Organic Evolution in the Work of Lewis Mumford 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on Lewis Mumford's “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford January 1962 Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History” David Riesman Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation David Riesman, Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 288 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON LEWIS MUMFORD'S 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DAVID RIESMAN* For a number of years I have not had any time to undertake book reviews but I feel so keenly the importance and excitement of Mum- ford's work, and my own personal debt to that work, that I wanted to contribute to this symposium even if I could not begin to do justice to the task. What follows are my only slightly modified notes made on reading selected chapters of the book-notes which I had hoped to have time to sift and revise for a review. I hope I can give some flavor of the book and of its author and invite readers into the corpus of Mumford's work on their own. 1. Lewis Mumford correctly says in the book that he is a generalist, not a specialist; indeed until recently he has not had (or perhaps wanted to have) a full-time academic position. -

Landscape and Urban Planning Xxx (2016) Xxx–Xxx

G Model LAND-2947; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Landscape and Urban Planning xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Thinking organic, acting civic: The paradox of planning for Cities in Evolution a,∗ b Michael Batty , Stephen Marshall a Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK b Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK h i g h l i g h t s • Patrick Geddes introduced the theory of evolution to city planning over 100 years ago. • His evolutionary theory departed from Darwin in linking collaboration to competition. • He wrestled with the tension between bottom-up and top-down action. • He never produced his magnum opus due the inherent contradictions in his philosophy. • His approach resonates with contemporary approaches to cities as complex systems. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Patrick Geddes articulated the growth and design of cities in the early years of the town planning move- Received 18 July 2015 ment in Britain using biological principles of which Darwin’s (1859) theory of evolution was central. His Received in revised form 20 April 2016 ideas about social evolution, the design of local communities, and his repeated calls for comprehensive Accepted 4 June 2016 understanding through regional survey and plan laid the groundwork for much practical planning in the Available online xxx mid 20th century, both with respect to an embryonic theory of cities and the practice of planning. -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

Module 3.2: Paradigms of Urban Planning

Module 3.2: Paradigms of Urban Planning Role Name Affiliation National Coordinator Subject Prof Sujata Patel Department of Sociology, Coordinator University of Hyderabad Paper Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Coordinator Indian Institute of Technology, Mandi Surya Prakash Content Writer Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Content Reviewer Prof Sanjeev Vidyarthi University of Illinois-Chicago Language Editor Ashima Sood Woxsen School of Business Technical Conversion Module Structure Sections and headings Introduction Planning Paradigms in the Anglophone World The Garden City 1 Neighbourhood unit as concept and planning practice Jane Jacobs New Urbanism Geddes in India Ideas in Practice Spatial planning in post-colonial India Modernism in the Indian city Neighbourhood unit in India In Brief For Further Reading Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Sociology of Urban Transformation Module Name/Title Paradigms of urban planning Module Id 3.2 Pre Requisites Objectives To develop an understanding of select urban planning paradigms in the Anglophone world To trace the influences and dominant frameworks guiding urban planning in contemporary India To critically evaluate the contributions of 2 planning paradigms to the present condition of Indian cities Key words Garden city; neighbourhood unit; New Urbanism; modernism in India; Jane Jacobs; Patrick Geddes (5-6 words/phrases) Introduction Indian cities are characterized by visual dissonance and stark juxtapositions of poverty and wealth. “If only the city was properly planned,” goes the refrain in response, whether in media, official and everyday discourse. Yet, this invocation of city planning, rarely harkens to the longstanding traditions of Indian urbanism – the remarkable drainage networks and urban accomplishments of the Indus Valley cities, the ghats of Varanasi, or the chowks and bazars of Shahjanahabad. -

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford

The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford The Autobiographical Writings ofLewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY Frank G. Novak, Jr. A Biography Monograph Publishedfor the Biographical Research Center by University of Hawaii Press General Editor: George Simson Copyright acknowledgments appear on page 64. Copyright © 1988 by the Biographical Research Center All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 88—50558 ISBN 0—8248—1189—5 The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford A STUDY IN LITERARY AUDACITY The Autobiographical Texts I think every person of sensibility feels that he has been born “out of his due time.” Athens during the early sixth century B.C. would have been more to my liking than New York in the twentieth century after Christ. It is true, this would have cut me off from Socrates, who lived in the disappointing period that followed. But then, I might have been Socra tes! (FK 7)’ So wrote the nineteen-year-old Lewis Mumford in 1915. His bold proclamation—”I might have been Socrates!”—provides an important key to understanding the man and his life’s work. While this statement certainly reflects a good deal of idealistic and youthflul presumption, the undaunted confidence and high ambition it suggests are not merely the ingenuous boasts of callow youth. for the spirit of audacity reflected here has been an essential and enduring quality of Mum- ford’s thought and writing throughout his sixty-year career in Ameri can letters. Well before he began to establish a literary reputation, the aspiring young writer who so glibly imagines himself as Socrates reveals his profound confidence in his potential and destiny. -

A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford 1962 A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History” Daniel R. Mandelker Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Mandelker, A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 299 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVIEW OF LEWIS MUMFORD, 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DANIEL R. MANDELKER* INTRODUCTION What can a lawyer expect from a book of this kind? As a wide- ranging document of social history, it deals expansively with the form and function of the city in western civilization, from ancient times down to the present. Although Mumford is concerned in the larger sense with the city as a citadel of law and order, he is not concerned in the narrower sense with the legal structure that lies behind planning and other municipal functions. Nevertheless, the book has great value to the lawyer for the perspective it can give him. The book is diffuse. Mumford's major themes do not stand forth clearly, his preferences are merely implicit in what he says, and he certainly offers no cure-all for the ills which he sees as besetting the modern metropolis. -

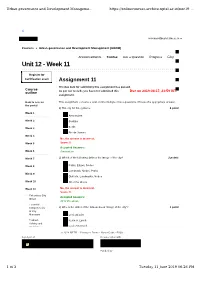

Noc19 Ar05 Assignment12

Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_... X [email protected] ▼ Courses » Urban governance and Development Management (UGDM) Announcements Course Ask a Question Progress FAQ Unit 12 - Week 11 Register for Certification exam Assignment 11 The due date for submitting this assignment has passed. Course As per our records you have not submitted this Due on 2019-04-17, 23:59 IST. outline assignment. How to access This assignment contains a total of nine multiple choice questions. Choose the appropriate answer. the portal 1) The city for the cyclist is: 1 point Week 1 Amsterdam Week 2 Curitiba Berlin Week 3 Rio de Janeiro Week 4 No, the answer is incorrect. Week 5 Score: 0 Accepted Answers: Week 6 Amsterdam Week 7 2) Which of the following defines the image of the city? 2 points Week 8 Paths, Edges, Nodes Landmark, Nodes, Paths Week 9 Districts, Landmarks, Nodes Week 10 All of the above Week 11 No, the answer is incorrect. Score: 0 Enhancing City Accepted Answers: Image All of the above Essential Competencies 3) Who is the writer of the famous book “Image of the city”? 1 point of City Managers Le Corbusier Problem Kevin A. Lynch Solving and Decision Lewis Mumford Making © 2014Jan NPTEL Gehl - Privacy & Terms - Honor Code - FAQs - Effective A project of No, the answer is incorrect. In association with Negotiation Score: 0 Communication Accepted Answers: Skills Kevin A. Lynch Funded by Quiz : 1 of 3 Tuesday 11 June 2019 06:26 PM Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_.. -

From Darwinism to Planning – Through Geddes and Back

from darwinism to planning – through geddes and back One hundred and fifty years after the publication of On the Origin of Species, urban theorists are giving renewed attention to Darwinian interpretations of urban change, beyond those pioneered by Patrick Geddes over a century ago. Stephen Marshall and Michael Batty suggest some implications for urbanism and planning Since the publication of On the Origin of Species Patrick Geddes – biologist turned town 150 years ago this month,1 Darwin’s theory of planner evolution has not only had a revolutionary impact on Geddes originally trained as a biologist, somewhat natural history and the life sciences, but has also unconventionally under the tutelage of his mentor helped to prompt the emergence of disciplines such Thomas Huxley in the 1870s in London, where he as ecology, sociobiology and evolutionary also met Darwin. Although his interests in civics psychology. It has also given rise to evolutionary and sociology dominated his working life, his belief interpretations of topics as diverse as linguistics, in evolution as the underpinning science of cities economics and the history of technology. culminated in his book Cities in Evolution, published Evolutionary theory has even had an impact on the in 1915.2 field of town planning, principally through the Yet Geddes’ own ideology of planning was fraught pioneering work of Patrick Geddes. with tensions, apparent in the conflict between However, while Geddes’ planning ideas are well solving social problems collectively from the top known, his biological theories are much less well down and the workings of evolutionary processes understood. In fact, Geddes’ view of biological which suggest that fitness for purpose emerges evolution differed substantially from Darwin’s, and from the bottom up. -

Final Final Kromer

______________________________________________________________________________ CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VACANT-PROPERTY POLICY AND PRACTICE: BALTIMORE AND PHILADELPHIA John Kromer Fels Institute of Government University of Pennsylvania A Discussion Paper Prepared for The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy and CEOs for Cities October 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY SUMMARY OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS * DISCUSSION PAPERS/RESEARCH BRIEFS 2002 Calling 211: Enhancing the Washington Region’s Safety Net After 9/11 Holding the Line: Urban Containment in the United States Beyond Merger: A Competitive Vision for the Regional City of Louisville The Importance of Place in Welfare Reform: Common Challenges for Central Cities and Remote Rural Areas Banking on Technology: Expanding Financial Markets and Economic Opportunity Transportation Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality Signs of Life: The Growth of the Biotechnology Centers in the U.S. Transitional Jobs: A Next Step in Welfare to Work Policy Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest Open Space Protection: Conservation Meets Growth Management Housing Strategies to Strengthen Welfare Policy and Support Working Families Creating a Scorecard for the CRA Service Test: Strengthening Banking Services Under the Community Reinvestment Act The Link Between Growth Management and Housing -

Town Planning & Human Settlements

AR 0416, Town Planning & Human Settlements, UNIT I INTRODUCTION TO TOWN PLANNING AND PLANNING CONCEPTS CT.Lakshmanan B.Arch., M.C.P. AP(SG)/Architecture PRESENTATION STRUCTURE INTRODUCTION PLANNING CONCEPTS • DEFINITION • GARDEN CITY – Sir Ebenezer • PLANNER’S ROLE Howard • AIMS & OBJECTIVES OF TOWN • GEDDISIAN TRIAD – Patrick Geddes PLANNING • NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING – • PLANNING PROCESS C.A.Perry • URBAN & RURAL IN INDIA • RADBURN LAYOUT • TYPES OF SURVEYS • EKISTICS • SURVEYING TECHNIQUES • SATELLITE TOWNS • DIFFERENT TYPE OF PLANS • RIBBON DEVELOPMENT TOWN PLANNING “A city should be built to give its inhbhabitants security and h”happiness” – “A place where men had a Aristotle common life for a noble end” –Plato people have the right to the city Town planning a mediation of space; making of a place WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? The art and science of ordering the use of land and siting of buildings and communication routes so as to secure the maximum practicable degree of economy, convenience, and beauty. An attempt to formulate the principles that should guide us in creating a civilized physical background for human life whose main impetus is thus … foreseeing and guiding change. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? An art of shaping and guiding the physical growth of the town creating buildings and environments to meet the various needs such as social, cultural, economic and recreational etc. and to provide healthy conditions for both rich and poor to live, to work, and to play or relax, thus bringing about the social and economic well-being for the majority of mankind. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? • physical, social and economic planning of an urban environment • It encompasses many different disciplines and brings them all under a single umbrella. -

Las Escuelas Nacionales De Arte De La Habana

En el límite de la arquitectura-paisaje Las Escuelas Nacionales de Arte de La Habana Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Departamento de Proyectos Arquitectónicos Tesis doctoral Autora: María José Pizarro Juanas, arquitecto Director: José González Gallegos, doctor arquitecto 2012 Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Tribunal nombrado por el Mgfco. Y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día ................................................................. Presidente D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Secretario D. Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de Tesis En el límite de la arquitectura- paisaje. Las Escuelas Nacionales de Arte de La Habana el día .................... ........................de 2012, en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Califi cación: EL PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO A Mara, Álvaro y Óscar Indice 10 AGRADECIMIENTOS 12 RESUMEN 15 INTRODUCCIÓN 23 CRONOLOGÍA Capítulo I. HISTORIA DE UN ENCARGO: UNA ACADEMIA DE LAS ARTES PARA LOS HIJOS DE LOS TRABAJADORES 33 • UNA PARTIDA DE GOLF EN EL HAVANA COUNTRY CLUB. ENERO 1961 45 • UN VIAJE FORMATIVO. 1950ͳ1961 47 La Habana. 1950 53 Venecia. 1951 63 Milán. 1952 67 Caracas. 1957 73 La Habana. 1960 77 • LAS PREEXISTENCIAS CULTURALES: LA HABANA 1900ͳ1961 79 La Habana de principios de siglo 85 La Habana moderna. Entre la tradición y la modernidad 95 La Habana de los primeros años de la revolución Capítulo II. LOS PRINCIPIOS INTEGRADORES: PAISAJE, MATERIALIDAD Y SISTEMA CONSTRUCTIVO 105 • LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DE UN PAISAJE PARA LA REVOLUCIÓN 107 I. De la naturaleza al paisaje: el arquitecto paisajista 121 Del paisaje público al paisaje social: Olmsted y Burle-Marx 131 Del paisaje cultural a la búsqueda de la idenƟ dad nacional 145 II. -

The Evolutionary Spirit at Work in Patrick Geddes

Geddes Institute for Urban Research University of Dundee Working Paper [This Research Paper was developed in part to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the publication of Cities in Evolution. It formed the background for a presentation at the University on November 20th, 2015, as part of the programming that complemented the exhibition, The City is a Thinking Machine. The paper is offered here in part to explore interest in an idea advanced in the paper, namely, the call for an ‘integral biography’ of Patrick Geddes. Prospective collaborators are invited to contact [email protected]] The Evolutionary Spirit at Work In Patrick Geddes Ian Wight PhD, Senior Scholar, City Planning Faculty of Architecture, University of Manitoba <[email protected]> Abstract: A larger than life presence in his day, the influence of Patrick Geddes lives on in the present. Many fields have felt his influence and acknowledge his, often formative, contribution. What was the spirit that powered him then – to such heights, and breadths and depths; that was embodied in his thinking and acting – and ‘machine-making’ - that might be tapped afresh? In particular, what might admirers have missed or downplayed, because they were not so spiritually attuned, nor so integrated in their beliefs and convictions? What does the Geddes then, say to us today; that merits our attention; that might cause us to revise our intentions - in regard to our practice dispositions and operating systems? This presentation offers an integral perspective on such lines of questioning. Looking at Geddes afresh through an integral lens yields some intriguing insights. There have been integral, holistic influences at work, philosophically, for centuries – but they have mostly, especially in the recent century, been highly subordinate to more exclusively scientific perspectives, associated with differentiation, and reductionism.