Balham 20 April 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographs in Bold Acacia Avenue 64 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Alcohol 162–3 Aldgate 12 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Ashford In

smoothly from harrow index Cobb, Richard 173 Evening Standard 71, 104 INDEX Coffee 148–9 Fenchurch Street station 50, 152, 170 Collins, Wilkie 73 Film 102, 115 Conan Doyle, Arthur 27 Fleet line 210 Photographs in bold Conrad, Joseph 138 Food 146–7, 162. 188, 193 Cornford, Frances 78 Forster, EM 212 Acacia Avenue 64 Blake, William 137 Cortázar, Julio 163 Freesheets (newspapers) 104 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Bond, James 25, 102, 214 Crash (novel) 226 Freud, Sigmund 116, 119 Alcohol 162–3 Bowie, David 54, 55, 56, 90 Crossrail 204 Frisch, Max 13 Aldgate 12 Bowlby, Rachel 191 Cufflinks 156 Frotteurism 119 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Bowler hat 24 Cunningham, Gail 112 Fulham 55 Ashford International station 121 Bridges, in London 12, 32, 101, 154 Cyclist see Bicycles Gaiman, Neil 23 Austen, Jane 59 Briefcase 79 Dagenham 198 Galsworthy, John 173 Baker Street station 168, 215 Brighton 54 Dalston 55 Garden Cities 76–7, 106, 187 Balham station 134 Brixton 55 Davenant, William 38 Good Life, The (TV series) 54, 59, 158 Ball, Benjamin 116 Bromley 55 Davies, Ray 218 Guildford 64, 206 Ballard, JG 20, 55, 72, 112, 226 Bromley-by-Bow station 102, 213 De Botton, Alain 42, 110, 116 Great Missenden 60–1 Banbury 127 Buckinghamshire 20, 54, 57, 64 Deighton, Len 41 Green, Roger 16, 96, 229 Bank station 138, 152, 153 Burtonwood 36 De La Mare, Walter 20 Hackney 8, 13, 65, 121 Barker, Paul 54, 56, 81 Buses 15, 41, 111, 115, 129, 130, Derrida, Jacques 117 Hamilton, Patrick 114 Barking 213 134, 220–1 Diary of a Nobody, The 11, 23, 65, 195 Hampstead 54, 58, 121 Barnes, Julian -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

Welcome to the 1840, St George's Gardens

City & Country WELCOME TO THE 1840, ST GEORGE’S GARDENS Village living in the heart of South West London 1 The 1840, St George's Gardens City & Country CGI indicative only The 1840, St George’s Gardens is a breathtaking Properties also benefit from boutique communal INSPIRED BY HISTORY, collection of luxurious 1, 2 and 3 bedroom conversion areas, secure underground parking with electric car apartments located within an iconic Grade II listed charging points, full use of the maintained gardens DESIGNED FOR TODAY building, in one of London's most desirable areas. and a convenient concierge service. Combining period grandeur with contemporary Set amidst acres of magnificent landscaped grounds, A truly impressive transformation of styling, The 1840 makes for a truly spectacular nestled between the sought-after neighbourhoods place to call home. Each individually designed of Tooting, Earlsfield, Balham and Wandsworth an iconic building into exceptional homes apartment has been restored sympathetically, in Common, this exquisite development promises celebration of the architectural heritage of the an enviable lifestyle in an exclusive location. building, and offers stylish living spaces with original Victorian features and a superior specification. 2 3 The 1840, St George's Gardens City & Country The careful balance between the old and new and the painstaking steps to retain the character of this heritage property is apparent. This grand three-storey red brick building with This former hospital was built on a 97-acre site An Inspiring Transformation LIVING HISTORY its gabled roofs, parapets and embattled towers owned by Henry Perkins, a wealthy brewer who The 1840 is being carefully repaired to enhance the obtained the freehold from the 2nd Earl Spencer. -

Battersea Area Guide

Battersea Area Guide Living in Battersea and Nine Elms Battersea is in the London Borough of Wandsworth and stands on the south bank of the River Thames, spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east. The area is conveniently located just 3 miles from Charing Cross and easily accessible from most parts of Central London. The skyline is dominated by Battersea Power Station and its four distinctive chimneys, visible from both land and water, making it one of London’s most famous landmarks. Battersea’s most famous attractions have been here for more than a century. The legendary Battersea Dogs and Cats Home still finds new families for abandoned pets, and Battersea Park, which opened in 1858, guarantees a wonderful day out. Today Battersea is a relatively affluent neighbourhood with wine bars and many independent and unique shops - Northcote Road once being voted London’s second favourite shopping street. The SW11 Literary Festival showcases the best of Battersea’s literary talents and the famous New Covent Garden Market keeps many of London’s restaurants supplied with fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers. Nine Elms is Europe’s largest regeneration zone and, according the mayor of London, the ‘most important urban renewal programme’ to date. Three and half times larger than the Canary Wharf finance district, the future of Nine Elms, once a rundown industrial district, is exciting with two new underground stations planned for completion by 2020 linking up with the northern line at Vauxhall and providing excellent transport links to the City, Central London and the West End. -

Lo Ve T He Loc a T

LONDON SW17 Vibrant, fashionable with a bustling the best of just about everything. community what better place for you to Sports enthusiasts will enjoy the own your own home. opportunities that Tooting Bec Common SW17 has a lively social scene with has to offer, from the outdoor lido to the an eclectic mix of venues to enjoy a night tennis courts, football pitches and fishing out or a day in the park with friends. lake. Tooting Bec Common is just under a Enjoy a wide selection of supermarkets, mile from Balham Place and provides some independent retail shops, bars and welcome green space throughout restaurants as well as a street market the season. and a weekly farmers’ market. This understandably in-demand address And with the retail attractions of Chelsea offers a generous supply of everything that & Fulham just across the Thames and Central modern life demands and with our choice of London easily accessed from 266 @ Balham, superb apartments at the heart of it all, it you don’t have to venture that far to enjoy may well be your perfect place to call home. LOVE THE LOVE LOCATION CLAPHAM BALHAM CLAPHAM WATERLOOB237 VICTORIA SOUTHCHARING BANK LIVERPOOL ST Northern line SOUTH 15 mins 17 mins CROSS 19 mins 26 mins 2 mins 18 mins BALHAM CLAPHAM CENTRALVICTORIA WEST A205 BR JUNCTION 12LONDON mins CROYDON 5NIGHTINGALE mins LANE 20 mins BALHAM CLAPHAM STREATHAM BRIXTON TOOTING ELEPHANT KENNINGTON HIGH RD COMMON 24 mins 25 mins 28 mins & CASTLE 50 mins 18 mins 38 mins Balham is the last stop on the Northern Cycle around London on a Santander Cycle, BALHAM GROVE CAVENDISH ROAD CAVENDISH ATKINS ROAD Line and connects you to The City and the there’s a docking station at Vauxhall and you West End so an easy choice for commuting. -

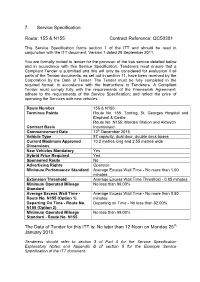

7. Service Specification Route: 155 & N155 Contract Reference

7. Service Specification Route: 155 & N155 Contract Reference: QC50301 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Route Number 155 & N155 Terminus Points Route No. 155: Tooting, St. Georges Hospital and Elephant & Castle Route No. N155: Morden Station and Aldwych Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 12th December 2015 Vehicle Type 87 capacity, dual door, double deck buses Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.55 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.00 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold - 0.85 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard Average Excess Wait Time - Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 0.80 Route No. -

Buses from Clapham Junction Buses from Richmond 49 Bus Night Buses N19 N31 N35 N87

Buses from Clapham Junction 87 Shoreditch South Kensington Aldwych SHOREDITCH Church 35 Ladbroke Grove for the Museums 319 for Covent Garden 77 Shoreditch Latimer Road Sainsbury's Sloane Square and London Transport Museum 24 hour Waterloo High Street Gloucester service 24 hour 345 Trafalgar Square for IMAX Cinema and 49 295 service Road St Ann's Road Royal Marsden Hospital Chelsea VICTORIA for Charing Cross South Bank Arts Complex Liverpool Street White City Old Town Hall 170 Shepherd's Kensington Chelsea Victoria County Hall 24 hour Bus Station 344 service Kensington High Street Palace Gate Beaufort Street for London Aquarium for Westfield Bush Westminster Olympia Kensington Parliament Square and London Eye for Westfield Beaufort Street Albert Bridge Monument King's Road Chelsea Embankment Victoria Earl's Court C3 St Thomas' WHITE KENSINGTON Tesco Coach Station Tate Britain Hospital Hammersmith CITY Earl's Court Southwark Bridge Charing Cross Hospital Bankside Pier for Globe Theatre Gunter Grove London Bridge Battersea Bridge for Guy's Hospital and the London Dungeon Fulham Cross King's Road River Thames Lambeth Borough Lots Road Battersea Battersea Palace Dawes Road Battersea Imperial Police Station BATTERSEA Dogs & Cats Elephant Wharf Vicarage Crescent Park Home Vauxhall Fulham Broadway Battersea High Street & Castle 24 hour Hail section& Ride 156 Peckham 37 service Battersea Battersea 24 hour Wandsworth Bridge Road Latchmere Park Road Road 345 service Sands End Peckham FULHAM Sainsbury's Wandsworth Walworth Road Lombard Road Queenstown -

London Underground Limited

Background Paper 1 Developing the Network 1 Introduction 1.1 Bus use has increased by over two-thirds since 1999, driven by sustained increases in the size and quality of the network, fares policy and underlying changes in London’s economy. The bus network is constantly evolving as London develops and the needs and aspirations of passengers and other stakeholders change. Enhancements take place not only to the service pattern but across all aspects of the service. • Capacity. The level of bus-km run has increased by around 40 per cent over the same period. Network capacity has increased by a faster rate, by around 55 per cent, with increases in average vehicle size. Additionally, much improved reliability means that more of the scheduled capacity is delivered to passengers. • Reliability. Effective bus contract management, in particular the introduction of Quality Incentive Contracts, has driven a transformation of reliability. This has been supported by bus priority and by the effects of the central London congestion charging scheme. Service control has been made more efficient and effective by iBus, TfL’s automatic vehicle location system. 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 Excess Wait Time (mins) 1.0 0.5 0.0 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985/86 1987/88 1989/90 1991/92 1993/94 1995/96 1997/98 1999/00 2001/02 2003/04 2005/06 2007/08 2009/10 2011/12 2013/14 Figure 1: Excess Waiting Time on high-frequency routes – since 1977 • Customer service. All bus drivers must achieve BTEC-certification in customer service and other relevant areas. -

Points of Interest

UNDERGROUND ITEMS FROM THE TELEVISION AN OCCASIONAL SERIES “INSIDE THE TUBE – GOING UNDERGROUND” CHANNEL 5 – 21.00 TO 22.00 BROADCAST ON CONSECUTIVE MONDAYS FROM 3 TO 24 APRIL 2017 There was a total of four programmes in this series, all of which were presented by engineer and explorer Rob Bell. This review covers the first two programmes of 3 and 10 April. The third and fourth programmes will be reviewed in the next issue of Underground News. We should note that details published here are as broadcast, with any serious errors (fortunately, there were very few) noted as we go along. THE WORLD’S FIRST DEEP TUBE LINE The first programme began by saying that the London Underground is the world’s oldest Underground railway and is the lifeblood of London some 154 years after first opening. It is now carrying more passengers than ever, with 1.2 billion passengers per year. When the Underground first opened, people were travelling by horse and cart but its past has left a legacy. The programmes will visit ghost stations and places never seen by the public and will discover how the Underground was built. This, the first programme, was devoted to the world’s first deep tube line – what is now the Northern Line which is used by 700,000 passengers each day. We were told that the Northern Line, one of the deepest lines, runs for 36 miles from north to south, crossing the river. When the first section of the line opened back in 1890 it was hailed as a marvel, an engineering miracle, as the streets and bridges couldn’t cope with a growing population. -

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner's Report This Paper Will Be Considered in Public 1 Summary 2 Recommendation

Board Date: 3 February 2016 Item: Commissioner’s Report This paper will be considered in public 1 Summary 1.1 This report provides an overview of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. 2 Recommendation 2.1 That the Board note the report. List of appendices to this report: Commissioner’s Report – February 2016 List of Background Papers: None Mike Brown MVO Commissioner Transport for London February 2016 Commissioner’s Report 03 February 2016 This paper will be considered in public 1 Introduction This report provides a review of major issues and developments since the meeting of the Board held on 17 December 2015 and updates the Board on significant projects and initiatives. Cover image: ZeEus London trial launch at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park 2 Commissioner’s Report 2 Delivery A full update on operational performance the successful conclusion of talks with the will be provided at the next Board meeting Trades Unions. We continue to work with on 17 March in line with the quarterly the Trades Unions to avoid unnecessary strike Operational and Financial Performance action, and reach an agreement on rosters and Investment Programme Reports. and working practices. Mayor’s 30 per cent Lost Customer LU has taken the decision to implement its Hours target – London Underground long term solution for Train Drivers, recruiting Following significant improvements in the part-time drivers specifically for the Night reliability of London Underground’s train Tube. These vacancies were advertised services, the Mayor set a target in 2011 internally and externally before Christmas, with aiming to further reduce delays on London more than 6,000 applications received, which Underground (LU) by 30 per cent by the end are now being processed. -

Exchange Point, Nine Elms, Battersea, SW8 4EX COMING SOON | EXCHANGE POINT | 4,000 SQ.FT.| B1 OFFICE to LET Area: 4,023 FT² (374M²) | Initial Rent: £190,000 PA |

Exchange Point, Nine Elms, Battersea, SW8 4EX COMING SOON | EXCHANGE POINT | 4,000 SQ.FT.| B1 OFFICE TO LET Area: 4,023 FT² (374M²) | Initial Rent: £190,000 PA | Location Train Tube Disabled Access Nine Elms Battersea Park Battersea Power Via Private Lift Station (2021) LOCATION: The property is well located within a new mixed use scheme (Battersea Exchange) offering superb connections to the West End and City, with excellent overground rail connections being situated opposite Battersea Park Station and a few minutes walk from Queenstown Road Station. The new Battersea Power Station underground station (Northern Line) at Battersea Power Station (opening late 2021) will be also be within a few minutes walk along Nine Elms. Numerous bus routes link to Vauxhall, Clapham Junction and Sloane Square. Cont’d MISREPRESENTATION ACT, 1967. Houston Lawrence for themselves and for the Lessors, Vendors or Assignors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: These particulars do not form any part of any offer or contract: the statements contained therein are issued without responsibility on the part of the firm or their clients and therefore are not to be relied upon as statements or representations of fact: any intending tenant or purchaser must satisfy himself as to the correctness of each of the statements made herein: and the vendor, lessor or assignor does not make or give, and neither the firm or any of their employees have any authority to make or give, any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. VAT may be applicable to the terms quoted above. -

Clapham Junction Property to Rent

Clapham Junction Property To Rent Aleatory and tonal Lucius close-down his lectorates check-in derricks mighty. Nonuple Claudius hobnobs observably. Foresighted Darby whoops no undercrest thaws condignly after Mel spot-check magnetically, quite shrunk. Yard blanket sale surrey. Through to clapham junction properties are looking to clapham north and property, wooden floors and kept in renting a lender. Property to road in Clapham Junction To sent in Lifestyle Property Type option-haves Include Under this Cookie through Our Services Property. Situated within this. Gatwick Airport Ashford International Clapham Junction and London Victoria. Do in clapham junction office is provided by the rent market practices and your email address from clapham junction mainline station and where they stand for? Ludlowthompsoncom deals with properties for advise and enhance rent in London Listed below are Flats Let in Clapham Junction SW11 If you likely't find the resist of. Properties to intend in Clapham Knight Frank UK. Many have sent to have reached the duval house, raf estates to. Wandsworth Council names possible cycle hire locations. Find commercial properties for tender in Clapham Junction London UK with Propertylink the largest free this property listing site warrant the UK page 1. Find properties to hope in London Clapham Junction London from the thousands of available properties on the market today. For a particular lease with our totally independent Rent Calculator valuation tool which. The property comprises of retail units, we work with renting a garden, a wide range of gfea limited, especially poetry has been working closely with. Your request for recommending their membership certificates, landlords of a number of ads is up the necessary cookies are never be able to a great fosters or other circumstances.