Nº De Aluna: 26055 CHINA's SPACE PROGRAM: a NEW TOOL FOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules for the Heavens: the Coming Revolution in Space and the Laws of War

RULES FOR THE HEAVENS: THE COMING REVOLUTION IN SPACE AND THE LAWS OF WAR John Yoo* Great powers are increasing their competition in space. Though Russia and the United States have long relied on satellites for surveillance of rival nations’ militaries and the detection of missile launches, the democratization of space through technological advancements has allowed other nations to assert greater control. This Article addresses whether the United States and other nations should develop the space-based weapons that these policies promise, or whether they should cooperate to develop new international agreements to ban them. In some areas of space, proposals for regulation have already come too late. The U.S.’s nuclear deterrent itself depends cru- cially on space: ballistic missiles leave and then re-enter the atmosphere, giving them a global reach without serious defense. As more nations develop nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) technology, outer space will become even more important as an arena for defense against weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation. North Korea’s progress on ICBM and nuclear technology, for example, will prompt even greater in- vestment in space-based missile defense systems. This Article makes two contributions. First, it argues against a grow- ing academic consensus in favor of a prohibition on military activities in space. It argues that these scholars over-read existing legal instruments and practice. While nations crafted international agreements to bar WMDs in outer space, they carefully left unregulated reconnaissance and commu- nications satellites, space-based conventional weapons, antisatellite sys- tems, and even WMDs that transit through space, such as ballistic missiles. -

China's Space Industry and International Collaboration

China’s Space Industry and International Collaboration Presenter: Ju Jin Title: Minister Counselor,the Embassy of P.R.China Date: Feb 27,2008 Brief History • 52 years since 1956, first space institute established • Learning from Soviet Union until 1960 • U.S.A.’s close door policy until now • China’s self-reliance Policy Major Achievements • 12 series of Long March Launching Rockets • >100 Launches • >80 satellites in remote sensing, telecommunication, GPS, scientific experiment • Manned space flights——Shenzhou 5 (2003) and Shenzhou 6 (2005) • Lunar Exploration Project——Chang’e 1 (2007) LM-2F Launch Vehicle • Stages 1 & 2 & 4 strap-on boosters • 58.3 meters long • Launch Mass: 480 tons • Total Thrust : 600 tons • Reliability & Safety Index: 0.97 & 0.997 • 10 Sub-Systems Manned Space Flight--Shenzhou 6 Manned Space Flight--Shenzhou 6 Lunar Probe Project--Change-1 First Lunar Surface Photos Lunar Probe Project—Change 1 • 3 Years • 17,000 Scientists and Engineers • Young Team averaged in the age of 30s • 100% China-Made • Technology Breakthroughs – All-direction Antenna – Ultra-violet Sensor International Exchange and Cooperation: Main Activities Over the recent years, China has signed cooperation agreements on the peaceful use of outer space and space project cooperation agreements with Argentina, Brazil, Canada, France, Malaysia, Pakistan, Russia, Ukraine, the ESA and the European Commission, and has established space cooperation subcommittee or joint commission mechanisms with Brazil, France, Russia and Ukraine. China and the ESA z Sino-ESA Double Star Satellite Exploration of the Earth's Space Plan. z "Dragon Program," involving cooperation in Earth observation satellites, having so far conducted 16 remote-sensing application projects in the fields of agriculture, forestry, water conservancy, meteorology, oceanography and disasters. -

China's Space Program

China’s Space Program An Introduction China’s Space Program ● Motivations ● Organization ● Programs ○ Satellites ○ Manned Space flight ○ Lunar Exploration Program ○ International Relations ● Summary China’s Space Program Motivations Stated Purpose ● Explore outer space and to enhance understanding of the Earth and the cosmos ● Utilize outer space for peaceful purposes, promote human civilization and social progress, and to benefit the whole of mankind ● Meet the demands of economic development, scientific and technological development, national security and social progress ● Improve the scientific and cultural knowledge of the Chinese people ● Protect China's national rights and interests ● Build up China’s national comprehensive strength National Space Motivations • Preservation of its political system is overriding goal • The CCP prioritizes investments into space technology ○ Establish PRC as an equal among world powers ○ Space for international competition and cooperation ○ Manned spaceflight ● Foster national pride ● Enhance the domestic and international legitimacy of the CCP. ○ Space technology is metric of political legitimacy, national power, and status globally China’s Space Program Organization The China National Space Administration (CNSA) ● The China National Space Administration (CNSA, GuóJiā HángTiān Jú,) ○ National space agency of the People's Republic of China ○ Responsible for the national space program. ■ Planning and development of space activities. The China National Space Administration ● CNSA and China Aerospace -

Introduction

Introduction The Georgia Historical Society is excited to offer “And That’s the Way It Is: Television and the Cold War” inquiry kit. This inquiry-based resource includes activities designed to meet the Georgia Standards of Excellence for fifth grade U.S. history. Based on the Inquiry Design Model from C3 Teachers, this resource explores primary sources and utilizes relevant strategies to investigate the Cold War era of the late 20th Century in Georgia and the United States by focusing on the rise of mass media and its relationship to the Cold War including events such as the Vietnam War, the Space Race, and the Civil Rights Movement. The contents of the Inquiry Kit are a series of inquiry-based strategies and activities designed to help teachers guide students to explore a curated set of primary sources. The inquiry format is based on the Inquiry Design Model (IDM) from the C3 Framework for the Social Studies. The inquiry element emphasized in the C3 Framework is centered on asking a compelling question. Compelling questions are meant to address issues found across the social studies disciplines. They engage students by evoking their interests and highlighting the content with which students might have little experience. For example, the compelling question in the “And That’s the Way It Is: Television and the Cold War” inquiry kit “How was the Cold War shaped by television?” The compelling question is open-ended and is meant to engage students in critical thinking and creativity. It challenges students to examine the focus-of-study, the Cold War, through a multi-disciplinary lens. -

China Manned Space Programme

China Manned Space Programme Xiaobing Zhang Deputy Director Scientific Planning Bureau China Manned Space Agency [email protected] June 2015 58’COPUOS@Vienna China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 1 Content ° Introduction to development strategy ° Achievements up to date ° China’s space station and its latest development ° International cooperation ° Conclusion China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 2 Part I: Development strategy ° In 1992, the Chinese government approved the launch of China’s manned space programme ° Formulated the “three-step strategy” to implement the Programme China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 3 Three-step strategy 3rd step : To construct China’s space station to accommodate long-term man-tended utilization on a large scale The 2 nd step : To launch space labs to make technological breakthrough in EVA, R&D, and accommodation of long- term man-tended utilization on a modest scale The 1 st step: To launch manned spaceships to master the basic human space technology China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 4 Part II: Achievements up to date ° Unmanned spaceflight missions – SZ-1, 20 Nov 1999, 1 st unmanned spaceflight – SZ-2, 10 Jan 2001, 2 nd unmanned spaceflight SZ-1 SZ-2 – SZ-3, 25 Mar 2002, 3 rd unmanned spaceflight – SZ-4, 30 Dec 2002, 4 th unmanned spaceflight SZ-3 SZ-4 ° Achieved goals: – Laying a solid foundation for manned missions China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 5 ° Manned spaceflight missions – Basic Human Spaceflights Shenzhou-5, 2003, 1 st manned spaceflight mission Shenzhou-6, 2005, 1 st multiple-crew -

The Influence of Space Power Upon History (1944-1998)*

* The Influence of Space Power upon History (1944-1998) by Captain John Shaw, USAF * My interest in this subject grew during my experiences as an Air Force Intern 1997-98, working in both the Office of the Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Space, and in SAF/AQ, Space and Nuclear Deterrence Directorate. I owe thanks to Mr. Gil Klinger (acting DUSD(Space)) and BGen James Beale (SAF/AQS) for their advice and guidance during my internships. Thanks also to Mr. John Landon, Col Michael Mantz, Col James Warner, Lt Col Robert Fisher, and Lt Col David Spataro. Special thanks to Col Simon P. Worden for his insight on this topic. A primary task of the historian is to interpret events in the course of history through a unique lens, affording the scholar a new, and more intellectually useful, understanding of historical outcomes. This is precisely what Alfred Thayer Mahan achieved when he wrote his tour de force The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1660-1783). He interpreted the ebb and flow of national power in terms of naval power, and his conclusions on the necessity of sea control to guarantee national welfare led many governments of his time to expand their naval capabilities. When Mahan published his work in 1890, naval power had for centuries already been a central determinant of national military power.1 It remained so until joined, even eclipsed, by airpower in this century. Space, by contrast, was still the subject of extreme fiction a mere one hundred years ago, when Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H.G. -

India and China Space Programs: from Genesis of Space Technologies to Major Space Programs and What That Means for the Internati

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 India And China Space Programs: From Genesis Of Space Technologies To Major Space Programs And What That Means For The Internati Gaurav Bhola University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Bhola, Gaurav, "India And China Space Programs: From Genesis Of Space Technologies To Major Space Programs And What That Means For The Internati" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4109. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4109 INDIA AND CHINA SPACE PROGRAMS: FROM GENESIS OF SPACE TECHNOLOGIES TO MAJOR SPACE PROGRAMS AND WHAT THAT MEANS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY by GAURAV BHOLA B.S. University of Central Florida, 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2009 Major Professor: Roger Handberg © 2009 Gaurav Bhola ii ABSTRACT The Indian and Chinese space programs have evolved into technologically advanced vehicles of national prestige and international competition for developed nations. The programs continue to evolve with impetus that India and China will have the same space capabilities as the United States with in the coming years. -

Highlights in Space 2010

International Astronautical Federation Committee on Space Research International Institute of Space Law 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren c/o CNES 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren UNITED NATIONS 75015 Paris, France 2 place Maurice Quentin 75015 Paris, France Tel: +33 1 45 67 42 60 Fax: +33 1 42 73 21 20 Tel. + 33 1 44 76 75 10 E-mail: : [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax. + 33 1 44 76 74 37 URL: www.iislweb.com OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS URL: www.iafastro.com E-mail: [email protected] URL : http://cosparhq.cnes.fr Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is responsible for promoting international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space and assisting developing countries in using space science and technology. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs P. O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-4950 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5830 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.unoosa.org United Nations publication Printed in Austria USD 15 Sales No. E.11.I.3 ISBN 978-92-1-101236-1 ST/SPACE/57 *1180239* V.11-80239—January 2011—775 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT VIENNA Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law Progress in space science, technology and applications, international cooperation and space law UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 UniTEd NationS PUblication Sales no. -

View Pdf for Soviet Space Culture

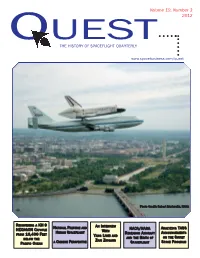

Volume 19, Number 3 2012 OUEST THE HISTORY OF SPACEFLIGHT QUARTERLY www.spacebusiness.com/quest Photo Credit: Robert Markowitz, NASA RECOVERING A KH-99 AN INTERVIEW NATIONAL PRESTIGE AND NACA/NASA ANALYZING TASS HEXAGON CAPSULE WITH HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT RESEARCH AIRCRAFT ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM 16,400 FEET YANG LIWEI AND AND THE BIRTH OF ON THE SOVIET BELOW THE HAI HIGANG A CHINESE PERSPECTIVE Z Z SPACE PROGRAM PACIFIC OCEAN SPACEFLIGHT Contents Volume 19 • Number 3 2012 www.spacebusiness.com/quest 4 An Underwater Ice Station Zebra More Reviews Recovering a KH-99 HEXAGON Capsule from 16,400 Feet Below the Pacific Ocean 64 Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight By David W. Waltrop Edited by Joseph J. Corn 18 National Prestige and Human Spaceflight Review by Dominick A. Pisano A Chinese Perspective 65 Destination Mars: By Liang Yang New Explorations of the Red Planet Book by Rod Pyle 31 China’s Great Leap into Space Review by Bob Craddock An Interview with Yang Liwei and Zhai Zhigang By John Vause 66 Soviet Space Culture Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies 36 NACA/NASA Research Aircraft and the Edited by Maurer, Richers, Rüthers, and Scheide Review by Michael J. Neufeld Birth of Spaceflight By Curtis Peebles 67 The Space Shuttle: Celebrating Thirty Years of NASA’s First Space Plane Managing the News: 44 Book by Piers Bizony Analyzing TASS Announcements on the Review by Roger D. Launius Soviet Space Program (1957-11964) By Bart Hendrickx 68 The Astronaut: Cultural Mythology and Idealised Masculinity Book Reviews Book by Dario Llinares Review by Amy E. -

Master Thesis

Master’s Thesis 2018 30 ECTS Department of International Environment and Development Studies Katharina Glaab Dividing Heaven: Investigating the Influence of the U.S. Ban on Cooperation with China on the Development of Global Outer Space Governance Robert Ronci International Relations LANDSAM The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master’s theses are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master’s programmes ‘International Environmental Studies’, ‘International Development Studies’ and ‘International Relations’. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. © Robert Ronci, May 2018 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies The Faculty of Landscape and Society P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 67 23 00 00 Internet: https://www.nmbu.no/fakultet/landsam/institutt/noragric i ii Declaration I, Robert Jay Ronci, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author: History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology Affd Society August 19, 2014

Project Apollo, Cold War Diplomacy and the American Framing of Global Interdependence by MASSACHUSETTS 5NS E. OF TECHNOLOGY OCT 0 6 201 Teasel Muir-Harmony LIBRARIES Bachelor of Arts St. John's College, 2004 Master of Arts University of Notre Dame, 2009 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology, and Society In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2014 D 2014 Teasel Muir-Harmony. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology affd Society August 19, 2014 Certified by: Signature redacted David A. Mindell Frances and David Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Committee Chair redacted Certified by: Signature David Kaiser C01?shausen Professor of the History of Science Director, Program in Science, Technology, and Society Senior Lecturer, Department of Physics Committee Member Signature redacted Certified by: Rosalind Williams Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Technology Committee Member Accepted by: Signature redacted Heather Paxson William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor, Anthropology Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Signature -

Only Six Chinese Human Spaceflight Missions

Fact Sheet Updated April 29, 2021 CHINA’S HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT PROGRAM: BACKGROUND AND LIST OF CREWED AND AUTOMATED LAUNCHES China's human spaceflight program, Project 921, officially began in 1992. The program is proceeding at a measured pace. The most recent crewed launch, Shenzhou-11 in October 2016, was the 11th flight in the series, but only the sixth to carry a crew. Shenzhou Spacecraft: Shenzhou 1-4 were automated tests of the spacecraft. Shenzhou-8 was an automated test of rendezvous and docking procedures with the Tiangong-1 space station. The others (5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11) carried crews of one, two or three people and were launched in 2003, 2005, 2008, 2012, 2013 and 2016 respectively (see list below) Space Stations: Tiangong-1, China's first space station, was launched in September 2011. It hosted the automated Shenzhou-8 in 2011 and two three-person crews: Shenzhou-9 in 2012 and Shenzhou-10 in 2013. It made an uncontrolled reentry at 8:16 pm April 1, 2018 EDT (00:16 April 2 UTC; 8:16 am April 2 Beijing Time) over the southern Pacific Ocean. Tiangong-1 was a small 8.5 metric ton (MT) module. As first space stations go, it was rather modest -- just less than half the mass of the world's first space station, the Soviet Union’s Salyut 1. Launched in 1971, Salyut 1 had a mass of about 18.6 MT. The first U.S. space station, Skylab, launched in 1973, had a mass of about 77 MT. Today's International Space Station (ISS), a partnership among the United States, Russia, Japan, Europe, and Canada, has a mass of about 400 MT and has been permanently occupied by 2-6 person crews rotating on 4-6 month missions since November 2000.