Crossing Borders and Singing About Erotic Desires in Bhawaiyaa Folk Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal Para)

CHAPTER- III Formation of the Heterogeneous Society in Western Assam (Goal para) Erstwhile Goalpara district of Western Assam has a unique socio-cultural heritage of its own, identified as Goalpariya Society and Culture. The society is a heterogenic in character, composed of diverse racial, ethnic, religious and cultural groups. The medieval society that had developed in Western Assam, particularly in Goalapra region was seriously influenced by the induction of new social elements during the British Rule. It caused the reshaping of the society to a fully heterogenic in character with distinctly emergence of new cultural heritage, inconsequence of the fusion of the diverse elements. Zamindars of Western Assam, as an important social group, played a very important role in the development of new society and cufture. In the course of their zamindary rule, they brought Bengali Hidus from West Bengal for employment in zamindary service, Muslim agricultural labourers from East Bengal for extension of agricultural field, and other Hindusthani people for the purpose of military and other services. Most of them were allowed to settle in their respective estates, resulting in the increase of the population in their estate as well as in Assam. Besides, most of the zamindars entered in the matrimonial relations with the land lords of Bengal. As a result, we find great influence of the Bengali language and culture on this region. In the subsequent year, Bengali cultivators, business community of Bengal and Punjab and workers and labourers from other parts of Indian subcontinent, migrated in large number to Assam and settled down in different places including town, Bazar and waste land and char areas. -

Tribal Religion of Lower Assam of North East India

TRIBAL RELIGION OF LOWER ASSAM OF NORTH EAST INDIA 1HEMANTA KUMAR KALITA, 2BHANU BEZBORA KALITA 1Associate Professor, Dept. of Philosophy, Goalpara College, 2Associate Professor, Dept of Assamese, Goalpara College E-mail: [email protected] Abstract - Religion is very sensitive issue and naturally concerned with the sentiment. It is a matter of faith and made neither through logical explanation nor scientific verification. That Religion from its original point of view was emerged as the basic needs and tools of livelihood. Hence it was the creation of human being feeling wonderful happenings bosom of nature at the early stage of origin of religion. It is not exaggeration that tribal people are the primitive bearer of religious belief. However religion for them was not academically explored rather it was regarded as the matter of reverence and submission. If we regard religion from the original point of view the religion then is not discussed under the caprice of ill design.. To think about God, usually provides no scientific value as it is not a matter of verification and material pleasant. Although to think about God or pray to God is also not worthless. Pessimistic and atheistic ideology though not harmful to human society yet the reverence and faith towards God also minimize the inter religious hazards and conflict. It may help to strengthen spirituality and communicability with others. Spiritualism renders a social responsibility in true sense which helps to understand others from inner order of heart. We attempt to discuss some tribal religious festivals along with its special characteristics. Tribal religion though apart from the general characteristic feature it ushers natural gesture and caries tolerance among them. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol 6 Issue 10 July 2017 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Ecaterina Patrascu A R Burla College, India Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Kamani Perera Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Regional Editor Dr. T. Manichander Advisory Board Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Mabel Miao Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Lanka Xiaohua Yang Ruth Wolf Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University Walla, Israel Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Jie Hao Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Sydney, Australia University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Anna Maria Constantinovici May Hongmei Gao University of Essex, United Kingdom AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Kennesaw State University, USA Romona Mihaila Marc Fetscherin Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Rollins College, USA Spiru Haret University, Romania Liu Chen Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. Shinde Islamic Azad University buinzahra Director, Isara Institute of Management, New Bharati Vidyapeeth School of Distance Branch, Qazvin, Iran Delhi Education Center, Navi Mumbai Titus Pop Salve R. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: a Study of Social and Religious Perspective

British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 2(3), 60-72, 2020 Publisher homepage: www.universepg.com, ISSN: 2663-7782 (Online) & 2663-7774 (Print) https://doi.org/10.34104/bjah.020060072 British Journal of Arts and Humanities Journal homepage: www.universepg.com/journal/bjah Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: A Study of Social and Religious Perspective Ruksana Karim* Department of Music, Faculty of Arts, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. *Correspondence: [email protected] (Ruksana Karim, Lecturer, Department of Music, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh) ABSTRACT This paper describes how South Asian folk music figured out from the ancient era and people discovered its individual form after ages. South Asia has too many colorful nations and they owned different culture from the very beginning. Folk music is like a treasure of South Asian culture. According to history, South Asian people established themselves here as a nation (Arya) before five thousand years from today and started to live with native people. So a perfect mixture of two ancient nations and their culture produced a new South Asia. This paper explores the massive changes that happened to South Asian folk music which creates several ways to correspond to their root and how they are different from each other. After many natural disasters and political changes, South Asian people faced many socio-economic conditions but there was the only way to share their feelings. They articulated their sorrows, happiness, wishes, prayers, and love with music, celebrated social and religious festivals all the way through music. As a result, bunches of folk music are being created with different lyric and tune in every corner of South Asia. -

Chapter 3 Assam

Chapter 3 Assam Udayon Misra 1. The Ahom Period (1328-1826) The impression has long sought to be created that the “North-East” is a landlocked area and that its geographical isolation is a major factor contributing to its economic backwardness. Not to speak of the pre-Ahom period when Assam, made up primarily of the Brahmaputra Valley, had quite an active interaction with the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, even under the Ahom rulers (1328-1826) who were known for their closed-door approach, there was active trade between Assam and her western neighbours, Bengal and Bihar as also with Bhutan, Tibet and Myanmar. Describing the kingdom of Assam during the height of Ahom rule in the seventeenth century, the historian S.K.Bhuyan states: “The kingdom of Assam, as it was constituted during the last 140 years of Ahom rule, was bounded on the north by a range of mountains inhabited by the Bhutanese, Akas, Daflas and Abors; on the east, by another line of hills people by the Mishmis and the Singhphos; on the south, by the Garo, Khasi, Naga and Patkai hills; on the west, by the Manas or Manaha river on the north bank, and the Habraghat Pargannah on the south in the Bengal district of Rungpore. The kingdom where it entered from Bengal commenced with the Assam Choky (gate) on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, opposite Goalpara; while on the south bank it commenced from the Nagarberra hill at a distance of 21 miles to the east of Goalpara. “The kingdom was about 500 miles in length, with an average breadth of 60 miles. -

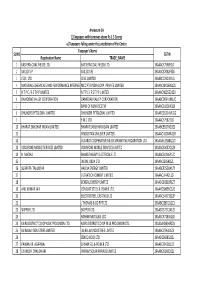

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020

Editorial Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020 Applied Sciences Editorial Office MDPI AG, St. Alban-Anlage 66, 4052 Basel, Switzerland Peer review is the driving force of journal development, and reviewers are gatekeepers who ensure that Applied Sciences maintains its standards for the high quality of its pub- lished papers. Thanks to the cooperation of our reviewers, in 2020, the median time to first decision was 15 days and the median time to publication was 35 days. The editors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the following reviewers for their precious time and dedication, regardless of whether the papers were finally published: Aamir, Muhammad Abdeljaber, Osama Aarniovuori, Lassi Abdelkader, Amr Aasa, Ulrika Abdelkefi, Abdessattar Aase, Reyes Abdellatef, Mohammed Abad, Begoña Abdellatif, Mohamed Abah, Obinna Abdelmaksoud, Ahmed Abainia, Kheireddine Abdelrahman, Mohamed Abalasei, Aurelia Beatrice Abdelrazec, Ahmed H. M. Abanteriba, Sylvester Abdelsalam, Mahmoud Abarca-Sos, Alberto Abdelsalam, Sara I. Abaspur Kazerouni, Iman Abdelwahed, Sameh Abate, Giada Abdi, Ghasem Abate, Lorenzo Abdo, Ahmad Abatzoglou, Nicolas Abdo, Peter Citation: Applied Sciences Editorial Abawajy, Jemal Abdul-Aziz, Ali Office. Acknowledgment to Abaza, Osama A. Abdulhammed, Razan Reviewers of Applied Sciences in 2020. Abbas, Farhat Abdulkhaleq, Ahmed Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1108. https:// Abbasi Layegh, Mahmood abdullah, Abu Yousuf Md doi.org/10.3390/app11031108 Abbasi, Hamid Abdullah, Oday Ibraheem Abbasi, Ubaid Abdullah, Tariq Published: 26 January 2021 Abbasnia, Arash Abdulmajeed, Wael Abbaspour, Aiyoub Abdur, Rahim Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neu- Abbatangelo, Marco Abed, Eyad H. tral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- Abbes, Boussad Abedi, Reza tional affiliations. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 8, Issue, 11, pp.41932-41942, November, 2016 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE THE FOLK SONGS SUNG IN ASSAM WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FOLKSONGS EXCLUSIVELY SUNG BY ASSAMESE WOMEN *Nabamita Das, M. S. Research Scholar, Department of Folklore Research, Gauhati University, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Assamese folksongs have been originated from the Tribal culture of Assam and it collectively expresses the inherent Article History: traditional and cultural dimensions of Assam. The folksongs of Assam may be devided into various categories such as rd Received 03 August, 2016 Songs of religious and devotional content like Sādāsivār Nāām, Dûrgāā Gôsāānir Nāām, Lākshmi Devir Nāām, Ãāi Received in revised form Nāām, Dèhbichāārār Gēēt, Ãājān Fākirār Gēēt etc, Songs of ceremonies and festivals like Õjāā-pāāli, Mādān–Kāām 15th September, 2016 Pujā, Kāti pujā, Jorā Nāām, Khichāā Gēēt, Bihu songs and the like, Songs of love and yearning like Bhāwāiyāā and Accepted 06th October, 2016 Chātkāā, Môishāli and Māût songs, Bārāmāhi songs, Lullaby and nursery songs like Nisukāni Gēēt and Dhāāināām, Published online 30th November, 2016 Songs of jest and humour song like Tāāmul Chôrār Gēēt, Chāāh-purāānar Gēēt etc, Ballad and other narrative songs like Bārphûkānār Gēēt, Mānirām Dèwānār Gēēt, Hārādāttā-Birādāttār Gēēt, Jānāābhārur gēēt, Kāmālkuwārir gēēt, Tezimolār Gēēt and the like, These are the different types of folksongs sung in Assam. But the folksongs sung exclusively Key words: by women are- Nisukāni Gēēt, Hûdûmpûjār Gēēt, Aulāā Pujā, Suwāguritolā Gēēt, Biyāānāām, Jengbihu, Nisukāni gēēt , Dhāaināām, Ãāināām, Apesārāā sābāhār Nāām, Goalpariyāā Lokgēēt etc. -

Sal Timber Trade in Goalpara District During Colonial Period

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 The NEHU Journal, Vol XIV, No. 2, July-December 2016, pp.87-99 Sal Timber Trade in Goalpara District During Colonial Period JAYSAGAR WARY & OINAM RANJIT SINGH* Abstract Sal (Soria Robusta), a hard wood tree, was found extensively in Goalpara forest of Assam. Before the establishment forest department in Assam, the Sal trees were exploited by the Zamindars and private traders for boat making and house constructions. The British India earned huge money from the selling of Sal timber of Goalpara forest division. The Railway line construction in Assam also compelled the extraction of Sal timber. Keywords: Goalpara forest, Sal timber, Railways, Trade and Communication. he Sal forests became important resources of Goalpara district during the colonial period which provided huge revenue to the British India. TBefore the establishment of forest department in Assam, the Sal trees of Goalpara region were exploited by the Zamindars and private traders for house construction, boat making and exporting to the other countries. The timber traders came by boats from Dacca and Mymensingh during rainy season to buy up Sal timber in Goalpara forest.1 The timber was tied with boats and then floated down to the port of Narayanganj near Dhaka. The Sal forest of Porbatjhora and Khuntaghat Parganas were exploited by the Daffadars and timber lumbers of Bengal.2 As Buchanan Hamilton reported: Merchants of Goalpara usually export to the low country from the forests of Howraghat and Mechpara about 1500 canoes in the year...[T]he timber was floated down numerous rivers which included the Ai and Manas, from the Dooar region and also from Nepal and Bhutan, towards the southern ports like Fakirganj.3 ____________________________________________________________________ *Jaysagar Wary ([email protected]) and Oinam Ranjit Singh are teaching in the Department of History, Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Assam. -

2. Introduction to Art & Creative Education

õ∂±Ôø˜fl¡ ø˙鬱1 øάõ≠혱 ¬Û±Í¬…Sê˜ DIPLOMA IN ELEMENTARY EDUCATION (D. El. Ed.) fl¡˘± ’±1n∏ ¸‘Ê√Ú±Rfl¡ ø˙鬱1 ˝√√±Ó¬¬Û≈øÔ HANDBOOK ON ART & CREATIVE EDUCATION fl‘¡¯ûfl¡±ôL ¸øµÕfl¡ 1±øÊ√…fl¡ ˜≈Mê√ ø¬ıù´ø¬ı√…±˘˚˛ KRISHNA KANTA HANDIQUI STATE OPEN UNIVERSITY Handbook on Art & Creative Education 1 HANDBOOK PREPARATION TEAM Content Contributors Translator Sri Kishor Kumar Das, DIET, Morigaon Geetanjali Medhi, KKHSOU Dr. Mousumi Deka, Royal Global University, Guwahati Editors Language (Ass) : Dr. Neeva Rani Phukan, Dept. of Assamese, KKHSOU Language (Eng) : Pallavi Gogoi, Dept. of English, KKHSOU Format : Devajani Duarah, Dept. of Teacher Education, KKHSOU Dopati Choudhury, Dept. of Teacher Education, KKHSOU Co-ordinator : Devajani Duarah, KKHSOU June, 2017 © Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University This ''Handbook on Art & Creative Education'' of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License (international): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ For the avoidance of doubt, by applying this license KKHSOU does not waive any privileges or immunities from claims that it may be entitled to assert, nor does KKHSOU submit to the jurisdiction, courts, legal processes or laws of any jurisdiction. Printed and published by Registrar on behalf of the Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University Headquarters : Patgaon, Rani Gate, Guwahati - 781017 City Office : Housefed Complex, Dispur, Guwahati-781006; Web: www.kkhsou.in 2 Handbook on Art & Creative Education INTRODUCTION This "Handbook on Art & Creative Education" has been designed to empower the teacher trainees with the necesary knowledge and skills on art education. -

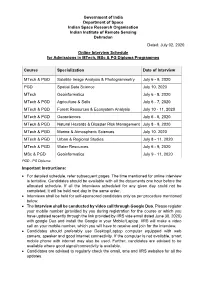

Revised Interview Schedule for Admissions in Mtech, Msc & PG Diploma Courses

Government of India Department of Space Indian Space Research Organisation Indian Institute of Remote Sensing Dehradun Dated: July 02, 2020 Online Interview Schedule for Admissions in MTech, MSc & PG Diploma Programmes Course Specialization Date of Interview MTech & PGD Satellite Image Analysis & Photogrammetry July 6 - 9, 2020 PGD Spatial Data Science July 10, 2020 MTech Geoinformatics July 6 - 8, 2020 MTech & PGD Agriculture & Soils July 6 - 7, 2020 MTech & PGD Forest Resources & Ecosystem Analysis July 10 - 11, 2020 MTech & PGD Geosciences July 6 - 8, 2020 MTech & PGD Natural Hazards & Disaster Risk Management July 8 - 9, 2020 MTech & PGD Marine & Atmospheric Sciences July 10, 2020 MTech & PGD Urban & Regional Studies July 8 - 11, 2020 MTech & PGD Water Resources July 6 - 9, 2020 MSc & PGD Geoinformatics July 9 - 11, 2020 PGD - PG Diploma Important Instructions: For detailed schedule, refer subsequent pages. The time mentioned for online interview is tentative. Candidates should be available with all the documents one hour before the allocated schedule. If all the interviews scheduled for any given day could not be completed, it will be held next day in the same order. Interviews shall be held for self-sponsored candidates only as per procedure mentioned below. The Interview shall be conducted by video call through Google Duo. Please register your mobile number (provided by you during registration for the course or which you have updated recently through the link provided by IIRS vide email dated June 30, 2020) with google Duo and install the Google in your Mobile/Laptop. IIRS will make a video call on your mobile number, which you will have to receive and join for the interview.