Willie Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School Certificate for Approving The

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Susan Pelle Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________ Director Dr. Stefanie Kyle Dunning _____________________________________ Reader Dr. Madelyn M. Detloff _____________________________________ Reader Dr. Kathleen N. Johnson _____________________________________ Graduate School Representative Dr. Emily A. Zakin ABSTRACT (DIS)ARTICULATING BODIES AND GENDERS: PUSSY POLITICS AND PERFORMING VAGINAS by Susan Pelle The vagina has metaphorically and metonymically been the body part that stands in for the category “woman” and it is this emphatic and fabricated link that imposes itself on bodies, psyches, and lives with often horrifying consequences. My goals in exploring performative and performing vaginas are many. I not only lay out how, why, and in what ways the “normal” and “abled” female body established in both dominant and mainstream discourses is, simply put, one with a specific type of vagina, but I also confront the “truth” that vaginas purport to tell about women and femininity. Ultimately, I maintain that representations of vaginas and the debates and discourses that surround them tell us something about our culture’s fears, anxieties, and hopes. Living life as abject can be painful, even unbearable, yet as individuals negotiate this life they can experience pleasure, assert agency, and express ethical and just visions of the world. The artists, writers, and performers explored in this dissertation strategically perform vaginas in multiple and disparate ways. As they trouble, resist, and negotiate “normative” understandings of vaginas, they simultaneously declare that the “problem” is not about bodies at all. The problem is not the vagina. -

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

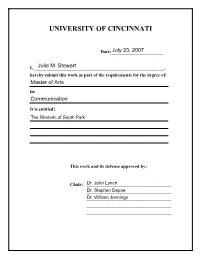

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Stream South Park Online Free No Download Stream South Park Online Free No Download

stream south park online free no download Stream south park online free no download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbdf08ddb7c40b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Stream south park online free no download. Watch full episodes of your favorite shows with the Comedy Central app.. Enjoy South Park, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Broad City and many more, . New episodes of “South Park” will now go through many windows — on television on Comedy Central, on the web at SouthParkStudios for . How to watch South Park on South Park Studios: · Go to: http://southpark.cc.com/.. · Select “Full episodes” from the top menu.. south park episodes. South Park Zone South Park Season 23.. Watch all South Park episodes from Season 23 online . "Mexican Joker" is the first episode of the twenty-third season of . seasons from many popular shows exclusively streaming on Hulu including Seinfeld, Fargo, South Park and Fear the Walking Dead. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

Karaoke by Keysdan Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird'

Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Addicted To Spuds 'Weird' Al Yankovic Alimony 'Weird' Al Yankovic Amish Paradise 'Weird' Al Yankovic Another Rides The Bus 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Eat It 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ebay 'Weird' Al Yankovic Fat 'Weird' Al Yankovic Grapefruit Diet 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Lost On Jeopardy 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Love Rocky Road 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Want A New Duck 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic My Bologna 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Phony Calls 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ricky 'Weird' Al Yankovic Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic She Drives Like Crazy 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Spam 'Weird' Al Yankovic The Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic Yoda 'Weird' Al Yankovic You Don't Love Me Anymore 2 Live Crew Me So Horny Adam Sandler At A Medium Pace (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Adam Sandler Ode To My Car (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Piece Of S--t Car Adam Sandler What The H--- Happened To Me Adam Sandler What The Hell Happened To Me www.KeysDAN.com 501.470.6386 Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Bill Clinton Parody Bimbo No.5 Britney Spears Parody Oops I Farted Again CLEDUS T JUDD MY CELLMATE THINKS I'M SEXY Cheech & Chong Earache My Eye Chef Chocolate Salty Balls Chef Love Gravy Chef No Substitute, Oh Kathy Lee Chef Simultaneous Chef & Meatloaf Tonight Is Right for Love Chef & No Substitute Oh Kathy Lee Chef (South Park) Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

'South Park' 'Imaginationland' Mobile Game

COMEDY CENTRAL® and RealNetworks® Announce the Worldwide Launch of 'South Park' 'Imaginationland' Mobile Game Mobile Game Based On The Hugely Popular "South Park" "Imaginationland" Trilogy To Launch Worldwide In June LAS VEGAS - April 1, 2008 - COMEDY CENTRAL Mobile, a division of MTVN Entertainment Group, a unit of Viacom (NYSE: VIA, VIA.B) and RealArcade Mobile®, a division of digital entertainment services company RealNetworks® Inc. (NASDAQ: RNWK) focused on mobile casual gaming, announced today the launch of the new "South Park" "Imaginationland" mobile game. Based on COMEDY CENTRAL's hugely popular "South Park" "Imaginationland" trilogy, in which the doors of the world's imagination are thrown wide open and the boys of South Park are transported to a magical realm in their greatest odyssey ever. The mobile game will be available cross carrier and on a variety of handsets including the Apple® iPhone™, and various Windows Mobile and Blackberry mobile devices. COMEDY CENTRAL Mobile and RealArcade Mobile plan to release the "South Park" "Imaginationland" game worldwide in June. The player's mission in the "South Park" "Imaginationland" mobile game is to take on Butters' massive job to rescue the world in three arenas (Happy Imaginationland, Evil Imaginationland and The Battle for Imaginationland). The quest begins with the Mayor teaching the player how to bounce high by using his imagination. The player must utilize his bouncing skills to collect items and accomplish missions inside an allotted time limit. As the player accomplishes more missions, Butters gains extra imagination power to restore Imaginationland from the grasp of evil. "South Park" "Imaginationland" mobile game has more than 60 mind-blowing levels. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation.