Rastafarians and Orthodoxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

Mysticism and Greek Monasticism

Mysticism and Greek Monasticism By JOHANNES RINNE There is reason to assert that Christian mysticism is as old as Christianity itself. In the Pauline epistles, e.g., there are obvious signs of this fact. The later Christian mysticism has, in a high degree, been inspired by these ele- ments and likewise by various corresponding thoughts in the Johannine writings, which traditionally are interpreted from this angle and which have played a central role especially for the Orthodox Church.' In the light of the above-mentioned circumstances, it seems fully natural that there exists, from the very beginning, a clear connection also between mysticism and Christian monasticism. It has been pointed out by certain authors that the role of mystical visions is of essential and decisive significance also as regards the development from the stage of the hermits of the deserts to that form of life which, in the proper sense of the word, is characterised as monastic. There is, generally speaking, no possibility to understand correctly the intentions and the thoughts of the great pioneers of monasticism, unless one takes into account the mystically visionary factors. To this end it is neces- sary, furthermore, to penetrate in an inner, spiritual way, into the holy sym- bolism of the monastic tradition and into the sacred legends of its history.2 In other words, it is necessary to keep constantly in mind the visionary factor and to remember that the pioneers of monastic life, as a rule, are men of which it may be said that they have their conversation in heaven: on the mystical level of vision they converse with the angels as the representatives of the heavenly world and as those organs, by means of which the principles of monastic life are transmitted and given to the men of mystical visions.' The things mentioned above are not merely history. -

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley's “Love Created I”

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley’s “Love Created I” Darren J. N. Middleton Texas Christian University f art is the engine that powers religion’s vehicle, then reggae music is the 740hp V12 underneath the hood of I the Rastafari. Not all reggae music advances this movement’s message, which may best be seen as an anticolonial theo-psychology of black somebodiness, but much reggae does, and this is because the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley OM, aka Tuff Gong, took the message as well as the medium and left the Rastafari’s track marks throughout the world.1 Scholars have been analyzing such impressions for years, certainly since the melanoma-ravaged Marley transitioned on May 11, 1981 at age 36. Marley was gone too soon.2 And although “such a man cannot be erased from the mind,” as Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga said at Marley’s funeral, less sanguine critics left others thinking that Marley’s demise caused reggae music’s engine to cough, splutter, and then die.3 Commentators were somewhat justified in this initial assessment. In the two decades after Marley’s tragic death, for example, reggae music appeared to abandon its roots, taking on a more synthesized feel, leading to electronic subgenres such as 1 This is the basic thesis of Carolyn Cooper, editor, Global Reggae (Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press, 2012). In addition, see Kevin Macdonald’s recent biopic, Marley (Los Angeles, CA: Magonlia Home Entertainment, 2012). DVD. 2 See, for example, Noel Leo Erskine, From Garvey to Marley: Rastafari Theology (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); Dean MacNeil, The Bible and Bob Marley: Half the Story Has Never Been Told (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013); and, Roger Steffens, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, with an introduction by Linton Kwesi Johnson (New York and London: W.W. -

O. Lake the Many Voices of Rastafarian Women

O. Lake The many voices of Rastafarian women : sexual subordination in the midst of liberation Author calls it ironic that although Rasta men emphasize freedom, their relationship to Rasta women is characterized by a posture and a rhetoric of dominance. She analyses the religious thought and institutions that reflect differential access to material and cultural resources among Rastafarians. Based on the theory that male physical power and the cultural institutions created by men set the stage for male domination over women. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 68 (1994), no: 3/4, Leiden, 235-257 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 06:46:12PM via free access OBIAGELE LAKE THE MANY VOICES OF RASTAFARIAN WOMEN: SEXUAL SUBORDINATION IN THE MIDST OF LIBERATION Jamaican Rastafarians emerged in response to the exploitation and oppres- sion of people of African descent in the New World. Ironically, although Rasta men have consistently demanded freedom from neo-colonialist forces, their relationship to Rastafarian women is characterized by a pos- ture and a rhetoric of dominance. This discussion of Rastafarian male/ female relations is significant in so far as it contributes to the larger "biology as destiny" discourse (Rosaldo & Lamphere 1974; Reiter 1975; Etienne & Leacock 1980; Moore 1988). While some scholars claim that male dom- ination in indigenous and diaspora African societies results from Ëuropean influence (Steady 1981:7-44; Hansen 1992), others (Ortner 1974; Rubin 1975; Brittan 1989) claim that male physical power and the cultural institu- tions created by men, set the stage for male domination over women in all societies. -

Religious Studies Humanities Division We Understand the Study of Religion As a Crucial Element in the Larger Study of Culture and History

Kenyon College Course Catalog 2019-20 Requirements: Religious Studies Humanities Division We understand the study of religion as a crucial element in the larger study of culture and history. We consider the study of religion to be inherently interdisciplinary and a necessary component for intercultural literacy and, as such, essential to the liberal arts curriculum. Our goals include helping students to recognize and examine the important role of religion in history and the contemporary world; to explore the wide variety of religious thought and practice, past and present; to develop methods for the academic study of particular religions and religion in comparative perspective; and to develop the necessary skills to contribute to the ongoing discussion of the nature and role of religion. Since the phenomena that we collectively call "religion" are so varied, it is appropriate that they be studied from a variety of theoretical perspectives and with a variety of methods. The diversity of areas of specialization and approaches to the study of religion among our faculty members ensures the representation of many viewpoints. Our courses investigate the place of religion in various cultures in light of social, political, economic, philosophical, psychological and artistic questions. We encourage religious studies majors to take relevant courses in other departments. The Department of Religious Studies maintains close relationships with interdisciplinary programs such as Asian and Middle East studies, American studies, African diaspora studies, international studies, and women's and gender studies. Our courses require no commitment to a particular faith. However, students of any background, secular or religious, can benefit from the personal questions of meaning and purpose that arise in every area of the subject. -

JAH PEOPLE: the CULTURAL HYBRIDITY of WHITE RASTAFARIANS for More Than Half a Century, the African-Based, Ras- Tafarian Movement

JAH PEOPLE: THE CULTURAL HYBRIDITY OF WHITE RASTAFARIANS MICHAEL LOADENTHAL School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution George Mason University [email protected] Abstract: For more than half a century, the African-based Rastafarian movement has existed and thrived. Since the early 1930s, Rastafari has developed, changed and gained enough supporters to be considered “one of the most popular Afro- Caribbean religions of the late twentieth century. According to a survey con- ducted in 1997, there are over one million practicing Rastafarians worldwide as well as over two million sympathizers. Rastafarians are concentrated in the Car- ibbean, though members of this diverse movement have settled in significant numbers all throughout the world. At present, there are large Rastafarian com- munities in New York, Miami, Washington DC, Philadelphia, Chicago, Huston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston and New Haven as well as many large cities in Canada, Europe, South America and Africa. While Rastafari has maintained much of its original flavour, migration, globalization and a reinterpretation of philosophical dogma has created a space for white people to join this typically black movement. Keywords: hybridity, Rastafarians, religions, migration, political movement. INTRODUCTION For more than half a century, the African-based, Ras- tafarian movement has existed and thrived. Since the ear- ly 1930s, Rastafari has developed, changed and gained enough supporters to be considered “one of the most popular Afro-Caribbean religions of the late twentieth century” (Murrell 1998, 1). According to a survey con- ducted in 1997, there are over one million practicing Ras- tafarians worldwide as well as over two million sympa- thizers. -

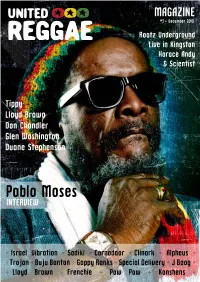

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

The Rastafarian Movement in Jamaica Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bakalářská diplomová práce Michal Šilberský Michal 2010 Michal Šilberský 20 10 10 Hřbet Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Michal Šilberský The Rastafarian Movement in Jamaica Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph. D. 2010 - 2 - I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature - 3 - I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Martina Horáková, Ph.D. for her helpful advice and the time devoted to my thesis. - 4 - Table of Contents 1. Introduction 6 2. History of Jamaica 8 3. The Rastafarian Movement 13 3.1. Origins 13 3.2. The Beginnings of the Rastafarian Movement 22 3.3. The Rastafarians 25 3.3.1. Dreadlocks 26 3.3.2. I-tal 27 3.3.3. Ganja 28 3.3.4. Dread Talk 29 3.3.5. Ethiopianism 30 3.3.6. Music 32 3.4. The Rastafarian Movement after Pinnacle 35 4. The Influence of the Rastafarian Movement on Jamaica 38 4.1. Tourism 38 4.2. Cinema 41 5. Conclusion 44 6. Bibliography 45 7. English Resumé 48 8. Czech Resumé 49 - 5 - 1. Introduction Jamaica has a rich history of resistance towards the European colonization. What started with black African slave uprisings at the end of the 17th century has persisted till 20th century in a form of the Rastafarian movement. This thesis deals with the Rastafarian movement from its beginnings, to its most violent period, to the inclusion of its members within the society and shows, how this movement was perceived during the different phases of its growth, from derelicts and castaways to cultural bearers.