Gender and Land Tenure Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No

AO AO Name Address Block District Mobile Email Code Number 97634 Chandra Rekha Shivpuri Shiv Mandir Road Ward No 09 Araria Araria 9661056042 [email protected] Development Foundation Araria Araria 97500 Divya Dristi Bharat Divya Dristi Bharat Chitragupt Araria Araria 9304004533 [email protected] Nagar,Ward No-21,Near Subhash Stadium,Araria 854311 Bihar Araria 100340 Maxwell Computer Centre Hanumant Nagar, Ward No 15, Ashram Araria Araria 9934606071 [email protected] Road Araria 98667 National Harmony Work & Hanumant Nagar, Ward No.-15, Po+Ps- Araria Araria 9973299101 [email protected] Welfare Development Araria, Bihar Araria Organisation Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No. 16,Near Araria Araria 7644088124 [email protected] Durga Mandir Araria 97613 Sarthak Foundation C/O - Taranand Mishra , Shivpuri Ward Araria Araria 8757872102 [email protected] No. 09 P.O + P.S - Araria Araria 98590 Vivekanand Institute Of 1st Floor Milan Market Infront Of Canara Araria Araria 9955312121 [email protected] Information Technology Bank Near Adb Chowk Bus Stand Road Araria Araria 100610 Ambedkar Seva Sansthan, Joyprakashnagar Wardno-7 Shivpuri Araria Araria 8863024705 [email protected] C/O-Krishnamaya Institute Joyprakash Nagar Ward No -7 Araria Of Higher Education 99468 Prerna Society Of Khajuri Bazar Araria Bharga Araria 7835050423 [email protected] Technical Education And ma Research 100101 Youth Forum Forbesganj Bharga Araria 7764868759 [email protected] -

District Health Action Plan Siwan 2012 – 13

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN SIWAN 2012 – 13 Name of the district : Siwanfloku Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Foreword National Rural health Mission was launched in India in the year 2005 with the purpose of improving the health of children and mothers and reaching out to meet the health needs of the people in the hard to reach areas of the nation. National Rural Health Mission aims at strengthening the rural health infrastructures and to improve the delivery of health services. NRHM recognizes that until better health facilities reaches the last person of the society in the rural India, the social and economic development of the nation is not possible. The District Health Action Plan of Siwan district has been prepared keeping this vision in mind. The DHAP aims at improving the existing physical infrastructures, enabling access to better health services through hospitals equipped with modern medical facilities, and to deliver the health service with the help of dedicated and trained manpower. It focuses on the health care needs and requirements of rural people especially vulnerable groups such as women and children. The DHAP has been prepared keeping in mind the resources available in the district and challenges faced at the grass root level. The plan strives to bring about a synergy among the various components of the rural health sector. In the process the missing links in this comprehensive chain have been identified and the Plan will aid in addressing these concerns. The plan has attempts to bring about a convergence of various existing health programmes and also has tried to anticipate the health needs of the people in the forthcoming years. -

Clbr291116.Pdf

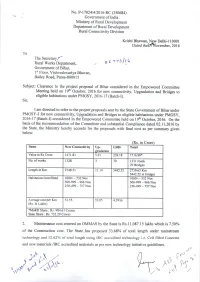

Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana Road List for attachment with Sanction Letter - District Wise Abstract State : Bihar Sanction Year : 2016-2017 Batch : 1 Collaboration : Regular PMGSY Sr.No. District No of Road Length MoRD Cost State Cost (Rs Total Cost Maint. Cost Habs (1000+, 500+, 250+, <250, Total) Works (Kms) / Bridge (Rs Lacs) Lacs) (Rs Lacs) (Rs Lacs) Length (Mtrs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Road Proposals 1 Araria 14 53.847 2,028.42 1,352.29 3,380.71 359.41 (38 , 22 , 7 , 6 , 73) 2 Arwal 17 24.592 789.32 526.21 1,315.53 94.39 (2 , 8 , 9 , 0 , 19) 3 Aurangabad 98 247.119 7,472.00 4,981.32 12,453.32 769.17 (30 , 43 , 63 , 31 , 167) 4 Banka 51 154.415 4,878.39 3,252.27 8,130.66 901.54 (5 , 56 , 10 , 47 , 118) 5 Begusarai 6 7.749 202.83 135.22 338.05 22.97 (3 , 4 , 3 , 1 , 11) 6 Bhagalpur 9 30.252 974.39 649.59 1,623.98 190.73 (5 , 5 , 1 , 0 , 11) 7 Bhojpur 12 23.800 894.47 596.34 1,490.81 130.11 (5 , 9 , 1 , 0 , 15) 8 Buxar 5 9.990 395.39 263.61 659.00 58.31 (0 , 6 , 0 , 0 , 6) 9 Darbhanga 20 58.903 1,910.50 1,273.67 3,184.17 139.63 (30 , 23 , 22 , 24 , 99) 10 East Champaran 67 124.877 4,000.46 2,667.01 6,667.47 385.71 (32 , 50 , 22 , 32 , 136) 11 Gaya 200 311.574 8,617.98 5,745.35 14,363.33 1,149.84 (44 , 107 , 143 , 45 , 339) 12 Gopalganj 6 24.150 749.26 499.80 1,249.06 56.40 (0 , 7 , 0 , 0 , 7) 13 Jahanabad 15 19.397 556.53 371.02 927.55 73.72 (2 , 5 , 12 , 6 , 25) 14 Jamui 9 55.851 1,706.79 1,137.86 2,844.65 202.73 (0 , 1 , 14 , 58 , 73) 15 Kaimur (Bhabhua) 106 204.660 6,353.25 4,235.54 10,588.79 952.99 (7 , 45 , 93 , 41 , 186) 16 Katihar -

District Profile Siwan Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE SIWAN INTRODUCTION Siwan district is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. Situated in western Bihar, Siwan was originally a sub-division of Saran district. It was notified as a district on 11th December, 1972. The district of Gopalganj was carved out of Siwan district in 1973. Siwan district is bounded by Saran and Gopalganj districts of Bihar and Deoria and Balia districts of Uttar Pradesh. The rivers flowing through Siwan district are Ghaghara(Gogra or Saryu), Jharahi, Daha, Gandaki, Dhamati (Dhamahi), Siahi, Nikari and Sona. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Siwan derives its name from "Shiv Man", a Bandh Raja whose heirs ruled this area till the arrival of Babur. Siwan is also known as Aliganj Siwan after the name of Ali Bux, a feudal lords of the area. Maharajganj may have found its name from the seat of the Maharaja there. Historically, Siwan formed a part of Kosala kingdom and Banaras kingdom. The statue of Lord Vishnu excavated in village Bherbania from underneath a tree suggests that people were devotees of Lord Vishnu. The Muslims rule began in Siwan during the 13th century. Sikandar Lodi ruled in Siwan in the 15th century. Babur crossed Ghaghra river near Siswan on his return journey from Bihar. After the battle of Buxar in 1765, Siwan became a part of Bengal. Siwan played an important role in the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. A sizable number of Sepoys of East India Company drawn from this region- the stalwart and sturdy ‘Bhojpuris’, noted for their martial spirit and physical endurance, rebelled against the Company and joined Babu Kunwar Singh, the Zamindar of Jagdishpur, who lead the mutiny in Bhojpur. -

District Health Society Siwan 2010-2011

District Health Society Siwan District Health Action Plan 2010-2011 Developed & Designed By • Thakur Vishwa Mohan (DPM) • Md. Nausad(DAM) • Pankaj Kumar Singh (District Nodal M & E Officer) Dr. Vibhesh Pd. Singh Dr. Bhairaw Prasad Sri Bala Murugan D Aditional Chief Medical Chief Medical Officer IAS officer Cum District Magistrate Siwan Member Secretary, DHS, Cum Siwan Chairman, DHS, Siwan 1 Foreword National Rural Health Mission aims at strengthening the rural health infrastructures and to improve the delivery of health services. NRHM recognizes that until better health facilities reaches the last person of the society in the rural India, the social and economic development of the nation is not possible. The District Health Action Plan of Siwan district has been prepared keeping this vision of mind. The DHAP aims at improving the existing physical infrastructures, enabling access to better health services through hospitals equipped with modern medical facilities, and to deliver with the help of dedicated and trained manpower. It focuses on the health care needs and requirements of rural people especially vulnerable groups such as women and children. The DHAP has been prepared keeping in mind the resources available in the district and challenges faced at the grass root level. The plan strives to bring about a synergy among the various components of the rural health sector. In the process the missing links in this comprehensive chain have been identified and the Plan will aid in addressing these concerns. The plan has attempts to bring about a convergence of various existing health programmes and also has tried to anticipate the health needs of the people in the forthcoming years. -

District Health Society Siwan District Health Action Plan 2011-2012

District Health Society Siwan District Health Action Plan 2011-2012 Developed & Designed By Thakur Vishwa Mohan (DPM) Randheer Kumar (DAM) Pankaj Kumar Singh (District Nodal M & E Officer) Imamul Hoda (DPC) Dr. Vibhesh Pd. Singh Dr.Chandrashekhar Sri Lokesh Kumar Singh Additional Chief Medical Kumar IAS officer Chief Medical Officer District Magistrate Siwan Cum Cum Member Secretary, DHS, Chairman, DHS, Siwan Siwan 1 Create PDF files without this message by purchasingSIWAN novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Foreword National Rural Health Mission aims at strengthening the rural health infrastructures and to improve the delivery of health services. NRHM recognizes that until better health facilities reaches the last person of the society in the rural India, the social and economic development of the nation is not possible. The District Health Action Plan of Siwan district has been prepared keeping this vision in mind. The DHAP aims at improving the existing physical infrastructures, enabling access to better health services through hospitals equipped with modern medical facilities, and to deliver the health service with the help of dedicated and trained manpower. It focuses on the health care needs and requirements of rural people especially vulnerable groups such as women and children. The DHAP has been prepared keeping in mind the resources available in the district and challenges faced at the grass root level. The plan strives to bring about a synergy among the various components of the rural health sector. In the process the missing links in this comprehensive chain have been identified and the Plan will aid in addressing these concerns. The plan has attempts to bring about a convergence of various existing health programmes and also has tried to anticipate the health needs of the people in the forthcoming years. -

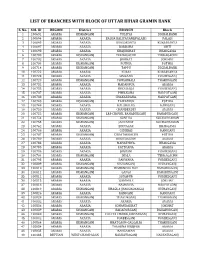

List of Branches with Block of Uttar Bihar Gramin Bank

LIST OF BRANCHES WITH BLOCK OF UTTAR BIHAR GRAMIN BANK S. No. SOL ID REGION District BRANCH Block 1 100691 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TULSIYA DIGHALBANK 2 100694 ARARIA ARARIA BALUA KALIYAGANJ(PALASI) PALASI 3 100695 ARARIA ARARIA KURSAKANTA KURSAKANTA 4 100697 ARARIA ARARIA BARDAHA SIKTI 5 100698 ARARIA ARARIA KHAJURIHAT BHARGAMA 6 100700 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TERHAGACHH TERRAGACHH 7 100702 ARARIA ARARIA JOKIHAT JOKIHAT 8 100704 ARARIA KISHANGANJ POTHIA POTHIA 9 100714 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TAPPU DIGHALBANK 10 100722 ARARIA ARARIA KUARI KURSAKANTA 11 100723 ARARIA ARARIA SIMRAHA FORBESGANJ 12 100729 ARARIA KISHANGANJ POWAKHALI THAKURGANJ 13 100732 ARARIA ARARIA MADANPUR ARARIA 14 100733 ARARIA ARARIA DHOLBAJJA FORBESGANJ 15 100737 ARARIA ARARIA PHULKAHA NARPATGANJ 16 100738 ARARIA ARARIA CHAKARDAHA. NARPATGANJ 17 100748 ARARIA KISHANGANJ TAIYABPUR POTHIA 18 100749 ARARIA ARARIA KALABALUA RANIGANJ 19 100750 ARARIA ARARIA CHANDERDEI ARARIA 20 100752 ARARIA KISHANGANJ LRP CHOWK, BAHADURGANJ BAHADURGANJ 21 100754 ARARIA KISHANGANJ SONTHA KOCHADHAMAN 22 100755 ARARIA KISHANGANJ JANTAHAT KOCHADHAMAN 23 100762 ARARIA ARARIA BIRNAGAR BHARGAMA 24 100766 ARARIA ARARIA GIDHBAS RANIGANJ 25 100767 ARARIA KISHANGANJ CHHATARGACHH POTHIA 26 100780 ARARIA ARARIA KUSIYARGAW ARARIA 27 100783 ARARIA ARARIA MAHATHWA. BHARGAMA 28 100785 ARARIA ARARIA PATEGANA. ARARIA 29 100786 ARARIA ARARIA JOGBANI FORBESGANJ 30 100794 ARARIA KISHANGANJ JHALA TERRAGACHH 31 100795 ARARIA ARARIA PARWAHA FORBESGANJ 32 100809 ARARIA KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ 33 100810 ARARIA KISHANGANJ -

COMMUNICATION PLAN.Xlsx

Block Development And Circle Officers Contact Details Sl. No. Name Designation Email Mobile No Landline No Fax No Address BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, SIWAN B.D.O. SIWAN SADAR [email protected] 9431818189 6154240216 1 SIWAN SADAR SADAR BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. SISWAN [email protected] 9431818543 6154275472 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, SISWAN 2 SISWAN BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, B.D.O. PACHRUKHI [email protected] 9431818180 6154281453 3 PACHRUKHI PACHRUKHI BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. NAUTAN [email protected] 9431818191 6157262672 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, NAUTAN 4 NAUTAN BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. MAIRWA [email protected] 9431818541 6157232980 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, MAIRWA 5 MAIRWA BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. ZIRADEI [email protected] 9431818185 6154286992 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, ZIRADEI 6 ZIRADEI BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. GUTHANI [email protected] 9431818183 6157252301 7 GUTHANI GUTHANI BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, B.D.O. AANDAR [email protected] 9431818182 6154284310 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, AANDER 8 AANDER BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, B.D.O. DARAUNDHA [email protected] 9431818544 6153271349 9 DARAUNDHA DARAUNDHA BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, B.D.O. BASANTPUR [email protected] 9431818190 6153242804 10 BASANTPUR BASANTPUR BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, B.D.O HUSSAINGANJ [email protected] 9431818186 6154278381 11 HUSSAINGANJ HUSSAINGANJ BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER, BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICE, B.D.O. -

Bihar Building New Avenues of Progress Bihar

BIHAR BUILDING NEW AVENUES OF PROGRESS BIHAR Uttar Pradesh Jharkhand West Bengal In the State of Bihar, a popular destination for spiritual tourists from all over the world, the length of National Highways has been doubled in the past four years. Till 2014, the length of National Highways was 4,447 km. In 2018, the length of National Highways has reached 8,898 km. The number of National Highways have been increased to 102 in 2018. Road development works worth Rs. 20,000 Cr are progressing rapidly. In the next few years, investments worth Rs. 60,000 Cr will be made towards transforming the road sector in Bihar, and creating new socio-economic opportunities for the people. “When a network of good roads is created, the economy of the country also picks up pace. Roads are veins and arteries of the nation, which help to transform the pace of development and ensure that prosperity reaches the farthest corners of our nation.” NARENDRA MODI Prime Minister “In the past four years, we have expanded the length of Indian National Highways network to 1,26,350 km. The highway sector in the country has seen a 20% growth between 2014 and 2018. Tourist destinations have come closer. Border, tribal and backward areas are being connected seamlessly. Multimodal integration through road, rail and port connectivity is creating socio economic growth and new opportunities for the people. In the coming years, we have planned projects with investments worth over Rs 6 lakh crore, to further expand the world’s second largest road network.” NITIN GADKARI Union Minister, -

AN ANALYSIS of SPATIAL ORGANISATION of SCHEDULED CASTES in NORTH-WESTERN BIHAR,INDIA Dr

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9, Issue 3, March - 2019, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A AN ANALYSIS OF SPATIAL ORGANISATION OF SCHEDULED CASTES IN NORTH-WESTERN BIHAR,INDIA Dr. Abdul Amim P.G.T., HIGH SCHOOL CUM INTER COLLEGE, SAMARDAH, SIWAN, BIHAR ABSTRACT The distribution or spatial pattern of scheduled caste population in an areal unit can be considered as an index of the growth and pattern of development. The nature of distribution of these backward and depressed classes is a result of historical and socio-economic factors. A sincere attempt has been taken to reveal the demographic structure and the features of scheduled caste population in Siwan, a district located in north- western part of Bihar. INTRODUCTION The scheduled caste population is linked in space and time as it is a geographical study. The space and time relationship is an important theme in the explanation of the characteristics of the scheduled caste population. This study depicts the features of dalits of India in general and Siwan district in the north-west Bihar in particular. These communities have made great achievements in their social, political and religious Spheres. Despite these achievements, most of the dalits of India as well as the district of siwan still live below poverty line. -

Sl. No. Districts Physical Target As Per ROP 2017- 18 (Physical Indicator Is No. of SNCU) District Total Allotment 2017- 18

Annexure-1 Annexure-1 ROP/FMR Budget code No.(as per ROP 2017- ROP/FMR Budget code No.(as per ROP 2017-18):Part- : 18):Part- : A.2.2.1 A.2.2.1.1 Child Health ROP/FMR Budget Head: SNCU ROP/FMR Budget Head: SNCU Data management (excluding HR) Physical Target as per ROP 2017- District Total Allotment 2017- Physical Target as per ROP 2017-18 District Total Allotment Sl. No. Districts 18 (Physical 18 (Physical indicator is no. of SNCU 2017-18 indicator is no. of (in Rs.) @11000/SNCU/ month) (in Rs.) SNCU) a b f (g+h) f (g+h) 35 Siwan 1 1000000 0 0 1 Andar 0 0 2 Barharia 0 0 3 Basantpur 0 0 4 Bhagwanpur 0 0 5 Darauli 0 0 6 Daraunda 0 0 7 Goriakothi 0 0 8 Guthani 0 0 9 Hassanpura 0 0 10 Hussainganj 0 0 11 Lakri Nabigunj 0 0 12 Mahrajgunj 0 0 13 Mairwa 0 0 14 Nautan 0 0 15 Pachrukhi 0 0 16 Raghunathpur 0 0 17 Sadar Block 0 0 18 Siswan 0 0 19 Ziradei 0 0 20 SDH Mahrajgunj 0 0 21 Sadar Hospital 1 1000000 Total 1 1000000 0 0 District Level Fund Retention 0 0 0 0 Grand Total 1 1000000 0 0 SPO SPM E.D Annexure-1 Annexure-1 ROP/FMR Budget code No.(as per ROP 2017-18):Part- : A.2.2.2 ROP/FMR Budget code No.(as per ROP 2017-18):Part- : A.2.2.3 Child Health ROP/FMR Budget Head: NBSU ROP/FMR Budget Head: NBCC Physical Target as Physical Target as per ROP 2017-18 District Total Allotment 2017- per ROP 2017-18 District Total Allotment 2017-18 Sl. -

Pscommunication23 Mar 2019

Polling Station Nearest Nearest Police Zonal Officer Sector Magistrate Any Other Suitable local BLO Yes/ Distri Ac No and W Name of Di Zo Sec Name Name Desi Name of Cont Cr PS Sl. No. Person's Mobil Mobile Zone Officer Mobil Officer Mobil Mobil Mobil Block Mobile ct Name No & Name ir Police st ne tor of of Name gnat office in rolin iti ha Name e No. No. Name Name e No. Name e No. e No. e No. Name No. el Station an No. No person person ion which g ca vi 1 16 - 109 - 001 - Utkramit madhya SURENDRA 751936 Noe HUSSAINGAN 4ce 94318224 DARAUNDA 109 SUNIL 943181 1 SONU 837705 AJAYrunner 850771 MANJITrunner 732484 KUMARI SEWIK CDPOpost CDPOOffic HASANPURA 8969462 Yesl Nong Siwan Daraundha vidhyalay Prasadipur, YADAV 3763 J 58 KUMAR 8363 KUMAR 7569 YADAV 4566 KUMAR 3816 UMA A 528 Sahuli Daya bhag 2 16 - 109 - 002 - Utkramit madhy ANIL KUMAR 800292 No HUSSAINGAN 5 94318224 DARAUNDA 109 SUNIL 943181 1 SONU 837705 AJAY 778190 MUKESH 950798 ANIRUDH TEACH BEO BEO HASANPURA 8969462 Yes No Siwan Daraundha vidhayalay prsadipur YADAV 8707 J 58 KUMAR 8363 KUMAR 7569 KUMAR 8607 YADAV 3104 RAM ER 528 sahuli Baya Bhag YADAV 3 16 - 109 - 003 - Utkramit Madhya RAMU SAH 865107 No HUSSAINGAN 5 94318224 DARAUNDA 109 SUNIL 943181 1 SONU 837705 LALAN SAH 865106 SUBHASH 829238 RAMBHA SEWIK CDPO CDPO HASANPURA 9507427 Yes No Siwan Daraundha vidhalya knya sahuli 0169 J 58 KUMAR 8363 KUMAR 7569 9513 SAH 6767 DEVI A 598 4 16 - 109 - 004 - Kanya Prathamik SUNIL PRASAD 919904 No HUSSAINGAN 5 94318224 DARAUNDA 109 SUNIL 943181 1 SONU 837705 MERAJUDI 970840 KHURSHID 765474