Points of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographs in Bold Acacia Avenue 64 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Alcohol 162–3 Aldgate 12 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Ashford In

smoothly from harrow index Cobb, Richard 173 Evening Standard 71, 104 INDEX Coffee 148–9 Fenchurch Street station 50, 152, 170 Collins, Wilkie 73 Film 102, 115 Conan Doyle, Arthur 27 Fleet line 210 Photographs in bold Conrad, Joseph 138 Food 146–7, 162. 188, 193 Cornford, Frances 78 Forster, EM 212 Acacia Avenue 64 Blake, William 137 Cortázar, Julio 163 Freesheets (newspapers) 104 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Bond, James 25, 102, 214 Crash (novel) 226 Freud, Sigmund 116, 119 Alcohol 162–3 Bowie, David 54, 55, 56, 90 Crossrail 204 Frisch, Max 13 Aldgate 12 Bowlby, Rachel 191 Cufflinks 156 Frotteurism 119 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Bowler hat 24 Cunningham, Gail 112 Fulham 55 Ashford International station 121 Bridges, in London 12, 32, 101, 154 Cyclist see Bicycles Gaiman, Neil 23 Austen, Jane 59 Briefcase 79 Dagenham 198 Galsworthy, John 173 Baker Street station 168, 215 Brighton 54 Dalston 55 Garden Cities 76–7, 106, 187 Balham station 134 Brixton 55 Davenant, William 38 Good Life, The (TV series) 54, 59, 158 Ball, Benjamin 116 Bromley 55 Davies, Ray 218 Guildford 64, 206 Ballard, JG 20, 55, 72, 112, 226 Bromley-by-Bow station 102, 213 De Botton, Alain 42, 110, 116 Great Missenden 60–1 Banbury 127 Buckinghamshire 20, 54, 57, 64 Deighton, Len 41 Green, Roger 16, 96, 229 Bank station 138, 152, 153 Burtonwood 36 De La Mare, Walter 20 Hackney 8, 13, 65, 121 Barker, Paul 54, 56, 81 Buses 15, 41, 111, 115, 129, 130, Derrida, Jacques 117 Hamilton, Patrick 114 Barking 213 134, 220–1 Diary of a Nobody, The 11, 23, 65, 195 Hampstead 54, 58, 121 Barnes, Julian -

Lo Ve T He Loc a T

LONDON SW17 Vibrant, fashionable with a bustling the best of just about everything. community what better place for you to Sports enthusiasts will enjoy the own your own home. opportunities that Tooting Bec Common SW17 has a lively social scene with has to offer, from the outdoor lido to the an eclectic mix of venues to enjoy a night tennis courts, football pitches and fishing out or a day in the park with friends. lake. Tooting Bec Common is just under a Enjoy a wide selection of supermarkets, mile from Balham Place and provides some independent retail shops, bars and welcome green space throughout restaurants as well as a street market the season. and a weekly farmers’ market. This understandably in-demand address And with the retail attractions of Chelsea offers a generous supply of everything that & Fulham just across the Thames and Central modern life demands and with our choice of London easily accessed from 266 @ Balham, superb apartments at the heart of it all, it you don’t have to venture that far to enjoy may well be your perfect place to call home. LOVE THE LOVE LOCATION CLAPHAM BALHAM CLAPHAM WATERLOOB237 VICTORIA SOUTHCHARING BANK LIVERPOOL ST Northern line SOUTH 15 mins 17 mins CROSS 19 mins 26 mins 2 mins 18 mins BALHAM CLAPHAM CENTRALVICTORIA WEST A205 BR JUNCTION 12LONDON mins CROYDON 5NIGHTINGALE mins LANE 20 mins BALHAM CLAPHAM STREATHAM BRIXTON TOOTING ELEPHANT KENNINGTON HIGH RD COMMON 24 mins 25 mins 28 mins & CASTLE 50 mins 18 mins 38 mins Balham is the last stop on the Northern Cycle around London on a Santander Cycle, BALHAM GROVE CAVENDISH ROAD CAVENDISH ATKINS ROAD Line and connects you to The City and the there’s a docking station at Vauxhall and you West End so an easy choice for commuting. -

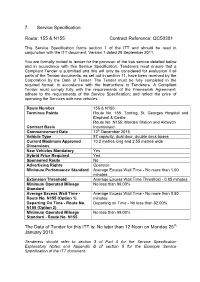

7. Service Specification Route: 155 & N155 Contract Reference

7. Service Specification Route: 155 & N155 Contract Reference: QC50301 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Route Number 155 & N155 Terminus Points Route No. 155: Tooting, St. Georges Hospital and Elephant & Castle Route No. N155: Morden Station and Aldwych Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 12th December 2015 Vehicle Type 87 capacity, dual door, double deck buses Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.55 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.00 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 0.85 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard Average Excess Wait Time - Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 0.80 Route No. -

London Underground Limited

Background Paper 1 Developing the Network 1 Introduction 1.1 Bus use has increased by over two-thirds since 1999, driven by sustained increases in the size and quality of the network, fares policy and underlying changes in London’s economy. The bus network is constantly evolving as London develops and the needs and aspirations of passengers and other stakeholders change. Enhancements take place not only to the service pattern but across all aspects of the service. • Capacity. The level of bus-km run has increased by around 40 per cent over the same period. Network capacity has increased by a faster rate, by around 55 per cent, with increases in average vehicle size. Additionally, much improved reliability means that more of the scheduled capacity is delivered to passengers. • Reliability. Effective bus contract management, in particular the introduction of Quality Incentive Contracts, has driven a transformation of reliability. This has been supported by bus priority and by the effects of the central London congestion charging scheme. Service control has been made more efficient and effective by iBus, TfL’s automatic vehicle location system. 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 Excess Wait Time (mins) 1.0 0.5 0.0 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985/86 1987/88 1989/90 1991/92 1993/94 1995/96 1997/98 1999/00 2001/02 2003/04 2005/06 2007/08 2009/10 2011/12 2013/14 Figure 1: Excess Waiting Time on high-frequency routes – since 1977 • Customer service. All bus drivers must achieve BTEC-certification in customer service and other relevant areas. -

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner's Report This Paper Will Be Considered in Public 1 Summary 2 Recommendation

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner’s Report This paper will be considered in public 1 Summary 1.1 This report provides an overview of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. 2 Recommendation 2.1 That the Board note the report. List of appendices to this report: Commissioner’s Report – February 2016 List of Background Papers: None Mike Brown MVO Commissioner Transport for London February 2016 Commissioner’s Report 03 February 2016 This paper will be considered in public 1 Introduction This report provides a review of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. Cover image: ZeEus London trial launch at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park 2 Commissioner’s Report 2 Delivery A full update on operational performance the successful conclusion of talks with the will be provided at the next Board meeting Trades Unions. We continue to work with on 17 March in line with the quarterly the Trades Unions to avoid unnecessary strike Operational and Financial Performance action, and reach an agreement on rosters and Investment Programme Reports. and working practices. Mayor’s 30 per cent Lost Customer LU has taken the decision to implement its Hours target – London Underground long term solution for Train Drivers, recruiting Following significant improvements in the part-time drivers specifically for the Night reliability of London Underground’s train Tube. These vacancies were advertised services, the Mayor set a target in 2011 internally and externally before Christmas, with aiming to further reduce delays on London more than 6,000 applications received, which Underground (LU) by 30 per cent by the end are now being processed. -

The Experience of Sheltering in the Tube During WWII

TfL Corporate Archives Research Guides: World War II 75th Anniversary Edition The Experience of Sheltering in the Tube during WWII What was it like to shelter in the tubes? Using original archival material and first hand accounts from the Transport for London collections, we bring you the story of the shelterers, both known and unknown.... Archive ref num: LT000503/036 In early September 1940, crowds gathered outside Liverpool Street underground station demanding to be let in to take shelter from the first bombings of what would become known as 'The Blitz'. A 1924 Government directive had ruled out the use of stations as shelters in the event of air raids but Londoners had other ideas. Many bought tickets for the tube and then simply refused to leave. During an oral history interview in 2017, Les Gaskin, a child shelterer in 1940, explained: "We used to go down there to find somewhere to sleep....you had to buy a ticket...to get down there...they didn't want people on the Underground initially but if you bought a ticket that was it!" This prompted the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) to take control. Once the decision was made to formally admit shelterers, they came in their thousands. On the 21st September 1940 around 120,000 people were seeking refuge in London’s underground stations. By October this had risen to 124,000, with 2,750 sheltering at King’s Cross alone. A graph showing the number of people sheltering in Tube stations and tunnels between A utumn 1940 and April 1941. -

Underground News Index 1996

UNDERGROUND NEWS ISSN 0306-8617 INDEX 1996 Issues 409-20 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE LONDON UNDERGROUND RAILWAY SOCIETY 554 555 INDEX TO 1996 ISSUES OF UNDERGROUND NEWS A (continued) Aldwych station, 13 Notes (i) Page entries with * are photographs Alperton station, 390 (ii) Page entries for an individual station may include developments in the general vicinity of the station. Amersham station, 400 Arnos Grove station, 100,429 A Arsenal station, 375 Attlee, Mr.C, Metropolitan passenger, 253 ACCIDENTS - COLLISIONS Auction of relics including 1962 stock 5.12.95, 88,90,103,125 Baker Street, bufferstops, 9.6.96, 340 Charing Cross, District, 8.5.38, 330 B Lorry with Debden canopy, 6.2.96, 196 Baker Street station, 68,78,132,294 tyloorgate, 28.2.75, 66,67,330 BAKERLOO LINE Road vehicles with South Ruislip bridge, 467,469 Closure south of Piccadilly Circus, 45,125,126,129,483,497,535 Royal Oak. Thames Trains, November 1995, 84,103,106 Dot Matrix indicators display rude messages, 21 Toronto Underground, 9.8.1995, 121,256 Features when extended to Elephant in 1906, 467 Train with tool storage bin, near Hampstead, 375 Baku, metro train fire disaster, 19,20,66 Train, with engineers' trolley, nr.Belsize Park, 537 Balham station, 106,370 Watford, North London Railways, 8.8.96, 452,468 Bank station, 19,32,93,100,222,231,370 ACCIDENTS - DERAILMENTS Barbican station, 26,500 Finchley Central, 1.6.96, 339 Barcelona metro, 189,535 Golders Green, 16.7.96, 405 Barking station, 185,282,534' Hainault depot, 11.5.96, 271 Barons Court station, 108 Match wagon, Ruislip connection. -

103 Balham Hill Balham SW12 9PD

103 Balham Hill Balham SW12 9PD PROMINENT COMMERCIAL UNIT FRONTING BALHAM HILL | AVAILABLE NOW Area: 4,491 FT2 (417 M2) Initial Rent: £92,500 PA LOCATION FRONTAGE Balham Hill Prominent USE CONSENT AVAILABILITY A1 / B1c / B8 Immediately PARKING TUBE Forecourt Northern Line TRAIN SECURE YARD Balham Station Approx. 7,911 sq.ft. 3 PHASE POWER AREA On-site www.houstonlawrence.co.uk Continued [email protected] 103 Balham Hill Balham SW12 9PD CONTACT: George Rowling 0207 801 9027 [email protected] LOCATION: DESCRIPTION: Positioned fronting Balham Hill, the prominent commercial The available commercial property comprises a two storey Andrew Cordery premises is situated in a popular residential and commercial building fronting Balham Hill (A24). The front of the site is location and benefits from a high volume of passing traffic, currently configured as a trade counter, office and storage 0207 801 9021 as well as high footfall. area. [email protected] 103 Balham Hill is a short walk from Clapham South The building benefits from single storey covered storage and underground (Northern line) providing easy access into an open yard area to the rear along with forecourt parking at Central London. Balham underground (Northern line) and the front on the site. national rail station (providing access to and from London Victoria, Sutton, Milton Keynes and Croydon) is approx 10 The premises are held by way of an original lease from 10th minutes' walk from the property. December 1999 for a term of 25 years. There is a reversionary lease expiring on 31st October 2035 with www.houstonlawrence.co.uk FLOOR AREA: reviews in 2024, 2029 and 2034. -

Autumn 2015 Crossrail 2 Consultation

Our response to issues raised Autumn 2015 Crossrail 2 Consultation 7 July 2016 Crossrail 2 7 July 2016 Foreword 9 Introduction 13 1. Construction impacts 15 1.1. Concern about disruption to local residents and businesses 15 1.2. Concern about disruption to road traffic and congestion 15 1.3. Concern about demolition and damage to residential buildings 16 1.4. Concern about how excavated waste will be disposed of 16 1.5. Concerns about construction impacts on nearby schools 16 2. Capacity and crowding 17 2.1. Concern that Crossrail 2 is not beneficial or necessary 17 2.2. Concern about loss of fast and direct services to Waterloo from southwest London and Surrey 17 2.3. Concerns that planned frequency/capacity of trains on regional branches of the National Rail network served by Crossrail 2 will not be sufficient 18 2.4. Concerns that Crossrail 2 would increase, rather than reduce, the burden on the Tube network 18 2.5. Concerns about crowding and congestion at Crossrail 2 stations 19 2.6. Suggestion that existing stations would require improvements to car parking 19 2.7. Suggestions to enhance the current station buildings as part Crossrail 2 works on the existing Network Rail sections 19 3. Social and environmental 20 3.1. Overarching concerns about the environmental impacts of Crossrail 2 20 3.2. Concern about the loss of green space during construction 20 3.3. Concern about noise and vibration from the running of trains causing disruption to residential housing and businesses along the route 21 3.4. -

South London Sub-Regional Transport Plan – 2012 Update

South London Sub-regional transport plan – 2012 update MAYOR OF LONDON 1 2 Introduction Publication of the sub-regional transport e.g. through borough LIPs and through the Battersea and to renew the safeguarding of It is for the sub-regional Panel, formed of plans in November 2010 reflected sub-regional Panels, to be taken account the Chelsea – Hackney route in 2014 . This the participants of the South London significant collaboration and joint work of. will provide an opportunity to ensure a Transport Strategy Board to discuss this between TfL, boroughs, sub-regional future scheme best serves future needs as draft update and agree the next steps. I partnerships and London Councils as well Over the past year there have been some currently perceived. would welcome engagement and as a range of other stakeholders. notable successes for London’s transport comments on the content and process so system, many of them on the national and The financial context remains constrained, that together we can continue to plan this It is now just over a year since the plans TfL rail networks. The Secretary of State’s but, it remains vital that we look beyond the great city and ensure that the south sub- were published. The sub-regional process recent announcement on High Speed 2 current Business Plan, continuing to plan region fulfils its potential. is an ongoing programme, enabling TfL to marks an important milestone for a project and address the challenges which a work closely with boroughs to address which offers enormous potential to growing population brings. In fact rather Peter Hendy Jan 2012 strategic issues, progress medium-longer strengthen our ability to generate economic than diminishing the importance of this, the term priorities and also respond to changing growth in the future. -

Streatham Action's Crossrail 2 Consultation Submission

Streatham Action’s Crossrail 2 Consultation submission Overview This consultation report is submitted to Crossrail 2 by Streatham Action – a cross-party and non-party affiliated lobbying group of volunteers that seeks improvements for the residents in central Streatham in key areas including transport and planning. Streatham Action recommends that the Crossrail 2 route map, as it currently stands in the SW London area, be adjusted to one that would omit Balham as a CR2 station, but instead run from Clapham Junction, through a new CR2 station at Streatham - thereby providing the vital Southern Rail interchange required in SW London - and on to a reinstated CR2 station approaching from a south-easterly direction at Tooting Broadway - thereby providing the vital interchange in SW London with the Northern line. Of all of the three mainline stations in Streatham, Streatham station provides the ideal location for a CR2 station as it has the potential, through further expansion without considerable disruption, to develop to become a “strategic interchange” station to complement Balham station’s existing sole role in that capacity in SW London (please see below for further information in that regard). The area around Streatham station has experienced huge unpredicted population growth over the course of the past six years and this has been reflected also in a massive, and an equally unforeseen, surge in train usage. Streatham Action also recommends that the cost of building an additional CR2 station at Streatham, in addition to accommodating the additional journey time associated with the route curving round to Streatham, be offset by the CR2 route not incorporating a CR2 station location at King’s Road Chelsea but instead running directly from Victoria to Clapham Junction, thereby providing additional relief to both the Victoria and Northern lines. -

Balham 20 April 2019

Rail Accident Report Serious operational irregularity at Balham 20 April 2019 Report 01/2020 February 2020 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2020 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.gov.uk/raib. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Website: www.gov.uk/raib Derby UK DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Preface Preface The purpose of a Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) investigation is to improve railway safety by preventing future railway accidents or by mitigating their consequences. It is not the purpose of such an investigation to establish blame or liability. Accordingly, it is inappropriate that RAIB reports should be used to assign fault or blame, or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. RAIB’s findings are based on its own evaluation of the evidence that was available at the time of the investigation and are intended to explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner.