George L. Carter's Clinchfield Railroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

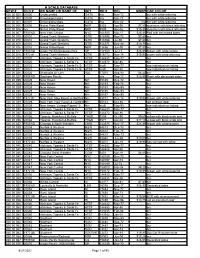

NSC 2020 Early March Auction Results

MFG MODEL SCALE ROADNAME ROAD # VARIATION # PRICE MEMBER MTL 20090 N SOUTHERN PACIFIC 97947 SINGLE CAR 1 MTL 20170 N BURLINGTON-CB&Q 62988 WZ @ BW 2 MTL 20240 N NEW YORK CENTRAL 174710 PACEMAKER 3 MTL 20240 N NEW YORK CENTRAL 174710 PACEMAKER 4 $11.00 6231 MTL 20630 N WEST INDIA FRUIT 101 5 $19.00 5631 MTL 20850 N SPOKANE, PORTLAND & SEATTLE 12218 6 MTL 20880 N LAKE SUPERIOR & ISHPEMING 2290 7 $14.00 1687 MTL 20880 N LAKE SUPERIOR & ISHPEMING 2290 7 $14.00 6258 MTL 20950 N CHICAGO GREAT WESTERN 90017 8 MTL 20970 N PACIFIC GREAT EASTERN 4022 9 $14.00 1687 MTL 20066 N PENNSYLVANIA 30902 "MERCHANDISE SERVICE" 10 MTL 20086 N MICROTRAINS LINE COMPANY 1991 1ST ANNIVERSARY 11 MTL 20126 N LEHIGH VALLEY 62545 12 $10.00 2115 MTL 20186 N GREAT NORTHERN 19617 CIRCUS CAR #7 -RED 13 MTL 20306/2 N BURLINGTON NORTHERN 189288 14 MTL 20346 N BALTIMORE & OHIO 470687 "TIMESAVER" 15 MTL 20346-2 N BALTIMORE & OHIO 470751 16 MTL 20486 N MONON 861 "THE HOOSIER LINE" 17 $18.00 6258 MTL 21020 N STATE OF MAINE 2231 40' STANDARD BXCR, PLUG DOOR 18 MTL 21040 N GREAT NORTHERN 7136 40' STANDARD BXCR, PLUG DOOR 19 $19.00 2115 MTL 21212 N BURLINGTON NORTHERN 4-PACK "FALLEN FLAGS #03 20 MTL 21230 N BRITISH COLUMBIA RAILWAY 8002 21 MTL 22030 N UNION PACIFIC 110013 22 MTL 22180 N MILWAUKEE 29960 23 MTL 23230 N UNION PACIFIC 9149 "CHALLENGER" 24 $24.00 4489 MTL 23240 N ASHLEY, DREW & NORTHERN 2413 25 MTL 24030 N NORFOLK & WESTERN 391331 26 MTL 24240 N GULF, MOBILE & OHIO 21583 40' BXCR, SINGLE DOOR, NO ROOFWALK 27 $11.00 6231 MTL 25020 N MAINE CENTRAL 31011 50' RIB SIDE BXCR, SINGLE DR W/O ROOFWALK 28 MTL 25300 N ST. -

Rail Fmnt Catalog Visit

Rail FMnt Catalog visit: www.RailFonts.com Thank you for your interest in our selection of rail fonts and icons. They are an inexpensive way to turn your PC or Macintosh computer into a rail yard. About all you need to use the fonts is a computer and word processor (that's all I used to prepare this catalog). It's just that easy. For example, type "wsz" using the Freight font and in your document you get: wsz 99999999 On the other hand, if you typed, "ZSW" you would get: ZSW 99999999 (to add the track, just type "99999" on the next line) Thumbing through the catalog, you will find that most of the fonts fall into one of three categories: lettering similar to that used by the railroads, rolling stock silhouettes that couple together in your document, and rail clip-art. All of the silhouette fonts fit together, so you can create a real mixed train. Visit www.RailFonts.com to order the fonts or for more information. Benn Coifman CLIPART FONTS: UYxnFGHI Rail Art Font 1.0: This font is based on artwork from timetables, advertisements and other company publications during the golden age of railroading. rQwEA Sd f2l More Rail Art Font 1.0: This font is based on artwork from timetables, advertisements and other company publications during the golden age of railroading. zq8ialhEOd. LaGrange Font 1.2: This font captures the colorful styling of the EMD f-unit in its many faces. Over 50 different paint schemes included. Use the period or comma to add flags. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

qNPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior RECEIVED 2280 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places FEB 1 3 2008 Registration Form NA1r. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PUUCES NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties ar to Complete the National Register of Historic Places registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property __ ____________________________________ historic name Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio Railroad Station and Depot other names/site number CSX Train Depot 2. Location street & number 300 Buffalo Street ______ D not for publication N/A city or town Johnson City_____ __________ D vicinity N/A state Tennessee code TN county Washington code 179 zip code 37604 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property El meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Intermountain Railway Company 09/28/16 Item Stock List

2:23 PM InterMountain Railway Company 09/28/16 Item Stock List September 28, 2016 Item Description 25316HR O Assembled R-40-10 Steel Sided Ice Bunker - Pepper Packing Co. - High Rail 25316S O Assembled R-40-10 Steel Sided Ice Bunker - Pepper Packing Co. 26601HR O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - C B & Q - High Rail 26601S O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - C B & Q - Scale 26604HR O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - New York Central - High Rail 26604S O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - New York Central 26608HR O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - High Rail - Pennsylvania 26608S O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - Pennsylvania 26609HR O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - High Rail - Chesapeake & Ohio 26609S O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - Chesapeake & Ohio 26613HR O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - Frisco - High Rail 26613S O Assembled USRA Composite Drop Bottom Gondola - Frisco - Scale 30051 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - China Shipping - CCLU 30052 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Evergreen - EGHU 30053 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - K-Line - KKTU 30054 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Zim - ZIMU 30055 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Mediterranian Shipping - MSCU 30056 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Hanjin Shipping - HJCU 30057 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Cosco - CBHU 30058 HO Assembled A-Line 20' Container w/Corrugated Doors - Tropical - TTRU 30200 HO Kits 40' Corrugated Container - 2/pkg. -

Clinchfield Railroad: Elkhorn - St

Train Simulator – Clinchfield Railroad: Elkhorn - St. Paul Clinchfield Railroad: Elkhorn - St. Paul © Copyright Dovetail Games 2020, all rights reserved Release Version 1.0 Page 1 Train Simulator – Clinchfield Railroad: Elkhorn - St. Paul Contents 1 Route Map ............................................................................................................................................ 4 2 Rolling Stock ........................................................................................................................................ 5 3 Driving the GP7 .................................................................................................................................... 7 Cab Controls ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Key Layout .......................................................................................................................................... 8 4 Driving the F7 ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Cab Controls ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Key Layout ........................................................................................................................................ 10 5 Driving the SD40 ............................................................................................................................... -

B-1 John W Barriger III Papers Finalwpref.Rtf

A Guide to the John W. Barriger III Papers in the John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library A Special Collection of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis This project was made possible by a generous grant From the National Historical Publications and Record Commission an agency of the National Archives and Records Administration and by the support of the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri St. Louis © 1997 The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association i Preface and Acknowledgements This finding aid represents the fruition of years of effort in arranging and describing the papers of John W. Barriger III, one of this century’s most distinguished railroad executives. It will serve the needs of scholars for many years to come, guiding them through an extraordinary body of papers documenting the world of railroading in the first two-thirds of this century across all of North America. In every endeavor, there are individuals for whom the scope of their involvement and the depth of their participation makes them a unique participant in events of historical importance. Such was the case with John Walker Barriger III (1899-1976), whose many significant roles in the American railroad industry over almost a half century from the 1920s into the 1970s not only made him one of this century’s most important railroad executives, but which also permitted him to participate in and witness at close hand the enormous changes which took place in railroading over the course of his career. For many men, simply to participate in the decisions and events such as were part of John Barriger’s life would have been enough. -

The “Quick Service Route”—The Clinchfield Railroad

The “Quick Service Route”—the Clinchfield Railroad By Ron Flanary (all photos by the author) If you take a look at giant CSX Transportation’s map, you’ll see a rather strategic link that runs north- south through the heart of central Appalachia—western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia. To the current generation of railroaders, the combined 277 mile segments include one from Elkhorn City, Kentucky to Erwin, Tennessee known as the Kingsport Subdivision, plus the line south of there to Spartanburg, South Carolina, designated the Blue Ridge Subdivision. But, to those who have sufficient seniority to recall big 4-6-6-4s on fruit blocks (often double-headed with Mikes), matched sets of gray and yellow F-units urging full tonnage coal trains along heavy steel perched high on granite ballast, or black sided SDs working the mines along the Freemont Branch---this will always be “Clinchfield Country.” The blue and gray-flanked CSX high horsepower hoods that fleet the ceaseless caravan of coal trains and manifests through this striking setting today are engrossing—but not nearly so as the days of allure and sovereignty —when it was the Clinchfield. Efforts to link the deep water port of Charleston, South Carolina with the Midwest through this mountainous region date to as early as 1827. After earlier corporate efforts to translate vision into reality had failed, a regional icon named George L. Carter would eventually morph his fledgling South & Western Railroad into the Carolina, Clinchfield & Ohio---with completion of the through route consummated by the obligatory “last spike” ceremony (with Carter himself driving it home) at Trammel, Virginia in 1915. -

Whistle Stop April 2010

Whistle Stop Watauga Valley NRHS P O Box 432 Johnson City, TN. 37605-0432 (423) 753-5797 www.wataugavalleynrhs.org Railroading – Past, Present and Future Volume 30 No. 4 April 2010 Mike Jackson, Editor Duane and Harriet Swank, Printing/Circulation Next Chapter Meeting is April 26; See Page 3 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Gary Price, Keeping Norfolk Southern safe...one tie at a time 2010 Norfolk Southern Safety Awards Banquet This journey began for me early in 2009 when the Production Engineer from Atlanta toured our gang and told me that he liked my attitude and my dedication to the railroad. He said that when I discussed railroad issues, that I "spoke from the heart". He then asked me if I was interested in taking part in the yearly NS awards event held every March in Norfolk. Of course, I said yes, because I knew that NS pulls out the red carpet for this prestigious event. However it wasn't until February 2010 that I learned what my duties would be. I had been chosen to take the stage and announce all the safety award winners for the entire Maintenance of Way division. The event was held on March 9-10, 2010 at the Marriott Waterside Hotel in Norfolk. Considering the fact that Suzie had never seen the ocean, I decided to build a family vacation around this event. So we packed up the car and headed east until we ran out of land, and we exited into downtown Norfolk. The railroad provided us lodging for the first night, and I checked into the Sheraton Norfolk Waterfront on Tuesday March 9, 2010, grabbed a bite for lunch then headed across the street to the Marriott to register, pick up my name badge and itinerary, and find some familiar faces in a sea of employees. -

Presidential Documents 25131 Presidential Documents

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 97 / Friday, May 17, 1996 / Presidential Documents 25131 Presidential Documents Executive Order 13003 of May 15, 1996 Establishing an Emergency Board To Investigate Disputes Be- tween Certain Railroads Represented by the National Car- riers' Conference Committee of the National Railway Labor Conference and Their Employees Represented by the Brother- hood of Maintenance of Way Employes Disputes exist between certain railroads represented by the National Carriers' Conference Committee of the National Railway Labor Conference, including Consolidated Rail Corporation (including the Clearfield Cluster), Burlington Northern Railroad Co., CSX Transportation Inc., Norfolk Southern Railway Co., Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Co., Union Pacific Railroad, Chicago & North Western Railway Co., Kansas City Southern Railway Co., and their employees represented by the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employes. The railroads involved in these disputes are designated on the attached list, which is made a part of this order. The disputes have not heretofore been adjusted under the provisions of the Railway Labor Act, as amended (45 U.S.C. 151 et seq.) (the ``Act''). In the judgment of the National Mediation Board, these disputes threaten substantially to interrupt interstate commerce to a degree that would deprive a section of the country of essential transportation service. NOW, THEREFORE, by the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, including section 10 of the Act (45 U.S.C. 160), it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Establishment of Emergency Board (``Board''). There is established effective May 15, 1996, a Board of three members to be appointed by the President to investigate any and all of the disputes raised in mediation. -

N-Scale Master List

N SCALE DATABASE NEW # OLD # RR NAME OR NAME OF INIT RD # REL MSRP CAR COLOR 020 00 000 20000 Undecorated DATA n/a Nov-72 bcr with white lettering 020 00 000 20000 Dimensional data DATA n/a Mar-73 bcr with white lettering 020 00 001 20001 Dimensional data DATA n/a Nov-02 n/a bcr with white lettering 020 00 006 20006 Nickel Plate Road NKP 8502 Apr-90 $7.80 aluminum with black lettering 020 00 006 n/a Nickel Plate Road NKP 8505 Apr-06 $15.35 aluminum with black lettering 020 00 007 FRIEND New York Central NYC 161500 Mar-17 $26.95 Red with decorated sides 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516798 Nov-72 $7.80 bcr 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516768 Jul-90 $7.80 bcr 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516771 Dec-98 $10.75 bcr 020 00 016 20016 Nickel Plate Road NKP 13456 Jun-90 $7.80 bcr 020 00 017 FRIEND Union Pacific/Arkansas Rice UP 187989 Jul-17 $26.95 Brown with white/yellow 020 00 018 1972 #1 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516772 Nov-14 $19.95 brown with white lettering 020 00 020 20020 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe ATSF 144537 May-77 bcr 020 00 020 20020 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe ATSF 144572 Apr-86 bcr 020 00 022 20022 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe 5- ATSF multi May-77 see individual car listing 020 00 022 20022 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe 5- ATSF multi Apr-86 see individual car listing 020 00 026 20026 Seaboard Air Line SAL 17075 Sep-90 $8.40 bcr 020 00 027 FRIEND Southern Pacific n/a Sep-17 $26.95 Black with decorated sides 020 00 029 20029 New Haven NH 35149 Dec-72 bcr 020 00 029 20029 New Haven NH 35159 Feb-73 bcr -

Whistle Stop

Whistle Stop Watauga Valley Railroad Historical Society & Museum P. O. Box 432, Johnson City, TN. 37605-0432 (423) 753-5797 www.wataugavalleyrrhsm.org Preserving Our Region’s Railroad Heritage Volume 40 No. 9 September 2020 There’s quite a variety of rail traffic to be seen when viewing the Historic Chuckey Depot live webcam. Here we see Norfolk Southern's Geometry Train, with unit NS 38, commonly known as "The Brick", and research car NS 36 in tow. Colorful beams of light from the bottom of the cars take a digital profile of the track which is then used for future maintenance and upgrades. th August 24 General Membership Meeting Our next General Membership meeting will be held on Monday, August 24th , 2020 at 6:30 pm at the Chuckey Depot / Railroad Museum, 110 South Second St. Jonesborough, TN (at the railroad crossing). The program will be presented by Howard Orfield. To safeguard everyone’s health, face masks will be required and chairs will be spaced 6 feet apart to practice social distancing; also, the depot is cleaned during operating days and the building doors will be open. Mark your calendar so you will not miss this meeting and enjoyable evening with your fellow railfans. Whistle Stop September 2020 2 Member Notes Please keep Fred Phofl, the family of Nancy Jewell and Harold Smitter in your thoughts and prayers in their recent loss of loved ones. Keep George Ritchie, Gary Price, Art Devoe, Mike Dowdy and Billy Walker in your prayers as they deal with various health concerns. As always, let us know of any member, friend or family to whom a card might be sent or a phone call made. -

A Context of the Railroad Industry in Clark County and Statewide Kentucky

MAY 4, 2016 A CONTEXT OF THE RAILROAD INDUSTRY IN CLARK COUNTY AND STATEWIDE KENTUCKY CLARK COUNTY, KENTUCKY TECHNICAL REPORT 15028 15011 SUBMITTED TO: City of Winchester 32 Wall Street PO Box 40 Winchester, Kentucky 40392 10320 Watterson Trail Louisville KY 40299 502-614-8828 A CONTEXT OF THE RAILROAD INDUSTRY IN CLARK COUNTY AND STATEWIDE KENTUCKY OSA Project No. FY15-8453 KHC Project No. FY16-2211 Submitted to: Mr. Matt Belcher City Manager 32 Wall Street PO Box 40 Winchester, Kentucky 40392 859-744-6292 LEAD AGENCY: Federal Highway Administration Kentucky Transportation Cabinet Prepared By: Mathia N. Scherer, MA, Tim W. Sullivan, PhD, RPA, Kathryn N. McGrath, MA RPA, Anne Tobbe Bader, MA RPA, Sara Deurell, BA, and Michelle Massey, BA Corn Island Archaeology, LLC P.O. Box 991259 Louisville, Kentucky 40269 Phone (502) 614-8828 FAX (502) 614-8940 [email protected] Project No. PR15012 Cultural Resources Report No. TR15028 (Signature) Anne Bader Principal Investigator May 4, 2016 A Context of the Railroad Industry in Clark County and Statewide Kentucky ABSTRACT From April 2015 through April 2016 Corn Island Archaeology LLC researched and prepared a historic context for railroad and rail-related buildings, structures, objects, and archaeological resources in Kentucky with a particular focus on the City of Winchester and Clark County. Specifically, Corn Island prepared an inventory of known (recorded) railroad-related cultural resources within the proposed undertaking; assessed the potential for unrecorded railroad- related resources to be present in Clark County; and developed a historical context to allow informed interpretation of these resources as well as those that may be recorded in the future.