A Context of the Railroad Industry in Clark County and Statewide Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System

Under the Big Apple: a Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System by Emma Marie Waterloo This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Tomlan,Michael Andrew (Chairperson) Chusid,Jeffrey M. (Minor Member) UNDER THE BIG APPLE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF PRESERVATION PRACTICE AND THE NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY SYSTEM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Emma Marie Waterloo August 2010 © 2010 Emma Marie Waterloo ABSTRACT The New York City Subway system is one of the most iconic, most extensive, and most influential train networks in America. In operation for over 100 years, this engineering marvel dictated development patterns in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. The interior station designs of the different lines chronicle the changing architectural fashion of the aboveground world from the turn of the century through the 1940s. Many prominent architects have designed the stations over the years, including the earliest stations by Heins and LaFarge. However, the conversation about preservation surrounding the historic resource has only begun in earnest in the past twenty years. It is the system’s very heritage that creates its preservation controversies. After World War II, the rapid transit system suffered from several decades of neglect and deferred maintenance as ridership fell and violent crime rose. At the height of the subway’s degradation in 1979, the decision to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the opening of the subway with a local landmark designation was unusual. -

Two of the Wealthiest "Thrift Gardeners"

Two of the Wealthiest "Thrift Gardeners" in the United States These Holders of Many Thou- _? - sands of Acres Are Now Us- ing Them to Advantage In the Great WorM-Wide Cry for Food. BEN ALI HAGGIN has s 400,C00 acres of land in Kern county,- jjseen called the greatest breeder r California, containing some of the best JAMESof thoroughbred horses thatt farming land in the state. The metli- ever lived, the greatest farmer in Amer- - ods by which he got possession of this ica, and the greatest miner in the world. enormous tract subjected him to sharp Through these three pursuits, he has ac- - criticism but he later earned the grati- cumulated a fortune that is variously ? tudc of the farmers by carrying on, the estimated as "between $50,000,000 and 1 fight for irrigation privileges against' $100,000,000. He is certainly one of the the claims of the stock raisers. Had it wealthiest residents in the United States. not been for his single handed contest Few dukes of Great Britain possess in the courts, Southern California ,and as much He has one enormous the San Joaquin Valley would not* to- ranch of over 400,000 acres in Califor- day be such prosperous communities. nia, another of 8,000 acres in the heart Haggin is perhaps best known, how- of the Blue Grass region of Kentucky, ever, for" his work as a breeder of and one of the most palatial residence.! thoroughbred horses. Within 10 years, on Fifth avenue, New York. He owns his colors had flashed past the wire as large interests in mines extending from 1 winners of practically every important Alaska on the north to Chili in the ! ' stake in the country. -

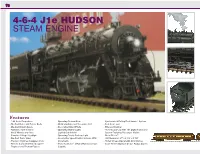

4-6-4 J1e HUDSON STEAM ENGINE

76 4-6-4 J1e HUDSON STEAM ENGINE Features - 1:48 Scale Proportions - Operating Firebox Glow - Synchronized Puffing ProtoSmoke® System - Die-Cast Boiler and Tender Body - Metal Handrails and Decorative Bell - Real Coal Load - Die-Cast Metal Chassis - Decorative Metal Whistle - Wireless Drawbar - Authentic Paint Scheme - Operating Marker Lights - Proto-Sound® 2.0 With The Digital Command - Metal Wheels and Axles - Lighted Cab Interior System Featuring Passenger Station - Constant Voltage Headlight - Operating Tender Back-up Light Proto-Effects™ - Die-Cast Truck Sides - Locomotive Speed Control in Scale MPH - Unit Measures: 27” x 2 1/2” x 3 7/8” - Precision Flywheel Equipped Motor Increments - Hi-Rail Wheels Operate On O-42 Curves - Remote Controlled Proto-Coupler™ - Proto-Scale 3-2™ 3-Rail/2-Rail Conversion - Scale Wheels Operate On 42” Radius Curves - Engineer and Fireman Figures Capable 77 In Thoroughbreds, Alvin Staufer and Edward May's definitive book on the New York Central Hudsons, Al summarizes the attraction of this engine in a few perhaps-biased but nonetheless eloquent words: "The Hudsons had it all: looks, performance, and timing. … [The] forte of all Hudsons was power at speed…. That [the NYC Hudson] was the first of her Iwheel arrangement in the United States matters not New York Central - 4-6-4 J1e Hudson Steam Engine nearly as much as what she hauled and how she 20-3321-1 w/Proto-Sound 2.0 (Hi-Rail Wheels) $999.95 hauled it. The Hudsons were designed to haul the 20-3321-2 w/Proto-Sound 2.0 (Scale Wheels) $999.95 Great Steel Fleet on the Water Level Route [the NYC's raceway from New York to Chicago, home of the 20th Century Limited and the Empire State Express, and the bane of rival Pennsylvania Railroad, whose route lay over the Allegheny Mountains]. -

Aances, Etc. , O T E Nite Tates

Combined Statement OF THE eceipts an is ursements, aances, etc. , o t e nite tates DURING THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30 OFFICE O~ SECR~ WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE TREASURT DEPARTMENT. Document No. 2815. Dfefdon og Bookkeeping and Warrants. RECEIPTS AND DISBURSEMENTS, BALANCES, ETC. LETTER FROM THE SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY, TRANSMITTING A Combined Statement of the Receipts and Disbursements, Balances, etc. , of the Government During the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1917. TREASURY DEPARTMENT) OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY) Washington, D. O. , December 8, 191'1 TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. SIR: In compliance with the requirements of section 15 of an act entitled "An act making appropriations for the legislative, "executive, and judicial expenses of the Government for the fIscal year ending June 30, 1895, and for other purposes, approved July 31, 1894 (28 Stat. , p. 210), I have the honor to transmit herewith a combined state- ment of the receipts and disbursements, balances, etc. , of the Government during the fiscal year ended June 30, 1917. Respectfully, W G. McAnoo, secretary. 3 COMBINED STATEMENT OF THE RECEIPTS AND DISBURSEMENTS, BALANCES, ETC., OF THE UNITED STATES DURING THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 1917. (Details of Receipts on pp. 7 to 25, and of Disbursements on pp. 26 to 181.) TREASURY DEPARTMENT, DIVISION OF BOOKKEEPING AND WARRANTS. SIR: I have the honor to submit herewith statements of the receipts and disbursements of the Government during the fiscal year ended June 30, 1917, as fo)lows: Excess of receipts (+), Cisss. Receipts. Disbursements. excess of disburse- ments ( —). Ordinary . $1, 118, 174, 126. -

Railroads in Muncie, Indiana Author Michael L. Johnston May 1, 2009

Railroads in Muncie 1 Running Head: RAILROADS IN MUNCIE Railroads in Muncie, Indiana Author Michael L. Johnston May 1, 2009 Copyright 2009. M. L. Johnston. All rights reserved. Railroads in Muncie 2 Running Head: Railroads in Muncie Abstract Railroads in Muncie, Indiana explains the evolution of railroads in Muncie, and Delaware County, Indiana. Throughout the history of the United States, the railroad industry has been a prominent contributor to the development and growth of states and communities. Communities that did not have railroads did not develop as competitively until improvements in roads and highways gave them access to an alternative form of transportation. This manuscript provides a brief overview of the history and location of the railroads in Muncie and their importance to the growth of the community. Copyright 2009. M. L. Johnston. All rights reserved. Railroads in Muncie 3 Running Head: Railroads in Muncie Railroads in Muncie, Indiana Evolution of the U.S. Railroad Industry The U.S. railroad industry started around 1810 in the East. After the Civil War, railroad construction was rampant and often unscrupulous. Too many railroad lines were built that were under-capitalized, poorly constructed, and did not have enough current business to survive. Monopolistic and financial abuses, greed and political corruption forced government regulations on the railroads. From 1887 until 1980 the federal Interstate Commerce Commission strictly regulated economics and safety of all railroads operating in the U.S. Until 1980 the various states, also, regulated economics and safety of railroad companies within their individual state boundaries. Railroads are privately owned and the federal government considers them to be common carriers for the benefit of the public. -

UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS COUNSEL for the SIXTH CIRCUIT ARGUED: Donald L

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 2 Martingale LLC, et al. v. City of No. 02-5895 ELECTRONIC CITATION: 2004 FED App. 0080P (6th Cir.) Louisville, et al. File Name: 04a0080p.06 _________________ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS COUNSEL FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT ARGUED: Donald L. Cox, LYNCH, COX, GILMAN & _________________ MAHAN, Louisville, Kentucky, for Appellants. John L. Tate, STITES & HARBISON, Louisville, Kentucky, for MARTINGALE LLC; BRIDGE X Appellees. ON BRIEF: Donald L. Cox, William H. THE GAP, INC., - Mooney, LYNCH, COX, GILMAN & MAHAN, Louisville, - Plaintiffs-Appellants, Kentucky, Theodore L. Mussler, Jr., MUSSLER & - No. 02-5895 ASSOCIATES, Louisville, Kentucky, for Appellants. John - L. Tate, Emily R. Hartlage, STITES & HARBISON, v. ,> Louisville, Kentucky, for Appellees. - CITY OF LOUISVILLE; - _________________ - WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT OPINION CORPORATION, - - _________________ Defendants-Appellees. - N JAMES S. GWIN, District Judge. In this case, Martingale, LLC (“Martingale”) and Bridge the Gap, Inc. (“Bridge the Appeal from the United States District Court Gap”) appeal the district court’s ruling permitting the City of for the Western District of Kentucky at Louisville. Louisville (“City”) and the Waterfront Development No. 01-00255—Charles R. Simpson, III, District Judge. Corporation to condemn a structure known as the Big Four Bridge. The Big Four Bridge connects Jeffersonville, Indiana Argued: October 22, 2003 with Louisville, Kentucky. The City and the Waterfront Development Corporation wish to use the bridge as part of a Decided and Filed: March 17, 2004 public park, but Martingale and Bridge the Gap contend that the City has no legal power to condemn the bridge. Before: BOGGS, Chief Judge; GIBBONS, Circuit Judge; GWIN, District Judge.* For the following reasons, the district court’s decision is AFFIRMED. -

D. Rail Transit

Chapter 9: Transportation (Rail Transit) D. RAIL TRANSIT EXISTING CONDITIONS The subway lines in the study area are shown in Figures 9D-1 through 9D-5. As shown, most of the lines either serve only portions of the study area in the north-south direction or serve the study area in an east-west direction. Only one line, the Lexington Avenue line, serves the entire study area in the north-south direction. More importantly, subway service on the East Side of Manhattan is concentrated on Lexington Avenue and west of Allen Street, while most of the population on the East Side is concentrated east of Third Avenue. As a result, a large portion of the study area population is underserved by the current subway service. The following sections describe the study area's primary, secondary, and other subway service. SERVICE PROVIDED Primary Subway Service The Lexington Avenue line (Nos. 4, 5, and 6 routes) is the only rapid transit service that traverses the entire length of the East Side of Manhattan in the north-south direction. Within Manhattan, southbound service on the Nos. 4, 5 and 6 routes begins at 125th Street (fed from points in the Bronx). Local service on the southbound No. 6 route ends at the Brooklyn Bridge station and the last express stop within Manhattan on the Nos. 4 and 5 routes is at the Bowling Green station (service continues into Brooklyn). Nine of the 23 stations on the Lexington Avenue line within Manhattan are express stops. Five of these express stations also provide transfer opportunities to the other subway lines within the study area. -

NSC 2020 Early March Auction Results

MFG MODEL SCALE ROADNAME ROAD # VARIATION # PRICE MEMBER MTL 20090 N SOUTHERN PACIFIC 97947 SINGLE CAR 1 MTL 20170 N BURLINGTON-CB&Q 62988 WZ @ BW 2 MTL 20240 N NEW YORK CENTRAL 174710 PACEMAKER 3 MTL 20240 N NEW YORK CENTRAL 174710 PACEMAKER 4 $11.00 6231 MTL 20630 N WEST INDIA FRUIT 101 5 $19.00 5631 MTL 20850 N SPOKANE, PORTLAND & SEATTLE 12218 6 MTL 20880 N LAKE SUPERIOR & ISHPEMING 2290 7 $14.00 1687 MTL 20880 N LAKE SUPERIOR & ISHPEMING 2290 7 $14.00 6258 MTL 20950 N CHICAGO GREAT WESTERN 90017 8 MTL 20970 N PACIFIC GREAT EASTERN 4022 9 $14.00 1687 MTL 20066 N PENNSYLVANIA 30902 "MERCHANDISE SERVICE" 10 MTL 20086 N MICROTRAINS LINE COMPANY 1991 1ST ANNIVERSARY 11 MTL 20126 N LEHIGH VALLEY 62545 12 $10.00 2115 MTL 20186 N GREAT NORTHERN 19617 CIRCUS CAR #7 -RED 13 MTL 20306/2 N BURLINGTON NORTHERN 189288 14 MTL 20346 N BALTIMORE & OHIO 470687 "TIMESAVER" 15 MTL 20346-2 N BALTIMORE & OHIO 470751 16 MTL 20486 N MONON 861 "THE HOOSIER LINE" 17 $18.00 6258 MTL 21020 N STATE OF MAINE 2231 40' STANDARD BXCR, PLUG DOOR 18 MTL 21040 N GREAT NORTHERN 7136 40' STANDARD BXCR, PLUG DOOR 19 $19.00 2115 MTL 21212 N BURLINGTON NORTHERN 4-PACK "FALLEN FLAGS #03 20 MTL 21230 N BRITISH COLUMBIA RAILWAY 8002 21 MTL 22030 N UNION PACIFIC 110013 22 MTL 22180 N MILWAUKEE 29960 23 MTL 23230 N UNION PACIFIC 9149 "CHALLENGER" 24 $24.00 4489 MTL 23240 N ASHLEY, DREW & NORTHERN 2413 25 MTL 24030 N NORFOLK & WESTERN 391331 26 MTL 24240 N GULF, MOBILE & OHIO 21583 40' BXCR, SINGLE DOOR, NO ROOFWALK 27 $11.00 6231 MTL 25020 N MAINE CENTRAL 31011 50' RIB SIDE BXCR, SINGLE DR W/O ROOFWALK 28 MTL 25300 N ST. -

October 2017

May 2017 Error! No text of specified style in document. fff October 2017 September 2016 E r r o r ! No text of specified style in document. | i Indiana State Rail Plan Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ S-1 S.1 PURPOSE OF THE INDIANA STATE RAIL PLAN .................................................................................................. S-1 S.2 VISION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................. S-1 S.3 INDIANA RAIL NETWORK ............................................................................................................................ S-3 S.4 PASSENGER RAIL ISSUES, OPPORTUNITIES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS AND IMPROVEMENTS ................................... S-7 S.5 SAFETY/CROSSING ISSUES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS AND IMPROVEMENTS ....................................................... S-9 S.6 FREIGHT RAIL ISSUES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS, AND IMPROVEMENTS .............................................................. S-9 S.7 RAIL SERVICE AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM ................................................................................................ S-12 1 THE ROLE OF RAIL IN STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION (OVERVIEW) ................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE AND CONTENT .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 MULTIMODAL -

California's Groundwater: a Political Economy

California’s Groundwater: A Political Economy John Ferejohn NYU Law February 2017 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 1. Nuts 8 2. Groundwater 11 3. From Political Economy to Industrial Organization 19 4. Early History 24 5. Water Law: Courts v. Legislature 30 6. Groundwater Regulation 43 7. Federal and State Water Projects 52 8. Environmental Revolution 73 9. Drought 87 10. Political Opportunities 100 2 “...Annie Cooper was looking outside her kitchen window at another orchard of nuts going into the ground. This one was being planted right across the street. Before the trees even arrived, the big grower – no one from around here seems to know his name – turned on the pump to test his new deep well, and it was at that precise moment, Annie says, when the water in his plowed field gushed like flood time, that the Coopers’ house went dry.”1 Introduction Many suppose that Annie Cooper’s story is emblematic of California’s water problem. Often the culprit is named – almonds, pistachios, walnuts – each of which is very profitable to farm in California and is water hungry. It is true that California Almond growers supply 80% of the worldwide supply despite severe drought conditions in recent years. In 2015 a story in the Sacramento Bee reported that “the amount of California farmland devoted to almonds has nearly doubled over the past 20 years, to more than 900,000 acres.” Similar increases have been experienced by other nut crops (pistachios, walnuts, etc). There is no question therefore that there has been an immense change Central Valley agriculture. -

Chapter 11 ) LAKELAND TOURS, LLC, Et Al.,1 ) Case No

20-11647-jlg Doc 205 Filed 09/30/20 Entered 09/30/20 13:16:46 Main Document Pg 1 of 105 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) LAKELAND TOURS, LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 20-11647 (JLG) ) Debtors. ) Jointly Administered ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Julian A. Del Toro, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On September 25, 2020, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B, and on three (3) confidential parties not listed herein: Notice of Filing Third Amended Plan Supplement (Docket No. 200) Notice of (I) Entry of Order (I) Approving the Disclosure Statement for and Confirming the Joint Prepackaged Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization of Lakeland Tours, LLC and Its Debtor Affiliates and (II) Occurrence of the Effective Date to All (Docket No. 201) [THIS SPACE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK] ________________________________________ 1 A complete list of each of the Debtors in these chapter 11 cases may be obtained on the website of the Debtors’ proposed claims and noticing agent at https://cases.stretto.com/WorldStrides. The location of the Debtors’ service address in these chapter 11 cases is: 49 West 45th Street, New York, NY 10036. 20-11647-jlg Doc 205 Filed 09/30/20 Entered 09/30/20 13:16:46 Main Document Pg 2 of 105 20-11647-jlg Doc 205 Filed 09/30/20 Entered 09/30/20 13:16:46 Main Document Pg 3 of 105 Exhibit A 20-11647-jlg Doc 205 Filed 09/30/20 Entered 09/30/20 13:16:46 Main Document Pg 4 of 105 Exhibit A Served via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country Aaron Joseph Borenstein Trust Address Redacted Attn: Benjamin Mintz & Peta Gordon & Lucas B. -

Rail Fmnt Catalog Visit

Rail FMnt Catalog visit: www.RailFonts.com Thank you for your interest in our selection of rail fonts and icons. They are an inexpensive way to turn your PC or Macintosh computer into a rail yard. About all you need to use the fonts is a computer and word processor (that's all I used to prepare this catalog). It's just that easy. For example, type "wsz" using the Freight font and in your document you get: wsz 99999999 On the other hand, if you typed, "ZSW" you would get: ZSW 99999999 (to add the track, just type "99999" on the next line) Thumbing through the catalog, you will find that most of the fonts fall into one of three categories: lettering similar to that used by the railroads, rolling stock silhouettes that couple together in your document, and rail clip-art. All of the silhouette fonts fit together, so you can create a real mixed train. Visit www.RailFonts.com to order the fonts or for more information. Benn Coifman CLIPART FONTS: UYxnFGHI Rail Art Font 1.0: This font is based on artwork from timetables, advertisements and other company publications during the golden age of railroading. rQwEA Sd f2l More Rail Art Font 1.0: This font is based on artwork from timetables, advertisements and other company publications during the golden age of railroading. zq8ialhEOd. LaGrange Font 1.2: This font captures the colorful styling of the EMD f-unit in its many faces. Over 50 different paint schemes included. Use the period or comma to add flags.