I N D I a I N 1 5 0 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepping out of the Frame Alternative Realities in Rushdie’S the Ground Beneath Her Feet

Universiteit Gent 2007 Stepping Out of the Frame Alternative Realities in Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het verkrijgen van de graad van Prof. Gert Buelens Licentiaat in de taal- en letterkunde: Prof. Stef Craps Germaanse talen door Elke Behiels 1 Preface.................................................................................................................. 3 2 Historical Background: the (De-)Colonization Process in India.......................... 6 2.1 The Rise of the Mughal Empire................................................................... 6 2.2 Infiltration and Colonisation of India: the Raj ............................................. 8 2.3 India, the Nation-in-the-making and Independence (1947) ....................... 11 2.3.1 The Rise of Nationalism in India ....................................................... 11 2.3.2 Partition and Independence................................................................ 12 2.3.3 The Early Postcolonial Years: Nehru and Indira Gandhi................... 13 2.4 Contemporary India: Remnants of the British Presence............................ 15 3 Postcolonial Discourse: A (De)Construction of ‘the Other’.............................. 19 3.1 Imperialism – Colonialism – Post-colonialism – Globalization ................ 19 3.2 Defining the West and Orientalism............................................................ 23 3.3 Subaltern Studies: the Need for a New Perspective.................................. -

Ralph Fitch, England's Pioneer to India and Burma

tn^ W> a-. RALPH FITCH QUEEN ELIZABETH AND HER COUNSELLORS RALPH FITCH flMoneet; to Snfcta anD 3Burma HIS COMPANIONS AND CONTEMPORARIES WITH HIS REMARKABLE NARRATIVE TOLD IN HIS OWN WORDS + -i- BY J. HORTON RYLEY Member of the Hnkhiyt Society LONDON T. FISHER UNWIN PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1899 reserved.'} PREFACE much has been written of recent years of the SOhistory of what is generally known as the East India Company, and so much interesting matter has of late been brought to light from its earliest records, that it seems strange that the first successful English expedition to discover the Indian trade should have been, comparatively speaking, overlooked. Before the first East India Company was formed the Levant Com- pany lived and flourished, largely through the efforts of two London citizens. Sir Edward Osborne, sometime Lord Mayor, and Master Richard Staper, merchant. To these men and their colleagues we owe the incep- tion of our great Eastern enterprise. To the fact that among them there were those who were daring enough, and intelligent enough, to carry their extra- ordinary programme into effect we owe our appear- ance as competitors in the Indian seas almost simultaneously with the Dutch. The beginning of our trade with the East Indies is generally dated from the first voyage of James Lancaster, who sailed from Plymouth in 1591. But, great as his achievement was, , **** 513241 vi PREFACE and immediately pregnant with consequences of a permanent character, he was not the first Englishman to reach India, nor even the first to return with a valuable store of commercial information. -

Lusophone Africa-Rule of Law Political

INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE DE JURISTES - COMISION INTERNACIONAL DE JUR.'STAS INTERNATIONALE JURISTEN-KOMMISSION 6, RUE DU MONT-DE-SION, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND - TELEPHONE 25 53 00 CABLE ADDRESS-. INTERJURISTS PORTUGUESE AFRICA AND THE RULE OF LAW A STUDY OP THE POLITICAL, ECONOMIC and SOCIAL SITUATION OF THE AFRICAN POPULATIONS IN THE PORTUGUESE TERRITORIES OP CONTINENTAL APRICA Ph.COMTE June 15f 1962 TABLE OP CONTENTS PRELIMINARY NOTE MAPS OP ANGOLA AND MOZAMBIQUE INTRODUCTION Chapter I. INTEGRATION*, THE THEORY AND ITS LIMITS Part I. The Political Unity of the Portuguese Nation §1. Political. Unity against the .Historical Background of Portuguese Colonial Policy §2. Political Unity under Current Positive Law I. The Principle of Political Unity II. Administrative Diversity * Part II. Assimilation of the Natives in Law :§1, Assimilation in the History of Portuguese Colonial Policy ; §2. The Status of the Natives Under the 1933 Constitution I, The Constitution of 1933 II* The Organic Law Relating to Portuguese Overseas Territories (Act'n°2066 of June.27, 1953) III. The Statute of Indigenous Persons of Portuguese Nationality in the Provinces of Portuguese Guinea, Angola.and Mozam bique (Legislative Decree n$S‘*666 of May 20, 1954) §3» Legislative Decree n°43.893 of September 6, 1961 Chapter II. THE POLITCAL ^ND ADMINISTRATIVE INSTITUTIONS Part I. The Political Rights of the Native Part II. The Administrative System §1. The Organs of Central•’ Pt^wer I. The Constitutional Organs of the Portuguese Republic II,- The Administration of the Overseas Provinces §2, The Organs .of Administration.in the .Overseas Provinces ; §3, The Administration of the African'Rural Areas Part III, The Judicial System I, The System Prior to September 6, 1961s Duality of Jurisdiction II. -

The Age of Exploration

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OE ART THE AGE OF EXPLORATION Pictures of explorers wko sought new routes for Eastern trade is found the 'Sf.i- World on the uay, of rulers who urged them on, of phies they visited & of the treasures they found in the East NEW YORK 1942 THE U.E OF EXPLORATION The exploration of the world has not been confined to any one period, but has been rather a continuous process of discovering and forgetting, of forming relationships and breaking them—relation- of conquest, of trade, of culture. Today, however, the period of expansion east and west, from the fifteenth through the iteenth century, it generally called the "Age of Exploration." This expansion grew out of the need of the countries of northern and urope to find .1 direct way of trading with the E; pices had been borne by caravan across the plains of Asia and carried bv ships through the Black or the Red Sea ur the Persian Gulf, finally reaching Mediterranean ports. But after the fall of the Roman empire long-distance commerce gradually c< n the knowl edge of distant lands grew dim; the belief that the world was round, common among educated men of Roman days, was almost forgotten, and geographers frightened mariners with descriptions of abysses at the world 'ilgrimi and crusaders, however, kept alive or r me knowledge of the nearer East, and the middle of the thirteenth century saw a brilliant, though brief, re vival of knowledge of the Orient. The Mongol emperort, who then ruled in China, Persia, and eastern Europe, had no strong re ligious bias, and encouraged foreign visitors and trade. -

Andrew Cook Phd Thesis V3ii

4?8J4A78D 74?DK@C?8 #*/,/&*0)0$% <K7DB;D4C<8D FB F<8 84EF =A7=4 6B@C4AK 4A7 FB F<8 47@=D4?FK 4E CG5?=E<8D2 4 64F4?B;G8 B9 5BB>E 4A7 6<4DFE HB?G@8 ===% 64F4?B;G8 52 64F4?B;G8 B9 74D?K@C?8dE 6<4DFE% H=8IE% C?4AE 4A7 7=4;D4@E% C4DF +2 */0-&*/1- 4XO[P` E' 6YYU 4 FSP\T\ E^MWT]]PO QY[ ]SP 7PR[PP YQ CS7 L] ]SP GXT_P[\T]b YQ E]' 4XO[P`\ *11, 9^VV WP]LOL]L QY[ ]ST\ T]PW T\ L_LTVLMVP TX DP\PL[NS3E]4XO[P`\29^VVFPa] L]2 S]]Z2(([P\PL[NS&[PZY\T]Y[b'\]&LXO[P`\'LN'^U( CVPL\P ^\P ]ST\ TOPX]TQTP[ ]Y NT]P Y[ VTXU ]Y ]ST\ T]PW2 S]]Z2((SOV'SLXOVP'XP](*))+,(+.,- FST\ T]PW T\ Z[Y]PN]PO Mb Y[TRTXLV NYZb[TRS] FST\ T]PW T\ VTNPX\PO ^XOP[ L 6[PL]T_P 6YWWYX\ ?TNPX\P 0 ALEXANDER DALRYMPLE (1737-1808), HYDROGRAPHER TO THE EAST INDIA COMPANY AND TO THE ADMIRALTY, AS PUBLISHER: A CATALOGUE OF BOOKS AND CHARTS ANDREW S. COOK VOLUME III CATALOGUE B: CATALOGUE OF DALRYMPLE'S ENGRAVED CHARTS, VIEWS, PLANS AND DIAGRAMS PART 2: 1784-1794 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of St. Andrews September 1992 u IN,v B354 840000 MADAGASCAR [1784 1 (Part of the coast of Madagascar, with Comoro Islands, Aldabra Islands, Farquhar Islands, Seychelles, Cargados Garajos, Mauritius and Rfiunion. -

Master of Arts Thesis Whose Goa? Projection of Goan Identity in Rival

Master of Arts Thesis Euroculture University of Groningen, the Netherlands (Home) Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic (Host) Whose Goa? Projection of Goan Identity in Rival Discourses Submitted by: Karina Kubiňáková S1842765 Gelkingestraat 47b 9711NB Groningen The Netherlands Supervised by: Dr. Margriet van der Waal (University of Groningen) doc. Jaroslav Miller, PhD (Palacký University Olomouc) Groningen, 15 February 2010 MA Programme Euroculture Declaration I, Karina Kubi ňáková, hereby declare that this thesis, entitled “Whose Goa? Projection of Goan Identity in Rival Discourses”, submitted as partial requirement for the MA Programme Euroculture, is my own original work and expressed in my own words. Any use made within it of works of authors in any form (e.g. ideas, figures, texts, tables, etc.) are properly acknowledged in the text as well as in the List of References. I hereby also acknowledge that I was informed about the regulations pertaining to the assessment of the MA thesis Euroculture and about general completion for the Master of Arts Programme Euroculture. Signed ………………………………….. Date …………………………………..15 February 2010 2 Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Portuguese overseas expansion and discovery of Goa ................................... 12 1.2 Goa as a part of the Portuguese -

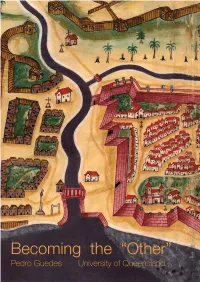

UQ684634 OA.Pdf

Pedro Guedes (2017) ‘Becoming the Other’, Lee Kah-Wee, Chang Jiat-Hwee, Imran bin Tajudeen (Convenors) M O D E R N I T Y ’ S ‘ O T H E R ’ Disclosing Southeast Asia’s Built Environment across the Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, 2nd SEAARC Symposium, National University of Singapore, 5-7 January, 2017, preprint. CONTENTS: Text 1 Presentation powerpoint slides 19 Conference abstracts & publication details 30 ABSTRACT Malacca (Melaka) entered the modern age violently on July 1st, 1511, when Afonso de Albuquerque salvoed his guns at the city as he blockaded the port. The siege was short and brutal. Its success, gained by 900 Portuguese and 200 Hindu mercenaries in eighteen ships, took the locals by complete surprise thinking the force puny compared to the 20,000 men with 20 war elephants and an impressive arsenal of artillery ranged against them. Even though the Portuguese had only been in Asia for just over a decade, they had been quick to appreciate Malacca’s strategic importance as a trading hub. A point of exchange for valuable cargoes from the archipelago to the South and Chinese ports to the East, it was located strategically between two legs of the monsoon trade cycles. Controlling the Straits fell in with Albuquerque’s ambition to regulate and tax all shipping on this route by the savage enforcement of safe-conduct navigational ‘cartazes’ to be issued by the Portuguese who considered the Indian Ocean and Asian seas as their Sovereign territory. To implement this regime, the Portuguese needed a strategically placed fortified base to assemble fleets and levy duties, enforced by superior naval gunnery and ruthless tactics. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Arabia Agreeable to Modern History . Stock#: 73441 Map Maker: Moll Date: 1729 Place: London Color: Outline Color Condition: VG+ Size: 10 x 8 inches Price: $ 450.00 Description: Finely Detailed Map of Arabia Including the Emirates, Bahrain, and Oman This aesthetically pleasing and engaging map contains a high level of detail, highlighting increased engagement between Europe and the Arabian Peninsula. The full extent of this map covers the Red Sea and part of East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula from the Mediterranean Sea to the Arabian Sea, and part of western Iran. The map shows physical features, settlements and caravan routes. The Arabian Peninsula is segmented into the Latin terms Arabia Felix, Arabia Deserta, and Arabia Petraea, as was cartographically customary at the time. A simple, square cartouche is included at bottom left, stating the title and naming “H. Moll Geographer” as the author. At top right a scale bar is included in English miles. The choice of the name "Gulph of Bassora" for the Persian Gulf is noteworthy on this map. More traditional maps of the area, particularly maps created by Islamic cartographers, typically named the Gulf after Persia and had done so for a significant amount of time. This naming is due to the commercial importance of the city of Basra, located in Iraq at the head of the Persian Gulf, in establishing trade routes between Europe and the East. English merchants had sought to secure a direct trade route from India up the Persian Gulf and through the Levant. -

Description De Java) and It Was Also Translated in Dutch As Schetsen Van Het Eiland Java in 1838

Asia Asia e-catalogue Jointly offered for sale by: Extensive descriptions and images available on request All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Antiquariaat FORUM BV ASHER Rare Books Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy 3997 ms ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E–mail: [email protected] E–mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com www.forumislamicworld.com cover image: no. 3 v 1.0 · 04 Sep 2019 Presentation copy of a very rare account of a parson’s travels through India, with a folding engraved map 1. A LLEN, William Osborn Bird. -

Conference Programme.Pdf

TIMETABLE Wed 17 July Thu 18 July Fri 19 July Sat 20 July Panel session 3 Panel session 7 12:30- 09:30- 09:30- Registration (P01, P08, P13, P19, (P05, P06, P07, 14:00 11:00 11:00 P20) P14) Panel session 1 14:00- 11:00- 11:00- (P03, P04, P09, Coffee break Coffee break 15:30 11:30 11:30 P12, P23) Panel session 4 Panel session 8 15:30- 11:30- 11:30- Coffee break (RT1, P01, P02, P10, (RT3, P06, P15, 16:00 13:00 13:00 P11, P24) P21, P22, P25) Panel session 2 Walking tours: 16:00- 13:00- 13:00- (P03, P04, P09, Lunch Lunch Chiado 10:30- 17:30 14:30 14:30 P12, P23) Baixa - Alfama 14:30- Belém 14:30- Panel session 5 Panel session 9 18.30- 14:30- (RT2, P01, P02, P10, 14:30- Keynote (RT4, P15, P16, P17, 19:30 16:00 P11, P24) 16:00 P21) 16:00- 16:00- Coffee break Coffee break 16:30 16:30 19:30- Reception Panel session 6 16:30- 16:30- Panel session 10 (P01, P02, P10, P11, 18:00 18:00 (P15, P16, P17, P21) P24) 20:00- Banquet 1st CHAM International Conference Centro de Hisória de Além-Mar, Universidade Nova de Lisboa – Universidade dos Açores, Lisbon, Portugal, 17-20 July 2013 Conference programme and book of abstracts Executive Committee: Nandini Chaturvedula, Maria João Ferreira, Jessica Hallett, Saúl Martínez Bermejo, Paulo Teodoro de Matos Scientific Committee: Manan Ahmed (Columbia University), Tamar Herzog (Stanford University), Cátia Antunes (Universiteit Leiden), Juan Marchena (Universidad Pablo de Olavide), Maxine Berg (University of Warwick), Avelino de Freitas Menezes (CHAM - UNL/UAç), Maria Fernanda Bicalho (Universidade Federal Fluminense), -

Aaron Haight Palmer

: m â t DOCUMENTS AND EACTS ILLUSTRATING THE ORIGIN OF THE MISSION TO JAPAN, AUTHORIZED BY GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES, M a y 1 0 t h , 185 1 AND WHICH FINALLY RESULTED IN THE TREATY CONCLUDED BY COMMODORE M. C. PERRY, U. S. NAVY, WITH THE JAPANESE COMMISSIONERS AT KANAGAWA, BAY OF YEDO, ON THE 3 1 s t MARCH, 1 8 5 4 . TO WHICH IS APPENDED A LIST OP THE MEMOIRS, &C., PREPARED AND SUBMITTED TO THE HON. JOHN P. KENNEDY, LATE SECRETARY OF THE NAYY, BY HIS ORDER, ON THE 26TH FEBRUARY, 1853, FOR THE USE OF THE PROJECTED U. S. EXPLORING EX PEDITION TO BEHRING’ S STRAIT, &0., UNDER THE COMMAND OF COMMANDER CADWALLADER RINGGOLD, U. S. NAYY, I BY AARON HAIGHT PALMER. WASHINGTON : HENRY POLKINHORN, PRINTER. 1857. presented to the LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • SAN DIEGO by FRIENDS OF THE LIBRARY donor DOCUMENTS AND FACTS ILLUSTRATING TIIE ORIGIN OF THE MISSION TO J1PAN, AUTHORIZED BY GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES, M a y 10t h , 1851; AND WHICH FINALLY RESULTED IN THE TREATY CONCLUDED BY COMMODORE M. C. PERRY, U.S.NAVY, WITH THE JAPANESE COMMISSIONERS AT KANAGAWA, BAY OF YEDO, ON THE 31 s t m a r c h , 1854. TO w h ic h is a p p e n d e d a l i s t o p t h e m e m o ir s , &c ., p r e p a r e d a n d ’ SUBMITTED TO THE HON. JOHN P. KENNEDY, LATE SECRETARY OF THE N AVY, BY HIS ORDER, ON THE 26 t H FEBRUARY, 1853, FOR THE USE OF THE PROJECTED U. -

A View of Ormus in 1627 Author(S): William Foster Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

A View of Ormus in 1627 Author(s): William Foster Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Aug., 1894), pp. 160-162 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1773806 Accessed: 26-06-2016 05:34 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 131.247.112.3 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 05:34:13 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms lGO .& ArIElF OF ORAIUS IN 1627. the co amencement of his magnum opus, he wrote a work entitled 'La Terre,' a tzeatise on purely physical geography, practically a preface to ' La Terre et les Hotnmes; ' and he still promises a supple- mentary volunse, to be wlitten at his ease, dealing exclusively with the human element in geoz,raphy- a di^,est and generalization of his results. He has lichly earned the right to speculate with the wealth he has created. A VIEW OF ORMUS IN 1627. By WILLIAM FOSTER. POSSIBLY some of the readers of the Geoge-aphical Journal will recollect an ancient sketch-uap of Bombay harbour, which was found a few trears ago in one of the lo^,.s of the East India Company's vessels, and was brought to notice by Sir George Birdwood in the reprint (1891) of his report on the early records of the India Office.