The Autobiographical Writings of Lewis Mumford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on Lewis Mumford's “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford January 1962 Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History” David Riesman Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation David Riesman, Some Observations on Lewis Mumford’s “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 288 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME OBSERVATIONS ON LEWIS MUMFORD'S 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DAVID RIESMAN* For a number of years I have not had any time to undertake book reviews but I feel so keenly the importance and excitement of Mum- ford's work, and my own personal debt to that work, that I wanted to contribute to this symposium even if I could not begin to do justice to the task. What follows are my only slightly modified notes made on reading selected chapters of the book-notes which I had hoped to have time to sift and revise for a review. I hope I can give some flavor of the book and of its author and invite readers into the corpus of Mumford's work on their own. 1. Lewis Mumford correctly says in the book that he is a generalist, not a specialist; indeed until recently he has not had (or perhaps wanted to have) a full-time academic position. -

Landscape and Urban Planning Xxx (2016) Xxx–Xxx

G Model LAND-2947; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Landscape and Urban Planning xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan Thinking organic, acting civic: The paradox of planning for Cities in Evolution a,∗ b Michael Batty , Stephen Marshall a Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK b Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK h i g h l i g h t s • Patrick Geddes introduced the theory of evolution to city planning over 100 years ago. • His evolutionary theory departed from Darwin in linking collaboration to competition. • He wrestled with the tension between bottom-up and top-down action. • He never produced his magnum opus due the inherent contradictions in his philosophy. • His approach resonates with contemporary approaches to cities as complex systems. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Patrick Geddes articulated the growth and design of cities in the early years of the town planning move- Received 18 July 2015 ment in Britain using biological principles of which Darwin’s (1859) theory of evolution was central. His Received in revised form 20 April 2016 ideas about social evolution, the design of local communities, and his repeated calls for comprehensive Accepted 4 June 2016 understanding through regional survey and plan laid the groundwork for much practical planning in the Available online xxx mid 20th century, both with respect to an embryonic theory of cities and the practice of planning. -

Laura López Peña Walt Whitman and Herman Melville.Pdf

Màster en Construcció i representació d’identitats culturals (Curs 2007/2008) Especialitat: Estudis de parla anglesa The Role of the Poet in the American Civil War: Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps (1865) and Herman Melville’s Battle-Pieces (1866) TREBALL DE RECERCA Laura López Peña Tutor: Dr. Rodrigo Andrés González Universitat de Barcelona Barcelona, setembre 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 WALT WHITMAN’S DRUM-TAPS (1865) 1.1 Introduction 8 1.2 “[M]y book and the war are one” 10 1.3 The Poet as Instructor and Wound-Dresser 14 1.4 Whitman’s Insight of the War: The Washington Years 17 1.5 The Structure of Drum-Taps : Whitman’s 1891-92 Arrangement 21 1.6 The Reception of Drum-Taps 27 HERMAN MELVILLE’S BATTLE-PIECES (1866) 1.1 Introduction 30 1.2 America’s Enlightening Nightmare: Melville’s Perception of the Civil War 33 1.3 Melville, Poet? 35 1.4 Herman Melville and the Civil War 37 1.5 The Structure of Battle-Pieces : A Symmetrical Asymmetry 42 1.6 The Poet as Mediator: The “Supplement” to Battle-Pieces 50 1.7 The Reception of Battle-Pieces 52 CONCLUSIONS: COMPARING DRUM-TAPS AND BATTLE-PIECES 1.1 Introduction 55 1.2 Why Poetry? What Poetry? 56 1.3 Immediacy vs. Historical Perspective; Praying vs. Warning 60 1.4 The Role of the Poet 64 WORKS CITED 69 To them who crossed the flood And climbed the hill, with eyes Upon the heavenly flag intent, And through the deathful tumult went Even unto death: to them this Stone— Erect, where they were overthrown— Of more than victory the monument. -

ANALYSIS Typee

ANALYSIS Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life During a Four Months’ Residence in a Valley of the Marquesas (1846) Herman Melville (1819-1891) “Whether the natives are actually maneaters or noble savages, enemies or friends, is a doubt sustained to the very end. At all events, they are the most ‘humane, gentlemanly, and amiable set of epicures’ that the narrator has ever encountered. He is welcomed by mermaids with jet-black tresses, feasted and cured of his wound, and allowed to go canoeing with Fayaway, a less remote enchantress than her name suggests. But danger looms behind felicity; ambiguous forebodings, epicurean but inhumane, reverberate from the heathen idols in the taboo groves; and the narrator escapes to a ship, as he had escaped from another one at the outset…. He has tasted the happiness of the pastoral state. He has enjoyed the primitive condition, as it had been idealized by Rousseau… As for clothes, they wear little more than ‘the garb of Eden’; and Melville…is tempted to moralize over how unbecoming the same costume might look on the civilized. Where Poe’s black men were repulsive creatures, Melville is esthetically entranced by the passionate dances of the Polynesians; and his racial consciousness begins to undergo a radical transposition when he envisions them as pieces of ‘dusky statuary.’ On the whole, he believes, ‘the penalty of the fall presses very lightly upon the valley of Typee.’… If there is any serpent in the Marquesan garden, it is the contaminating contact of the white men. If the children of nature are losing their innocence, that is to be blamed upon their would-be civilizers. -

Designing Cities, Planning for People

Designing cities, planning for people The guide books of Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon Minna Chudoba Tampere University of Technology School of Architecture [email protected] Abstract Urban theorists and critics write with an individual knowledge of the good urban life. Recently, writing about such life has boldly called for smart cities or even happy cities, stressing the importance of social connections and nearness to nature, or social and environmental capital. Although modernist planning has often been blamed for many current urban problems, the social and the environmental dimensions were not completely absent from earlier 20th century approaches to urban planning. Links can be found between the urban utopia of today and the mid-20th century ideas about good urban life. Changes in the ideas of what constitutes good urban life are investigated in this paper through two texts by two different 20th century planners: Otto-Iivari Meurman and Edmund Bacon. Both were taught by the Finnish planner Eliel Saarinen, and according to their teacher’s example, also wrote about their planning ideas. Meurman’s guide book for planners was published in 1947, and was a major influence on Finnish post-war planning. In Meurman’s case, the book answered a pedagogical need, as planners were trained to meet the demands of the structural changes of society and the needs of rapidly growing Finnish cities. Bacon, in a different context, stressed the importance of an urban design attitude even when planning the movement systems of a modern metropolis. Bacon’s book from 1967 was meant for both designers and city dwellers, exploring the dynamic nature of modern urbanity. -

Melville's Quarrel with the Transcendentalists

-. MELVILLE'S QUARREL WITH THE TRANSCENDENTALISTS A Monograph Pl:>esented to the Faculty of the Department of English Morehead State University ' . In Partial Fulfillmen~ of the Requirements for the Degree ''I Master-of Al>ts by Ina Marie Lowe August 1970 ' Accepted by the faculty of the School. of ft,,._11114.4 ; f:i~ 5 • Morehead State University, in partial. fulfil.l.ment of the require- ments for the Master of _ _,_A,.l'.._t".._.:i._ ____ degree, TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Introduction . ••...••..••.•.••..••.•.•........•..•.• , .•.•.•• l II. Melville and Transcendental Idealism ••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 III. Melville and Transcendental Intellectualism •••••••••••••••••• 18 IV. Melville and 'l'X'anscendental Optimism and Innocence ••••••••• 36 v. Summary and Conclusion ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 56 BIBLIOGRAPHY • •••••••••••• , ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• , , •••••• , • , • 59 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Melvill.e has usually been considered either as one of the Trans cendental writers or as having been influenced by Transcendental thought. There has been a critical acceptance of the thesis that Melville began as a Transcendentalist; then, as he grew older and presumably less wise in the romantic sense, he eschewed his early idealism and opted for an acceptance of moral expediency and com plicity. The beginning hypothesis of this study will be that Melville, although he could be said to share some of Transcendentalism's secondary ideas and attitudes, objected to many of the Transcend alists' most cherished beliefs. In fact, one can say that, rather than being a Transcendentalist writer, Melville was an anti Transcendentalist writer, constitutionally and intellectuall.y unable to accept the Transcendental view of life. In advancing the argument of this study, the critical works of Melvillean scholars will be considered for the light they may throw upon Transcendental influence on Melville's work. -

"No Life You Have Known": Or, Melville's Contemporary Critics Hester Blum

"No Life You Have Known": Or, Melville's Contemporary Critics Hester Blum Leviathan, Volume 13, Issue 1, March 2011, pp. 10-20 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/493026/summary Access provided at 9 Apr 2019 00:59 GMT from Penn State Univ Libraries “No Life You Have Known”: Or, Melville’s Contemporary Critics HESTER BLUM The Pennsylvania State University id-nineteenth century evaluations of Herman Melville’s work share acommonattentiontowhatmanyreviewers—anditcanseem Mlike all of them—called the “extravagance” of his writing and his imagination. Critics remarked on his general “love of antic and extravagant speculation” (O’Brien 389) and found that his imagination had a “tendency to wildness and metaphysical extravagance” (Hawthorne and Lemmon 208). In their estimation the “extravagant” Mardi featured “incredibly extravagant disguises” (“Trio” 462) and contained “a world of extravagant phantoms and allegorical shades” (Chasles 262), while Redburn was notable for “episodic extravaganzas” (“Sir Nathaniel” 453). “Unlicensed extravagance” (454) char- acterized even White-Jacket;and“theextravaganttreatment”(454)givento whaling in Moby-Dick stood in for the novel’s “eccentric and monstrously extravagant” nature (“Trio” 463), containing as it did “reckless, inconceivable extravagancies” (“Trio” 463) in addition to “purposeless extravagance” (A.B.R. 364). These surpassed the only “passable extravagancies” of his earlier works (“Book Notices” 93). The critical account offered above was assembled from fragments of criticism of the novels of Melville’s mid-career; readers of Pierre will hear in it the echo of Mary Glendinning’s equally insistent—and equally regulatory— catalogue of her son’s qualities: “A noble boy, and docile.. -

Organic Evolution in the Work of Lewis Mumford 5

recovering the new world dream organic evolution in the work of lewis mumford raymond h. geselbracht To turn away from the processes of life, growth, reproduc tion, to prefer the disintegrated, the accidental, the random to organic form and order is to commit collective suicide; and by the same token, to create a counter-movement to the irrationalities and threatened exterminations of our day, we must draw close once more to the healing order of nature, modified by human design. Lewis Mumford "Landscape and Townscape" in The Urban Prospect (New York, 1968) The American Adam has been forced, in the twentieth century, to change in time, to recognize the inexorable movement of history which, in his original conception, he was intended to deny. The national mythology which posited his existence has also threatened in recent decades to become absurd. This mythology, variously called the "myth of the garden" or the "Edenic myth," accepts Hector St. John de Crevecoeur's judgment, formed in the 1780's, that man in the New World of America is as a reborn Adam, innocent, virtuous, who will forever remain free of the evils of European history and civilization. "Nature" —never clearly defined, but understood as the polar opposite of what was perceived as the evil corruption and decadence of civilization in the Old World—was the great New World lap in which this mythic self-concep tion sat, the simplicity of absences which assured the American of his eternal newness. The authors who have examined this mythic complex in recent years have usually resigned themselves to its gradual senescence and demise in the twentieth century. -

ANALYSIS Omoo (1847) Herman Melville (1819-1891) “One Can Revel in Such Richly Good-Natured Style…. We Therefore Recommend T

ANALYSIS Omoo (1847) Herman Melville (1819-1891) “One can revel in such richly good-natured style…. We therefore recommend this ‘narrative of adventure in the south seas’ as thorough entertainment—not so light as to be tossed aside for its flippancy, nor so profound as to be tiresome.” Walt Whitman Brooklyn Daily Eagle (5 May 1847) “Omoo is a fascinating book: picaresque, rascally, roving. Melville as a bit of a beachcomber. The crazy ship Julia sails to Tahiti, and the mutinous crew are put ashore. Put in the Tahitian prison. It is good reading. Perhaps Melville is at his best, his happiest, in Omoo. For once he is really reckless…. For once he is really careless, roving with that scamp, Doctor Long Ghost. For once he is careless of his actions, careless of his morals, careless of his ideals: ironic, as the epicurean must be…. But it was under the influence of the Long Doctor. This long and bony Scotsman was not a mere ne’er-do-well. He was a man of humorous desperation, throwing his life ironically away…. He let his ship drift rudderless…. When he saw a white man really ‘gone savage,’ a white man with a blue shark tattooed over his brow, gone over to the savages, then Herman’s whole being revolted. He couldn’t bear it.” D. H. Lawrence Studies in Classic American Literature (1923; Doubleday 1953) “The play of fantasy in Omoo takes the form not of nightmarishness or even of daydreaming but of an easy and emotionally liberating current of humorous narrative, always slightly in excess, as one sees with half an eye, of the sober autobiographical facts. -

A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”

Washington University Law Review Volume 1962 Issue 3 Symposium: The City in History by Lewis Mumford 1962 A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History” Daniel R. Mandelker Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Land Use Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Mandelker, A Review of Lewis Mumford, “The City in History”, 1962 WASH. U. L. Q. 299 (1962). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol1962/iss3/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVIEW OF LEWIS MUMFORD, 'THE CITY IN HISTORY' DANIEL R. MANDELKER* INTRODUCTION What can a lawyer expect from a book of this kind? As a wide- ranging document of social history, it deals expansively with the form and function of the city in western civilization, from ancient times down to the present. Although Mumford is concerned in the larger sense with the city as a citadel of law and order, he is not concerned in the narrower sense with the legal structure that lies behind planning and other municipal functions. Nevertheless, the book has great value to the lawyer for the perspective it can give him. The book is diffuse. Mumford's major themes do not stand forth clearly, his preferences are merely implicit in what he says, and he certainly offers no cure-all for the ills which he sees as besetting the modern metropolis. -

Noc19 Ar05 Assignment12

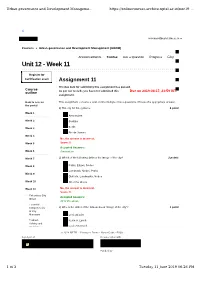

Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_... X [email protected] ▼ Courses » Urban governance and Development Management (UGDM) Announcements Course Ask a Question Progress FAQ Unit 12 - Week 11 Register for Certification exam Assignment 11 The due date for submitting this assignment has passed. Course As per our records you have not submitted this Due on 2019-04-17, 23:59 IST. outline assignment. How to access This assignment contains a total of nine multiple choice questions. Choose the appropriate answer. the portal 1) The city for the cyclist is: 1 point Week 1 Amsterdam Week 2 Curitiba Berlin Week 3 Rio de Janeiro Week 4 No, the answer is incorrect. Week 5 Score: 0 Accepted Answers: Week 6 Amsterdam Week 7 2) Which of the following defines the image of the city? 2 points Week 8 Paths, Edges, Nodes Landmark, Nodes, Paths Week 9 Districts, Landmarks, Nodes Week 10 All of the above Week 11 No, the answer is incorrect. Score: 0 Enhancing City Accepted Answers: Image All of the above Essential Competencies 3) Who is the writer of the famous book “Image of the city”? 1 point of City Managers Le Corbusier Problem Kevin A. Lynch Solving and Decision Lewis Mumford Making © 2014Jan NPTEL Gehl - Privacy & Terms - Honor Code - FAQs - Effective A project of No, the answer is incorrect. In association with Negotiation Score: 0 Communication Accepted Answers: Skills Kevin A. Lynch Funded by Quiz : 1 of 3 Tuesday 11 June 2019 06:26 PM Urban governance and Development Manageme... https://onlinecourses-archive.nptel.ac.in/noc19_.. -

Final Final Kromer

______________________________________________________________________________ CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VACANT-PROPERTY POLICY AND PRACTICE: BALTIMORE AND PHILADELPHIA John Kromer Fels Institute of Government University of Pennsylvania A Discussion Paper Prepared for The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy and CEOs for Cities October 2002 ______________________________________________________________________ THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER ON URBAN AND METROPOLITAN POLICY SUMMARY OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS * DISCUSSION PAPERS/RESEARCH BRIEFS 2002 Calling 211: Enhancing the Washington Region’s Safety Net After 9/11 Holding the Line: Urban Containment in the United States Beyond Merger: A Competitive Vision for the Regional City of Louisville The Importance of Place in Welfare Reform: Common Challenges for Central Cities and Remote Rural Areas Banking on Technology: Expanding Financial Markets and Economic Opportunity Transportation Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality Signs of Life: The Growth of the Biotechnology Centers in the U.S. Transitional Jobs: A Next Step in Welfare to Work Policy Valuing America’s First Suburbs: A Policy Agenda for Older Suburbs in the Midwest Open Space Protection: Conservation Meets Growth Management Housing Strategies to Strengthen Welfare Policy and Support Working Families Creating a Scorecard for the CRA Service Test: Strengthening Banking Services Under the Community Reinvestment Act The Link Between Growth Management and Housing