Schinus Molle L.) to CONTROL RICE WEEVIL (Sitophilus Oryzae L.

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystems and Agro-Biodiversity Across Small and Large-Scale Maize Production Systems, Feeder Study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”

Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food” i Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge TEEB and the Global Alliance for the Future of Food on supporting this project. We would also like to acknowledge the technical expertise provided by CONABIO´s network of experts outside and inside the institution and the knowledge gained through many years of hard and very robust scientific work of the Mexican research community (and beyond) tightly linked to maize genetic diversity resources. Finally we would specially like to thank the small-scale maize men and women farmers who through time and space have given us the opportunity of benefiting from the biological, genetic and cultural resources they care for. Certification All activities by Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, acting in administrative matters through Nacional Financiera Fideicomiso Fondo para la Biodiversidad (“CONABIO/FFB”) were and are consistent under the Internal Revenue Code Sections 501 (c)(3) and 509(a)(1), (2) or (3). If any lobbying was conducted by CONABIO/FFB (whether or not discussed in this report), CONABIO/FFB complied with the applicable limits of Internal Revenue Code Sections 501(c)(3) and/or 501(h) and 4911. CONABIO/FFB warrants that it is in full compliance with its Grant Agreement with the New venture Fund, dated May 15, 2015, and that, if the grant was subject to any restrictions, all such restrictions were observed. How to cite: CONABIO. 2017. Ecosystems and agro-biodiversity across small and large-scale maize production systems, feeder study to the “TEEB for Agriculture and Food”. -

Life History of Immature Maize Weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on Corn Stored at Constant Temperatures and Relative Humiditi

Popur,erroN Ecor,ocv Life History of Immature Maize Weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)on Corn Storedat Constant Temperaturesand Relative Humidities in the Laboratorv JAMESE. THRONE Sto re d- P ro a" " t I" "L::1, "8llTr%?torv'u s D A-A Rs' ffi fi:Tfr ff#l:t.t ABSTRACTLire historr";itiff*""ii?1",1,"#'*t"tilulitrl f"tit)r", zeamaisMotschursky, was studied at 10-40'C and 4T76Vo RH. The optimal quantity of corn for minimizing density effects and the optimal observation frequency for minimizing disturbance effects were determined at 30'C and 75Vo RH. The quantity of corn (32-256 g) provided to five females ovipositing for 24 h did not affect duration of development, but the number of progeny produced increased asymptotically as the quantity of corn provided increased. Frequency of observation (from l- to l4-d intervals) did not affect duration of development or number of progeny produced. Using moisture contents measured in the life history study, an equation was developed for predicting equilibrium moisture content of corn from temperature and relative humidity. Duration of immature development did not vary with sex, but did vary with test. This suggests that insect strain or chemical composition of the corn must be included as factors in a model predicting effects of environment on duration of immature development. Survival from egg to adult emergence was greatest at 25'C. Sex ratio of emerging adults did not differ from l:1. The number of multiply-infested kernels was low at all environmental conditions, and survival from egg to adult emergence in these kernels averaged L8Vo. -

Effects of Essential Oils from 24 Plant Species on Sitophilus Zeamais Motsch (Coleoptera, Curculionidae)

insects Article Effects of Essential Oils from 24 Plant Species on Sitophilus zeamais Motsch (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) William R. Patiño-Bayona 1, Leidy J. Nagles Galeano 1 , Jenifer J. Bustos Cortes 1 , Wilman A. Delgado Ávila 1, Eddy Herrera Daza 2, Luis E. Cuca Suárez 1, Juliet A. Prieto-Rodríguez 3 and Oscar J. Patiño-Ladino 1,* 1 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Sede Bogotá, Bogotá 111321, Colombia; [email protected] (W.R.P.-B.); [email protected] (L.J.N.G.); [email protected] (J.J.B.C.); [email protected] (W.A.D.Á.); [email protected] (L.E.C.S.) 2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá 110231, Colombia; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá 110231, Colombia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais Motsch) is a major pest in stored grain, responsible for significant economic losses and having a negative impact on food security. Due to the harmful effects of traditional chemical controls, it has become necessary to find new insecticides that are both effective and safe. In this sense, plant-derived products such as essential oils (EOs) appear to be appropriate alternatives. Therefore, laboratory assays were carried out to determine the Citation: Patiño-Bayona, W.R.; chemical compositions, as well as the bioactivities, of various EOs extracted from aromatic plants on Nagles Galeano, L.J.; Bustos Cortes, the maize weevil. The results showed that the tested EOs were toxic by contact and/or fumigance, J.J.; Delgado Ávila, W.A.; Herrera and many of them had a strong repellent effect. -

Marla Maria Marchetti Ácaros Do Cafeeiro Em

MARLA MARIA MARCHETTI ÁCAROS DO CAFEEIRO EM MINAS GERAIS COM CHAVE DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Entomologia, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. VIÇOSA MINAS GERAIS - BRASIL 2008 MARLA MARIA MARCHETTI ÁCAROS DO CAFEEIRO EM MINAS GERAIS COM CHAVE DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Entomologia, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. APROVADA: 29 de fevereiro de 2008. Prof. Noeli Juarez Ferla Prof. Eliseu José Guedes Pereira (Co-orientador) Pesq. André Luis Matioli Prof. Simon Luke Elliot Prof. Angelo Pallini Filho (Orientador) “Estou sempre alegre essa é a maneira de resolver os problemas da vida." Charles Chaplin ii DEDICO ESPECIAL A Deus, aos seres ocultos da natureza, aos guias espirituais, em fim, a todos que me iluminam guiando-me para o melhor caminho. A minha família bagunceira. Aos meus amáveis pais Itacir e Navilia, pela vida maravilhosa que sempre me proporcionaram, pelos ensinamentos de humildade e honestidade valorizando cada Ser da terra, independente quem sejam, a minha amável amiga, empresária e irmã Magda Mari por estar sempre pronta a me ajudar, aos meus amáveis sobrinhos, meus maiores tesouros, são minha vida - Michel e Marcelo, ao meu cunhado Agenor, participação fundamental por eu ter chegado até aqui. Enfim, a vocês meus familiares, pelo amor, pelo apoio incondicional, pelas dificuldades, as quais me fazem crescer diariamente, pelas lágrimas derramadas de saudades, pelo carinho, em fim, por tudo que juntos passamos. Vocês foram e sempre serão o alicerce que não permitirão que eu caía. -

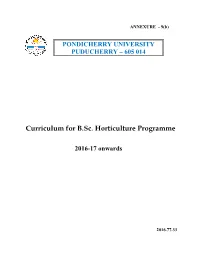

Curriculum for B.Sc. Horticulture Programme

ANNEXURE - 9(b) PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY PUDUCHERRY – 605 014 Curriculum for B.Sc. Horticulture Programme 2016-17 onwards 2016.77.33 CURRICULAM B.Sc. (HORTICULTURE) DEGREE PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT WISE DISTRIBUTION OF COURSES ABSTRACT No.of Credit Sl. No. Department / Discipline Total Credits Courses Hours 1. Horticulture 23 31+32 63 2. Agronomy 4 4+4 8 3. Agricultural Economics 2 3+2 5 4. Agricultural Extension 2 3+2 5 5. Agricultural Entomology 4 6+4 10 6. Agricultural Microbiology 1 1+1 2 7. Agricultural Engineering 1 1+1 2 8. Genetics and Plant Breeding 3 5+3 8 9. Seed Science and Technology 1 2+1 3 10. Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry 3 3+3 6 11. Plant Pathology 4 6+4 10 12. Nematology 1 1+1 2 13. Bio-Chemistry 1 2+1 3 14. Crop Physiology 1 1+1 2 15. Environmental Science 1 1+1 2 16. Computer Science and Statistics 2 1+2 3 17. Experiential Learning 2 0+28 28 Total Credit Courses 56 71+91 162 Non Credit Courses 18. English 2 0+2 2 19. NSS/NCC 1 0+1 1 20. PED 1 0+1 1 21. Short Tour 1 0+1 1 22. All India Tour 1 0+2 2 Total Non-Credit Courses 6 0+7 7 GRAND TOTAL 62 71+98 169 DEPARTMENT WISE DISTRIBUTION OF COURSES DEPARTMENT OF HORTICULTURE Sl. No. Course No. Course Title Cr.Hr. Semester Basic Horticulture 1. HOR 101 Fundamentals of Horticulture 2+1 I 2. HOR 102 Plant Propagation and Nursery Management 1+1 II 3. -

PESTS of STORED PRODUCTS a 'Pest of Stored Products' Can Refer To

PESTS OF STORED PRODUCTS A ‘pest of stored products’ can refer to any organism that infests and damages stored food, books and documents, fabrics, leather, carpets, and any other dried or preserved item that is not used shortly after it is delivered to a location, or moved regularly. Technically, these pests can include microorganisms such as fungi and bacteria, arthropods such as insects and mites, and vertebrates such as rodents and birds. Stored product pests are responsible for the loss of millions of dollars every year in contaminated products, as well as destruction of important documents and heritage artifacts in homes, offices and museums. Many of these pests are brought indoors in items that were infested when purchased. Others originate indoors when susceptible items are stored under poor storage conditions, or when stray individual pests gain access to them. Storage pests often go unnoticed because they infest items that are not regularly used and they may be very small in size. Infestations are noticed when the pests emerge from storage, to disperse or sometimes as a result of crowding or after having exhausted a particular food source, and search for new sources of food and harborage. Unexplained occurrences of minute moths and beetles flying in large numbers near stored items, or crawling over countertops, walls and ceilings, powdery residues below and surrounding stored items, and stale odors in pantries and closets can all indicate a possible storage pest infestation. Infestations in stored whole grains or beans can also be detected when these are soaked in water, and hollowed out seeds rise to the surface, along with the adult stages of the pests, and other debris. -

Potamopyrgus Antipodarum (Gray, 1843) (Gastropoda, Tateidae) in Chile, and a Summary of Its Distribution in the Country

16 3 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 16 (3): 621–626 https://doi.org/10.15560/16.3.621 Range extension of the invasive Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) (Gastropoda, Tateidae) in Chile, and a summary of its distribution in the country Gonzalo A. Collado1, 2, Carmen G. Fuentealba1 1 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad del Bío-Bío, Avenida Andrés Bello 720, Chillán, 3800708, Chile. 2 Grupo de Biodiversidad y Cambio Global, Universidad del Bío-Bío, Avenida Andrés Bello 720, Chillán, 3800708, Chile. Corresponding author: Gonzalo A. Collado, [email protected] Abstract The New Zealand mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) has been considered as one of the most invasive mollusks worldwide and recently was listed among the 50 most damaging species in Europe. In the present paper, we report for the first time the presence ofP. antipodarum in the Maule river basin, Chile. The identity of the species was based on anatomical microdissections, scanning electron microscopy comparisons, and DNA barcode analysis. This finding constitutes the southernmost record of the species until now in this country and SouthAmerica. Keywords Alien species, DNA barcode, cryptic species, invasive mollusks, Maule River, range distribution. Academic editor: Rodrigo Brincalepe Salvador | Received 05 February 2020 | Accepted 23 March 2020 | Published 22 May 2020 Citation: Collado GA, Fuentealba CG (2020) Range extension of the invasive Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) (Gastropoda, Tateidae) in Chile, and a summary of its distribution in the country. Check List 16 (3): 621–626. https://doi.org/10.15560/16.3.621 Introduction the 50 most damaging species in Europe (Nentwig et al. -

Dinâmica Populacional De Ácaros Em Cafezal Próximo a Fragmento Florestal E Conduzido Sob a Ação De Agrotóxicos No Município De Monte Alegre Do Sul - SP

1 Dinâmica Populacional de Ácaros em Cafezal Próximo a Fragmento Florestal e Conduzido sob a Ação de Agrotóxicos no Município de Monte Alegre do Sul - SP LUIZ HENRIQUE CHORFI BERTON Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. 2 DADOS DE CATALOGAÇÃO NA PUBLICAÇÃO (CIP) Núcleo de Informação e Documentação - Biblioteca Instituto Biológico Secretaria da Agricultura e Abastecimento do Estado de São Paulo Berton, Luiz Henrique Chorfi Dinâmica populacional de ácaros em cafezal próximo a fragmento florestal e conduzido sob a ação de agrotóxicos no município de Monte Alegre do Sul, SP / Luiz Henrique Chorfi Berton. – São Paulo, 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado) Instituto Biológico (São Paulo). Programa de Pós-Graduação. Área de concentração: Sanidade Vegetal, Segurança Alimentar e o Ambiente Linha de pesquisa: Biodiversidade: caracterização, interações, interações ecológicas em agroecossistemas. Orientador: Adalton Raga Versão do título para o inglês: Population dynamics of mites in a coffee plantation under pesticide treatment close to a forest fragment in Monte Alegre do Sul County, State of São Paulo. 1. Acarofauna em cafezal 2. Dinâmica populacional 3. Ação de agrotóxicos 4. Fragmento florestal 5. Monte Alegre do Sul, SP I. Raga, Adalton II. Instituto Biológico (São Paulo). Programa de Pós-Graduação III. Título IB/Bibl /2009/021 3 INSTITUTO BIOLÓGICO PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO Dinâmica Populacional de Ácaros em Cafezal Próximo a Fragmento Florestal e Conduzido sob a ação de Agrotóxicos no Município de Monte Alegre do Sul - SP LUIZ HENRIQUE CHORFI BERTON Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto Biológico, da Agência Paulista de Tecnologia dos Agronegócios, para obtenção do título de Mestre em Sanidade, Segurança Alimentar e Ambiental no Agronegócio. -

International Symposium on Biological Control of Arthropods 2005

Agusti et al. _________________________________________________________________________ Session 12: Environmental Risk Assessment of Invertebrate Biological Control Agents ESTIMATING PARASITISM LEVELS IN OSTRINIA NUBILALIS HÜBNER (LEPIDOPTERA: CRAMBIDAE) FIELD POPULATIONS USING MOLECULAR TECHNIQUES Nuria AGUSTI1, Denis BOURGUET2, Thierry SPATARO3, and Roger ARDITI3 1Dept. de Proteccio Vegetal Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentaries (IRTA) 08348 Cabrils (Barcelona), Spain [email protected] 2Centre de Biologie et de Gestion des Populations (CBGP) Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) Campus International de Baillarguet CS 30 016, 34988 Montferrier / Lez cedex, France [email protected] 3Ecologie des populations et communautés 76 Institut National Agronomique Paris-Grignon (INA P-G) 75231 Paris cedex 05, France [email protected] [email protected] Accurate detection and identification of parasitoids are critical to the success of IPM pro- grams to detect unusual variations of the density of these natural enemies, which may follow changes in agricultural practices. For such purposes specific molecular markers to detect Lydella thompsoni (Herting) and Pseudoperichaeta nigrolineata (Walker) (Diptera: Tachinidae) within the european corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) have been developed. Primers amplifying fragments of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene were designed following alignment of comparable sequences for a range of parasitoid and host species. Each of the primer pairs proved to be species-specific to one of those ta- chinid species, amplifying DNA fragments of 191 and 91 bp in length for L. thompsoni and P. nigrolineata, respectively. This DNA-based technique allowed to perform a molecular detec- tion of parasitism in natural populations of O. nubilalis. Molecular evaluation of parasitism was compared with the traditional method of rearing ECB populations in controlled conditions before breaking off the diapause. -

Przyroda Sudetów 9

Tom 9 2006 EUROREGION NEISSE - NISA - NYSA Projekt jest dofinansowany przez Unię Europejską ze środków Europejskiego Funduszu Rozwoju Regionalnego w ramach Programu Inicjatywy Wspólnotowej INTERREG IIIA Wolny Kraj Związkowy Saksonia – Rzeczpospolita Polska (Województwo Dolnośląskie), w Euroregionie Nysa oraz budżet państwa. oraz Wojewódzki Fundusz Ochrony Œrodowiska i Gospodarki Wodnej we Wroc³awiu 1 MUZEUM PRZYRODNICZE w JELENIEJ GÓRZE ZACHODNIOSUDECKIE TOWARZYSTWO PRZYRODNICZE PRZYRODA SUDETÓW ROCZNIK Tom 9, 2006 JELENIA GÓRA 2006 2 PRZYRODA SUDETÓW t. 9(2006): 3-6 Jacek Urbaniak Redaktor wydawnictwa ANDRZEJ PACZOS Redaktor naczelny BOŻENA GRAMSZ Stanowisko Nitella syncarpa Zespó³ redakcyjny BO¯ENA GRAMSZ (zoologia) CZES£AW NARKIEWICZ (botanika) (THUILL .) CHEVALL . 1827 (Charophyta) ANDRZEJ PACZOS (przyroda nieożywiona) Recenzenci TOMASZ BLAIK (Opole), ADAM BORATYŃSKI (Kórnik), w masywie Gromnika MAREK BUNALSKI (Poznań), ANDRZEJ CHLEBICKI (Kraków), ANDRZEJ HUTOROWICZ (Olsztyn), LUDWIK LIPIŃSKI (Gorzów Wlkp.) ADAM MALKIEWICZ (Wrocław), PIOTR MIGOŃ (Wrocław), ROMUALD MIKUSEK (Kudowa Zdrój), JULITA MINASIEWICZ (Gdańsk), TADEUSZ MIZERA (Poznań), KRYSTYNA PENDER (Wrocław), Wstęp ŁUKASZ PRZYBYŁOWICZ (Kraków), PIOTR REDA (Zielona Góra), TADEUSZ STAWARCZYK (Wrocław), EWA SZCZĘŚNIAK (Wrocław), W polskiej florze ANDRZEJ TRACZYK (Wrocław), WANDA M. WEINER (Kraków), ramienic (Charophyta) JAN ŻARNOWIEC (Bielsko-Biała) występuje pięć z sze- ściu rodzajów z tej T³umaczenie streszczeñ (na j. niemiecki) ALFRED BORKOWSKI wysoko uorganizowa- (na j. czeski) JIØÍ DVOØÁK nej gromady glonów, a mianowicie: Chara, Dtp „AD REM”, tel. 075 75 222 15, www.adrem.jgora.pl Nitella, Nitellopsis, Tolypella i Lychno- Opracowanie thamnus. Najbardziej kartograficzne „PLAN”, tel. 075 75 260 77 (str. 72, 146, 148) rozpowszechnionym, nie tylko w Polsce, ale Druk ANEX, Wrocław i w całej Europie, jest rodzaj Chara, którego Nak³ad 1200 egz. -

Selective Arcing Electrostatically Eradicates Rice Weevils in Rice Grains

insects Article Selective Arcing Electrostatically Eradicates Rice Weevils in Rice Grains Koji Kakutani 1, Yoshihiro Takikawa 2,* and Yoshinori Matsuda 3 1 Pharmaceutical Research and Technology Institute and Anti-Aging Centers, Kindai University, Osaka 577-8502, Japan; [email protected] 2 Plant Center, Institute of Advanced Technology, Kindai University, Wakayama 642-0017, Japan 3 Laboratory of Phytoprotection Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kindai University, Nara 631-8505, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Rice stored in warehouses is frequently attacked by rice weevils, which must therefore be controlled. We developed an electrostatic method as an alternative to pesticides. An arc discharge exposer (ADE) kills insects entering an electric field. The apparatus has pairs of identical metal plates, one of which is linked to a voltage generator for negative charging, the other is grounded. A −7 kV electric field forms between the two plates. When an insect enters the electric field it is arced by the charged plate and killed. We combined this method with a technique that lures insects hiding in rice grains. When a vessel containing rice and insects was rotated and then returned to the initial position, the weevils climbed up the vessel walls and entered the ADE. Dead insects were collected to minimize rice contamination. This method efficiently killed pests in stored rice. Abstract: We developed an arc discharge exposer (ADE) that kills rice weevils nesting in dried rice. The ADE features multiple identical metal plates, half of these are linked to a voltage generator and Citation: Kakutani, K.; Takikawa, Y.; the others are grounded. -

Diatomaceous Earth As Insecticide Rice Weevil

Pest Control Newsletter Issue No.43 July 2016 Published by the Rice weevil Pest Control Advisory Section Issue No.43 JULY 2016 The rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae, is one of the 300 to 400 eggs in her average lifetime of four INSIDE Diatomaceous Earth most economically important pests of stored whole to five months. The egg hatches into a legless THIS Rice weevil grains in the world. This weevil is widely distributed larva which has a short, stout, whitish body and ISSUE as Insecticide worldwide in warmer regions. They are usually tan head. It feeds on the interior of the grain found in grain storage facilities or processing plants, kernel. When mature, the larva changes to a infesting rice, wheat, oats, corn, nuts, rye, and barley. white pupa and later emerges as an adult beetle. At home, infestations are generally found in rice, The adult can fly and is attracted to light. They feign Diatomaceous Earth as Insecticide beans, sunflower seeds, whole corn, and occasionally death when disturbed by drawing their legs close to in old pasta such as macaroni and spaghetti. the body and then lying still for several minutes. Rice weevils are harmless to people, pets, furniture Diatomaceous Earth (DE) is a naturally occurring, soft, or get into the eyes. To achieve effective pest control, and clothes. They do not bite, sting or transmit siliceous sedimentary rock that is easily crumbled into sanitation efforts are keys. Elimination of food sources diseases. The damage they do is destruction of the a fine white powder. It contains fossilized remains of and harbouraging places for pests are the basic and grains they infest.