Technical Report for More Details on the Definition of Direct and Indirect Impacts1 and the Study Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clovis Municipal Airport

Clovis Municipal Airport BAirportigBear MasterCityAi Planrport Master Plan Planning Services BigBearCityAirport Master Plan Planning Services Prepared by: In association with AIRPORT MASTER PLAN for Clovis Municipal Airport Clovis, New Mexico Prepared for City of Clovis, New Mexico by KSA, Inc. in association with CDM Smith, Inc. DRAFT FINAL September 2015 The preparation of this document was financially support, in part, through a grant provided by the New Mexico Department of Transportation. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the NMDOT or Federal Aviation Administration. Acceptance of this report by the NMDOT or FAA does not in any way constitute a commitment on the part of the State of New Mexico or United States to participate in any development depicted therein nor does it indicate that the proposed development is environmentally acceptable or would have justification in accordance with appropriate public laws. PLAN Table of Contents Chapter One: Inventory of Existing Conditions 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Overview of the Airport .......................................................................... 1-2 1.2.1 CVN Location .................................................................................1-2 1.2.2 CVN Sponsor Management ..............................................................1-4 1.2.3 CVN History ....................................................................................1-5 -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 61 | Issue 4 Article 2 1996 Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne, Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization, 61 J. Air L. & Com. 793 (1996) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol61/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WOULD COMPETITION IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION EVER FIT INTO THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION? RUWANTISSA I.R. ABEYRATNE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 794 II. THE GENESIS OF AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS ......... 795 A. TiH CHICAGO CONFERENCE ...................... 795 B. THE CHICAGO CONVENTION ..................... 800 C. POST-CHICAGO CONVENTION TRENDS ............ 802 D. THiE BERMUDA AGREEMENT ...................... 805 E. Ti ROLE OF ICAO ............................. 808 III. RECENT TRENDS .................................. 809 A. THE AI TRANSPORT COLLOQUIUM .............. 809 B. POST-COLLOQUIuM TRENDS ...................... 811 C. THE WORLD-WIDE AIR TRANSPORT CONFERENCE. 814 D. SOME INTERIM GLOBAL ISSUES ................... 816 E. OBJECTWES OF THE CONFERENCE ................ 819 F. EXAMINATION OF ISSUES -

2004 Annual Report on Aviation

NEW YORK STATE ANNUAL REPORT ON AVIATION Includes Legislative Mandates for: Inventory of General Aviation Facilities and Status Report for the Airport Improvement and Revitalization Program (AIR 99) February 1, 2004 New York State Department of Transportation Passenger Transportation Division Aviation Services Bureau 50 Wolf Road Albany, NY 12232 GEORGE E. PATAKI JOSEPH H. BOARDMAN GOVERNOR www.dot.state.ny.us COMMISSIONER TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF DATA.............................................................................2 Map of Public Use Airports .................................................................................................3 III. INVENTORY OF AIRPORTS.........................................................................................4 Table A - Number of and Activity at NYS Aviation Facilities by Type .............................4 Table B - Commercial Service Airports by County, Name, Usage, and Class....................5 Table C - General Aviation Airports by County Name, Usage, and Class..........................6 Table D - Public Use Heliports by County, Name, Usage, and Class ...............................10 Table E - Public Use Seaplane Bases by County, Name, Usage, and Class......................11 IV. AIRPORT ACTIVITY AND SERVICE........................................................................12 Findings..............................................................................................................................12 -

15.0 Appendices

15.0 APPENDICES 15.1 APPENDIX A: STATE PERMIT REQUIREMENTS States have varying requirements for summer flounder permits, as summarized below (information as of April 2017). Massachusetts All persons who land and sell finfish in Massachusetts must have a commercial fishing permit from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (MADMF) and must sell only to permitted Massachusetts dealers. A limited entry summer flounder (fluke) permit endorsement, in addition to a Massachusetts commercial fishing permit, is required for any individual and/or vessel to commercially fish for summer flounder within the state waters of Massachusetts, or to harvest, process, or land any summer flounder for commercial purposes in Massachusetts. This endorsement is limited entry due to a moratorium on new fluke endorsements instated in 1999 to address a substantial increase in participation and landings. The fluke endorsement must be renewed annually. MADMF policy has largely been against transfer of summer flounder endorsements, in order to maintain the moratorium’s effectiveness in reducing the total number of endorsements. However, MADMF allows endorsement transfers between immediate family members (provided they meet the existing eligibility criteria) on a one-time basis, after which the endorsement becomes non- transferable. In addition, inshore trawl fishermen who sell their businesses (i.e., vessels, permits, etc.) may transfer a summer flounder endorsement if the other permits are active as inshore trawling could result in excessive summer flounder discards otherwise. For the offshore fishery, transfer of the summer flounder endorsement to the new permit holder is allowed when vessels and federal permits are sold. Rhode Island A Rhode Island (RI) commercial fishing license with a restricted finfish endorsement is required to take summer flounder for commercial purposes from Rhode Island waters. -

A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019

Airbus A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019 Contents Scope and definitions 02 1.0 2020 & beyond 05 Accidents in 2019 07 2020 & beyond 08 Forecast increase in number of aircraft 2019-2038 09 2.0 Commercial aviation accidents since the advent of the jet age 10 Evolution of the number of flights & accidents 12 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 13 Impact of technology on aviation safety 14 Technology has improved aviation safety 16 Evolution of accident rates by aircraft generation 17 3.0 Commercial aviation accidents over the last 20 years 18 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 20 Ten year moving average of accident rate 21 Accidents by flight phase 22 Distribution of accidents by accident category 24 Evolution of the main accident categories 25 Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident rates 26 Loss Of Control In-flight (LOC-I) accident rates 27 Runway Excursion (RE) accident rates 28 List of tables & graphs 29 A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958 / 2019 02 Scope and definitions This publication provides Airbus’ a flight in a commercial aircraft annual analysis of aviation accidents, is a low risk activity. with commentary on the year 2019, Since the goal of any review of aviation as well as a review of the history of accidents is to help the industry Commercial Aviation’s safety record. further enhance safety, an analysis This analysis clearly demonstrates of forecasted aviation macro-trends that our industry has achieved huge is also provided. These highlight key improvements in safety over the factors influencing the industry’s last decades. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

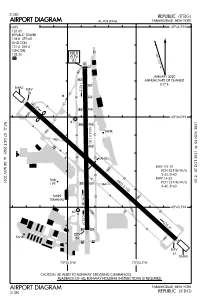

KFRG Procedures

21280 REPUBLIC (FRG) AIRPORT DIAGRAM AL-704 (FAA) FARMINGDALE, NEW YORK ATIS 40°44.5'N 126.65 REPUBLIC TOWER 118.8 279.65 GND CON 121.6 269.6 CLNC DEL Q VA 128.25 FIELD R ELEV D 13 19 . 81 0 ° W G1 1 B JANUARY 2020 B2 ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE 192 G2 0.0° E EMAS . ELEV 2 ° 78 C B G3 14 145 C .2 E ° B3 G4 1 A F 40°44.0'N H C NE-2, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV #1 A B4 G5 5516 2 TANK A G B X 150 A3 G6 N A G B P LAHSO RWY 01-19 2 D PCN 22 F/B/W/U G S-45, D-60 A D RWY 14-32 TWR 6833 PCN 22 F/B/W/U NE-2, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 199 B5 G7 A4 X S-45, D-60 150 0 G . A MAIN 3 1 % D TERMINAL U P A 40°43.5'N H G 5 D H #2 B 8 012 . 2 325 ° .3 A ° B6 G9 1 ELEV TANK 64 6 A M M 32 ELEV 61 EMAS 73°25.0'W 73°24.5'W CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. AIRPORT DIAGRAM FARMINGDALE, NEW YORK 21280 REPUBLIC (FRG) (DEEZZ5.DEEZZ)18200 AL-704 (FAA) REPUBLIC (FRG) DEEZZ FIVE DEPARTURE (RNAV) FARMINGDALE, NEW YORK ATIS 126.65 TOP ALTITUDE: CLNC DEL 3000 128.25 GND CON 121.6 269.6 REPUBLIC TOWER 118.8 279.65 NEW YORK DEP CON 11000 125.7 353.75 *2900 8000 290 ° *2600 15000 KURNL (16) 143 2700 295 * ° ° 230 ° 9 NM HEERO (16 252) ) K (27 DEEZZ 323 CANDR ° TAKEOFF MINIMUMS 15000 ° 2600 009 * ) Rwys 14, 19: Standard. -

March 9, 2021 by ELECTRONIC MAIL

National Air Carrier Association 1735 North Lynn Street, Suite 105 Arlington, VA 22209 T: +1.703.358.8060 March 9, 2021 BY ELECTRONIC MAIL The Honorable Steven M. Dickson Administrator Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, DC 20591 Dear Administrator Dickson, Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Air Carrier Association (NACA) and its member carriers1 have worked closely with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) staff on various operational challenges. One of the more unique issues related to the pandemic has been an increase in disruptive passengers and crewmember assaults, often resulting from disputes associated with mask requirements. In mid-January, in the wake of the insurrection at the United States Capitol Building, the FAA instituted a Special Enforcement Emphasis Program (SEEP) designed to provide a “zero-tolerance”, maximum penalty, for passengers who have caused significant disruptions in-flight, or committed a physical assault against a member of a flight crew while onboard an aircraft. This program is scheduled to end on March 30, 2021. Many in the airline industry thought the SEEP would bring a significant reduction in disruptive passenger incidents. However, since the SEEP’s inception, our Ultra Low- Cost Carriers (ULCCs) 2 have seen little to no decline in the number of daily disruptive passenger incidents. Sufficient time has not been provided for the impact of the program to be known to the traveling public. Without an understanding of the significant penalties associated with the SEEP, passenger behavior has not been altered by the program’s implementation and the risk to the crew has not been mitigated. -

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams Raymond E. King, Psy.D. Major, USAF, BSC Chief, Research Branch HQ Air Force Safety Center Policy, Research, and Technology Division ABSTRACT Commission and the NCARC both The number of commercial airplanes in service recommended that, to find a way to reduce will nearly double by the year 2015, going from aviation accidents, the FAA work with the airline about 12,000 airplanes today to over 23,000 in industry to establish some form of strategic 2015. On a worldwide basis, the data suggest safety plan. nearly a hull loss accident per week by the year 2015 at the current accident rate, which has In 1997, at an NCARC hearing, FAA and airline plateaued over the last decade. Many ideas for industry representatives testified about how they enhancing safety focus on technology were investigating the root causes of aviation improvements to airplanes. While such accidents. The FAA Deputy Director of Aircraft improvements are important, it should be noted Certification Service, Beth Erickson, testified for that their impact would not be significant unless the agency: "We had learned from past efforts they can be implemented on the existing airplane that safety improvements were better fleet. A large portion of the airplanes that will be accomplished when we worked with competent operating in 2007 have already been built, and aviation authorities--pilot unions, airlines, most of the rest have already been designed. The aircraft and aerospace manufacturers, and so data show there are significant factors outside of forth--all pooling our expertise to come up with the airplane design itself that influence the the best way to deal with safety issues. -

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2

DCCD Doc No. 28 28/4/09 (English only) INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AIR LAW (Montréal, 20 April to 2 May 2009) CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE CAUSED BY AIRCRAFT TO THIRD PARTIES AND CONVENTION ON COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGE TO THIRD PARTIES, RESULTING FROM ACTS OF UNLAWFUL INTERFERENCE INVOLVING AIRCRAFT (Presented by the Air Crash Victims Families Group) 1. INTRODUCTION – SUPPLEMENTAL AND OTHER COMPENSATIONS 1.1 The apocalyptic terrorist attack by the means of four hi-jacked planes committed against the World Trade Center in New York, NY , the Pentagon in Arlington, VA and the aborted flight ending in a crash in the rural area in Shankville, PA ON September 11th, 2001 is the only real time example that triggered this proposed Convention on Compensation for Damage to Third Parties from Acts of Unlawful Interference Involving Aircraft. 1.2 It is therefore important to look towards the post incident resolution of this tragedy in order to adequately and pro actively complete ONE new General Risk Convention (including compensation for ALL catastrophic damages) for the twenty first century. 2. DISCUSSION 2.1 Immediately after September 11th, 2001 – the Government and Congress met with all affected and interested parties resulting in the “Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act” (Public Law 107-42-Sept. 22,2001). 2.2 This Law provided the basis for Rules and Regulations for: a) Airline Stabilization; b) Aviation Insurance; c) Tax Provisions; d) Victims Compensation; and e) Air Transportation Safety. DCCD Doc No. 28 - 2 - 2.3 The Airline Stabilization Act created the legislative vehicle needed to reimburse the air transport industry for their losses of income as a result of the flight interruption due to the 911 attack. -

TWA's Lockheed Constellation Makes Trip To

www.MetroAirportNews.com Serving the Airport Workforce and Local Communities November 2018 INSIDE THIS ISSUE TWA’s Lockheed Constellation Makes Trip to JFK Airport – On I-95 A vintage commercial airplane embarked on a long, slow journey from Maine to New York where it will be turned into a cocktail lounge. The long trip of the Lockheed Constellation, known as the “Connie,” kicked off Monday, Oc- Tyler Moss, TWA Hotel CEO went to Maine to supervise the reinstallation of the Connie 04 tober 7th at a send-off event Auburn-Lewiston Airport in Maine. The plane then departed JFK To Get Two New Terminals Tuesday morning and make its way over the next several days to New York on a tow truck. Decorated in authentic TWA livery, our Connie — whose fleet once served as Air Force One for President Dwight D. Eisenhower and broke the record for fastest nonstop trip from Burbank to New York with former TWA owner Howard Hughes at the helm in 1946 — deserves a victory lap before welcoming hotel guests into her cockpit. So, as with all things related to the TWA Hotel project, we looked to TWA’s rich history for inspiration. 15 Continued on page 3 JetBlue Teams Up With the Brooklyn Nets for Its Newest Special Livery EWR Celebrates Past, Present and Future With Ceremonial Groundbreaking Newark Airport which opened on October 1, 1928, was known as the first major airport in the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area. Newark was the first airport in the country with paved runways and an air traffic control 30 tower, and the second with a terminal building.