North of 26° South and the Security of Australia Views from the Strategist Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives

2021 WAIRC 00144 WA HEALTH SYSTEM - AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION - REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES - INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION PARTIES NORTH METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE, CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH SERVICE, EAST METROPOLITAN HEALTH SERVICE & OTHERS APPLICANTS -v- AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION, INDUSTRIAL UNION OF WORKERS PERTH RESPONDENT CORAM COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL DATE MONDAY, 24 MAY 2021 FILE NO/S AG 8 OF 2021 CITATION NO. 2021 WAIRC 00144 Result Agreement registered Representation Applicants Mr L Martyr (as agent) Respondent Mr M Olson (as agent) Order HAVING heard from Mr L Martyr (as agent) on behalf of the applicants and Mr M Olson (as agent) on behalf of the respondent, the Commission, pursuant to the powers conferred under the Industrial Relations Act 1979 (WA), orders – THAT the agreement made between the parties filed in the Commission on 6 May 2021 entitled WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020 attached hereto be registered as an industrial agreement in replacement of the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses - Industrial Agreement 2018 which by operation of s 41(8) is hereby cancelled. COMMISSIONER T EMMANUEL WA HEALTH SYSTEM – AUSTRALIAN NURSING FEDERATION – REGISTERED NURSES, MIDWIVES, ENROLLED (MENTAL HEALTH) AND ENROLLED (MOTHERCRAFT) NURSES – INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT 2020 INDUSTRIAL AGREEMENT NO: AG 8 OF 2021 PART 1 – APPLICATION & OPERATION OF AGREEMENT 1. TITLE This Agreement will be known as the WA Health System – Australian Nursing Federation – Registered Nurses, Midwives, Enrolled (Mental Health) and Enrolled (Mothercraft) Nurses – Industrial Agreement 2020. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

Mr Luke Gosling (PDF 110KB)

Submission No 59 Inquiry into Australia’s Relationship with Timor-Leste Name: Mr Luke Gosling Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee Inquiry into Australia's relationship with Timor-Leste Luke Gosling, Darwin NT 1. Bilateral relations at the parliamentary and government levels; Our deep relationship with Timor-Leste goes back to the Second World War where a group of Australian Commandos with the help of the Timor-Leste people operated from late 1941 until late 1942. The Timorese people suffered greatly, with at least as many civilian casualties as our Forces suffered in the entire War. For a small population that loss was huge. The Commandos and their Timor-Leste colleagues conducted a classic guerilla Warfare campaign against the Japanese Imperial Forces and a unique bond was formed that was covered in a film I co-produced, screened on Channel 9, called ”A Debt of Honor”. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofAK6roD4dY&feature=youtu.be&noredirect=1) The title came from a comment by General Peter Cosgrove, Commander of the Australian-led International Force for East Timor (INTERFET), that our intervention was in part repayment of that debt of honor from World War II. Our ongoing relationship with Timor-Leste is an essential one and one that is taken very seriously and taken to heart by people in Darwin, Palmerston and the Top End. The Parliamentary Friends of Timor-Leste group plays an important role in navigating a course for our relationship that connects and strengthens our bonds with our good neighbors and friends in Timor-Leste and the work of ALP International has similarly been providing an important link through capacity building for better governance and more transparent processes in Timor-Leste political parties. -

DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49

DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 Incorporating REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING edited by Glenn Hauser, http://www.worldofradio.com Items from DXLD may be reproduced and re-reproduced only if full credit be maintained at all stages and we be provided exchange copies. DXLD may not be reposted in its entirety without permission. Materials taken from Arctic or originating from Olle Alm and not having a commercial copyright are exempt from all restrictions of noncommercial, noncopyrighted reusage except for full credits For restrixions and searchable 2018 contents archive see http://www.worldofradio.com/dxldmid.html [also linx to previous years] NOTE: If you are a regular reader of DXLD, and a source of DX news but have not been sending it directly to us, please consider yourself obligated to do so. Thanks, Glenn WORLD OF RADIO 1957 contents: Australia, Brasil, China, Cuba, France and non, Japan/Korea North non, Nigeria and non, Saudi Arabia, Somaliland, Spain, Sudan, Tajikistan/Tibet non, USA, unidentified; contests; what is DX? and the propagation outlook dxld1847_plain 1 / 115 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - WORLD OF RADIO PODCASTS: 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49 SHORTWAVE AIRINGS of WORLD OF RADIO 1957, November 20-26 2018 Tue 0030 WRMI 7730 [confirmed] Tue 0200 WRMI 9955 [confirmed] Tue 2030 WRMI 7780 [confirmed] Wed 1030 WRMI 5950 [zzz] Wed 2200 WRMI 9955 [confirmed] -

List of Boundary Lines

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com List of Boundary Lines The line which demarcates the two countries is termed as Boundary Line List of important boundary lines Durand Line is the line demarcating the boundaries of Pakistan and Afghanistan. It was drawn up in 1896 by Sir Mortimer Durand. Hindenburg Line is the boundary dividing Germany and Poland. The Germans retreated to this line in 1917 during World War I Mason-Dixon Line is a line of demarcation between four states in the United State. Marginal Line was the 320-km line of fortification on the Russia-Finland border. Drawn up by General Mannerheim. Macmahon Line was drawn up by Sir Henry MacMahon, demarcating the frontier of India and China. China did not recognize the MacMahon line and crossed it in 1962. Medicine Line is the border between Canada and the United States. Radcliffe Line was drawn up by Sir Cyril Radcliffe, demarcating the boundary between India and Pakistan. Siegfried Line is the line of fortification drawn up by Germany on its border with France.Order-Neisse Line is the border between Poland and Germany, running along the Order and Neisse rivers, adopted at the Poland Conference (Aug 1945) after World War II. 17th Parallel defined the boundary between North Vietnam and South Vietnam before two were united. 24th Parallel is the line which Pakistan claims for demarcation between India and Pakistan. This, however, is not recognized by India 26th Parallel south is a circle of latitude which crosses through Africa, Australia and South America. 30th Parallel north is a line of latitude that stands one-third of the way between the equator and the North Pole. -

Annual Report Annual | 2016–17 Report

DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF HOUSE THE OF DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Annual Report Annual Report | Annual 2016–17 2016–17 DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Annual Report 2016–17 © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 ISSN 0157-3233 (Print) ISSN 2201-1730 (Online) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia Licence. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au. Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the website of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet at www.dpmc.gov.au/pmc/publication/commonwealth-coat-arms-information-and-guidelines. Produced by the Department of the House of Representatives Editing and indexing by Wilton Hanford Hanover Design by Lisa McDonald Printing by CanPrint Communications Unless otherwise acknowledged, all photographs in this report were taken by staff of the Department of the House of Representatives. Front cover image: House of Representatives Chamber. Photo: Getty Images. Back cover image: Roof detail inside the House of Representatives Chamber. Photo: Penny Bradfield, Auspic/DPS. The department welcomes your comments on this report. To make a comment, or to request more information, please contact: Serjeant-at-Arms Department of the House of Representatives Canberra ACT 2600 Telephone: +61 2 6277 4444 Facsimile: +61 2 6277 2006 Email: [email protected] Website: www.aph.gov.au/house/dept Web address for report: www.aph.gov.au/house/ar16-17 ii Department of the House of Representatives To be supplied Annual Report 2016–17 iii About this report The Department of the House of Representatives provides services that allow the House to fulfil its role as a representative and legislative body of the Australian Parliament. -

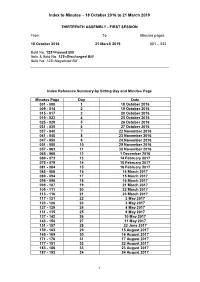

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 21 March 2019 001 – 523 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 - 008 1 18 October 2016 009 - 014 2 19 October 2016 015 - 017 3 20 October 2016 019 - 023 4 25 October 2016 025 - 029 5 26 October 2016 031 - 035 6 27 October 2016 037 - 040 7 22 November 2016 041 - 045 8 23 November 2016 047 - 050 9 24 November 2016 051 - 055 10 29 November 2016 057 - 063 11 30 November 2016 065 - 068 12 1 December 2016 069 - 073 13 14 February 2017 075 - 079 14 15 February 2017 081 - 084 15 16 February 2017 085 - 088 16 14 March 2017 089 - 094 17 15 March 2017 095 - 098 18 16 March 2017 099 - 107 19 21 March 2017 109 - 111 20 22 March 2017 113 - 116 21 23 March 2017 117 - 121 22 2 May 2017 123 - 126 23 3 May 2017 127 - 129 24 4 May 2017 131 - 135 25 9 May 2017 137 - 142 26 10 May 2017 143 - 150 27 11 May 2017 151 - 157 28 22 June 2017 159 - 163 29 15 August 2017 165 - 169 30 16 August 2017 171 - 176 31 17 August 2017 177 - 181 32 22 August 2017 183 - 186 33 23 August 2017 187 - 192 34 24 August 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 193 - 196 35 10 October 2017 197 - 199 36 11 October 2017 201 - 203 37 12 October 2017 205 - 208 38 17 October 2017 209 - 213 39 18 October 2017 215 - 220 40 19 October 2017 221 - 225 41 21 November 2017 227 - 233 42 22 November 2017 235 - 247 43 23 -

214 Pastoral Settlement of Far South-West

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace 214 PASTORAL SETTLEMENT OF FAR SOUTH-WEST QUEENSLAND (1866-1900) [By K. T. CAMERON, Hon. Secretary of the Society] This stretch of country, lying just west of the great mulga belt known as the "Channel Country," extends from the Grey Range to the South Australian and Northern Territory borders, and is traversed by the numerous channels of the Diamantina and Georgina Rivers, and those even more numerous of Cooper's Creek. In spite of its low rainfah this is one of the best fattening and wool growing areas in the State. In 1866 Alexander Munro occupied Nockatunga, and in the sam.e year L. D. Gordon Conbar. The fohow ing year saw the arrival of the Costehos and Patrick Durack. The latter became the original lessee of Thy- lungra on Kyabra Creek. The Costehos securing Mobhe on Mobile Creek and Kyabba (now known as Kyabra), John Costeho, pushing further west in 1875 secured Monkira, P. and J. Durack in 1873 having secured Galway Downs. In 1880 some enterprising carriers travelling out with waggons loaded with stores from the rail head of the railway line being built westward from Rock hampton, formed a depot at Stoney Point. Soon after a permanent store was erected on the site; thus grew the township of Windorah. The Lindsays and Howes from the South Austra lian side in 1876 were responsible for the forming of Arrabury. In the extreme western area in the 1870s James Wentworth Keyes settled Roseberth and Chesterfield on the Diamantina. -

List of International Boundary Lines | GK Notes in PDF

List of International Boundary Lines | GK Notes in PDF Radcliffe Line Radcliffe Line was drawn by Sir Radcliffe. It marked the boundary between India and Pakistan. The Radcliffe Line was officially announced on August 17, 1947, a few days after the independence of India and Pakistan. The newly demarcated borders resulted into one of the biggest human migrations in modern history, with roughly 14 million people displaced. More than one million people were killed. The Maginot Line The Maginot Line named after the French Minister of War André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles, and weapon installations built by France in the 1930s to deter invasion by Germany. The Mannerheim Line The Mannerheim Line was a defensive fortification line on the Karelian Isthmus built by Finland against the Soviet Union. The line was constructed in two phases: 1920–1924 and 1932–1939. By November 1939, when the Winter War began, the line was by no means complete The Medicine Line The medicine line, a hundred-mile stretch of the U.S. Canadian border at the top of Blaine County, Montana, epitomizes borderlessness . Natives called the border between Canada and the United States the Medicine Line, because during the 19th century Indian wars American troops respected it as if by magic. A century later, the medicine line deserves our respect for many different reasons: the history of peaceful coexistence it represents, and the model it offers for the future. The Hindenburg Line The Hindenburg Line is the boundary dividing Germany and Poland. The Hindenburg Line was a German defensive position of World War I, built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front, from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. -

12 September 1945

[COUNCIL)] of the movement and spreads the interest ?IgtigiBfb2 over a renter number of people. I hope Qmirnmc. that. the existing broadly-based interests W~ednesday, 12th September, 1945. will continue in the future. There are so many aspects of national fitness work that PAGE it is necessary that all bodies operating in Motion: North-West, a%to action to reftore economy 60$ the country districts particularly should co- Blls: Mine Workers' lellet(%Wax Senice) Act Amend- mentlt.1. 023 operate for the welfare of the movement. Ri~ In vate an 'riion Act Amendment, One aspect that many of the country corn- Act Amendment IR.........62 Police Act Amendment1 Act, 1902, Amendment. nittecs were particularly interested in is the is..........................623 ,question of sales tax being charged on equipment purchased by them, even though the funds were being expended through the central body. I understand that at first it The PRESIDENT took the Chair at 4.31) was anticipated that if the funds were ex- pan., and read prayers. pended through the central body, the Com- monwealth Government would be able to MOTION-NORTH-WEST. waive the collection of sales tax. However, As to Action to Restore Economy. that was found impossible with the result that, apparently, local committees, but for HON. r. 9. WELSH (North) [4.35]: 1 the introduction of the Bill now before the move- House, would have been faced with the That, in view of tie serious position exist- necessity t9~ pay sales tax on all equipment lug in the northern part of the State, this House considers that tim Government should installed in the various centres. -

GK Digest for SSC CGL V2 455: Accession of Skandagupta

Index- GK Digest for SSC CGL319–320 v2: Commencement of Gupta era. Subject - History - Page No : 1-19 380: Accession of Chandragupta II Subject - Geography - Page No : 19-28 ‘Vikramaditya’ Subject - General Science - Page No : 28-78 405–411: Visit of Chinese traveller Fahien. 415: Accession of Kumargupta I. GK Digest for SSC CGL v2 455: Accession of Skandagupta. 606–647: Harshavardhan’s reign. SUBJECT - HISTORY II. MEDIEVAL PERIOD Indian History – Important Dates BC ( BEFORE CRIST ) 712: First invasion in Sindh by Arabs (Mohd. 2300–1750 : Indus Valley Civilization. Bin Qasim). From 1500 : Coming of the Aryans. 836: Accession of King Bhoja of Kannauj. 1200–800 : Expansion of the Aryans in the 985: Accession of Rajaraja, the Chola ruler. Ganga Valley. 998: Accession of SultanMahmud Ghazni. 600 :Age of the 16 Mahajanapadas of 1001: First invasion of India by Mahmud northern India. Ghazni who defeated Jaipal, ruler of Punjab. 563–483: Buddha’s Life-span. BankExamsToday.com 1025: Destruction of Somnath Temple by 540–468: Mahavir’s Life-span. Mahmud Ghazni. 362–321: Nanda dynasty. 1191: First battle of Tarain. 327–326 : Alexander’s invasion of India. It 1192: Second battle of Tarain. opened a land route between India and 1206 :Accession of Qutubuddin Aibak to the Europe. throne of Delhi. 322: Accession of Chandragupta Maurya. 1210 :Death of Qutubuddin Aibak. 305: Defeat of Seleucus at the hands of 1221: Chengiz Khan invaded India (Mongol Chandragupta Maurya. invasion). 273–232: Ashoka’s reign. 1236: Accession of Razia Sultana to the 261: Conquest of Kalinga. throne of Delhi. 145–101: Regin of Elara, the Chola king of 1240: Death of Razia Sultana. -

ALP Federal Caucus by Factional Alignment February 2021 National NSW VIC QLD SA WA TAS NT ACT

ALP federal caucus by factional alignment February 2021 National NSW VIC QLD SA WA TAS NT ACT House of Reps Right Chris Bowen Richard Marles Jim Chalmers Nick Champion Matt Keogh Luke Gosling David Smith Tony Burke Bill Shorten Shayne Neumann Steve Georganas Madeleine King Jason Clare Mark Dreyfus Milton Dick Amanda Rishworth Joel Fitzgibbon Peter Khalil Anika Wells Ed Husic Anthony Byrne Michelle Rowland Rob Mitchell Sharon Bird Clare O'Neil Justine Elliot Josh Burns Mike Freelander Daniel Mulino Chris Hayes Joanne Ryan Kristy McBain Tim Watts Emma McBride Meryl Swanson Matt Thistlethwaite House of Reps Independent Andrew Leigh Alicia Payne House of Reps Left Anthony Albanese Andrew Giles Terri Butler Mark Butler Josh Wilson Julie Collins Warren Snowdon Pat Conroy Julian Hill Graham Perrett Tony Zappia Anne Aly Brian Mitchell Tanya Plibersek Catherine King Pat Gorman Stephen Jones Libby Coker Susan Templeman Ged Kearney Linda Burney Peta Murphy Anne Stanley Brendan O'Connor Julie Owens Lisa Chesters Fiona Phillips Maria Vamvakinou Sharon Claydon Kate Thwaites Senate Right Kristina Keneally Raffaele Ciccone Anthony ChisholmDon Farrell Pat Dodson Catryna Bilyk Tony Sheldon Kimberley Kitching Alex Gallacher Glenn Sterle Helen Polley Deb O'Neill Marielle Smith Senate Left faction Tim Ayres Kim Carr Murray Watt Penny Wong Sue Lines Carol Brown Malarndirri McCarthy Katy Gallagher Jenny McAllister Jess Walsh Nita Green Louise Pratt Anne Urquhart Total House Reps Right 14 11 4 3 2 0 1 1 36 Total House Reps Left 10 10 2 3 2 2 1 0 30 Total House Reps Indi 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 SuB-total 24 21 6 6 4 2 2 3 68 Total Senate Right 3 2 1 3 2 2 0 0 13 Total Senate Left 2 2 2 1 2 2 1 1 13 SuB-total 5 4 3 4 4 4 1 1 26 ALP Caucus Indi total 2 Left total 43 Right total 49 Total 94.