Empire State's Cultural Capital at Risk?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC Parks Department List of Capital Projects for FY18 Budget in Community District 11 That Need Funding (See Attached)

COMMUNITY BOARD ELEVEN BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN 1664 PARK AVENUE NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10035 Diane Collier Chair TEL: (212) 831-8929/30 Angel D. Mescain FAX: (212) 369-3571 District Manager www.cb11m.org Environment, Open Space, & Parks Committee Thursday, October 13, 2016, 6:00 p.m. Board Office ***MINUTES*** Informal Public Meeting without Quorum Present: David Giordano, Frances Mastrota, Jacqueline Nelson, Russell Shuler, Marie Winfield Excused: Brodie Enoch, James Garcia Absent: Alvin Johnson*, Peggy Morales, Chandra Smith Guests: Debbie Quinones, Vice Chair, Community Board 11; Jesse Gubert, Randall’s Island Park Alliance (RIPA); Renee Keitt, Chenchita’s Garden; Ann-Gel Palermo, East Harlem Communities Active in Disasters (EHCOAD), East Harlem Emergency Preparedness Collaborative (EHEPC); Carol Johnson, CERT 11, EHCOAD; Chantal Gailloux; Chrstine Johnson, Pleasant Village Community Garden; Aziz Deakan, New York City Community Gardens Coalition (NYCCGC); Jordan Baltimore, New York Empire Baseball; Gilbert Rawlins; Bill LoSasso, Green Thumb; Kenny Williams, Green Thumb; Robin E. Dickens, NYCCGC, Harlem Mandela Garden *Committee member informed committee leadership that he would not be serving on the committee on September 1, 2016. Committee leadership informed by staff that A. Johnson was removed from committee roster on October 14, 2016. 1. Call to Order- Adoption of the Agenda Chair Frances Mastrota called the meeting to order at 6:00pm. The committee did not have quorum and proceeded for informational purposes for the benefit of the public in attendance. 2. Announcements a. Marx Brothers Playground (located on 96th Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues) will be reconstructed during the Educational Construction Fund project for Co-Op Tech High School. -

REVIEW 2013 - 2014 Dear Friend of Randall’S Island Park

REVIEW 2013 - 2014 Dear Friend of Randall’s Island Park, Thank you for your interest in Randall’s Island Park. As Co-Chairs of the Randall’s Island Park Alliance (RIPA) Board of Trustees, we invite you to enjoy our 2013-2014 Review. RIPA’s continued success in reaching our goals comes through the great work and generosity of our many partners and supporters – a true Alliance in support of the Park’s programs, fields, facilities and natural areas. You will find in the following pages photos and acknowledgements of the many local program partners, donors, volunteers, elected officials and City and State agencies who have helped to bring us to this point. We are especially grateful to the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation for extraordinary support and guidance throughout our successful partnership of more than 20 years. Following its recent transformation, Randall’s Island Park’s visibility continues to grow, and more and more New Yorkers are visiting its shores. Our fellow Board Members, challenged and inspired by what the Park can be, continue to contribute countless hours and crucial support. In 2014 the Board undertook a comprehensive plan for improvement and expansion of our free public programs. Visits to the Island have nearly doubled in recent years, to approximately 3 million! We expect our increased free programming will continue to expand our universe of visitors and friends. Many thanks to these millions of fans who visit and who compliment the Park through positive feedback on our social media, sharing photos and observations, and who help us to grow our Alliance every day. -

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A

Four Star Films, Box Office Hits, Indies and Imports, Movies A - Z FOUR STAR FILMS Top rated movies and made-for-TV films airing the week of the week of April 25 - May 1, 2021 Alien (1979) Freeform Mon. 5:10 p.m. Aliens (1986) Freeform Mon. 7:50 p.m. Forrest Gump (1994) VH1 Fri. 9 p.m. VH1 Sat. 5 p.m. The Godfather, Part II (1974) TMC Sun. 2 p.m. Showtime Tues. 2:50 p.m. The Godfather (1972) TMC Sun. 11 a.m. Halloween (1978) AMC Fri. 7 p.m. AMC Sat. 4 p.m. The Little Mermaid (1989) Freeform Tues. 8 p.m. Mary Poppins (1964) Freeform Sun. 7 a.m. Freeform Sun. 5 p.m. Mrs. Miniver (1942) TCM Sun. 3:45 a.m. Platoon (1986) AXS Mon. 6 p.m. AXS Mon. 8:45 p.m. AXS Tues. 6 a.m. EPIX Tues. 6 p.m. Pulp Fiction (1994) IFC Sun. 5:30 p.m. IFC Sun. 9 p.m. AMC Thur. 9 a.m. The Shawshank Redemption (1994) FX Sun. 5 p.m. The Shining (1980) AMC Sat. 8:30 a.m. The Silence of the Lambs (1991) Showtime Sat. 2 p.m. Singin' in the Rain (1952) TCM Sun. 3 p.m. Sounder (1972) TCM Sun. 9 p.m. The Spirit of St. Louis (1957) TCM Mon. 2:30 a.m. Stagecoach (1939) TCM Mon. 11:15 a.m. A Star Is Born (1937) TCM Mon. 3 p.m. A Star Is Born (1954) TCM Mon. 5 p.m. Strangers on a Train (1951) TCM Tues. -

Library Aid 2018-19

State Aid Report 2018-2019 Education Law 273, Chapter 917, Laws of 1990 as amended 3R's CCDA %change %change 2017- 2015-2016 Per Student 2017-2018 2018-2019 2018 Approp College Base Grant Ed Law Ed Law w/HH Approp. Total FTE FTE Grant Approp EdLaw to 2018-2019 Approp Approp ADELPHI UNIVERSITY 8,069 $4,400 $8,392 $11,877 $12,792 $12,792 $12,094 -5.46% 1.83% ADIRONDACK COMMUNITY COLLEGE 2,765 $4,400 $2,876 $6,905 $7,276 $7,276 $6,879 -5.46% -0.38% ALBANY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY AND HEALTH SCIENCES 1,448 $4,400 $1,506 $5,786 $5,906 $5,906 $5,584 -5.46% -3.49% ALBANY LAW SCHOOL 565 $4,400 $588 $5,101 $4,988 $5,449 $5,152 -5.46% 0.99% ALBANY MEDICAL COLLEGE 1,233 $4,400 $1,282 $5,319 $5,682 $5,682 $5,372 -5.46% 0.99% ALFRED UNIVERSITY 1,814 $4,400 $1,886 $5,749 $6,286 $6,286 $5,943 -5.46% 3.38% AMER ACADEMY OF DRAMATIC ARTS 311 $4,400 $323 $4,415 $4,723 $4,723 $4,465 -5.46% 1.14% AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY 45 $4,400 $47 $4,166 $4,447 $4,447 $4,204 -5.46% 0.92% BANK STREET COLLEGE OF EDUCATION 781 $4,400 $812 $5,101 $5,212 $5,449 $5,152 -5.46% 0.99% BARD COLLEGE 3,201 $4,400 $3,329 $7,044 $7,729 $7,729 $7,307 -5.46% 3.74% BARNARD COLLEGE 2,555 $4,400 $2,658 $6,576 $7,058 $7,058 $6,673 -5.46% 1.48% BORICUA COLLEGE 1,067 $4,400 $1,110 $5,345 $5,510 $5,709 $5,398 -5.46% 0.99% BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN COMM COLLEGE 21,048 $4,400 $21,890 $24,720 $26,290 $26,290 $24,856 -5.46% 0.55% BRONX COMMUNITY COLLEGE 8,288 $4,400 $8,619 $12,373 $13,019 $13,019 $12,309 -5.46% -0.52% BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL 1,640 $4,400 $1,706 $6,062 $6,106 $6,475 $6,122 -5.46% 0.99% -

Spring 2012 Connections Magazine (PDF

Nonprofit Org. U.S. Postage PAID 2 Union Ave. Permit No. 19 Saratoga Springs, NY 12866-4390 Saratoga Springs, NY 12866-4391 printed on recycled paper MAGAZINE COLLEGE STATE connections connections EMPIRE THE Artwork by Ivy Stevens-Gupta, above, winner of the 2011 Student Art Contest, who explains in her artist’s statement that her experience with the college inspired her to start Ivy Stevens, Central New York Center painting again after many years away from her easel. 2012 Empire State College STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Field of Flowers • Student Art Award 2011 SPRING It’s time to start making your plans to come to Saratoga Springs for our signature summer events. Our annual day at Saratoga Race Course is Friday, July 27 and our annual evening at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center is Friday, August 17. For our out-of-town visitors, we will secure room blocks at our local hotels. We invite you to come and enjoy this charming and historic community and, of course, to spend time with good friends at SUNY Empire State College. We hope to see you and your families! Saratoga For more information or to sign up online, go to www.esc.edu/AlumniEvents. Summer There’s nothing like it. Make a decision today to create a better tomorrow Create a better tomorrow by including Empire State College in your will today. Your bequest can make college more affordable for a deserving student in need. With your investment, you give the gift of opportunity to our students working to improve their lives and their communities. -

Teamup AUDL Power Rankings

TeamUp Fantasy AUDL Power Rankings (7/8 - 7/14) https://www.teamupfantasy.com/ 1. Chicago Union The Union have earned the number one spot this week. They are now 5-0 after their win against the Radicals. Chicago's offense has so many weapons and they manage to take smart shots. In their game this past weekend, their defense played better than they have before. If they keep up this level of play they will have a good shot at the title. 2. DC Breeze DC is moving up a spot this week. Last weekend they beat the Empire in impressive fashion. They won by three, but New York scored a couple goals in the final minutes of the game. DC’s offense performed extremely well - as they always do - and their defense managed to get a ton of run through Ds. 3. New York Empire New York is stepping down from their pedestal this week. After being at the top for the first five weeks of the season, the Empire lost to the Breeze. The Empire allowed the Breeze to get too many run through Ds that could have been fixed. The Empire are still a great team and are still scary to face. 4. Raleigh Flyers The Flyers managed to beat the Cannons last week. With that being said, they are staying in the number four spot this week. They have another game against the Cannons next week, which should be another easy win. This team has a lot of potential to make it deep into the playoffs this year. -

Coaching Continuous Improvement

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT IN COACHING November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 1 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT • Attending this conference is an active action of Continuous Improvement • Interaction at events like this expands your thinking and generates new ideas • This will lead to improvements in your approach to challenges November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 2 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT • Is an ongoing effort to improve products, services or processes. These efforts can seek “incremental” improvement over time or “breakthrough” improvement all at once • Simple approach to making things better • A process to deal with the things you don’t get right in the original plan November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 3 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT • Engineering Manager at Liburdi Turbine Services (LTS) • LTS – repairs gas turbine components using processes including welding, machining and coating November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 4 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 5 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT • Plan Do Check Act November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 6 CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT • Plan Do Check Act November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - Halifax 7 Real Life Example • 2014 Toronto RUSH • May 9th Game Versus New York Empire • The RUSH won 28-25 • Post game break down • Seared into my mind was the picture of the Empire handlers launching discs at will November 15, 2015 Ultimate Canada Conference 2015 - -

2019-2020 Newsletter -PDF

Sport Management Sport Analytics Syracuse2019-2020 Newsletter Persevering Through 2020’s Challenges How our students, faculty and alumni embraced virtual learning, remote employment View a text-based accessible version CO VER ST OR Y Persevering Through How our students, faculty and alumni embraced virtual learning, remote employment We welcomed a new decade with innovative ideas and graduated our largest class of students in May 2020, but even with the excitement surrounding major milestones, this new chapter did not unfold as we – or anyone - had planned. We persevered through a pandemic and we could not have done it without the unwavering commitment from our Sport Management faculty and staff, the understanding and flexibility of our students, the guidance from Falk College and Syracuse University leadership, and the loyal support of our alumni and advisory council members. So many of our events, trips, conferences, presentations, lectures and internships were canceled or cut short, including senior Capstones, graduate practicums, Los Angeles Immersion, Syracuse Sport Business Conference, Berlin Sport Analytics Faculty adapt from classroom instruction to online teaching Undergraduate director Dr. Gina Pauline dents both online and in person. I also experienced the challenges of being The Spring 2020 semester brought an unexpected challenge that no one a full-time working mother with three kids at home who were also learning saw coming. Think about it, 20 years from now, we will look back on this remotely. It was a juggling act for sure! We all came out stronger in the end year and say, “Remember when you were quarantined at home for months and I’m proud of my family, our students and everyone in the department and everything was shut down due to a global pandemic?” Everyone will who worked together in these difficult times. -

Government, Law and Policy Journal

NYSBA SUMMER 2011 | Vol. 13 | No. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal A Publication of the New York State Bar Association Committee on Attorneys in Public Service, produced in cooperation with the Government Law Center at Albany Law School NNewew YYorkork SState’state’s BBudget:udget: CConflictsonflicts aandnd CChallengeshallenges In Memoriam Governor Hugh L. Carey 1919-2011 The Committee on Attorneys in Public Service dedicates this issue to the enduring memory of Governor Hugh L. Carey and his enumerable contributions to public service This photograph, which is entitled Governor Carey Briefs the Press on the Budget, was made available from the New York State Archives. SUMMER 2011 | VOL. 13 | NO. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal Contents Board of Editors 2 Message from the Chair J. Stephen Casscles Peter S. Loomis Lisa F. Grumet 3 Editor’s Foreword James F. Horan Rose Mary K. Bailly Barbara F. Smith 4 Guest Editor’s Foreword Patricia K. Wood Abraham M. Lackman Staff Liaison 5 Legal History of the New York State Budget Albany Law School David S. Liebschutz and Mitchell J. Pawluk Editorial Board 11 Pataki v. Assembly: The Unanswered Question Rose Mary K. Bailly Hon. James M. McGuire Editor-in-Chief 17 New York State School Finance Patricia E. Salkin Shawn MacKinnon Director, Government Law Center 24 CFE v. State of New York: Past, Present and Future Michael A. Rebell Vincent M. Bonventre Founding Editor-in-Chief 31 Changing the Terms of New York State’s Budget Conversation Richard Ravitch Student Editors 35 New York’s Economy: From Stagnation to Decline Robert Barrows Abraham M. -

Bringing Quality and Equity Together Mapping Guided Pathways for First Generation Student Success

Bringing Quality and Equity Together Mapping Guided Pathways for First Generation Student Success A LEAP Centennial Forum New York, New York November 17, 2015 PARTICIPANT LIST AS OF NOVEMBER 9, 2015 Adelphi University Berkeley College Tuval Foguel Judith Kornberg Perry Greene Della Hudson Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Chotsani West Chrystie Hill Paul Markham Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Elizabeth Boylan Bonner Foundation Robert Hackett Allied American University Diane Sykes Cabrini College Kim Boyd American Council of Learned Societies Saleem Brown Steven Wheatley Nakia Mack George Stroud American Council on Education Shannon Zottola Louis Soares CAMBA Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Christie Hodgkins Eugene Tobin Cedar Crest College Bard College Janet Baker Mark Halsey Rosanna Cabatic Amy Savage Noalani Hendricks Rebecca Thomas Nichelle Hunt Elizabeth Ortiz Barnard College Rebecca Seaman Becky Friedkin Calley Stevens Taylor Nikki Youngblood Giles Robert Wilson Michell Tollinchi-Michel Sarah Wolcott Bergen Community College City University of New York Gail Fernandez Kenneth Norz Jaymee Griffin Ekaterina Sukhanova Yun Kim Mari Watanabe-Rose Ilene Kleinman Jill Rivera City University of New York City University of New York Borough of Manhattan Community College Stella and Charles Guttman Community College Jean Amaral Valora Blackson Kristin Bennett Nicola Blake Allana Burke Stuart Cochran Megan Elias Mary Coleman Jordan Evans Scott Evenbeck Courtney Fusco Karla Fuller Alexandra Pyak Laura Gambino Carei Thomas Jane E Hindman Joan Lucariello City University of New York Linda Merians Bronx Community College Nicole Saint-Louis Vida Samuel Marissa Schlesinger John Stroud City University of New York College of Staten Island Hildegard Hoeller Colgate University Nan Sussman Drea Finley Georgia Frank City University of New York Graduate Center Katina Rogers College of Saint Elizabeth Monique Guillory-Winfield City University of New York Patricia Heindel Herbert H. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 617 HE 033 460 TITLE The Independent Study Catalog. 7th Edition. INSTITUTION National Univ. Continuing Education Association, Washington, DC.; Peterson's Guides, Inc., Princeton, NJ. ISBN ISBN-0-7689-0008-5 ISSN ISSN-0733-6020 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 400p.; For the sixth edition, see ED 405 788. AVAILABLE FROM Peterson's, 202 Carnegie Center, P.O. Box 2123, Princeton, NJ 08543-2123 ($21.95). Tel: 800-338-3282 (Toll Free); Fax: 609-243-9150. Web site: http://www.petersons.com. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) -- Reference Materials - Directories /Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Continuing Education; Correspondence Schools; *Correspondence Study; Elementary Secondary Education; *Extension Education; *External Degree Programs; Graduate Study; High School Equivalency Programs; Higher Education; Home Study; *Independent Study; Lifelong Learning; Noncredit Courses; Nontraditional Education ABSTRACT This directory lists high school, college, and graduate study at-home opportunities, including extensive information about external degree and certificate programs offered by accredited institutions that participate in University Continuing Education Association programs. An introductory section, which explains what independent study is and how it works, is highlighted by profiles of individuals who have traveled this route. Another short section explains how to use the catalog listings. The catalog listings themselves provide short profiles of participating institutions, including cost and whom to contact. Indexes include: (1) geographical;(2) external degree;(3) certificate program;(4) institutions accepting international students;(5) alphabetical guide to subject areas; and (6) subject areas. (CH/EV) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

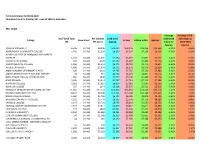

This Chart in .PDF Format

Estimated Library Aid 2019-2020 Education Law 273, Chapter 917, Laws of 1990 as amended 3R's CCDA %change %change 2018- 2017-2018 Total Per Student 2018-2019 2019-2020 2019 Approp College Base Grant Ed Law Ed Law w/HH Approp. FTE FTE Grant Approp EdLaw to 2019-2020 Approp Approp ADELPHI UNIVERSITY 8,506 $4,400 $8,846 $12,094 $13,246 $13,246 $12,530 -5.41% 3.60% ADIRONDACK COMMUNITY COLLEGE 2,783 $4,400 $2,894 $6,879 $7,294 $7,294 $6,900 -5.41% 0.30% ALBANY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY AND HEALTH SCIENCES 1,434 $4,400 $1,491 $5,584 $5,891 $5,891 $5,572 -5.41% -0.20% ALBANY LAW SCHOOL 622 $4,400 $647 $5,152 $5,047 $5,449 $5,154 -5.41% 0.05% ALBANY MEDICAL COLLEGE 1,260 $4,400 $1,310 $5,372 $5,710 $5,710 $5,401 -5.41% 0.54% ALFRED UNIVERSITY 1,806 $4,400 $1,878 $5,943 $6,278 $6,278 $5,938 -5.41% -0.08% AMER ACADEMY OF DRAMATIC ARTS 326 $4,400 $339 $4,465 $4,739 $4,739 $4,483 -5.41% 0.39% AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY 50 $4,400 $51 $4,204 $4,451 $4,451 $4,210 -5.41% 0.14% BANK STREET COLLEGE OF EDUCATION 806 $4,400 $838 $5,152 $5,238 $5,449 $5,154 -5.41% 0.05% BARD COLLEGE 3,185 $4,400 $3,313 $7,307 $7,713 $7,713 $7,296 -5.41% -0.16% BARNARD COLLEGE 2,584 $4,400 $2,687 $6,673 $7,087 $7,087 $6,704 -5.41% 0.46% BORICUA COLLEGE 937 $4,400 $974 $5,398 $5,374 $5,709 $5,400 -5.41% 0.05% BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN COMM COLLEGE 21,302 $4,400 $22,154 $24,856 $26,554 $26,554 $25,118 -5.41% 1.05% BRONX COMMUNITY COLLEGE 8,412 $4,400 $8,748 $12,309 $13,148 $13,148 $12,437 -5.41% 1.04% BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL 1,640 $4,400 $1,706 $6,122 $6,106 $6,475 $6,125 -5.41% 0.05%