Ph.D. Afhandling 2016 Jacobsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory

History in the Making Volume 13 Article 5 January 2020 The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory Consuelo S. Moreno CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Moreno, Consuelo S. (2020) "The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory," History in the Making: Vol. 13 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol13/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Movement that Sinned Twice: The Cristero War and Mexican Collective Memory By Consuelo S. Moreno Abstract: Many scattered occurrences in Mexico bring to memory the 1926-1929 Cristero War, the contentious armed struggle between the revolutionary government and the Catholic Church. After the conflict ceased, the Cristeros and their legacy did not become part of Mexico’s national identity. This article explores the factors why this war became a distant memory rather than a part of Mexico’s history. Dissipation of Cristero groups and organizations, revolutionary social reforms in the 1930s, and the intricate relationship between the state and Church after 1929 promoted a silence surrounding this historical event. Decades later, a surge in Cristero literature led to the identification of notable Cristero figures in the 1990s and early 2000s. -

What Price Would You Pay for Freedom?

What price would you pay for freedom? Andy Garcia Eva Longoria as Enrique Gorostieta Velarde as Tulita “The age of martyrdom has not passed.” – from “Our First, Most Cherished Liberty” A statement on religious liberty from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops Ruben Blades Peter O’Toole as President Plutarco Elias Calles Ad Hoc Committee for Religious Liberty as Father Christopher “For Greater Glory vividly depicts the difficult circumstances in which Catholics of that time lived – and died for – their faith. It is a top-flight production whose message of the importance of religious freedom has particular resonance for us today. It is my earnest hope that people of faith throughout our country will rally behind For Greater Glory, and in doing so, will highlight the importance of religious freedom in our society.” – Most Rev. José H. Gomez, Archbishop of Los Angeles Eduardo Verástegui Mauricio Kuri as Blessed Anacleto Gonzalez Flores As Blessed José Sánchez del Rio “This deeply moving account of the Cristeros’ fight for the free- dom of religion in Mexico is very much a story for our own times. “Every person of faith should draw courage from the tragically The faith and courage of the Mexican martyrs -- clergy and laity heroic witness of the Cristeros. Their sacrifice reminds us that unless we learn from history, we risk repeating it. Besides being -- makes us proud to be Catholics.” an important movie, it is extremely well done.” – Most Rev. Michael J. Sheridan, Bishop of Colorado Springs, Colorado ForGreaterGlory.com – Fr. Andrew Small, -

Centro De Investigación Y Docencia Económicas, A.C

CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DOCENCIA ECONÓMICAS, A.C. REESCRIBIENDO LA HISTORIA LA GUERRA CRISTERA EN EL CINE MEXICANO ANTES Y DESPUÉS DE LA ALTERNANCIA TESINA QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADA EN CIENCIA POLÍTICA Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES PRESENTA GEORGINA JIMÉNEZ RÍOS DIRECTORA DE TESINA: LIC. TANIA ISLAS WEINSTEIN CIUDAD DE MÉXICO MARZO, 2017 Agradecimientos A mamá y papá, porque su amor por mí siempre fue más grande que cualquier duda que tuvieran acerca de mi camino. Por siempre apoyar y por siempre esperar con los brazos abiertos cuando sentí la necesidad de volver a casa. Por confiar en que caminaría bien y por ayudarme a confiar en que lo haría. A Itzel y a Luisa, por ser confidentes y amigas además de hermanitas, por siempre creer en mí y por recordarme que lo hiciera cuando lo olvidé. A CPRI 2011-2015, por ser una generación tenaz e intensa, con dudas, con sueños y ambiciones. A la Banda Pesada, por haberse convertido en mi segunda familia y por jamás dejarme sentir abandonada en esta monstruosa ciudad. Por los domingos de estudio, las noches de fiesta y las pláticas ñoñas de comedor. Por ser y por ayudarme a descubrir quién soy. A Sergio y a Lalo porque sin su pasión por el cine esta tesina nunca se hubiera escrito. Por servir de inspiración, por compartirme de su curiosidad y por ayudarme a satisfacerla. Por compartirme también de su amor y fascinación por el arte y el conocimiento. A Mariel, por las pláticas eternas y el apoyo incondicional. Por el profundo cariño y las preguntas incontestables sobre el mundo y la humanidad. -

Adolescent Pedagogy As Seen Through the Theological Lens of Latino Spirituality

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Th.D. Dissertations Scholarship 5-2020 Entregado a los Estudiantes: Adolescent Pedagogy As Seen Through the Theological Lens of Latino Spirituality Christian Arellano La Salle University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/religion_thd Recommended Citation Arellano, Christian, "Entregado a los Estudiantes: Adolescent Pedagogy As Seen Through the Theological Lens of Latino Spirituality" (2020). Th.D. Dissertations. 12. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/religion_thd/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Th.D. Dissertations by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. La Salle University School of Arts and Sciences Graduate Program in Theology and Ministry Dissertation Entregado a los Estudiantes: Adolescent Pedagogy as seen through the Theological Lens of Latino Spirituality By Christian Arellano (B.A., La Salle University, 2003, Religion/ Secondary Education M.A, Saint Charles Borromeo Seminary, Theology) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology 2020 WE, THE UNDERSIGNED MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE, HAVE APPROVED THIS THESIS Entregado a los Estudiantes: Adolescent Pedagogy as seen through the Theological Lens of Latino Spirituality By Christian Arellano COMMITTEE MEMBERS _____Bro. John Crawford, F.S.C. – signed electronically _________________________________________________________________________ Bro. John Crawford, F.S.C., Ph.D. (Mentor) La Salle University ____Fr.. Kenneth Hallahan, Ph.D. – signed electronically __________________________________________________________________________ Fr. Kenneth Hallahan, Ph.D. (1st Reader) La Salle University _______Fr. -

Mexican Migrants and the 1920S Cristeros Era: an Interview with Historian Julia G

Diálogo Volume 16 Number 2 Article 15 2013 Mexican Migrants and the 1920s Cristeros Era: An Interview with Historian Julia G. Young Peter J. Casarella DePaul University Julia G. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Casarella, Peter J. and Young, Julia G. (2013) "Mexican Migrants and the 1920s Cristeros Era: An Interview with Historian Julia G. Young," Diálogo: Vol. 16 : No. 2 , Article 15. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol16/iss2/15 This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mexican Migrants and the 1920s Cristeros Era: An Interview with Historian Julia G. Young Peter J. Casarella DePaul University during the Cristero Revolt of 1926-1929. In this interview, Editor’s Note: The release last year of the film For Greater she also addresses ideas of presumed secularization after Glory,1 provided an opportunity to learn about an early 20th immigration. century segment of Mexican contemporary history, of which many people in the U.S. were unaware. While the Cristeros (“Christers”) Revolt was, in many ways, a final segment Peter J. Casarella (PJC): It’s an honor to speak to you, Julia. to the Mexican Revolution launched in 1910, a struggle As a professional historian in [the] areas of the Mexican which sought rights and citizenship for all (which had not Revolution and Cristero Revolt, you can provide interesting been achieved through independence from Spain a century perspective on this film. -

Juan Rulfo: Un Ojo Fotográfico Puesto En La Creación Literaria

Juan Rulfo: Un ojo fotográfico puesto en la creación literaria Rosy Maribel Salgado García Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Humanidades Maestría en Estudios Literarios Bogotá, Colombia 2016 Juan Rulfo: Un ojo fotográfico puesto en la creación literaria Rosy Maribel Salgado García Tesis presentada como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Magíster en Estudios Literarios Director (a): Fabio Jurado Valencia Línea de Investigación: Literatura comparada Universidad Nacional de Colombia Facultad de Humanidades Maestría en Estudios Literarios Bogotá, Colombia 2016 “El hombre camina días enteros entre los árboles y las piedras. Raramente, el ojo se detiene en una cosa, y cuando la ha reconocido como el signo de otra: una huella en la arena indica el paso del tigre, un pantano anuncia una vena de agua, la flor del hibisco el fin del invierno. Todo el resto es mudo, es intercambiable; árboles y piedras son solamente lo que son.” Ítalo Calvino: Las Ciudades Invisibles (1972). “Un fotógrafo es, literalmente, Alguien que dibuja con la luz Alguien que escribe y reescribe el mundo con luces y sombras”. La sal de la tierra, Sebastião Salgado A la memoria del profesor Carlos Pacheco. Agradecimientos Agradezco a mi abuela Ana María Parra por su eterno cariño; ella me oirá allá ―en donde el aire cambia el color de las cosas‖. A mis padres José Vicente Salgado Sánchez y Luz Marlene García Parra por su apoyo y paciencia y a mis hermanas Ana María, Jazmín y Nazly Salgado por su compañía en mi caminar. Igualmente a mis demás familiares y amigos. A Óscar Moreno González por su motivación, su comprensión e inefable amor. -

(Pdf) Download

St. JOHNCATHOLIC PAUL PARISH II 956956 S.S. 10th10th Ave.,Ave., Kankakee, Kankakee, IllinoisIllinois 60901 815815-933-7683-933-7683 WELCOME to the family BIENVENIDO a la familia THE TRANSFIGURATION OF THE LORD AUGUST 6, 2017 Pastor: Fr. Santos “Sunny” Castillo Parochial Vicar: Fr. Fredy Santos, CSV Deacons: David Marlowe & Greg Clodi WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE St. John Paul II West St. Martin of Tours Church 953 S. 9th Ave., Kankakee Saturday 4:30 pm Vigil Mass 6:00 pm Misa en Español de Vigilia Sunday 9:30 am 11:30 am 5:00 pm St. John Paul II Central St. Rose of Lima Church 486 W. Merchant St., Kankakee Sunday 8:00 am St. John Paul II East St. Teresa Church 307 N. St. Joseph Ave., Kankakee Sunday 12:00 pm Misa en Español DAILY MASS SCHEDULE St. John Paul II West St. Martin of Tours Church Monday thru Friday 7:30 am Tuesday 6:00 pm Misa en Enpañol “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” - 1 - MUSINGS ON A MEXICO PILGRIMAGE RECUERDOS SOBRE LA PEREGRINACIÓN A MEXICO Many of you know that I went on a short pilgrimage to the Muchos de ustedes saben que fui en pequeña peregrina- Shrine of Guadalupe last month, and visited some amazing ción al santuario de Guadalupe el mes pasado, y visité towns around the Federal District of Mexico City. This was my algunos pueblos hermosos alrededor del Distrito Federal. fourth trip to Mexico and my third visit to Mexico City. My first Este era mi cuarto viaje a México y mi tercer visita a la trip ever was an eight-week Spanish language program, where Ciudad de México. -

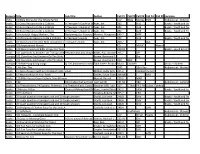

Resource Typetitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 Call #4 Call

ResourceTitle Type Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 Call #4 Call #5 Location DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Stories DVD Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649.7 MEE Books 10 More Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide Auer, Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Ways to Get Into the New Testament, A Teenager's Guide Auer, Jim 220.7 AUE Compact 100Discs Inspirational Hymns CD MUSIC Hymns Books 100 Most Important Bible Verses For Teens 220.52 Books - youth & teen Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome. 265.7 KEL Compact 101Discs Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Bro Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact 120Discs Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters ProductionsMusic Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD 13th Day Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann. 235.2 Elizabeth Seton Books 15 Ways to Nourish Your Faith Davies, Susan Shannon248.482 DAV Books 150 Bible Verses Every Catholic Should Know Madrid, Patrick 220.6 MAD DVDs 180 33 minutes that will rock your world! 241.69 180 Audiovisual - General Books 1st Thessalonians, Philippians, Philemon, 2nd Thessalonians, Colossians,Havener Ephesians OSB, Ivan 227 1 Thes, 2Phil, Thes PhilemonColoss, Ephesia Books 2 Minutes A Day Choices Making Good OnesStore, Family Christian242.2 FAM Books - Youth and Teen Books 20 Holy Hours Crawley-Boevey, Mateo265.2 CRA Books 20 tough questions teenagers ask and 20 tough answers Davitz, Lois Jean. -

Estado VS Clero

CONTENIDOS 13 AL 19 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 BOLETÍN #237 TEMA DE LA SEMANA: Estado VS Clero ............................................................................................................................ 4 1. Aumenta la confrontación Estado-clero .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. La Iglesia es insustituible para reconstruir México, asegura Cardenal ................................................................................ 4 3. El premio que le negaron a Mancera ................................................................................................................................... 6 4. “Se sirven con cuchara grande”, critica Iglesia a Gobierno, SCJN y Congreso por subirse el sueldo .................................. 8 5. Obsceno aumento salarial de funcionarios en México: Iglesia Católica .............................................................................. 9 6. Critican aumento de sueldo a servidores ........................................................................................................................... 10 7. Iglesia católica se lanza vs. aumento a salario de funcionarios ......................................................................................... 10 IGLESIAS Y VIOLENCIA EN MÉXICO ................................................................................................................................. 11 8. Iglesia condena complicidad entre autoridades y crimen ................................................................................................ -

C:\Users\John7\Documents\Greeting Cards\Pamphlets Biblical Handouts

‘Freedom is Our Lives’ . Flores — who is sometimes referred to as the “Mexican Gandhi”— favored civil involves the execution of St. José María The new movie, For Greater Glory: The Robles Hurtado, a martyred priest and True Story of Cristiada unveils a time when disobedience. Others, like Father José Reyes Vega and Victoriano Ramírez, known as “El Knight of Columbus who blessed and Mexican Christians, in the pursuit of forgave his killers in the face of death. religious freedom, had to choose between Catorce,”resorted to armed resistance, beginning a grassroots rebellion of Mexican Although the film is about specific their faith and their lives. It was directed by historical events, the filmmakers believe the Titanic and Lord of the Rings special Catholics from which the term “Cristiada” originated. that its message about religious freedom effects genius, Dean Wright. Therefore it is universal. contains gripping and spectacular action The history of the Cristero War remains with breathtaking scenery. But it is the largely unknown, even to Mexicans. Eduardo “Welive in a time where religious story of heroic martyrdom that will draw Verástegui, who portrays González Flores in freedom is as tenuous as it’sever been,” crowds to theaters. The talented cast said Wright. includes Andy Garcia, Peter O’Toole and The Untold Story of the Knights during Eva Longoria. the Cristiada The Cristero War is a conflict that lasted from 1926 to 1929. This often forgotten era On an ordinary January day in 1927, as of Mexican history is captured in [this] film Yocundo Durán walked home in comprised of an ensemble of talented and Chihuahua, Mexico, he crossed paths award-winning actors. -

5-18-12 NTC Jeff's.Indd

Newsmagazine Bringing the Good News to the Diocese of Fort Worth Vol. 28 No. 6 June 2012 Nolan students come to aid of classmate's family and their neighborhood in Tornado cleanup By Joan Kurkowski-Gillen Correspondent itch Titsworth expected the worst as he approached the South Arlington neighborhood hit by an EF-2 tornado AprilM 3. The Nolan Catholic High School senior knows the devastation a violent twister can leave behind. While visiting his grandparents living in Joplin, Missouri, last July, he noticed crews still picking up debris from the May 22, 2011 monster tornado that rolled through their hometown. “I was happy there wasn’t more damage,” said Titsworth, one of 30 students who spent Good Friday pulling up tree Thirty Nolan Catholic High School students spent much of Good Friday helping out Arlington residents whose homes were damaged in the flurry of tornados that touched down in the area April 3. stumps and hauling off fence panels from After helping with a Nolan student's home, they assisted with others in the neighborhood (Photos courtesy of Nolan Catholic High School) homes hit by the funnel cloud. “And I’m glad no one was hurt.” Majestic oak trees that lined the in their blue t-shirts with shovels, rakes, and was spared damage. “It was a good feeling to Nolan students huddled in school neighborhood were split in half and saws was an incredible sight,” Karen Crimmins help people and be part of the experience.” hallways as warning sirens blared in East fencing was blown apart. Several homes said emotionally. -

Emiliano Zapata

Access to History for the IB Diploma The Mexican Revolution 1910–40 Philip Benson Yvonne Berliner 9781444182347.indb 1 19/12/13 11:22 AM This page intentionally left blank Access to History for the IB Diploma The Mexican Revolution 1910–40 9781444182347.indb 3 19/12/13 11:22 AM The material in this title has been developed independently of the International Baccalaureate®, which in no way endorses it. The Publishers would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce copyright material: Photo credits p.16 © Bettmann/Corbis; p.44 © PRISMA ARCHIVO/Alamy; p.49 © Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy; p.57 © Everett Collection Historical/Alamy; p.86 © Bettmann/Corbis; p.122 © Bettmann/Corbis; p.180 © The Granger Collection, NYC/TopFoto © 2013 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./DACS; p.197 © Diego Rivera painting the East Wall of ‘Detroit Industry’ (b/w photo)/Detroit Institute of Arts, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library © 2013 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./DACS; p.198 © The Granger Collection, NYC/TopFoto © DACS 2013; p.204 © Archivo Gráfico de El Nacional /INEHRM. Acknowledgements P.27 Donald B. Keesing, ‘Structural Change Early in Development: Mexico’s Changing Industrial and Occupational Structure from 1895 to 1950’, The Journal of Economic History, Volume 29(4) (1969). Reproduced by permission of Cambridge University Press; p.122 Héctor Aguilar Camin and Lorenzo Meyer, ‘Oil production between 1934 and 1940 (thousands of barrels)’, In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution: Contemporary Mexican History, 1910–1989, translated by Luis Alberto Fierro (University of Texas Press), copyright © 1993.