Mental Health & Suicide Prevention Service Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, and CONSERVATION in ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S a CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman

3 KUNINJKU PEOPLE, BUFFALO, AND CONSERVATION IN ARNHEM LAND: ‘IT’S A CONTRADICTION THAT FRUSTRATES US’ Jon Altman On Tuesday 20 May 2014 I was escorting two philanthropists to rock art galleries at Dukaladjarranj on the edge of the Arnhem Land escarpment. I was there in a corporate capacity, as a direc- tor of the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust, seeking to raise funds to assist the Djelk and Warddeken Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) in their work tackling the conservation challenges of maintain- ing the environmental and cultural values of 20,000 square kilometres of western Arnhem Land. We were flying low in a Robinson R44 helicopter over the Tomkinson River flood plains – Bulkay – wetlands renowned for their biodiversity. The experienced pilot, nicknamed ‘Batman’, flew very low, pointing out to my guests herds of wild buffalo and their highly visible criss-cross tracks etched in the landscape. He remarked over the intercom: ‘This is supposed to be an IPA but those feral buffalo are trashing this country, they should be eliminated, shot out like up at Warddeken’. His remarks were hardly helpful to me, but he had a point that I could not easily challenge mid-air; buffalo damage in an iconic wetland within an IPA looked bad. Later I tried to explain to the guests in a quieter setting that this was precisely why the Djelk Rangers needed the extra philanthropic support that the Karrkad-Kanjdji Trust was seeking to raise. * * * 3093 Unstable Relations.indd 54 5/10/2016 5:40 PM Kuninjku People, Buffalo, and Conservation in Arnhem Land This opening vignette highlights a contradiction that I want to explore from a variety of perspectives in this chapter – abundant populations of environmentally destructive wild buffalo roam widely in an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) declared for its natural and cultural values of global significance, according to International Union for the Conservation of Nature criteria. -

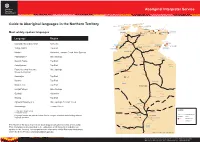

Aboriginal Interpreter Service

Aboriginal Interpreter Service CROKER ISLAND Guide to Aboriginal languages in the Northern Territory MELVILLE ISLAND Iwaidja GOULBURN ISLANDS BATHURST ISLAND Maung Tiwi ELCHO ISLAND GALIWIN’KU WURRUMIYANGA Ndjebbana MILINGIMBI MANINGRIDA NHULUNBUY DARWIN Burarra Yolngu Matha YIRRKALA Most widely spoken languages GUNBALANYA Kunwinjku RAMINGINING GAPUWIYAK JABIRU Language Region UMBAKUMBA East Side/West Side Kriol Katherine Ngan'gikurrunggurr Nunggubuyu ANGURUGU GROOTE EYLANDT WADEYE East Side Kriol KATHERINE NUMBULWAR Yolngu Matha Top End Anindilyakwa Murrinh Patha NGUKURR West Side Kriol URAPUNGA Warlpiri Katherine, Tennant Creek, Alice Springs HIGHWAY Pitjantjatjara Alice Springs VICTORIA Yanyuwa BORROLOOLA Murrinh Patha Top End Ngarinyman Anindilyakwa Top End Garrwa DAGURAGU Eastern/Central Arrernte, Alice Springs STUART Gurindji Western Arrarnta + KALKARINDJI ELLIOTT Kunwinjku Top End LAJAMANU HIGHWAY Burarra Top End Warumungu Warlpiri BARKLY Modern Tiwi Top End TENNANT CREEK HIGHWAY Luritja/Pintupi Alice Springs Gurindji Katherine ALI CURUNG Alyawarr Maung Top End Alyawarr/Anmatyerr + Alice Springs, Tennant Creek Anmatyerr Warumungu Tennant Creek YUENDUMU Luritja/Pintupi LEGEND Western Desert family PAPUNYA + Arandic family Western Tiwi...................LANGUAGE GROUP Language families are indicated where there is a degree of mutual understanding between Arrarnta ALICE SPRINGS JABIRU .........TOWN language speakers. HERMANNSBURG Eastern/Central Arrernte ELLIOTT ............REMOTE TOWN BARUNGA .........COMMUNITY The Northern Territory -

Northern Territory Emergency Response: Report of the NTER

NORTHERN TERRITORY EMERGENCY RESPONSE REPORT OF THE NTER REVIEW BOARD October 2008 i © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca First published October 2008. Produced by the Australian Government. Disclaimer The opinions, comments and /or analysis expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs or the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, and cannot be taken in any way as expressions of government policy. ii JENNY MACKLIN MP Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Dear Minister The Board would like to present our report reviewing the Northern Territory Emergency Response, in accordance with our Terms of Reference, issued on 6 June 2008. We thank you for the privilege of undertaking the review and offer our report in the sincere hope that it will assist the Australian Government to improve the safety and wellbeing of Aboriginal children -

Annual Report 2004

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY About this Report 2 About the Association 3 Vision, Mission, Core Values and Goals 4 Membership 2004 – 2005 5-6 Local Governing Bodies in the Northern Territory 7 Executive Committee Members 8 Executive Profiles 9-11 Staff 13-15 Organisational Structure 16 Service Providers & Sponsors 17 President’s Report on Behalf of the Executive 18-27 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 28 Strategic Plan Achievements 2004/2005 29-40 Financial Statements for the Year Ended 30 June 2005 41 Independent Audit Report to the Members of the Local Government 42-43 Association of the Northern Territory Statement of Financial Position as at 30 June 2005 44 Statement of Income and Expenditure for the Year Ended 30 June 45-49 2005 Statement of Cash Flows for the Year Ended 30 June 2005 50 Notes to, and forming part of, the Financial Statements for the Year 51-55 Ended 30 June 2005 Local Government Association of the Northern Territory 2004/2005 56-58 Actual versus Budget to 30 June 2005 Official publication of the Local Government Association of the Northern Territory © 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Members of the Association This report is the 14th Annual Report of the Local Government Association of the Northern Territory and it is for the financial year 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2005. This report has been prepared in compliance with the Association's Constitution for the members of the Association. However, many other persons and organisations will find it informative for their own purposes. -

Local Authority Meeting Agenda

Borroloola Local Authority Meeting Agenda To be held at the Conference Room, Council Services Centre Thursday 11th February 2016 1. Present: 1.1 Elected Members: 1.2 Local Authority Members: 1.3 Staff: 1.4 Visitors/Guests: PLEDGE: “We pledge to work as one towards a better future through effective use of all resources. We have identified these key values and principles of Honesty, Equality, Accountability, Respect, and Trust as being integral in the achievement of our vision that the Roper Gulf Regional Council is Sustainable, Viable and Vibrant”. 2. Apologies: Apologies Accepted Moved: Seconded: 3. Conflict of Interest-Members & Staff: . 4. Minutes of Previous Meeting: Minutes from the previous meeting held on 5th November 2015 pg: 5-9 Motion: That the Borroloola Local Authority accepts the Minutes from the previous Local Authority Meeting held on Thursday 5th November 2015 as a true and accurate record of the meeting. Moved: Seconded: 5. Business Arising/Action List; 5.1. Previous minutes action List Date Item Description Responsible Status Status Comments - Person Completion Date 5.06.2014 LA recommends a Waste DITS Ongoing Action incorporated into Management Strategy is drawn up for RGRC Waste Management the Borroloola region, including Strategy. A newly formed recycling capability and planning for Waste Management Strategy future Committee is driving this Action. * Denotes permanent Agenda items 5.06.2014 LA recommends that Council actively Council Ongoing 10.09.2015-Recommendation: watch & provide information on status Invite NTG Community of housing in Borroloola with regard to Housing & Freehold SIHIP money. Subdivision reps to next LA Mtg for update. -

Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life

Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISSN 1030-522X With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document, the Northern Land Council Annual Report 2017/18, is provided under a Creative Commons Licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website at creativecommons.org/licences/ by/3.0/au/, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3 AU licence Red Flag Dancers perform at Ngukurr. NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 OUR VALUES ... OUR VISION … We will: is to have the land and sea rights of • Consult with and act with the informed Traditional Owners and affected Aboriginal consent of Traditional Owners in accordance people in the Top End of the Northern with the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. Territory recognised and to ensure that Aboriginal people benefit socially, • Communicate clearly with Aboriginal culturally and economically from the secure people, taking into account the possession of our land, waters and seas. linguistic diversity of the region. • Respect Aboriginal law and tradition. WE AIM TO… • Be responsive to Aboriginal peoples’ needs achieve enhanced social, political and and effectively advocate for their interests. economic participation and equity for Aboriginal people through the promotion, • Be accountable to the people we represent protection and advancement of our land • Behave in a manner that is appropriate rights and other rights and interests. and sensitive to cultural differences. • Act with integrity, honesty and fairness. -

Welcome to Jabiru Handbook

2021 JABIRU RESIDENTS' HANDBOOK Welcome TO JABIRU EDITION 16 Front page photography courtesy: Peter Keepence Photography Andy Ralph 2021 JABIRU RESIDENTS' HANDBOOK Welcome TO JABIRU EDITION 16 This handbook was made possible by West Arnhem Regional Council and the dedicated members, businesses, community groups and organisations of the Jabiru community. Thank you to those who have contributed photographs which appear throughout the booklet over the years. Contents Restrictions 22 6.1 Alcohol 22 Jabiru town map 7 6.2 Permits and Aboriginal Land 23 Getting settled in Jabiru 9 6.3 Road Conditions and Access 24 1.1 Post Office 9 6.4 Animals 24 1.2 Banking 9 6.5 Plants 24 1.3 Telephone and Internet 9 6.6 Fishing and Boating 25 1.4 Power 9 6.7 Bats 26 1.5 Television and Radio Transmission 10 1.6 Drivers Licence and MVR 10 Education 28 1.7 Electoral Roll 11 7.1 Jabiru Area School 28 1.8 Rubbish Removal 11 7.2 Department of Business (DoB) 29 1.9 Insurance 11 7.3 Charles Darwin University (CDU) 29 Climate 12 Churches 30 2.1 The Six Seasons of Kakadu 12 8.1 Uniting Churc 30 2.2 The Three Seasons of the Top End 12 8.2 Catholic Church 30 8.3 Donations 30 Emergency Services 14 3.1 Emergency Services 14 Shopping 31 3.2 Police Station 14 9.1 Foodland Supermarket 31 3.3 Health Centre 14 9.2 Two Rivers Newsagency 31 3.4 Fire Station 14 9.3 Mercure Kakadu Crocodile Hotel 32 3.5 Disasters 15 9.4 Marrawuddi Arts & Culture 32 9.5 Airport Gift Shop 32 Safety Information 16 9.6 Jabiru Service Station 32 4.1 Fire Extinguishers 16 4.2 Smoke Detectors 16 Recreation -

Morgue Management on Remote Communities in the Northern Territory

INVESTIGATION REPORT INTO MORGUE MANAGEMENT ON REMOTE COMMUNITIES IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Kalkaringi Morgue Lajamanu Morgue Alpurrurulam Morgue “WE OWE RESPECT TO THE LIVING BUT TO THE DEAD WE OWE …??” Voltaire (1785) Page 1 of 79 Table of Contents TRANSMISSION LETTER........................................................................................................................ 4 ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 9 BACKGROUND - KALKARINGI MORGUE ......................................................................................... 10 KALGARINGI MORGUE PHOTOS .................................................................................................... 10 DEFINITIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 11 MORGUE: ...................................................................................................................................... 11 REPORTABLE DEATH ..................................................................................................................... 11 CORONERS ACT ............................................................................................................................ -

Indigenous Employment Opportunities

Fact sheet Indigenous Employment Opportunities Northern Territory Government (NTG) is committed to increasing employment opportunities and growing the capacity of Indigenous businesses to successfully share in the delivery of construction projects in the Northern Territory. NTG Contractors perform an integral role in this by providing employment and training opportunities and improving the participation rate of Indigenous employees, trainees and apprentices directly employed through NTG contracts. Indigenous Participation on Construction Projects Policy To support Indigenous employment, skills development and retention opportunities on construction projects, an Indigenous Development Plan (IDP) is mandated in all Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Logistics contracts above $500 000 under the Indigenous Participation on Construction Projects Policy. The purpose of an IDP is for contractors to develop strategies and protocols within the Department’s contracts that support Indigenous enterprise and maximise employment and training opportunities for Indigenous Territorians. Consideration is also given to this Policy when assessing procurement activities under $500 000. Compliance audits of tenders and contracts are also regularly undertaken against the IDP requirements. To achieve an increase in Indigenous participation, contractors are required to provide proposals in the tender response schedule to allow for assessment of: Indigenous employees, including apprentices/trainees directly employed on the works; the intended use of group training schemes or recognised Territory Indigenous community organisations to deliver the proposed works; and nominated sub-contractors usage of Indigenous employees, including registered Indigenous apprentices or trainees. More Information If you are interested in further information about the Indigenous Participation on Construction Projects Policy and Indigenous Development Plan’s please visit www.dipl.nt.gov.au/industry ; or call Director, Aboriginal Development, Michael Rotumah on 8924 7264. -

Climate Change Risk Assessment and Adaptation Planning

Local Government Association of the Northern Territory 29 November 2010 Climate Change Risk Assessment and Adaptation Planning West Arnhem Shire Council 1.1 Climate Change Risk Assessment and Adaptation Planning AECOM Climate Change Risk Assessment and Adaptation Planning West Arnhem Shire Council Prepared for Local Government Association of the Northern Territory Prepared by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd Level 2, 60 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia T +61 2 6201 3000 F +61 2 6201 3099 www.aecom.com ABN 20 093 846 925 29 November 2010 Funded with the assistance of the Australian Government Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. © AECOM Australia Pty Ltd 2010 The information contained in this document produced by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd is solely for the use of the Client identified on the cover sheet for the purpose for which it has been prepared and AECOM Australia Pty Ltd undertakes no duty to or accepts any responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. All rights reserved. No section or element of this document may be removed from this document, reproduced, electronically stored or transmitted in any form without the written permission of AECOM Australia Pty Ltd. Disclaimer AECOM has exercised reasonable care when completing this report. However, caution must be taken when considering our conclusions because significant uncertainty remains due to the inherent complexities involved in analysing the past climate and variables typically encountered when modelling future climate change. AECOM cannot guarantee the accuracy of the climate observations and projections described in this report and cannot be responsible for any third party’s reliance upon on this information. -

Barkly Shire Council Will Be Held in Tennant Creek on Thursday, 20 February 2014 at 08.30Am

BARKLY REGIONAL COUNCIL Vision A strong, cohesive Barkly Shire working as one to champion regional development to provide sustainable economic growth and community capacity where people embrace cultural diversity and are treated equitably and with respect. The way we will work By leading the Barkly Region to achieve an organisation that realises excellence in its governance and operational responsibilities and with a community service ethic and is co- operative, innovative and efficient. AGENDA ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING THURSDAY, 20 FEBRUARY 2014 The Ordinary Council Meeting of the Barkly Shire Council will be held in Tennant Creek on Thursday, 20 February 2014 at 08.30am. Edwina Marks Chief Executive Officer BARKLY REGIONAL COUNCIL COUNCIL PRAYER Our Lord Jesus Christ, we trust you will guide and bless this meeting of the Barkly Regional Council. We pray that you will ensure that all discussions and decisions made today are just and fair as they will affect all people within the Barkly Region. We also pray for your guidance to ensure that all our dealings are appropriate to all those whom we represent and will reflect an equitable and honest approach to the issues to be discussed today. Amen TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM SUBJECT PAGE NO MEETING TO COMMENCE WITH PRAYER AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS 1 OPENING & ATTENDANCE 1.1 Present: 1.2 Apologies and Leave of Absence: 1.2.1 LEAVE OF ABSENCE - CR. MAHONEY 1.2.2CR. BONNEY 1.3 Absent without Apology 2 CONFIRMATION OF COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES 2.1 Council Meeting Minutes - 12 December 2013 3 BUSINESS ARISING REPORT 4 LOCAL BOARD MEETING MINUTES AND BUSINESS ARISING 4.1 WUTUNUGURRA Local Board Minutes-29 Jan 2014 4.1.1 BUSINESS ARISING 4.2 ELLIOTT Local Board Minutes - 4 Feb 2014 4.2.1 BUSINESS ARISING 4.3 TENNANT CREEK Local Board Minutes - 5 Feb 2014 4.3.1 BUSINESS ARISING 4.4 ALI CURUNG Local Board Minutes - 11 Feb 2014 - LATE 4.4.1 BUSINESS ARISING 5 COUNCILLORS' WARD REPORTS 5.1 CR.