Is Life the Ultimate Value? a Reassessment of Ayn Rand's Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Ayn

Who Is Ayn Rand? Ayn Rand Few 20th century intellectuals have been as influential—and controversial— as the novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand. Her thinking still has a profound impact, particularly on those who come to it through her novels, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead—with their core messages of individualism, self-worth, and the right to live without the impositions of others. Although ignored or scorned by some academics, traditionalists, pro- gressives, and public intellectuals, her thought remains a major influence on Ayn Rand many of the world’s leading legislators, policy advisers, economists, entre- preneurs, and investors. INTRODUCTION AN Why does Rand’s work remain so influential? Ayn Rand: An Introduction illuminates Rand’s importance, detailing her understanding of reality and human nature, and explores the ongoing fascination with and debates about her conclusions on knowledge, morality, politics, economics, government, AN INTRODUCTION public issues, aesthetics and literature. The book also places these in the context of her life and times, showing how revolutionary they were, and how they have influenced and continue to impact public policy debates. EAMONN BUTLER is director of the Adam Smith Institute, a leading think tank in the UK. He holds degrees in economics and psychology, a PhD in philosophy, and an honorary DLitt. A former winner of the Freedom Medal of Freedom’s Foundation at Valley Forge and the UK National Free Enterprise Award, Eamonn is currently secretary of the Mont Pelerin Society. Butler is the author of many books, including introductions on the pioneering economists Eamonn Butler Adam Smith, Milton Friedman, F. -

Introducing More Students to Ayn Rand's Ideas

Volume 11, Number 9, September 2005 Introducing More Students to Ayn Rand’s Ideas he 14,332 high school students who entered Ayn Rand’s works but, for lack of funding, cannot Tthe Ayn Rand Institute’s annual essay contest obtain enough copies for their classrooms. With in 2005 will soon receive an acknowledgement of the books, we also send suggested lesson-plans their effort and an invitation to read another of Ayn and teachers guides. Rand’s novels—in the form of a free copy of The In the last three years the Institute has distrib- Fountainhead or Atlas Shrugged. uted more than 165,000 free books. Whereas, to In the fall ARI will send all students who date, the flyers have produced a steadily grow- submitted essays to The Fountainhead contest ing stream of book requests, the Web site has the last academic year a complimentary copy of potential to generate a torrent. Atlas Shrugged. These students are entering their ARI’s ability to supply books depends senior year in school or have recently graduated; on funding. The decision to invite teachers to those starting college are eligible to enter our request books online was made after the Institute contest on Atlas. received a million-dollar contribution to help All 9,525 students who entered the Anthem fund the program. contest as freshmen or sophomores in 2005 will soon receive a copy of The Fountainhead. Of these Foundation’s Grant Is Matched—Again former entrants, students now in the 11th grade are For the second straight year, a foundation in eligible to enter the Fountainhead contest. -

Understanding Rational Egoism

Understanding Rational Egoism CRAIG BIDDLE Copyright © 2018 by The Objective Standard. All rights reserved. The Rational Alternative to “Liberalism” and Conservatism OBAMACARE v. GOVERNMENT’S ASSAULT ANDY KESSLER ON Ayn Rand THE BRILLIANCE THE CONSTITUTION (p.11) ON CAREER COLLEGES (p.53) “EATING PEOPLE” (p.75) Contra Nietzsche CEO Jim Brown’s Vision OF LOUIS PASTEURTHE OBJECTIVE STANDARD THE WAR BETWEEN STANDARD OBJECTIVE THE for the Ayn Rand Institute EDUCATION IN INTELLECTUALS AND CAPITALISM Capitalism A FREE SOCIETY Because Science Alex Epstein on How to The Objective StandardVOL. 6, NO. 2 • SUMMER 2011 THE OBJECTIVE STANDARD The Objective Standard Improve Your World – 2014 VOL. 8, NO. 4 • WINTER 2013 Robin Field on Objectivism Forand theProfit Performing Arts The Objective Standard VOL. 12, NO. 1 • SPRING 2017 “Ayn Rand Said” Libertarianism It is Is Not an Argument VOL. 11, NO. 2 • SUMMER 2016 vs. THE OBJECTIVE STANDARD Time: The Objective Standard Radical Capitalism America CONSERVATIVES’FAULT at Her The Iranian & Saudi Regimes Best Plus: Is SPRING 2017 ∙ VOL. 12, NO. 1 NO. 12, VOL. ∙ 2017 SPRING (p.19) SUMMER 2011 ∙ VOL. 6, NO. 2 NO. 6, ∙ VOL. SUMMER 2011 MUST GO WINTER 2013–2014 ∙ VOL. 8, NO. 4 Plus: Ex-CIA Spy Reza Kahlili on Iran’s Evil Regime (p.24)Hamiltonian Ribbon, Orange Crate, and Votive Holder, 14” x 18” Historian John D. Lewis on U.S. Foreign Policy (p.38) LINDA MANN Still Lifes in Oil SUMMER 2016 ∙ VOL. 11, NO. 2 lindamann.com ∙ 425.644.9952 WWW.CAPITALISTPIG.COM POB 1658 Chicago, IL 60658 An actively managed hedge fund. -

200306 IMPACT02.Qxd

Volume 9, Number 6, June 2003 Local Activism: Introducing Ayn Rand’s In the Media: Dr. Brook on PBS In May 2002 Dr. Yaron Brook was a panelist on Books Into Texas Schools The McCuistion Program; the topic was “The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Solutions for Peace.” That program re-aired last month, at various The Houston Objectivism Society (HOS), an At one school she suggested that her times, on PBS and cable channels throughout independent community group that promotes the department obtain copies of Anthem and Ayn the country. study of Ayn Rand’s philosophy, has long Rand’s play Night of January 16th. As a result, supported ARI’s projects. For several years a fellow teacher is using them in class, “because . and on Fox News Channel HOS has amplified the effect of our high school she saw them on the shelves, and she remem- On April 27 Dr. Brook was interviewed on the essay contest on Anthem and The Fountainhead bered me telling her how much my students Fox News Channel show At Large With by sponsoring prizes for contest winners in the enjoyed the books,” said Ms. Wich. Geraldo. He discussed the dangers of an Houston area. Since 1995 the members of HOS Iranian-backed attempt to install an Islamic have given more than $18,000 in scholarship Books Quickly Win Fans Among Students theocracy in post-war Iraq. money to local winners. The overwhelming response to Though the efforts of HOS Anthem and The Fountainhead, . and on C-SPAN have helped to encourage teachers she continued, “was extremely In April Dr. -

The American Philosophical Association EASTERN DIVISION ONE HUNDRED TENTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM

The American Philosophical Association EASTERN DIVISION ONE HUNDRED TENTH ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM BALTIMORE MARRIOTT WATERFRONT BALTIMORE, MARYLAND DECEMBER 27 – 30, 2013 Important Notices for Meeting Attendees SESSION LOCATIONS Please note: the locations of all individual sessions will be included in the paper program that you will receive when you pick up your registration materials at the meeting. To save on printing costs, the program will be available only online prior to the meeting; with the exception of plenary sessions, the online version does not include session locations. In addition, locations for sessions on the first evening (December 27) will be posted in the registration area. IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT REGISTRATION Please note: it costs $40 less to register in advance than to register at the meeting. The advance registration rates are the same as last year, but the additional cost of registering at the meeting has increased. Online advance registration at www.apaonline.org is available until December 26. 1 Friday Evening, December 27: 6:30–9:30 p.m. FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING 1:00–6:00 p.m. REGISTRATION 3:00–10:00 p.m., registration desk (third floor) PLACEMENT INFORMATION Interviewers and candidates: 3:00–10:00 p.m., Dover A and B (third floor) Interview tables: Harborside Ballroom, Salons A, B, and C (fourth floor) FRIDAY EVENING, 6:30–9:30 P.M. MAIN PROGRAM SESSIONS I-A. Symposium: Ancient and Medieval Philosophy of Language THIS SESSION HAS BEEN CANCELLED. I-B. Symposium: German Idealism: Recent Revivals and Contemporary Relevance Chair: Jamie Lindsay (City University of New York–Graduate Center) Speakers: Robert Brandom (University of Pittsburgh) Axel Honneth (Columbia University) Commentator: Sally Sedgwick (University of Illinois–Chicago) I-C. -

ARI Co-Hosts Third Conference for BB&T Professors

Volume 14, Number 6, June 2008 A Message from ARI Co-Hosts Third Conference for John P. McCaskey BB&T Professors professor who wants to include Atlas AShrugged in his classes faces many chal- lenging questions, from “How do I teach the novel?” to “How do I get students to read such John P. McCaskey, PhD, is a long book in the first place?” For participants the founder and chairman in the BB&T Charitable Foundation-sponsored of the board of the Anthem programs for the study of capitalism, those Foundation for Objectivist questions—and many others—are addressed at Scholarship, as well as an the annual conference for BB&T professors co- Dr. John McCaskey ARI board member. The hosted by ARI and the Clemson Institute for the Left to right: Drs. Onkar Ghate, Tara Smith, Yaron Brook, Anthem Foundation is a Study of Capitalism in Clemson, South Carolina. C. Bradley Thompson 501(c)(3) organization, separate from ARI, that This year marked the third such confer- provides funding to colleges and universities for ence, which drew thirty-one attendees, including Yaron Brook lectured on Ayn Rand’s unique teaching, writing or research on Objectivism. eleven first-time attendees. defense of capitalism. For returning attendees, “These conferences give us a chance to Brook and Ghate were joined by two econo- Dear Impact readers, meet and interact with the BB&T-funded pro- mists for a roundtable discussion of economics I am excited to tell you about big organizational, fessors,” said Debi Ghate, ARI’s vice president and morality. operational, and managerial changes we are of Academic programs. -

Ayn Rand Through a Biblical Lens by David S

CHECK YOUR PREMISES: AYN RAND THROUGH A BIBLICAL LENS BY DAVID S. KOTTER. Foreword by Art Lindsley, Ph.D. Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand has been ranked as second only to the Bible as one of the most influential books in the lives of modern readers, and more than 30 million copies of her books have been sold. Nearly a million dollars in cash prizes have been awarded in essay contests encouraging high school and college students to read Rand’s novels, and increasingly universities are making her books required reading. Aside from Rand’s success, why would the Institute for Faith, Work & Economics (IFWE) show interest in reviewing the thoughts behind her works, given that she was a virulent atheist, despised Christianity along with the Bible, condemned any form of altruism, exalted selfishness, and used the dollar bill as her symbol? First, even if you have no intention of reading Rand – and her works are certainly not for everyone – it is at least worth knowing what she believed and how her beliefs compare and contrast with the Bible. Second, any work that appeals to so many people likely contains some truths worth investigating. For example, I have learned specific truths through reading atheist, New Age, and neo-pagan works, even though I reject their overarching worldview. We at IFWE believe in common grace, which means that every favor of whatever kind that this undeserving world enjoys originates from the hand of God. While it is true that unbelievers eventually twist truth, they nonetheless have some truth to twist. In other words, non-believers have both honey – created truth – and hemlock – truth twisted by the Fall. -

Highlights of the Past Year

aynrand.org/impact Volume 17, Number 12, December 2011 Highlights of the Past Year RI’s mission is to foster a growing awareness, paign this fall, we received more orders for free A understanding and acceptance of Ayn Rand’s books in the first month of this academic year revolutionary philosophy of Objectivism, in order than in the same period over the last few years. to create a culture whose guiding principles are As a result, ARI projects it will be out of reason, rational self-interest and laissez-faire books for distribution by the end of this month. If capitalism—a culture in which individuals are free you would like to contribute to the Free Books to to pursue their own happiness. All of ARI’s activi- Teachers program so more high school students ties are geared towards achieving this end. are exposed to Ayn Rand’s ideas in the class- OAC instructor Keith Lockitch (at right) discussing environmentalism with Our efforts are focused on impacting three main room, please visit aynrand.org/freebooks to learn this year’s interns areas in the culture, those targets that, if impacted more about the program and how you can make a internship program for college students new to effectively, will most directly and widely change difference. Rand’s ideas but who are planning to pursue intel- the culture as a whole. These areas of focus are the Another effort to educate young people about lectual careers at its offices in Irvine, California. education system, which includes students and aca- Ayn Rand’s ideas includes ARI’s annual essay This year’s class, our largest yet, consisted of nine- demics; public policy, which includes think tanks, contests, most of which are held exclusively for teen students eager to learn about Rand’s scholar- politicians and activists; and business, the field that high school and college students. -

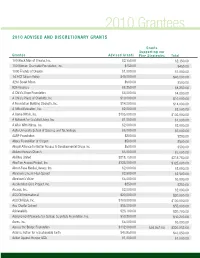

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

The Unlikeliest Cult in History

SKEPTICAL PERSPECTIVES The Unlikeliest Cult in History How even reason, skeptics' most powerful tool, can become the basis of a cult. By Michael Shermer Freudian projection is the process of considered the unlikeliest cult in his op what could, with hindsight, be attributing one's own ideas, feelings, tory. It is a lesson in what happens called a "cult following." The initial or attitudes to other people or when the truth becomes more print-run of 7,500 copies was fol objects-the guilt-laden adulterer important than the search for truth, lowed by multiples of five and 10,000 accuses his spouse of adultery, the when final results of inquiry become until by 1950 half a million copies homophobe actually harbors latent more important than the process of were circulating the country. The homosexual tendencies. A subtle inquiry, and especially when reason book was The Fountainhead and the form of projection can be seen in the leads to an absolute certainty about author Ayn Rand. Her commercial accusation by Christians that secular one's beliefs such that those who are success allowed her the time and humanism and evolution are "reli not for the group are against it. freedom to write her magnum opus, gions;" or by cultists and paranor The story begins in 1943 when an Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957 malists that skeptics are themselves a obscure Russian immigrant pub after ten years in the making. It is a cult and that reason and science have lished her first successful novel after murder mystery, not about the mur cultic properties. -

Arra™ General Session Lectures Ayn (See Pages 4-5) Rand Institute Optional Courses (See Pages 6- 9) ~- ·

~ ~ OCON TT.I June 30 through July 8, 2006 Seaport Hotel Boston, Massachusetts ARra™ General Session Lectures Ayn (see pages 4-5) Rand Institute Optional Courses (see pages 6- 9) ~- ·-. -'r ► YOU ARE INVITED! · t f ,....., rence Hotel Dear Reader: I am pleased to introduce our conference catalog for Objectivist Summer Conference 2006-a nine-day gathering offe1ing leisure, fu n and intellectual vigor that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. We believe that Boston's Seaport Hotel is one of our best conference venues yet; we' re sure that you'll find the accommodations and meeting spaces comfortable and enjoyable. The surrounding downtown area offers a splendid selection of fine dining, shopping and historical landmarks, which 1vill add special significance to your Independence Day holiday. The Boston I Seaport Hotel is But the real attraction of the conference is, of course, our lineup of speakers and courses. Attendees are still an award-winning talking about last summer's offerings, and we are confident that this summer's courses will only add to the deluxe, full-service Objectivist summer conference legacy. Speakers include Objectivist luminaries such as Harry Binswanger, hotel, meeting and John Ridpath, Peter Schwartz and Mary Ann Sures, and topics range from ethics to education, art to opera, exhibition center. politics to perception, and from the ancient Greeks to the corruption of 20th-century philosophy. There are nine general session lectures and sixteen optional courses to choose from, as well as a variety of special Located near events and dinners. Attendees may register for the entire nine-day conference, or use our al a carte registra the Faneuil Hall tion options to choose those parts that best fit your schedule and budget. -

The, Ayi\ Rand Institute

THE,AYI\ RAND INSTITUTE f,l/ewsletter- Vol. 6, No. 1 o The Center for the Advancement of Objectivism o Februarv 1991 Fund-raisingGala Institute in Review Sef for September Unexpected successesand dramatic Library (NAL) last April, over 900 The Ayn Rand Institute is pleased to opporhrnities to reach new audiences professional philosophers-far more announce 'An Evening of Celebration," mark the Ayn Rand Institute's projects than expected-have requested and re- to take place September 28, 1991, at the over the past year. ceived complimentary copies from ARI. Vista Lrternational Hotel in New York As ARI begins its seventh year of In addition, 1990saw the publication by City. This special evening, the third of its operation, its two major projects aimed ARI Press of The Biological Basb of Tele- kind since ARI was established in 1985, at reaching high-school and college ological Concepts, Harry Binswanger's will include a banquet and fund-raising students are flourishing. The Institute work in philosophy of science. A major auction of items from Avn Rand's estate. continues to provide camPus Objectivist project for ARI in 1991 and 19P2will be Following dinner, jo(n Ridpath will clubs with valuable materials and sup- the promotion to the academic commun- preside over the auction of various port (for details on the club project, see ity of Leonard Peikoff's definitive book manuscripts, books, and memorabilia- page three of this newsletter). And 1990 on Ayn Rand's philosophy, Objectiaism: in all, twenty-seven items created, was the best year yet for the Fountainhead ThePhilosophy of Ayn Rand,scheduled for purchased, or collected by Ayn Rand.