partidos Políticos - México - Historia Esta investigación, para ser publicada, fue arbitrada y avalada por el sistema de pares académicos en la modalidad de doble ciego. Serie: Investigaciones Jurídicas y Político-Electorales. Primera edición, octubre de 2019. D. R. © Juan Pablo Navarrete Vela, 2019. D. R. © Instituto Electoral del Estado de México, 2019. Paseo Tollocan núm. 944, col. Santa Ana Tlapaltitlán, Toluca, México, C. P. 50160. www.ieem.org.mx Derechos reservados conforme a la ley ISBN 978-607-9496-73-9 ISBN de la versión electrónica 978-607-9496-71-5 Los juicios y las afirmaciones expresados en este documento son responsabilidad del autor, y el Instituto Electoral del Estado de México no los comparte necesariamente. Impreso en México. Publicación de distribución gratuita. Recepción de colaboraciones en [email protected] y [email protected] INSTITUTO ELECTORAL DEL ESTADO -

The Resilience of Mexico's

Mexico’s PRI: The Resilience of an Authoritarian Successor Party and Its Consequences for Democracy Gustavo A. Flores-Macías Forthcoming in James Loxton and Scott Mainwaring (eds.) Life after Dictatorship: Authoritarian Successor Parties Worldwide, New York: Cambridge University Press. Between 1929 and 2000, Mexico was an authoritarian regime. During this time, elections were held regularly, but because of fraud, coercion, and the massive abuse of state resources, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won virtually every election. By 2000, however, the regime came to an end when the PRI lost the presidency. Mexico became a democracy, and the PRI made the transition from authoritarian ruling party to authoritarian successor party. Yet the PRI did not disappear. It continued to be the largest party in Congress and in the states, and it was voted back into the presidency in 2012. This electoral performance has made the PRI one of the world’s most resilient authoritarian successor parties. What explains its resilience? I argue that three main factors explain the PRI’s resilience in the aftermath of the transition: 1) the PRI’s control over government resources at the subnational level, 2) the post-2000 democratic governments’ failure to dismantle key institutions inherited from the authoritarian regime, and 3) voters’ dissatisfaction with the mediocre performance of the PRI’s competitors. I also suggest that the PRI's resilience has been harmful in various ways, including by propping up pockets of subnational authoritarianism, perpetuating corrupt practices, and undermining freedom of the press and human rights. 1 Between 1929 and 2000, Mexico was an authoritarian regime.1 During this time, elections were held regularly, but because of fraud, coercion, and the massive abuse of state resources, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won virtually every election. -

Freedom in the World Annual Report, 2019, Mexico

Mexico | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/mexico A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 9 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 The president is elected to a six-year term and cannot be reelected. López Obrador of the left-leaning MORENA party won the July poll with a commanding 53 percent of the vote. His closest rival, Ricardo Anaya—the candidate of the National Action Party (PAN) as well as of the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) and Citizens’ Movement (MC)—took 22 percent. The large margin of victory prevented a recurrence of the controversy that accompanied the 2006 elections, when López Obrador had prompted a political crisis by refusing to accept the narrow election victory of conservative Felipe Calderón. The results of the 2018 poll also represented a stark repudiation of the outgoing administration of President Peña Nieto and the PRI; the party’s candidate, José Antonio Meade, took just 16 percent of the vote. The election campaign was marked by violence and threats against candidates for state and local offices. Accusations of illicit campaign activities remained frequent at the state level, including during the 2018 gubernatorial election in Puebla, where the victory of PAN candidate Martha Érika Alonso—the wife of incumbent governor Rafael Moreno—was only confirmed in December, following a protracted process of recounts and appeals related to accusations of ballot manipulation. (Both Alonso and Moreno died in a helicopter crash later that month.) A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 Senators are elected for six-year terms through a mix of direct voting and proportional representation, with at least two parties represented in each state’s delegation. -

Mexico's 2018 Election

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV History Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Liberal Arts 2018 Mexico's 2018 election Irving W. Levinson The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/hist_fac Part of the Election Law Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Levinson, Irving W., "Mexico's 2018 election" (2018). History Faculty Publications and Presentations. 40. https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/hist_fac/40 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MEXICO’S 2018 ELECTIONS OPENING NOTES On July 1, 2018, Mexico will hold elections for the presidency, for all seats in the federal Chamber of Deputies, and for one third of the seats in the federal Senate. Currently, nine political parties hold seats in one or both of the two houses of the federal legislature. Their names and the initials used in the following comments are: INITIALS PARTY NAME IN SPANISH PARTY NAME IN ENGLISH MORENA Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional Movement of National Regeneration MV Movimiento Ciudadano Citizen Movement NA Nueva Alianza New Alliance PAN Partido Acción Nacional National Action Party PES Partido Encuentro Social Social Encounter Party PRD Partido de la Revolución Democrática Party of the Democratic Revolution PRI Partido de la Revolución Institucional Party of the Institutional Revolution PVEM Partido Ecología Verde de Mexico Green Ecology Party of Mexico PT Partido Trabajo Party of Work THE CURRENT SITUATION Given the large number of political parties in Mexico, these nine parties formed alliances and in each case united behind a single presidential candidate. -

Anexo Uno Convenio De Coalición Electoral Parcial Que Celebran El Partido Político Nacional Morena, En Lo Sucesivo

ANEXO UNO CONVENIO DE COALICIÓN ELECTORAL PARCIAL QUE CELEBRAN EL PARTIDO POLÍTICO NACIONAL MORENA, EN LO SUCESIVO “MORENA”, REPRESENTADO POR EL C. MARIO MARTÍN DELGADO CARRILLO, PRESIDENTE DEL COMITÉ EJECUTIVO NACIONAL Y MINERVA CITLALLI HERNÁNDEZ MORA SECRETARIA GENERAL DEL COMITÉ EJECUTIVO NACIONAL, ASÍ COMO EL PARTIDO DEL TRABAJO, EN LO SUCESIVO “PT”, REPRESENTADO POR LOS CC. SILVANO GARAY ULLOA Y JOSÉ ALBERTO BENAVIDES CASTAÑEDA, COMISIONADOS POLÍTICOS NACIONALES DEL “PT” Y EL PARTIDO VERDE ECOLOGISTA DE MÉXICO, EN LO SUCESIVO “PVEM”, REPRESENTADO POR LA C. KAREN CASTREJÓN TRUJILLO, EN SU CALIDAD DE VOCERA DEL COMITÉ EJECUTIVO NACIONAL, CON EL OBJETO DE POSTULAR FÓRMULAS DE CANDIDATAS Y CANDIDATOS A DIPUTADAS Y DIPUTADOS POR EL PRINCIPIO DE MAYORÍA RELATIVA EN (151) CIENTO CINCUENTA Y UN, DE LOS TRESCIENTOS DISTRITOS ELECTORALES UNINOMINALES, EN QUE SE CONFORMAN E INTEGRAN EL PAÍS, CARGOS DE ELECCIÓN POPULAR A ELEGIRSE EN LA JORNADA COMICIAL FEDERAL ORDINARIA QUE TENDRÁ VERIFICATIVO EL 6 DE JUNIO DEL AÑO 2021, POR LOS QUE SE SOMETEN SU VOLUNTAD A LOS SIGUIENTES CAPÍTULADOS DE CONSIDERANDOS, ANTECEDENTES Y CLÁUSULAS. CAPÍTULO PRIMERO DE LOS CONSIDERANDOS. 1. Que el artículo 41 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos señala que el pueblo ejerce su soberanía por medio de los Poderes de la Unión y que la renovación de los poderes Legislativo y Ejecutivo se realizará mediante elecciones libres, auténticas y periódicas, señalando como una de las bases para ello el que los 1 ANEXO UNO partidos políticos sean entidades de interés público, así como que la ley determinará las formas específicas de su intervención en el Proceso Electoral y los derechos, obligaciones y prerrogativas que les corresponden. -

Continuity Or Rupture? Mexico's Energy Reform in Light of Electoral Expectations

CONTINUITY OR RUPTURE? MEXICO’S ENERGY REFORM IN LIGHT OF ELECTORAL EXPECTATIONS Miriam Grunstein, Ph.D. Nonresident Scholar, Mexico Center June 2018 © 2018 by the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Miriam Grunstein, Ph.D. “Continuity or Rupture? Mexico’s Energy Reform in Light of Electoral Expectations” Mexico’s Energy Reform in Light of Electoral Expectations Mexico’s future hinges on the outcome of the upcoming July 2018 presidential election. With just a few feet remaining from the finish line of the presidential race, the oldest horse, both in terms of age and political track record, is still a few steps ahead of the youngest, which follows in second place. A few days after the first presidential debate, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the “left-wing” candidate representing the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA, according to its acronym in Spanish), was still in the lead over Ricardo Anaya, the “right-wing,” National Action Party (PAN, according to its acronym in Spanish) candidate. The candidate from the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI, according to its acronym in Spanish)—José Antonio Meade—plods along at a slow pace, seeming to have not heard the gunshot that started the electoral race. -

MORENA and Mexico's Fourth Historical Transformation

ARTICLE MORENA and Mexico’s Fourth Historical Transformation by Gerardo Otero | Simon Fraser University | [email protected] On July 1, 2018, Mexico elected a left-of-center root causes that make the ruling class turn to president for the first time since Lázaro Cárdenas repression, said Abel Barrera Hernández, of the was elected in 1934. Andrés Manuel López Obrador Tlachinollán Center for Human Rights in the (AMLO) and his National Regeneration Movement highlands of Guerrero State. He therefore contested (MORENA) won the elections by a landslide, with the proposition that “the struggle for human rights 53.2 percent of the vote and 64.3 percent citizen is the axis of all struggle” because their violation is participation, winning a majority in both chambers merely a symptom. Yet, concrete responses and of Congress. The mandate is therefore quite strong. solutions are needed. The new government must Significantly, both Congress and the cabinet have respect and promote human rights, said Father gender parity, a first for any Latin American country. Miguel Concha, acknowledged as the dean of the Given the importance of these elections, Diálogos human rights struggle. He posited the indivisibility por la Democracia at the National Autonomous of three aspects of human rights. First, transitional University of Mexico (UNAM) organized a three- justice, which should be accessible to all in order day conference in November 2018 to analyze to avoid revictimization. Spaces from the bottom the challenges for the new government, which up should become available. Second, we need a promised a “fourth transformation” for Mexico. paradigm shift in security and to stay away from The first historical transformation was Mexico’s militarization. -

Influence Groups in the New Government of López Obrador

Influence Groups in the New Government of López Obrador México 11 2018 his year, over 40 countries held elections extraordinary negotiating efforts by Andrés Manuel to choose their heads of state. Several and sympathetic groups to facilitate the process of new developments have affected the perception political leaders coming to power. They paved the way and realities of democracies across the globe. for one of the most effective transitions seen since the TMexico’s recent elections (July 1st) marked a historical advent of democratic elections in the country. milestone, with around 56 million people (of a potential turnout of 89 million) casting their votes among an When launching the main points of this government’s unprecedented list of candidates that resulted in agenda, careful handling of the different management the victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as the styles of those in power can mean the difference country’s elect president. between success or failure. Formulating a long-term project as a party objective may depend on it. In this With the greatest voter turnout in Mexico’s history, and sense, it is worth noting that MORENA accepted a amid a context of clear rejection of preceding models of broad slate of different individuals as party members government, over 30 million voters elected a pure left- once its victory appeared to be imminent, causing wing leader to govern the second largest economy in internal divisions and polarization. Latin America for the first time in decades. Although the party’s charter2 and national legislation Collective discontent, blatant corruption throughout prohibit undercurrents or subgroups, this does not public administration, inequality indices, and a rising prevent the natural formation of influence groups that wave of violence and delinquency in the country set the directly or indirectly have a bearing on the decision- stage perfectly for the crushing victory of MORENA1 making processes of the country’s leader. -

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Mexico | Freedom House Page 1 of 23 MexicoFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 62 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 27 Civil Liberties 35 63 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/mexico/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Mexico | Freedom House Page 2 of 23 Mexico has been an electoral democracy since 2000, and alternation in power between parties is routine at both the federal and state levels. However, the country suffers from severe rule of law deficits that limit full citizen enjoyment of political rights and civil liberties. Violence perpetrated by organized criminals, corruption among government officials, human rights abuses by both state and nonstate actors, and rampant impunity are among the most visible of Mexico’s many governance challenges. Key Developments in 2019 • President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who took office in 2018, maintained high approval ratings through much of the year, and his party consolidated its grasp on power in June’s gubernatorial and local elections. López Obrador’s polling position began to wane late in the year, as Mexico’s dire security situation affected voters’ views on his performance. • In March, the government created a new gendarmerie, the National Guard, which officially began operating in June after drawing from Army and Navy police forces. Rights advocates criticized the agency, warning that its creation deepened the militarization of public security. • The number of deaths attributed to organized crime remained at historic highs in 2019, though the rate of acceleration slowed. Massacres of police officers, alleged criminals, and civilians were well-publicized as the year progressed. -

Redalyc.MORENA En La Reconfiguración Del Sistema De

Estudios Políticos ISSN: 0185-1616 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Espinoza Toledo, Ricardo; Navarrete Vela, Juan Pablo MORENA en la reconfiguración del sistema de partidos en México Estudios Políticos, vol. 9, núm. 37, enero-abril, 2016, pp. 81-109 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=426443710004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MOREna en la reconfiguración del sistema de partidos en México Ricardo Espinoza Toledo* Juan Pablo Navarrete Vela** Resumen En el presente texto se observa que el sistema de partidos en México se ha caracterizado por el establecimiento de tres ofertas políticas predominantes: PRI, Pan y PRD, correspondiente al pluralismo moderado. Sin embargo, este predominio tripartidista ha limitado el crecimiento de los partidos pequeños y la emergencia de una cuarta fuerza política competitiva. El pluralismo moderado no ha alentado el desarrollo electoral de los nuevos partidos, algo que también se refleja en la integración del Congreso. La emergencia deM OREna, partido político, vino a mo- dificar esa lógica, por su capacidad de convertirse en un partido competitivo, a la altura de los otros tres, bajo el liderazgo de Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Palabras clave: Pluralismo moderado, liderazgo carismático, partidos políticos, Izquierda, Sistema político mexicano. Abstract In the present ar tic le we obser ve that the system of par ties in M exic o has meant the establishment of three predominant political offerings: PRI, Pan and PRD, characteristic of moderate pluralism.