AN INVESTIGATION INTO the PROBLEM of OPEN URBAN SPACES in COMMUNITY PUNNING by Erich Krohmer H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on Lewis Mumford's “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford January 1962 Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History” David Riesman Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation David Riesman, Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 288 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON LEWIS MUMFORD'S 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DAVID RIESMAN* For a number of years I have not had any time to undertake book reviews but I feel so keenly the importance and excitement of Mum- ford's work, and my own personal debt to that work, that I wanted to contribute to this symposium even if I could not begin to do justice to the task. What follows are my only slightly modified notes made on reading selected chapters of the book-notes which I had hoped to have time to sift and revise for a review. I hope I can give some flavor of the book and of its author and invite readers into the corpus of Mumford's work on their own. 1. Lewis Mumford correctly says in the book that he is a generalist, not a specialist; indeed until recently he has not had (or perhaps wanted to have) a full-time academic position. -

Landscape and Urban Planning Xxx (2016) Xxx–Xxx

G Model LAND-2947; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Landscape and Urban Planning xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Thinking organic, acting civic: The paradox of planning for Cities in Evolution a,∗ b Michael Batty , Stephen Marshall a Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK b Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK h i g h l i g h t s • Patrick Geddes introduced the theory of evolution to city planning over 100 years ago. • His evolutionary theory departed from Darwin in linking collaboration to competition. • He wrestled with the tension between bottom-up and top-down action. • He never produced his magnum opus due the inherent contradictions in his philosophy. • His approach resonates with contemporary approaches to cities as complex systems. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Patrick Geddes articulated the growth and design of cities in the early years of the town planning move- Received 18 July 2015 ment in Britain using biological principles of which Darwin’s (1859) theory of evolution was central. His Received in revised form 20 April 2016 ideas about social evolution, the design of local communities, and his repeated calls for comprehensive Accepted 4 June 2016 understanding through regional survey and plan laid the groundwork for much practical planning in the Available online xxx mid 20th century, both with respect to an embryonic theory of cities and the practice of planning. -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

Organic Evolution in the Work of Lewis Mumford 5

recovering the new world dream organic evolution in the work of lewis mumford raymond h. geselbracht To turn away from the processes of life, growth, reproduc tion, to prefer the disintegrated, the accidental, the random to organic form and order is to commit collective suicide; and by the same token, to create a counter-movement to the irrationalities and threatened exterminations of our day, we must draw close once more to the healing order of nature, modified by human design. Lewis Mumford "Landscape and Townscape" in The Urban Prospect (New York, 1968) The American Adam has been forced, in the twentieth century, to change in time, to recognize the inexorable movement of history which, in his original conception, he was intended to deny. The national mythology which posited his existence has also threatened in recent decades to become absurd. This mythology, variously called the "myth of the garden" or the "Edenic myth," accepts Hector St. John de Crevecoeur's judgment, formed in the 1780's, that man in the New World of America is as a reborn Adam, innocent, virtuous, who will forever remain free of the evils of European history and civilization. "Nature" —never clearly defined, but understood as the polar opposite of what was perceived as the evil corruption and decadence of civilization in the Old World—was the great New World lap in which this mythic self-concep tion sat, the simplicity of absences which assured the American of his eternal newness. The authors who have examined this mythic complex in recent years have usually resigned themselves to its gradual senescence and demise in the twentieth century. -

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford The Autobiographical Writings ofLewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY Frank G. Novak, Jr. A Biography Monograph Publishedfor the Biographical Research Center by University of Hawaii Press General Editor: George Simson Copyright acknowledgments appear on page 64. Copyright © 1988 by the Biographical Research Center All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88—50558 ISBN 0—8248—1189—5 The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY The Autobiographical Texts I think every person of sensibility feels that he has been born “out of his due time.” Athens during the early sixth century B.C. would have been more to my liking than New York in the twentieth century after Christ. It is true, this would have cut me off from Socrates, who lived in the disappointing period that followed. But then, I might have been Socra tes! (FK 7)’ So wrote the nineteen-year-old Lewis Mumford in 1915. His bold proclamation—”I might have been Socrates!”—provides an important key to understanding the man and his life’s work. While this statement certainly reflects a good deal of idealistic and youthflul presumption, the undaunted confidence and high ambition it suggests are not merely the ingenuous boasts of callow youth. for the spirit of audacity reflected here has been an essential and enduring quality of Mum- ford’s thought and writing throughout his sixty-year career in Ameri can letters. Well before he began to establish a literary reputation, the aspiring young writer who so glibly imagines himself as Socrates reveals his profound confidence in his potential and destiny. -

A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford 1962 A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History” Daniel R. Mandelker Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Mandelker, A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 299 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVIEW OF LEWIS MUMFORD, 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DANIEL R. MANDELKER* INTRODUCTION What can a lawyer expect from a book of this kind? As a wide- ranging document of social history, it deals expansively with the form and function of the city in western civilization, from ancient times down to the present. Although Mumford is concerned in the larger sense with the city as a citadel of law and order, he is not concerned in the narrower sense with the legal structure that lies behind planning and other municipal functions. Nevertheless, the book has great value to the lawyer for the perspective it can give him. The book is diffuse. Mumford's major themes do not stand forth clearly, his preferences are merely implicit in what he says, and he certainly offers no cure-all for the ills which he sees as besetting the modern metropolis. -

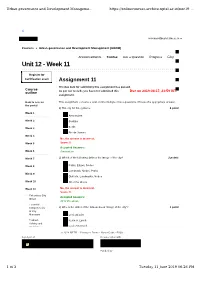

Noc19 Ar05 Assignment12

Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_... X [email protected] ▼ Courses » Urban governance and Development Management (UGDM) Announcements Course Ask a Question Progress FAQ Unit 12 - Week 11 Register for Certification exam Assignment 11 The due date for submitting this assignment has passed. Course As per our records you have not submitted this Due on 2019-04-17, 23:59 IST. outline assignment. How to access This assignment contains a total of nine multiple choice questions. Choose the appropriate answer. the portal 1) The city for the cyclist is: 1 point Week 1 Amsterdam Week 2 Curitiba Berlin Week 3 Rio de Janeiro Week 4 No, the answer is incorrect. Week 5 Score: 0 Accepted Answers: Week 6 Amsterdam Week 7 2) Which of the following defines the image of the city? 2 points Week 8 Paths, Edges, Nodes Landmark, Nodes, Paths Week 9 Districts, Landmarks, Nodes Week 10 All of the above Week 11 No, the answer is incorrect. Score: 0 Enhancing City Accepted Answers: Image All of the above Essential Competencies 3) Who is the writer of the famous book “Image of the city”? 1 point of City Managers Le Corbusier Problem Kevin A. Lynch Solving and Decision Lewis Mumford Making © 2014Jan NPTEL Gehl - Privacy & Terms - Honor Code - FAQs - Effective A project of No, the answer is incorrect. In association with Negotiation Score: 0 Communication Accepted Answers: Skills Kevin A. Lynch Funded by Quiz : 1 of 3 Tuesday 11 June 2019 06:26 PM Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_.. -

Final Final Kromer

______________________________________________________________________________ CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VACANT-PROPERTY POLICY AND PRACTICE: BALTIMORE AND PHILADELPHIA John Kromer Fels Institute of Government University of Pennsylvania A Discussion Paper Prepared for The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy and CEOs for Cities October 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY SUMMARY OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS * DISCUSSION PAPERS/RESEARCH BRIEFS 2002 Calling 211: Enhancing the Washington Region’s Safety Net After 9/11 Holding the Line: Urban Containment in the United States Beyond Merger: A Competitive Vision for the Regional City of Louisville The Importance of Place in Welfare Reform: Common Challenges for Central Cities and Remote Rural Areas Banking on Technology: Expanding Financial Markets and Economic Opportunity Transportation Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality Signs of Life: The Growth of the Biotechnology Centers in the U.S. Transitional Jobs: A Next Step in Welfare to Work Policy Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest Open Space Protection: Conservation Meets Growth Management Housing Strategies to Strengthen Welfare Policy and Support Working Families Creating a Scorecard for the CRA Service Test: Strengthening Banking Services Under the Community Reinvestment Act The Link Between Growth Management and Housing -

Town Planning & Human Settlements

AR 0416, Town Planning & Human Settlements, UNIT I INTRODUCTION TO TOWN PLANNING AND PLANNING CONCEPTS CT.Lakshmanan B.Arch., M.C.P. AP(SG)/Architecture PRESENTATION STRUCTURE INTRODUCTION PLANNING CONCEPTS • DEFINITION • GARDEN CITY – Sir Ebenezer • PLANNER’S ROLE Howard • AIMS & OBJECTIVES OF TOWN • GEDDISIAN TRIAD – Patrick Geddes PLANNING • NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING – • PLANNING PROCESS C.A.Perry • URBAN & RURAL IN INDIA • RADBURN LAYOUT • TYPES OF SURVEYS • EKISTICS • SURVEYING TECHNIQUES • SATELLITE TOWNS • DIFFERENT TYPE OF PLANS • RIBBON DEVELOPMENT TOWN PLANNING “A city should be built to give its inhbhabitants security and h”happiness” – “A place where men had a Aristotle common life for a noble end” –Plato people have the right to the city Town planning a mediation of space; making of a place WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? The art and science of ordering the use of land and siting of buildings and communication routes so as to secure the maximum practicable degree of economy, convenience, and beauty. An attempt to formulate the principles that should guide us in creating a civilized physical background for human life whose main impetus is thus … foreseeing and guiding change. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? An art of shaping and guiding the physical growth of the town creating buildings and environments to meet the various needs such as social, cultural, economic and recreational etc. and to provide healthy conditions for both rich and poor to live, to work, and to play or relax, thus bringing about the social and economic well-being for the majority of mankind. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? • physical, social and economic planning of an urban environment • It encompasses many different disciplines and brings them all under a single umbrella. -

The Importance of Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs to the Profession of Urban Planning

The Importance of Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs to the Profession of Urban Planning Matthias Wendt New Visions for Public Affairs – Volume 1, Spring 2009 School of Urban Affairs and Public Policy – University of Delaware, Newark, DE www.suapp.udel.edu/nvpa/home Wendt, Matthias Death and Life by Jane Jacobs 1 he Death and Life of Great American Cities, impact of the book on the profession of urban planning. which will be hereafter referred to as Death In addition, Jane Jacobs’ influence on the New T and Life, was the first and most influential Urbanism movement is explored, and her concepts are book by Jane Jacobs, a writer and city activist from finally applied to the Atlantic Yards Project, a large- New York City. The book was first published in 1961 scale urban redevelopment project in Brooklyn, New and it frontally attacked the principles and objectives of York. modernist, orthodox city planning and rebuilding in the post-war U.S. I. Urban Planning and U.S. Cities in the Post-War Death and Life is a reaction to the devastating results of Period post-war American urban renewal. Jacobs’ 1961 landmark critique directly attacks what she calls Jane Jacobs evolved the ideas set forth in Death and “orthodox” city planning and rebuilding. She Life as a young mother living in New York’s documents the failures of modernist planning ideas and Greenwich Village during the postwar period, when the argues that the various foundations of intellectual big American cities were in a state of crisis. -

Narrative Sample

RSCA 2014 Narrative Applicant Anthony Raynsford, Department of Art and Art History Project Proposal: Scale, Perception and Experience in Postwar American Urban Design p. I of 3 Dear Members of the Selection Committee, The Origins of This Project: In September 2013, Robert Lockhart, acquisitions editor for the University of Pennsylvania Press, contacted me about authoring a book in their series, The Arts and Intellectual Life in Modern America. At the time I had already been working on a book manuscript entitled, Modernism and the Archaic City: The Pre Industrial Past in the Imagination of 20th Century Urban Design, but was finding that the scope was too broad and ambitious, given the time and resources available to me to write the manuscript. I had tentatively already decided to publish certain individual chapters as articles instead of pursuing the book further. However, at our meeting in early October, Lockhart persuaded me that a portion of that manuscript, now much more narrowly focused on the United States in the immediate postwar period would make a compelling book project for their series. He then asked me to submit for them three sample chapters and a formal book proposal for preliminary review. The scope of this project now involves a much more detailed intellectual biography of leading figures in postwar American urban design, requiring some additional archival research. I plan to complete the formal proposal by early spring but would then require the rest of the spring and the early summer to complete the sample chapters and finish the research. The RSCA grant would allow me to complete this research during the summer and to submit the formal proposal and chapters by September. -

Reflecting on the Legacy of Kevin Lynch's Cognitive Approach to City

Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 12 (2018) 778-797 D doi: 10.17265/1934-7359/2018.11.002 DAVID PUBLISHING Reflecting on the Legacy of Kevin Lynch’s Cognitive Approach to City Design through Italian Didactic Experiences Elena Marchigiani1 and Claudia Mattogno2 1. Department of Engineering and Architecture, University of Trieste, Trieste 34127, Italy 2. Department of Civil, Building and Environmental Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome 00184, Italy Abstract: In Italy, the writings of Kevin Lynch (1918-1984) have had great influence. However, if The Image of the City (1960, trans. 1964) enjoyed a prolonged success, other texts attracted a fluctuating attention. The reasons for this variable interest help reflect on the current usability of Lynch’s lesson: the relevance given to social perception; the need to give voice to citizens’ needs; a performance approach to the project as a participatory process. The ability to stimulate a reflective attitude explains why, in Italy, Lynch’s legacy has found its major expression in teaching. Recent experiences at the Universities of Rome and Trieste – also suggested by the Lynch’s centennial – show how his texts still constitute a reference to approach urban analysis and design, being completely involved in the physical perception of the places and listening to the inhabitants’ stories. Didactic activities highlight further exploitation of Lynch’s theory in terms of: the importance of learning by interaction; a better understanding of urban space and social practices; the drawing of projects from mental maps. Nonetheless, when working in the historical parts of Italian cities, the character and uses of urban spaces urge us to adjust Lynch’s categories, thus, in fact, confirming their critical capacity and timeliness.