How an Induction Motor Works by Equations (And Physics)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct Torque Control of Induction Motors

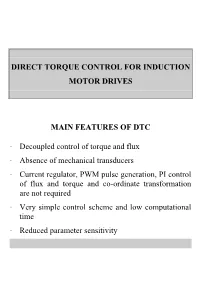

DIRECT TORQUE CONTROL FOR INDUCTION MOTOR DRIVES MAIN FEATURES OF DTC · Decoupled control of torque and flux · Absence of mechanical transducers · Current regulator, PWM pulse generation, PI control of flux and torque and co-ordinate transformation are not required · Very simple control scheme and low computational time · Reduced parameter sensitivity BLOCK DIAGRAM OF DTC SCHEME + _ s* s j s + Djs _ Voltage Vector s * T + j s DT Selection _ T S S S s Stator a b c Torque j s s E Flux vs 2 Estimator Estimator 3 s is 2 i b i a 3 Induction Motor In principle the DTC method selects one of the six nonzero and two zero voltage vectors of the inverter on the basis of the instantaneous errors in torque and stator flux magnitude. MAIN TOPICS Þ Space vector representation Þ Fundamental concept of DTC Þ Rotor flux reference Þ Voltage vector selection criteria Þ Amplitude of flux and torque hysteresis band Þ Direct self control (DSC) Þ SVM applied to DTC Þ Flux estimation at low speed Þ Sensitivity to parameter variations and current sensor offsets Þ Conclusions INVERTER OUTPUT VOLTAGE VECTORS I Sw1 Sw3 Sw5 E a b c Sw2 Sw4 Sw6 Voltage-source inverter (VSI) For each possible switching configuration, the output voltages can be represented in terms of space vectors, according to the following equation æ 2p 4p ö s 2 j j v = ç v + v e 3 + v e 3 ÷ s ç a b c ÷ 3 è ø where va, vb and vc are phase voltages. -

The Fundamentals of Ac Electric Induction Motor Design and Application

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF AC ELECTRIC INDUCTION MOTOR DESIGN AND APPLICATION by Edward J. Thornton Electrical Consultant E. I. du Pont de Nemours Houston, Texas and J. Kirk Armintor Senior Account Sales Engineer Rockwell Automation The Woodlands, Texas Edward J. (Ed) Thornton is an Electrical Electrical Mechanical Consultant in the Electrical Technology Coupling System Field System Consulting Group in Engineering at DuPont, in Houston, Texas. His specialty is the design, operation, and maintenance of electric power distribution systems and large motor installations. He has 20 years E , I T , w of consulting experience with DuPont. Mr. Thornton received his B.S. degree Figure 1. Block Representation of Energy Conversion for Motors. (Electrical Engineering, 1978) from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. The coupling magnetic field is key to the operation of electrical He is a registered Professional Engineer in the State of Texas. apparatus such as induction motors. The fundamental laws associated with the relationship between electricity and magnetism were derived from experiments conducted by several key scientists J. Kirk Armintor is a Senior Account in the 1800s. Sales Engineer in the Rockwell Automation Houston District Office, in The Woodlands, Basic Design and Theory of Operation Texas. He has 32 years’ experience with The alternating current (AC) induction motor is one of the most motor applications in the petroleum, rugged and most widely used machines in industry. There are two chemical, paper, and pipeline industries. major components of an AC induction motor. The stationary or He has authored technical papers on motor static component is the stator. The rotating component is the rotor. -

Abstract Controlling Ac Motor Using Arduino

ABSTRACT CONTROLLING AC MOTOR USING ARDUINO MICROCONTROLLER Nithesh Reddy Nannuri, M.S. Department of Electrical Engineering Northern Illinois University, 2014 Donald S Zinger, Director Space vector modulation (SVM) is a technique used for generating alternating current waveforms to control pulse width modulation signals (PWM). It provides better results of PWM signals compared to other techniques. CORDIC algorithm calculates hyperbolic and trigonometric functions of sine, cosine, magnitude and phase using bit shift, addition and multiplication operations. This thesis implements SVM with Arduino microcontroller using CORDIC algorithm. This algorithm is used to calculate the PWM timing signals which are used to control the motor. Comparison of the time taken to calculate sinusoidal signal using Arduino and CORDIC algorithm was also done. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2014 CONTROLLING AC MOTOR USING ARDUINO MICROCONTROLLER BY NITHESH REDDY NANNURI ©2014 Nithesh Reddy Nannuri A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING Thesis Director: Dr. Donald S Zinger ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Donald S. Zinger for his continuous support and guidance in this thesis work as well as throughout my graduate study. I would like to thank Dr. Martin Kocanda and Dr. Peng-Yung Woo for serving as members of my thesis committee. I would like to thank my family for their unconditional love, continuous support, enduring patience and inspiring words. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and everyone who has directly or indirectly helped me for their cooperation in completing the thesis. -

Electric Motors

SPECIFICATION GUIDE ELECTRIC MOTORS Motors | Automation | Energy | Transmission & Distribution | Coatings www.weg.net Specification of Electric Motors WEG, which began in 1961 as a small factory of electric motors, has become a leading global supplier of electronic products for different segments. The search for excellence has resulted in the diversification of the business, adding to the electric motors products which provide from power generation to more efficient means of use. This diversification has been a solid foundation for the growth of the company which, for offering more complete solutions, currently serves its customers in a dedicated manner. Even after more than 50 years of history and continued growth, electric motors remain one of WEG’s main products. Aligned with the market, WEG develops its portfolio of products always thinking about the special features of each application. In order to provide the basis for the success of WEG Motors, this simple and objective guide was created to help those who buy, sell and work with such equipment. It brings important information for the operation of various types of motors. Enjoy your reading. Specification of Electric Motors 3 www.weg.net Table of Contents 1. Fundamental Concepts ......................................6 4. Acceleration Characteristics ..........................25 1.1 Electric Motors ...................................................6 4.1 Torque ..............................................................25 1.2 Basic Concepts ..................................................7 -

Improvement of Electromagnetic Railgun Barrel Performance and Lifetime By

IMPROVEMENT OF ELECTROMAGNETIC RAILGUN BARREL PERFORMANCE AND LIFETIME BY METHOD OF INTERFACES AND AUGMENTED PROJECTILES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering by Aleksey Pavlov June 2013 c 2013 Aleksey Pavlov ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Improvement of Electromagnetic Rail- gun Barrel Performance and Lifetime by Method of Interfaces and Augmented Pro- jectiles AUTHOR: Aleksey Pavlov DATE SUBMITTED: June 2013 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Kira Abercromby, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Aerospace Engineering COMMITTEE MEMBER: Eric Mehiel, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Aerospace Engineering COMMITTEE MEMBER: Vladimir Prodanov, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Electrical Engineering COMMITTEE MEMBER: Thomas Guttierez, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Physics iii Abstract Improvement of Electromagnetic Railgun Barrel Performance and Lifetime by Method of Interfaces and Augmented Projectiles Aleksey Pavlov Several methods of increasing railgun barrel performance and lifetime are investigated. These include two different barrel-projectile interface coatings: a solid graphite coating and a liquid eutectic indium-gallium alloy coating. These coatings are characterized and their usability in a railgun application is evaluated. A new type of projectile, in which the electrical conductivity varies as a function of position in order to condition current flow, is proposed and simulated with FEA software. The graphite coating was found to measurably reduce the forces of friction inside the bore but was so thin that it did not improve contact. The added contact resistance of the graphite was measured and gauged to not be problematic on larger scale railguns. The liquid metal was found to greatly improve contact and not introduce extra resistance but its hazardous nature and tremendous cost detracted from its usability. -

Permanent Magnet Servomotor and Induction Motor Considerations

Permanent Magnet Servomotor and Induction Motor Considerations Kollmorgen B-104 PM Brushless Servomotor at 0.4 HP Kollmorgen M-828 PM Brushless Rotor Kollmorgen B-802 PM Brushless Servomotor at 15 HP Kollmorgen B-808 PM Brushless Rotor Permanent Magnet Servomotor and Induction Motor Considerations 1 Lee Stephens, Senior Motion Control Engineer Permanent Magnet Servomotor and Induction Motor Considerations Motion long considered a mainstay of induction motors, encroachment in the area of 50 HP and greater have been seen recently for some applications by permanent magnet (PM) servomotors. These applications usually have dynamic considerations that require position-time closed loop and high accelerations. When accelerating large loads, permanent magnet servomotors can work with very high load to inertia ratios and still maintain performance requirements. Having a lower inertia typically will allow for less permanent magnet motor can result in a greater torque energy wasted within the motor. Torque (τ), is the density than an equivalent induction system. If size product of inertia (j) and rotary acceleration (α). If you matters, then perhaps a system should use one require inertia matching, ½ of your energy is wasted technology over another. Speaking of size, the inertia accelerating the motor alone. If the inertia ratio from ratio can be an important figure of merit should motor to load is large, then control schemes must be dynamic needs arise. If you are going to have high dynamic enough to prevent the larger load from driving accelerations and decelerations, the size of the rotor the motor as opposed to the motor controlling the load. will significantly increase the inertia and decrease the Tradeoffs and knowing what can be negotiated. -

Hyperloop Accelerator Design Review

Hyperloop Accelerator Design Review TA: Benjamin Cahill ECE 445 February 25, 2015 Mohammad Jaber Michael Eraci Shivam Sharma Group #24 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Statement of Purpose................................................................................. 3 1.2 Objectives...................................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Benefits ........................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Features .......................................................................................... 3 2.0 Design......................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Block Diagram .............................................................................................. 4 2.2 Block Descriptions...................................................................................... 5 3.0 Schematics and Simulation .................................................................................. 6 3.1 Circuit Diagram ............................................................................................ 6 3.2 Control Flow Diagram ................................................................................ 7 3.3 Simulations ................................................................................................... 7 4.0 Requirements -

ALTERNATORS ➣ Armature Windings ➣ Wye and Delta Connections ➣ Distribution Or Breadth Factor Or Winding Factor Or Spread Factor ➣ Equation of Induced E.M.F

CHAPTER37 Learning Objectives ➣ Basic Principle ➣ Stationary Armature ➣ Rotor ALTERNATORS ➣ Armature Windings ➣ Wye and Delta Connections ➣ Distribution or Breadth Factor or Winding Factor or Spread Factor ➣ Equation of Induced E.M.F. ➣ Factors Affecting Alternator Size ➣ Alternator on Load ➣ Synchronous Reactance ➣ Vector Diagrams of Loaded Alternator ➣ Voltage Regulation ➣ Rothert's M.M.F. or Ampere-turn Method ➣ Zero Power Factor Method or Potier Method ➣ Operation of Salient Pole Synchronous Machine ➣ Power Developed by a Synchonous Generator ➣ Parallel Operation of Alternators ➣ Synchronizing of Alternators ➣ Alternators Connected to Infinite Bus-bars ➣ Synchronizing Torque Tsy ➣ Alternative Expression for Ç Alternator Synchronizing Power ➣ Effect of Unequal Voltages ➣ Distribution of Load ➣ Maximum Power Output ➣ Questions and Answers on Alternators 1402 Electrical Technology 37.1. Basic Principle A.C. generators or alternators (as they are DC generator usually called) operate on the same fundamental principles of electromagnetic induction as d.c. generators. They also consist of an armature winding and a magnetic field. But there is one important difference between the two. Whereas in d.c. generators, the armature rotates and the field system is stationary, the arrangement Single split ring commutator in alternators is just the reverse of it. In their case, standard construction consists of armature winding mounted on a stationary element called stator and field windings on a rotating element called rotor. The details of construction are shown in Fig. 37.1. Fig. 37.1 The stator consists of a cast-iron frame, which supports the armature core, having slots on its inner periphery for housing the armature conductors. The rotor is like a flywheel having alternate N and S poles fixed to its outer rim. -

13 Electric Motors

13 ELECTRIC MOTORS Modern underwater vehicles and surface vessels are making increased use of electrical ac tuators, for all range of tasks including weaponry, control surfaces, and main propulsion. This section gives a very brief introduction to the most prevalent electrical actuators: The DC motor, the AC induction motor, and the AC synchronous motor. For the latter two technologies, we consider the case of three-phase power, which is generally preferred over single-phase because of much higher power density; three-phase motors also have simpler starting conditions. AC motors are generally simpler in construction and more robust than DC motors, but at the cost of increased control complexity. This section provides working parametric models of these three motor types. As with gas turbines and diesel engines, the dynamic response of the actuator is quite fast compared to that of the system being controlled, say a submarine or surface vessel. Thus, we concentrate on portraying the quasi-static properties of the actuator – in particular, the torque/speed characteristics as a function of the control settings and electrical power applied. The discussion below on these various motors is generally invertible (at least for DC and AC synchronous devices) to cover both motors (electrical power in, mechanical power out) and generators (mechanical power in, electrical power out). We will only cover motors in this section, however; a thorough treatment of generators can be found in the references listed. The book by Bradley (19??) has been drawn on heavily in the following. 13.1 Basic Relations 13.1.1 Concepts First we need the notion of a magnetic flux, analagous to an electrical current, denoted �; a common unit is the Weber or Volt-second. -

Dynamics Induced in Microparticles by Electromagnetic Fields

DYNAMICS INDUCED IN MICROPARTICLES BY ELECTROMAGNETIC FIELDS A conceptual introduction to nanoelectromechanical systems Patricio Robles Escuela de Ingeniería Eléctrica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile Roberto Rojas Departamento de Física, Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Valparaíso, Chile Italo Chiarella Escuela de Ingeniería Eléctrica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile 1 PREFACE This is a review addressed to undergraduate students of electrical engineering and physics careers, and our aim is to present a pedagogical integration of some knowledge acquired in electromagnetism and electromechanical energy conversion courses, and to show how they can be used in actual technology applications, in particular for microscopic and nanoscopic systems. In general, the contents of electromagnetic courses looks rather abstract to students at an intermediate level of the electrical engineering career and its applications are hard to be appreciated by them. The course of electromechanical energy conversion provides to the students a good link with processes of electrical engineering but in our opinion it is necessary a book containing a better integration and correlation of topics learned in these courses, such as energy and momentum transfer between electromagnetic fields and movile devices, at a macroscopic and at a microscopic level. At a macroscopic scale, in general a good integration results in these courses for understanding how by means of variation in the energy stored in the magnetic field and interaction between rotating magnetic fields it is possible to produce mechanical or electric power for the operation of motors or generators, respectively. In general the programs of these courses give less emphasis on similar processes that are possible with the energy stored in the electric field as is the case, for example, of capacitors with movile plates or the interaction between electric polarized objects with rotating electric fields. -

Chapter 3 Model of a Three-Phase Induction Motor

CHAPTER 3 MODEL OF A THREE-PHASE INDUCTION MOTOR 3.1 Introduction The induction machine is used in wide variety of applications as a means of converting electric power to mechanical power. Pump steel mill, hoist drives, household applications are few applications of induction machines. Induction motors are most commonly used as they offer better performance than other ac motors. In this chapter, the development of the model of a three-phase induction motor is examined starting with how the induction motor operates. The derivation of the dynamic equations, describing the motor is explained. The transformation theory, which simplifies the analysis of the induction motor, is discussed. The steady state equations for the induction motor are obtained. The basic principles of the operation of a three phase inverter is explained, following which the operation of a three phase inverter feeding a induction machine is explained with some simulation results. 3.2. Basic Principle Of Operation Of Three-Phase Induction Machine The operating principle of the induction motor can be briefly explained as, when balanced three phase voltages displaced in time from each other by angular intervals of 120o is applied to a stator having three phase windings displaced in space by 120o electrical, a rotating magnetic field is produced. This rotating magnetic field 45 has a uniform strength and rotates at the supply frequency, the rotor that was assumed to be standstill until then, has electromagnetic forces induced in it. As the rotor windings are short circuited, currents start circulating in them, producing a reaction. As known from Lenz’s law, the reaction is to counter the source of the rotor currents. -

Design and Fabrication of Moto Autor

A. John Joseph Clinton Int. Journal of Engineering Research and Applications www.ijera.com ISSN : 2248-9622, Vol. 5, Issue 1( Part 4), January 2015, pp.07-16 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Design and Fabrication of Moto Autor A. John Joseph Clinton*, P. Rajkumar** *(Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chandy College of Engineering, Affliated to Anna University- Chennai, Tuticorin-05) ** (Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chandy College of Engineering,Affliated to Anna University- Chennai, Tuticorin-05) ABSTRACT This project is based on the need for the unconventional motor. This work will be another addition in the unconventional revolution. Our project is mainly composed of design and fabrication of the ―MOTO AUTOR‖ which is a replacement of conventional motors in many applications of it. This motoautor can run on its own without any traditional input for fuelling it except for the initiation where permanent magnets has to be installed at first. It is a perpetual motion system that can energize itself by taking up the free energy present in the nature itself. This project enables to motorize systems with very minimal expenditure of energy. Keywords–Perpetual motion, Free energy conversion, Unconventional motor, Magnetic principles, Self- energizing I. INTRODUCTION Perhaps the first electric motors were In normal motoring mode, most electric motors simple electrostatic devices created by the Scottish operate through the interaction between an electric monk Andrew Gordon in the 1740s. The theoretical motor's magnetic field and winding currents to principle behind production of mechanical force by generate force within the motor. In certain the interactions of an electric current and a magnetic applications, such as in the transportation industry field, Ampère's force law, was discovered later with traction motors, electric motors can operate in by André-Marie Ampère in 1820.