Final Final Kromer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on Lewis Mumford's “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford January 1962 Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History” David Riesman Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation David Riesman, Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 288 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON LEWIS MUMFORD'S 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DAVID RIESMAN* For a number of years I have not had any time to undertake book reviews but I feel so keenly the importance and excitement of Mum- ford's work, and my own personal debt to that work, that I wanted to contribute to this symposium even if I could not begin to do justice to the task. What follows are my only slightly modified notes made on reading selected chapters of the book-notes which I had hoped to have time to sift and revise for a review. I hope I can give some flavor of the book and of its author and invite readers into the corpus of Mumford's work on their own. 1. Lewis Mumford correctly says in the book that he is a generalist, not a specialist; indeed until recently he has not had (or perhaps wanted to have) a full-time academic position. -

Landscape and Urban Planning Xxx (2016) Xxx–Xxx

G Model LAND-2947; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Landscape and Urban Planning xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Thinking organic, acting civic: The paradox of planning for Cities in Evolution a,∗ b Michael Batty , Stephen Marshall a Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK b Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK h i g h l i g h t s • Patrick Geddes introduced the theory of evolution to city planning over 100 years ago. • His evolutionary theory departed from Darwin in linking collaboration to competition. • He wrestled with the tension between bottom-up and top-down action. • He never produced his magnum opus due the inherent contradictions in his philosophy. • His approach resonates with contemporary approaches to cities as complex systems. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Patrick Geddes articulated the growth and design of cities in the early years of the town planning move- Received 18 July 2015 ment in Britain using biological principles of which Darwin’s (1859) theory of evolution was central. His Received in revised form 20 April 2016 ideas about social evolution, the design of local communities, and his repeated calls for comprehensive Accepted 4 June 2016 understanding through regional survey and plan laid the groundwork for much practical planning in the Available online xxx mid 20th century, both with respect to an embryonic theory of cities and the practice of planning. -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191. -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

Inner Harbor West

URBAN RENEWAL PLAN INNER HARBOR WEST DISCLAIMER: The following document has been prepared in an electronic format which permits direct printing of the document on 8.5 by 11 inch dimension paper. If the reader intends to rely upon provisions of this Urban Renewal Plan for any lawful purpose, please refer to the ordinances, amending ordinances and minor amendments relevant to this Urban Renewal Plan. While reasonable effort will be made by the City of Baltimore Development Corporation to maintain current status of this document, the reader is advised to be aware that there may be an interval of time between the adoption of any amendment to this document, including amendment(s) to any of the exhibits or appendix contained in the document, and the incorporation of such amendment(s) in the document. By printing or otherwise copying this document, the reader hereby agrees to recognize this disclaimer. INNER HARBOR WEST URBAN RENEWAL PLAN DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND ORIGINALLY APPROVED BY THE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE BY ORDINANCE NO. 1007 MARCH 15, 1971 AMENDMENTS ADDED ON THIS PAGE FOR CLARITY NOVEMBER, 2004 I. Amendment No. 1 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance 289, dated April 2, 1973. II. Amendment No. 2 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. 356, dated June 27, 1977. III. (Minor) Amendment No. 3 approved by the Board of Estimates on June 7, 1978. IV. Amendment No. 4 approved by the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore by Ordinance No. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

Organic Evolution in the Work of Lewis Mumford 5

recovering the new world dream organic evolution in the work of lewis mumford raymond h. geselbracht To turn away from the processes of life, growth, reproduc tion, to prefer the disintegrated, the accidental, the random to organic form and order is to commit collective suicide; and by the same token, to create a counter-movement to the irrationalities and threatened exterminations of our day, we must draw close once more to the healing order of nature, modified by human design. Lewis Mumford "Landscape and Townscape" in The Urban Prospect (New York, 1968) The American Adam has been forced, in the twentieth century, to change in time, to recognize the inexorable movement of history which, in his original conception, he was intended to deny. The national mythology which posited his existence has also threatened in recent decades to become absurd. This mythology, variously called the "myth of the garden" or the "Edenic myth," accepts Hector St. John de Crevecoeur's judgment, formed in the 1780's, that man in the New World of America is as a reborn Adam, innocent, virtuous, who will forever remain free of the evils of European history and civilization. "Nature" —never clearly defined, but understood as the polar opposite of what was perceived as the evil corruption and decadence of civilization in the Old World—was the great New World lap in which this mythic self-concep tion sat, the simplicity of absences which assured the American of his eternal newness. The authors who have examined this mythic complex in recent years have usually resigned themselves to its gradual senescence and demise in the twentieth century. -

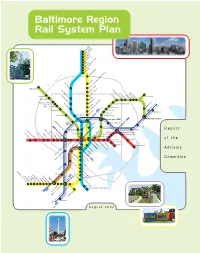

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford The Autobiographical Writings ofLewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY Frank G. Novak, Jr. A Biography Monograph Publishedfor the Biographical Research Center by University of Hawaii Press General Editor: George Simson Copyright acknowledgments appear on page 64. Copyright © 1988 by the Biographical Research Center All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88—50558 ISBN 0—8248—1189—5 The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY The Autobiographical Texts I think every person of sensibility feels that he has been born “out of his due time.” Athens during the early sixth century B.C. would have been more to my liking than New York in the twentieth century after Christ. It is true, this would have cut me off from Socrates, who lived in the disappointing period that followed. But then, I might have been Socra tes! (FK 7)’ So wrote the nineteen-year-old Lewis Mumford in 1915. His bold proclamation—”I might have been Socrates!”—provides an important key to understanding the man and his life’s work. While this statement certainly reflects a good deal of idealistic and youthflul presumption, the undaunted confidence and high ambition it suggests are not merely the ingenuous boasts of callow youth. for the spirit of audacity reflected here has been an essential and enduring quality of Mum- ford’s thought and writing throughout his sixty-year career in Ameri can letters. Well before he began to establish a literary reputation, the aspiring young writer who so glibly imagines himself as Socrates reveals his profound confidence in his potential and destiny. -

A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford 1962 A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History” Daniel R. Mandelker Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Mandelker, A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 299 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVIEW OF LEWIS MUMFORD, 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DANIEL R. MANDELKER* INTRODUCTION What can a lawyer expect from a book of this kind? As a wide- ranging document of social history, it deals expansively with the form and function of the city in western civilization, from ancient times down to the present. Although Mumford is concerned in the larger sense with the city as a citadel of law and order, he is not concerned in the narrower sense with the legal structure that lies behind planning and other municipal functions. Nevertheless, the book has great value to the lawyer for the perspective it can give him. The book is diffuse. Mumford's major themes do not stand forth clearly, his preferences are merely implicit in what he says, and he certainly offers no cure-all for the ills which he sees as besetting the modern metropolis. -

Noc19 Ar05 Assignment12

Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_... X [email protected] ▼ Courses » Urban governance and Development Management (UGDM) Announcements Course Ask a Question Progress FAQ Unit 12 - Week 11 Register for Certification exam Assignment 11 The due date for submitting this assignment has passed. Course As per our records you have not submitted this Due on 2019-04-17, 23:59 IST. outline assignment. How to access This assignment contains a total of nine multiple choice questions. Choose the appropriate answer. the portal 1) The city for the cyclist is: 1 point Week 1 Amsterdam Week 2 Curitiba Berlin Week 3 Rio de Janeiro Week 4 No, the answer is incorrect. Week 5 Score: 0 Accepted Answers: Week 6 Amsterdam Week 7 2) Which of the following defines the image of the city? 2 points Week 8 Paths, Edges, Nodes Landmark, Nodes, Paths Week 9 Districts, Landmarks, Nodes Week 10 All of the above Week 11 No, the answer is incorrect. Score: 0 Enhancing City Accepted Answers: Image All of the above Essential Competencies 3) Who is the writer of the famous book “Image of the city”? 1 point of City Managers Le Corbusier Problem Kevin A. Lynch Solving and Decision Lewis Mumford Making © 2014Jan NPTEL Gehl - Privacy & Terms - Honor Code - FAQs - Effective A project of No, the answer is incorrect. In association with Negotiation Score: 0 Communication Accepted Answers: Skills Kevin A. Lynch Funded by Quiz : 1 of 3 Tuesday 11 June 2019 06:26 PM Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_..