With Explanatory Notes and a Glossary. to Which Are Prefixed Some

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Popular British Ballads : Ancient and Modern

11 3 A! LA ' ! I I VICTORIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SHELF NUMBER V STUDIA IN / SOURCE: The bequest of the late Sir Joseph Flavelle, 1939. Popular British Ballads BRioky Johnson rcuvsrKAceo BY CVBICt COOKe LONDON w J- M. DENT 5" CO. Aldine House 69 Great Eastern Street E.G. PHILADELPHIA w J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY MDCCCXCIV Dedication Life is all sunshine, dear, If you are here : Loss cannot daunt me, sweet, If we may meet. As you have smiled on all my hours of play, Now take the tribute of my working-day. Aug. 3, 1894. eooccoc PAGE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xxvii THE PREFACE /. Melismata : Musical/ Phansies, Fitting the Court, Cittie, and Countrey Humours. London, 1 6 1 i . THE THREE RAVENS [MelisMtata, No. 20.] This ballad has retained its hold on the country people for many centuries, and is still known in some parts. I have received a version from a gentleman in Lincolnshire, which his father (born Dec. 1793) had heard as a boy from an old labouring man, " who could not read and had learnt it from his " fore-elders." Here the " fallow doe has become " a lady full of woe." See also The Tiua Corbies. II. Wit Restored. 1658. LITTLE MUSGRAVE AND LADY BARNARD . \Wit Restored, reprint Facetix, I. 293.] Percy notices that this ballad was quoted in many old plays viz., Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the xi xii -^ Popular British Ballads v. The a Act IV. Burning Pestle, 3 ; Varietie, Comedy, (1649); anc^ Sir William Davenant's The Wits, Act in. Prof. Child also suggests that some stanzas in Beaumont and Fletcher's Bonduca (v. -

CHILD BALLADS TRADITIONAL in the UNITED STATES Edited by Bertrand H

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Music Division -- Recording Laboratory Issued from the Collections of the Archive of Folk Song Long-Playing Record L57 CHILD BALLADS TRADITIONAL IN THE UNITED STATES Edited by Bertrand H. Bronson Preface All the songs on this and the following long-playing record (L58) are members, circulating within recent decades in various parts of the United States, of the classic and authoritative canon of traditional narrative-songs of Eng lish and Scottish growth now universally known as the "Child Ballads," after the great nineteenth-century scholar who first assembled and edited them: Professor Francis James Child of Harvard University. Child had a vast and historic knowledge of balladry, defying barriers of language and ranging familiarly through the centuries. After the most strenuous efforts, prolonged for decades, to recover every record of value, he concluded that only a handful were still traditionally alive. What would have been his delighted amazement to learn -- a fact that has been discovered only in our own century and which is spectacularly demonstrated in the Archive of Folk Song -- is that scores of his chosen ballads are even today being sung in strictly traditional forms, not learned from print, across the length and~breadth of this country, in variants literally innumerable! The aim of the present selection is to display some of the Archive's riches, a representative cross-section from the hundreds of Child variants collected by many interested field workers and now safely garnered in the Library of Congress. References for Study: Professor Child set forth his ballad canon in tne monumental English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Boston, Boughton, Mifflin, l882=r898, 10 parts in 5 volumes; reprinted in 3 volumes, New York, Folklore Press, 1956). -

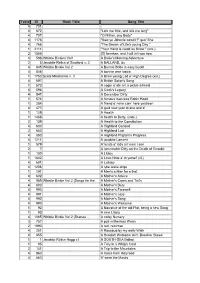

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Tradition Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography

Tradition label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography The Tradition Label was established in New York City in 1956 by Pat Clancy (of the Clancy Brothers) and Diane Hamilton. The label recorded folk and blues music. The label was independent and active from 1956 until about 1961. Kenny Goldstein was the producer for the label during the early years. During 1960 and 1961, Charlie Rothschild took over the business side of the company. Clancy sold the company to Bernard Solomon at Everest Records in 1966. Everest started issuing albums on the label in 1967 and continued until 1974 using recordings from the original Tradition label and Vee Jay/Horizon. Samplers TSP 1 - TraditionFolk Sampler - Various Artists [1957] Birds Courtship - Ed McCurdy/O’Donnell Aboo - Tommy Makem and Clancy Brothers/John Henry - Etta Baker/Hearse Song - Colyn Davies/Rodenos - El Nino De Ronda/Johnny’s Gone to Hilo - Paul Clayton/Dark as a Dungeon - Glenn Yarbrough and Fred Hellerman//Johnny lad - Ewan MacColl/Ha-Na-Ava Ba-Ba-Not - Hillel and Aviva/I Was Born about 10,000 Years Ago - Oscar Brand and Fred Hellerman/Keel Row - Ilsa Cameron/Fairy Boy - Uilleann Pipes, Seamus Ennis/Gambling Suitor - Jean Ritchie and Paul Clayton/Spiritual Trilogy: Oh Freedom, Come and Go with Me, I’m On My Way - Odetta TSP 2 - The Folk Song Tradition - Various Artists [1960] South Australia - A.L. Lloyd And Ewan Maccoll/Lulle Lullay - John Jacob Niles/Whiskey You're The Devil - Liam Clancy And The Clancy Brothers/I Loved A Lass - Ewan MacColl/Carraig Donn - Mary O'Hara/Rosie - Prisoners Of Mississippi State Pen//Sail Away Ladies - Odetta/Ain't No More Cane On This Brazis - Alan Lomax, Collector/Railroad Bill - Mrs. -

Mcalpine (1995)

ýýesi. s ayoS THE GALLOWS AND THE STAKE: A CONSIDERATION OF FACT AND FICTION IN THE SCOTTISH BALLADS FOR MY PARENTS AND IN MEMORY OF NAN ANDERSON, WHO ALMOST SAW THIS COMPLETED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before embarking on the subject of hanging and burning, I would like to linger for a moment on a much more pleasant topic and to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has helped me in the course of my research. Primarily, thanks goes to all my supervisors, most especially to Emily Lyle of the School of Scottish Studies and to Douglas Mack of Stirling, for their support, their willingness to read through what must have seemed like an interminable catalogue of death and destruction, and most of all for their patience. I also extend thanks to Donald Low and Valerie Allen, who supervised the early stages of this study. Three other people whom I would like to take this opportunity to thank are John Morris, Brian Moffat and Stuart Allan. John Morris provided invaluable insight into Scottish printed balladry and I thank him for showing the Roseberry Collection to me, especially'The Last Words of James Mackpherson Murderer'. Brian Moffat, armourer and ordnancer, was a fount of knowledge on Border raiding tactics and historical matters of the Scottish Middle and West Marches and was happy to explain the smallest points of geographic location - for which I am grateful: anyone who has been on the Border moors in less than clement weather will understand. Stuart Allan of the Historic Search Room, General Register House, also deserves thanks for locating various documents and papers for me and for bringing others to my attention: in being 'one step ahead', he reduced my workload as well as his own. -

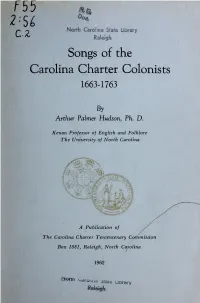

Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists, 1663-1763 Digitized by the Internet Archive

F55 j North Carolina State Library Raleigh Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists 16634763 By Arthur Palmer Hudson, Ph. D. Kenan Professor of English and Folklore The University of North Carolina <-*roma orafe Library Relei§h Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists, 1663-1763 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/songsofcarolinac1962huds Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists 16634763 By Arthur Palmer Hudson, Ph. D. Kenan Professor of English and Folklore The University of North Carolina A Publication of The Carolina Charter Tercentenary Commission Box 1881, Raleigh, North Carolina 1962 ttortft Carolina Sfare Library THE CAROLINA CHARTER TERCENTENARY COMMISSION Hon. Francis E. Winslow, Chairman Henry Belk Mrs. Kauno A. Lehto Mrs. Doris Betts James G. W. MacLamroc Dr. Chalmers G. Davidson Mrs. Harry McMullan Mrs. Everett L. Durham Dr. Paul Murray William C. Fields Dan M. Paul William Carrington Gretter, Jr. Dr. Robert H. Spiro, Jr. Grayson Harding David Stick Mrs. James M. Harper, Jr. J. P. Strother Mrs. Ernest L. Ives Mrs. J. O. Tally, Jr. Dr. Henry W. Jordan Rt. Rev. Thomas H. Wright Ex-Officio Dr. Charles F. Carroll, Robert L. Stallings, Superintendent of Director, Department of Public Instruction Conservation and Developm Dr. Christopher Crittenden, Director, Department of Archives and History Secretary The Carolina Charter Tercentenary Commission was established by the North Carolina General Assembly to "make plans and develop a program for celebration of the tercentenary of the granting of the ." Carolina Charter of 1663 . As part of this program the Com- mission arranged for the publication of a number of historical pamphlets for use in stimulating interest in the study of North Carolina history during the period 1663-1763. -

The Known Words

The Known Words Third Ethereal Edition, A.S. L Revision 4.06, 2017-02-05 Contents and Cross-Reference A Drop Of Nelson's Blood............................80 Don't Let A Landsknecht..............................63 Known World................................................97 A Grazing Mace.............................................95 Drop Of Nelson's Blood, A...........................80 Landlord, Fill The Flowing Bowl..................22 A Lusty Young Smith....................................45 Eve Of Hastings, The....................................46 Last Lochacian Herald, The..........................74 A Pict Song....................................................90 Everybody's Makin' It Big...........................104 Lindisfarne....................................................55 A Sailor's Love Song......................................51 False Knight On The Road, The...................24 Lindisfarne 2.0..............................................55 A Viking Love Song.......................................13 Far Cup, And I, The......................................62 Lion Heart.....................................................92 A Wife's Lament..............................................3 Father, May I Marry?....................................66 Lochac Song, The..........................................28 Ah Poor Bird..................................................36 Feral Privies Song, The.................................39 Lord McGee...................................................72 All I Want Is A Peerage.................................40 -

CHILD BALLADS TRADITIONAL in the UNITED STATES Edited by Bertrand H

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Music Division -- Recording Laboratory FOLK MUSIC OF THE UNITED STATES Issued from the Collections of the Archive of Folk Song Long-Playing Record L58 CHILD BALLADS TRADITIONAL IN THE UNITED STATES Edited by Bertrand H. Bronson Preface All the songs on this and the preceding long-playing record (L57) are members, circulating within recent decades in various parts of the United States, of the classic and authoritative canon of traditional narrative songs of Eng lish and Scottish growth now universally known as the "Child Ballads," after the great nineteenth-century scholar who first assembled and edited them: Professor Francis James Child of Harvard University. Child had a vast and historic knowledge of balladry, defying barriers of language and ranging familiarly through the centuries. After the most strenuous efforts, prolonged for decades, to recover every record of value, he concluded that only a handful were still traditionally alive. What would have been his delighted amazement to learn -- a fact that has been discovered only in our own century and which is spectacularly demonstrated in the Archive of Folk Song -- that scores of his chosen ballads are even today being sung in strictly traditional forms, not learned from print, across the length and breadth of this country, in variants literally innumerable! The aim of the present selection is to display some of the Archive's riches, a representative cross-section from the hundred of Child variants collected by many interested field workers and now safely garnered in the Library of Congress. References for Study: Professor Child set forth his ballad canon in tie monumental English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Boston, Houghton, Mifflin, l882=I898, 10 parts in 5 volumes; reprinted in 3 volumes, New York, Folklore Press, 1956). -

The Child Ballad in Canada: a Survey1

THE CHILD BALLAD IN CANADA: A SURVEY1 LAUREL DOUCETTE and COLIN QUIGLEY While many folklorists might find the tabulation of Child ballad statistics a tedious and somewhat anachronistic exercise, few would deny the historical value of describing in detail the results of one phase of Canadian folksong research. It is our contention, however, that such an exercise serves deeper scholarly concerns. As an examination of a regional classical ballad repertoire, this survey provides a base for comparison with other regions. Given the broad geographic distribution and time depth represented by this genre, the Child ballads are well suited for such comparative study. More over, as the oldest level of the Anglo-Canadian song tradition, the national Child ballad repertoire forms an important base for folk song study within this country. An examination of maintenance and loss of story types within the Child corpus, as well as analysis of transformations undergone by individual ballads, could reveal culturally-specific concerns which may be reflected throughout the entire Canadian folksong repertoire. In addressing this topic, we have very little to go on other than the recorded corpus of material, for most song collections were made before the concept of “context” was introduced to folklore field research. The corpus, however, is substantial, and bears close examination in terms of its composition, distribution, and narrative style. Throughout this paper, when we use the term “ballad,” we mean “Child ballad” ; and we use the titles adopted by Child, followed by the number assigned by him.2 Ballad Research in Canada The earliest record of a British traditional ballad in Canada dates to 1898 when Phillips Barry published a text of “The Gypsy Laddie” (Ch 200) collected in Nova Scotia.3 In 1910 and 1912, W. -

A Collection of Ancient and Modern Scottish Ballads

1 ^.. j5?:--^- ->>> sK; c few ?^- * p^ .^'-l i^' 4.. *\.A^ r. 1, THE GLEN COLLECTION OF SCOTTISH MUSIC Presented by Lady Dorothea Ruggles- Brise to the National Library of Scotland, in memory of her brother. Major Lord George Stewart Murray, Black Watch, killed in action in France in 1914. 28^7/. January 1927. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/collectionofanci01gilc Cj^e.M. s-a A COLLECTION OF ANCIENT AND MODEUN TALES, AND SONGS: WITH EXPLANATORY NOTES AND OBSERVATIONS, BY JOHN GILCHRIST.' IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I. EDINBURGH; PniNTED FOB, WILLIAM BLACKWOOD: AKD BALDWIN, CRADOCK, ^ JOY, PATERKOSTER-BOW^, LONDON. 1815. \^0F SCOTLAND ^] Gilchrist & Heriot, Printers, Leitli. PREFACE. Our relations and intercourse with the sister kingdom have become, from a variety of causes, so intimate, that our manners, our customs, and even our language, are assimilating with rapid strides to those of that country. Not- withstanding, however, that the simple, ex- pressive style of our fathers be becoming less and less frequent in conversation among the middle ranks, yet our poetry is still understood and ad- mired by every Scotchman, and is fondly trea- sured up in the memory of such of our coun- trymen whom adventitious circumstances have placed at a distance from their native land, who pore with delight over the rich humour, tender IV pathos, and descriptive beauty of their country's bards. Our language may fluctuate, and per- haps be lost in the English, but so long as there remains amongst us a taste for simplicity in writ- ing, and beauty in poetry, so long will our an- cient ballads and songs be admired. -

A Checklist of Child Ballad Variants Found in Southern Appalachia

A CHECKLIST OF CHILD BALLAD VARIANTS FOUND IN SOUTHERN APPALACHIA Thomas Burton and Ambrose Manning The following checklist—drawn from a considerable number of major published and unpublished sources, as well as selected minor ones—is a representative inventory of variants of Child ballads found in Southern Appalachia. It does not propose to be a definitive list. Nor does it overcome all the inherent limitations and problems confronting such an inventory; for example the difficulty in delineating “Southern Appalachia” (considered here as basically, but not exclusively, that area prescribed by the Appalachian Regional Commission) and the inability to consult the almost inexhaustible number of sources. We also had to accept such realities as the following: some sources include only one variant of a ballad, whereas other sources include representative variants of all the ones collected; collections sometimes designate, sometimes not, the specific place where a variant was recorded or from whom, but not necessarily where it was learned originally or other critical details of dissemination; some informants are included in multiple collections, and their songs are easily tallied, mistakenly, more than once; duplications can occur through the circumstance of multiple collectors recording from different members of the same family or from different persons who learned the same specific matrix; a collector may include the same variants in multiple collections without specifying whether they have been previously published; the credibility of variants can be dubious relative to a number of factors, including editorial policy; and fragments, summaries, written copies, oral traditional status, authenticity of sources, as well as other matters pose questions that are sometimes unfathomable and ultimately subjective.