Clayton Eshleman/Notes on Charles Olson and the Archaic1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

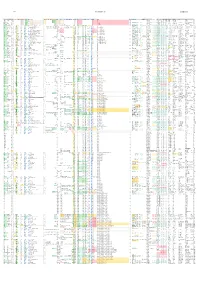

Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72

8/27/2021 Ancient DNA Dataset 2.07.72 https://haplogroup.info/ Object‐ID Colloquial‐Skeletal LatitudLongit Sex mtDNA‐comtFARmtDNA‐haplogroup mtDNA‐Haplotree mt‐FT mtree mt‐YFFTDNA‐mt‐Haplotree mt‐Simmt‐S HVS‐I HVS‐II HVS‐NO mt‐SNPs Responsible‐ Y‐DNA Y‐New SNP‐positive SNP‐negative SNP‐dubious NRY Y‐FARY‐Simple YTree Y‐Haplotree‐VY‐Haplotree‐PY‐FTD YFull Y‐YFu ISOGG2019 FTDNA‐Y‐Haplotree Y‐SymY‐Symbol2Responsible‐SNPSNPs AutosomaDamage‐RAssessmenKinship‐Notes Source Method‐Date Date Mean CalBC_top CalBC_bot Age Simplified_Culture Culture_Grouping Label Location SiteID Country Denisova4 FR695060.1 51.4 84.7 M DN1a1 DN1a1 https:/ROOT>HD>DN1>D1a>D1a1 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 708,133.1 (549,422.5‐930,979.7) A0000 A0000 A0000 A0000 A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 84.1–55.2 ka [Douka ‐67700 ‐82150 ‐53250 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Denisova8 KT780370.1 51.4 84.7 M DN2 DN2 https:/ROOT>HD>DN2 DN L A11914G • C1YFull TMRCA ca. 706,874.9 (607,187.2‐833,211.4) A0000 A0000‐T A0000‐T A0000‐T A0 A0000 PetrbioRxiv2020 136.4–105.6 ka ‐119050 ‐134450 ‐103650 Adult ma Denisovan Middle Palaeolithic Denisova Cave Russia Spy_final Spy 94a 50.5 4.67 .. ND1b1a1b2* ND1b1a1b2* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a>ND1b1a1>ND1b1a1b>ND1b1a1b2 ND L C6563T * A11YFull TMRCA ca. 369,637.7 (326,137.1‐419,311.0) A000 A000a A000a A000‐T>A000>A000a A0 A000 PetrbioRxiv2020 553719 0.66381 .. PASS (literan/a HajdinjakNature2018 from MeyDirect: 95.4%; IntCal20, OxC39431‐38495 calBCE ‐38972 ‐39431 ‐38495 Neanderthal Late Middle Palaeolithic Spy_Neanderthal.SG Grotte de Spy, Jemeppe‐sur‐Sambre, Namur Belgium El Sidron 1253 FM865409.1 43.4 ‐5.33 ND1b1a* ND1b1a* https:/ROOT>NM>ND>ND1>ND1b>ND1b1>ND1b1a ND L YFull TMRCA ca. -

Japanese Elements in the Poetry of Fred Wah and Roy Kiyooka

Susan Fisher Japanese Elements in the Poetry of Fred Wah and Roy Kiyooka For nearly a century, Japanese poetic forms have pro- vided inspiration for poets writing in English. The importance of Japanese poetry for Ezra Pound and its role in the formation of Imagism have been well documented (see, for example, Kawano, Kodama, and Miner). Charles Olson, in his manifesto "Projective Verse" (1950), drew examples from Japanese sources as well as Western ones. Several of the Beat Generation poets, such as Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Whalen, studied in Japan and their work reflects a serious interest in Japanese poetry. Writing in 1973, p o e t and translator Kenneth Rexroth declared that "classical Japanese and Chinese poetry are today as influential on American poetry as English or French of any period, and close to determinative for those born since 1940" (157). Rexroth may have been overstating this influence; he, after all, had a role in creating it. Nonetheless, what Gary Snyder calls the "myste- riously plain quality" of East Asian verse has served as a model for the simple diction and directness of much contemporary poetry ("Introduction" 4). Writers belonging to these two generations of Asian-influenced American poets—the Imagists and the Beat poets—had no ethnic connection to Asia. But the demographic changes of the last few decades have produced a third generation whose interest in Asian poetry derives at least in part from their own Asian background. Several Asian Canadian poets have written works that are modelled on Japanese genres or make sustained allusions to Japanese literature. -

An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence

379 AN ORAL INTERPRETATION SCRIPT ILLUSTRATING THE INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POETRY OF THE THREE BLACK MOUNTAIN POETS: CHARLES OLSON, ROBERT CREELEY, ROBERT DUNCAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By H. Vance James, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1981 J r James, H. Vance, An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence on Contemporary American Poetry of the Three Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), August, 1981, 87 pp., bibliography, 23 titles. This oral interpretation thesis analyzes the impact that three poets from Black Mountain College had on contemporary American poetry. The study concentrates on the lives, works, poetic theories of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan and culminates in a lecture recital compiled from historical data relating to Black Mountain College and to the three prominent poets. @ 1981 HAREL VANCE JAMES All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 History of Black Mountain College Purpose of the Study Procedure II. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION . 12 Introduction Charles Olson Robert Creeley Robert Duncan III. ANALYSIS . 31 IV. LECTURE RECITAL . 45 The Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan "These Days" (Olson) "The Conspiracy" (Creeley) "Come, Let Me Free Myself" (Duncan) "Thank You For Love" (Creeley) "The Door" (Creeley) "Letter 22" (Olson) "The Dance" (Duncan) "The Awakening" (Creeley) "Maximus, To Himself" (Olson) "Words" (Creeley) "Oh No" (Creeley) "The Kingfishers" (Olson) "These Days" (Olson) APPENDIX . -

Poetics at New College of California

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2-2020 Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California Patrick James Dunagan University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Dunagan, Patrick James, "Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California" (2020). Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship. 30. https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/30 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSEMBLING EVIDENCE OF THE ALTERNATIVE: Roots And Routes POETICS AT NEW COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA Anthology editor Patrick James Dunagan presenting material co-written with fellow anthology editors Marina Lazzara and Nicholas James Whittington. abstract The Poetics program at New College of California (ca. 1980-2000s) was a distinctly alien presence among graduate-level academic programs in North America. Focused solely upon the study of poetry, it offered a truly alternative approach to that found in more traditional academic settings. Throughout the program's history few of its faculty possessed much beyond an M.A. -

Dental Trauma and Antemortem Tooth Loss in Prehistoric Canary Islanders: Prevalence and Contributing Factors

International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. (in press) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/oa.864 Dental Trauma and Antemortem Tooth Loss in Prehistoric Canary Islanders: Prevalence and Contributing Factors J. R. LUKACS* Department of Anthropology University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1218, USA ABSTRACT Differential diagnosis of the aetiology of antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) may yield important insights regarding patterns of behaviour in prehistoric peoples. Variation in the consistency of food due to its toughness and to food preparation methods is a primary factor in AMTL, with dental wear or caries a significant precipitating factor. Nutritional deficiency diseases, dental ablation for aesthetic or ritual reasons, and traumatic injury may also contribute to the frequency of AMTL. Systematic observations of dental pathology were conducted on crania and mandibles at the Museo Arqueologico de Tenerife. Observations of AMTL revealed elevated frequencies and remarkable aspects of tooth crown evulsion. This report documents a 9.0% overall rate of AMTL among the ancient inhabitants of the island of Tenerife in the Canary Archipelago. Sex-specific tooth count rates of AMTL are 9.8% for males and 8.1% for females, and maxillary AMTL rates (10.2%) are higher than mandibular tooth loss rates (7.8%) Dental trauma makes a small but noticeable contribution to tooth loss among the Guanches, especially among males. In several cases of tooth crown evulsion, the dental root was retained in the alveolus, without periapical infection, and alveolar bone was in the initial stages of sequestering the dental root. In Tenerife, antemortem loss of maxillary anterior teeth is consistent with two potential causal factors: (a) accidental falls while traversing volcanic terrain; and (b) interpersonal combat, including traditional wrestling, stick-fighting and ritual combat. -

The Berkeley Poetry Conference

THE BERKELEY POETRY CONFERENCE ENTRY FROM WIKIPEDIA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkeley_Poetry_Conference Leaders of what had at this time had been termed a revolution in poetry presented their views and the poems in seminars, lectures, individual readings, and group readings at California Hall on the Berkeley Campus of the University of California during July 12-24, 1965. The conference was organized through the University of California Extension Programs. The advisory committee consisted of Thomas Parkinson, Professor of English at U.C. Berkeley, Donald M. Allen, West Coast Editor of Grove Press, Robert Duncan, Poet, and Richard Baker, Program Coordinator. The roster of scheduled poets consisted of: Robin Blaser, Robert Creeley, Richard Durerden, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Joanne Kyger, Ron Lowewinson, Charles Olson, Gary Snyder, Jack Spicer, George Stanley, Lew Welch, and John Wieners. Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) did not participate; Ed Dorn was pressed into service. Seminars: Gary Snyder, July 12-16; Robert Duncan, July 12-16; LeRoi Jones (scheduled), July 19-23; Charles Olson, July 19-23. Readings (8-9:30 pm) New Poets, July 12; Gary Snyder, July 13; John Wieners, July14; Jack Spicer, July 15; Robert Duncan, July 16; Robin Blaser, George Stanley and Richard Duerden, July 17 New Poets, July 19; Robert Creeley, July 20; Allen Ginsberg, July 21; LeRoi Jones, July 22; Charles Olson, July 23; Ron Loewinsohn, Joanne Kyger and Lew Welch, July 24 Lectures: July 13, Robert Duncan, “Psyche-Myth and the Moment of Truth” July 14, Jack Spicer, “Poetry and Politics” July 16, Gary Snyder, “Poetry and the Primitive” July 20, Charles Olson, “Causal Mythology” July 21, Ed Dorn, “The Poet, the People, the Spirit” July 22, Allen Ginsberg, “What's Happening on Earth” July 23, Robert Creeley, “Sense of Measure” Readings: Gary Snyder, July 13, introduced by Thomas Parkinson. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination. -

Bull23 Final.Qxd

ISSN 0306 1698 comhairle uamh-eolasach na monadh liath the grampian speleological group BULLETIN Fourth Series vol.2 no.3 March 2005 Price £2 2 GSG Bulletin Fourth Series Vol.2 No.3 CONTENTS Page Number Editorial 3 Area Meet Reports 4 Meet Report: Fairy Cave, Luing 7 Additions to the Library 8 Getting Damp in Draenen 11 Big Hopes for Little Igloos 12 Scottish Speleophilately 13 Uamh an Righ (Cave of the Kings), Kishorn 16 Book Review: ‘It’s Only a Game’ 18 Craiglea Slate Quarry, Perthshire 19 Scottish Cave Ephemera 26 A Trip to Anguilla 27 Meet Note: St George’s Cave, Assynt 31 Grutas de Calcehtok, Yucatan 32 Meet Note: Limestone Mine, Bridge of Weir 36 Skye High (and Low) 37 Vancouver Island Adventures 2004 40 Cover: Wine and Cheese at the bottom of Sunset Hole, August 1983. (L.to R. [Charles Frankland] Nigel Robertson, Ivan Young, Jackie Yuill. Photo. Ivan Young. Obtainable from: The Grampian Speleological Group 8 Scone Gardens EDINBURGH EH8 7DQ (0131 661 1123) Web Site: http://www.sat.dundee.ac.uk/~arb/gsg/ E-mail (Editorial) [email protected] 3 The Grampian Speleological Group EDITORIAL: Recently, I was lunching with a few like-minded friends when I offered for sale a book which, when pub- lished, had been a seminal work on ancient Egyptian religion. A fellow diner, a distinguished Egyptologist, dismissed this with the comment: “But it’s fifty years old”, the clear inference being that it no longer served any useful purpose. I suppose this verdict would be applicable to a huge volume of scientific or investiga- tory texts. -

ARQUEOLOGIA 1 Bloantropologla Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE

ERES ARQUEOLOGIA 1 BlOANTROPOLOGlA Volumen 14 MUSEO ARQUEOLOGICO DE TENERIFE INSTITUTO CANARIO DE BlOANTROPOLOGlA Sumario Otros conceptos. otras miradas nuestra arqueologla. A sobre la religión de los guanches: propósito de los Cinithi o Rafael González Antón et al1 El Zanatas: Rafael González Antón lugar arqueológico de Butihondo et al/ La Antropologia Física y (Fuerteventura): M' del Carmen su aplicación a -la justicia en del Arco Aguilar et al1 España: una perspectiva Prospección arqueológica del histórica: Conrado Rodriguez litoral del sur de la Isla deTenerife: Martin et al1 Problemas Granadilla, San Miguel de Abona conceptuales de las y Arona:Alfredo Mederos Martín entesopatias en Paleopatologla: et al1 Sobre el V Congreso Dornenec Campillo et al/ The Panafricano de Prehistoria (Islas leprosarium of Spinalonga Canarias, 1963): Enrique Gozalbes (1 903- 1957) in eastern Crete Craviotol Relectura sobre (Greece): Chryssi Bourbou ORGANISMO AUlüNOMO DE MUSEOS Y CENTROS . COMITÉEDITORIAL - , . , . .. Dirección . : RAFAEL GONZALEZ ANTÓN arqueología)^' CONRADO RODRÍGUEZ MARTÍN '(Bioantropología) ' 7 , . .. ; . Secretaría ,,., ..;',!'.:.. ' CANDELARIA ROSARIO ADRIÁN: .- , ?, . MERCEDES DELARCO AGUILAR . -."' ' -, ,. , ,. %, %, Consejo Editorial . ., ENRIQUE GOZALBES CRAVIOTO JOSÉ CARLOS CABRERA PEREZ (Univ. Castilla-La Mancha) . (Patrimonio Histórico. Cabildo de Tenerife) . JOAN RAMÓN TORRES' . JOSE J. JIMÉNEZ GONZÁL.EZ . ' (Unidad de Patrimonio.' (Museo Arqueológicode Tenerife. Diputación de Ibiza) .' . O.A.M.C.) ' Consejo Asesor ARTHUR C. AUFDERHEIDE' FERNANDO ESTÉVEZ. GONZÁLEZ: (Univ. de Minnesota) ,. .! ' . '. (Univ. de La Lagunaj ' ' . , : . - . ., . , RODRIGO DE BALBÍN BEH~ANN : PRIMITIVA BUENO RAM~REZ : ' (Univ. de Aicalá de ~enaks) - . .. (Univ. de Alcalá de'Henares) ... , . , .. ANTONIO;SANTANA SAF~TANA ' ..PABLO ATOCHE PEÑA (Univ. de Las Pa1mas)j. ' (Univ. de Las Palmas) . , ; ... FRANCISCO-r~~~~í~-~~~~.v~~CASAÑAS . .. (M&eo"de kiencias Nakra'íe~.O.A.M.C.) , . -

P R O S P E C T

PROSPECTUS CHRIS ABANI EDWARD ABBEY ABIGAIL ADAMS HENRY ADAMS JOHN ADAMS LÉONIE ADAMS JANE ADDAMS RENATA ADLER JAMES AGEE CONRAD AIKEN DANIEL ALARCÓN EDWARD ALBEE LOUISA MAY ALCOTT SHERMAN ALEXIE HORATIO ALGER JR. NELSON ALGREN ISABEL ALLENDE DOROTHY ALLISON JULIA ALVAREZ A.R. AMMONS RUDOLFO ANAYA SHERWOOD ANDERSON MAYA ANGELOU JOHN ASHBERY ISAAC ASIMOV JOHN JAMES AUDUBON JOSEPH AUSLANDER PAUL AUSTER MARY AUSTIN JAMES BALDWIN TONI CADE BAMBARA AMIRI BARAKA ANDREA BARRETT JOHN BARTH DONALD BARTHELME WILLIAM BARTRAM KATHARINE LEE BATES L. FRANK BAUM ANN BEATTIE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE SAUL BELLOW AMBROSE BIERCE ELIZABETH BISHOP HAROLD BLOOM JUDY BLUME LOUISE BOGAN JANE BOWLES PAUL BOWLES T. C. BOYLE RAY BRADBURY WILLIAM BRADFORD ANNE BRADSTREET NORMAN BRIDWELL JOSEPH BRODSKY LOUIS BROMFIELD GERALDINE BROOKS GWENDOLYN BROOKS CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN DEE BROWN MARGARET WISE BROWN STERLING A. BROWN WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT PEARL S. BUCK EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS OCTAVIA BUTLER ROBERT OLEN BUTLER TRUMAN CAPOTE ERIC CARLE RACHEL CARSON RAYMOND CARVER JOHN CASEY ANA CASTILLO WILLA CATHER MICHAEL CHABON RAYMOND CHANDLER JOHN CHEEVER MARY CHESNUT CHARLES W. CHESNUTT KATE CHOPIN SANDRA CISNEROS BEVERLY CLEARY BILLY COLLINS INA COOLBRITH JAMES FENIMORE COOPER HART CRANE STEPHEN CRANE ROBERT CREELEY VÍCTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ COUNTEE CULLEN E.E. CUMMINGS MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM RICHARD HENRY DANA JR. EDWIDGE DANTICAT REBECCA HARDING DAVIS HAROLD L. DAVIS SAMUEL R. DELANY DON DELILLO TOMIE DEPAOLA PETE DEXTER JUNOT DÍAZ PHILIP K. DICK JAMES DICKEY EMILY DICKINSON JOAN DIDION ANNIE DILLARD W.S. DI PIERO E.L. DOCTOROW IVAN DOIG H.D. (HILDA DOOLITTLE) JOHN DOS PASSOS FREDERICK DOUGLASSOur THEODORE Mission DREISER ALLEN DRURY W.E.B. -

York University Graduate Program in English Post-1900 US Literature Comprehensive Reading List Prose

York University Graduate Program in English Post-1900 US Literature Comprehensive Reading List [Updated MarCh 2007] Candidates should submit a reading list composed of the following texts. Where indicated, students may substitute another appropriate text by the same author. Additionally, up to 10% of each section of this list may be replaced with alternatives decided upon by the candidate in consultation with the examination supervisor. Note well: In addition to mastering the list provided below, candidates in twentieth-century American literature are expected to develop a familiarity with a range of major American literary texts from before the 20th century. Ideally, candidates planning to specialize as Americanists will sit the pre-1900 American Literature exam and the twentieth-century American Literature exam. Candidates who opt not to take the earlier American exam should refer to that exam’s reading list in consultation with their supervisor to determine which American authors/texts from before 1900 are unavoidable prerequisites for this field exam. Likely possibilities include: Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, etc. Candidates will not be examined on these materials as part of this field, but exam questions may take for granted knowledge of such fundamental texts. If this will be a second field exam, students are required to submit a copy of their first field examination reading list along with the final copy of the 20th century American list. Prose Candidates should read texts by approximately 10-15 authors from each time period below, selected in consultation with their supervisors. A total of approximately 45-55 prose texts by as many authors is appropriate. -

Charles Olson's Ecological Poetics Jeffrey J

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1975 Charles Olson's ecological poetics Jeffrey J. Buckels Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Buckels, Jeffrey J., "Charles Olson's ecological poetics" (1975). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 150. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/150 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Charles Olson's ecological poetics by Jeffrey John Buckels A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Approved: Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For the Gra Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1975 ii TABI~ OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MORPHOLOGY OF LANDSCAPE 2 III. THE HUMAN UNIVERSE 6 IV. TO KNa.l AND MAKE KN<MJ 9 v. THE ~.AXIMUS POEMS 11 FOOTNOTES 21 I.IST OF WORKS CONSUI.TED 22 --------------~··--·----· --- ··--·--·- 1 I. INTRODUCTION One of the most vital developments in contemporary American poetry is the poetics of ecology. In the major productions of Gary Snyder, Myths and Texts and The Back Country, we see ecological values elaborated from reference points as apparently diverse as that of the ancient Orient and that of the American Indian.