The Renewable Energy Sector in Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABOUT PIPELINES OUR ENERGY CONNECTIONS the Facts About Pipelines

ABOUT PIPELINES OUR ENERGY CONNECTIONS THE facts ABOUT PIPELINES This fact book is designed to provide easy access to information about the transmission pipeline industry in Canada. The facts are developed using CEPA member data or sourced from third parties. For more information about pipelines visit aboutpipelines.com. An electronic version of this fact book is available at aboutpipelines.com, and printed copies can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. The Canadian Energy Pipeline Association (CEPA) CEPA’s members represents Canada’s transmission pipeline companies transport around who operate more than 115,000 kilometres of 97 per cent of pipeline in Canada. CEPA’s mission is to enhance Canada’s daily the operating excellence, business environment and natural gas and recognized responsibility of the Canadian energy transmission pipeline industry through leadership and onshore crude credible engagement between member companies, oil production. governments, the public and stakeholders. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Canada’s Pipeline Network .................................1 2. Pipeline Design and Standards .........................6 3. Safety and the Environment ..............................7 4. The Regulatory Landscape ...............................11 5. Fuelling Strong Economic ................................13 and Community Growth 6. The Future of Canada’s Pipelines ................13 Unless otherwise indicated, all photos used in this fact book are courtesy of CEPA member companies. CANADA’S PIPELINE % of the energy used for NETWORK transportation in Canada comes 94 from petroleum products. The Importance of • More than half the homes in Canada are Canada’s Pipelines heated by furnaces that burn natural gas. • Many pharmaceuticals, chemicals, oils, Oil and gas products are an important part lubricants and plastics incorporate of our daily lives. -

Ombudsman Inside Pages

Provincial Ombudsman June, 2001 The Honourable Myron Kowalsky Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Province of Saskatchewan Legislative Building REGINA, Saskatchewan S4S 0B3 Dear Mr. Speaker: It is my duty and privilege to submit to you and to the Members of the Legislature, in accordance with the provisions of section 30 of The Ombudsman and Children’s Advocate Act, the twenty-eighth Annual Report of the Provincial Ombudsman. Respectfully submitted, Barbara J.Tomkins OMBUDSMAN promoting fairness Suite 150 - 2401 Saskatchewan Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 3V7 Tel: 306.787.6211 1.800.667.7180 Fax: 306.787.9090 Email:[email protected] Provincial Ombudsman 2000 Annual Report Provincial Ombudsman Table of Contents Staff at December 31, 2000 Regina Office: Articles Articles Page Gordon Mayer Looking Back 1 General Counsel Service to Northern Residents 3 Murray Knoll Fairness and Lawfulness: Let’s Talk Turkey 7 Deputy Ombudsman I’m Sorry, She’s In a Meeting 10 Roy Hodsman A Moving Tribute 14 Ombudsman Assistant Budget 17 Arlene Harris Ombudsman Assistant Kudos Honour Roll 18 Top Ten List 21 Brian Calder Ombudsman Assistant We’re Here For You 24 Susan Krznar Ombudsman Assistant (Temp.) Special Investigation Susan Griffin Ombudsman Assistant (ACR) Imposition of Ban on Smoking at Carol Spencer Saskatchewan Correctional Facilities 4 Complaints Analyst Cheryl Mogg Communications Co-ordinator Case Summaries Page Debra Zick Executive Secretary Saskatchewan Justice - Sheriff’s Office 2 Andrea Lamont SaskEnergy 6 Secretary Health District 8 (to -

Canwest Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies

Wednesday, September 30, 2009 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan TheStarPhoenix.com D1 New Top 100 list showcases Sask.’s diversification By Katie Boyce almost $3 billion since 2007. Viterra Inc., in its second year of his year’s Top 100 Saskatchewan operation, has also experienced significant Companies list is filled with sur- growth in revenue, jumping by almost T prises. $3 billion in the last year to claim third Besides a new company in the No. 1 spot, ranking. Long-standing leaders Canpotex 23 businesses are featured for the first time Limited and Cameco Corporation continue in the 2009 ranking, which is based on 2008 to make the top five, backed by the profit- gross revenues and sales. The additions able potash market. — headquartered in Carlyle, Davidson, Este- One major modification to this year’s list van, Lampman, Melfort, Regina, Rosetown, has been to exclude the province’s individual Saskatoon, Warman, and Yorkton — show retail co-operatives, instead allowing Feder- off the incredible economic growth that our ated Co-operatives Ltd. to represent these province has experienced during the last year. businesses. Another change has been in how 1 Covering a wide cross-section of industries SaskEnergy reports its revenue. Rather than in our province, newcomers to the list include providing gross revenue amounts, the crown PotashCorp Allan Construction, Kelsey Group of Compa- corporation started this fiscal year to report nies, Partner Technologies Incorporated and only net revenue, which accounts for the Reho Holding Ltd. (owner of several Warman significant drop in rankings. companies) in the manufacturing and con- The Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies is struction field, and Arch Transco Ltd. -

Electricity in Saskatchewan

Electricity In Saskatchewan An Educational Resource for Grade 6 Science Section Electricity comes Lesson 1.1 Activity to Saskatchewan Lesson 1.1 Teacher Answer Key 1.0 Lesson Overview and Outcomes Lesson 1.1 Student Worksheet Page 4 Renewable and Non-renewable Resources Section Lesson Overview and Outcomes Saskatchewan is growing and so is our need As much as possible, teachers are forwarded for power. With a population of 1,142,570 to the SaskPower website as that will have Lesson 2.1 Coal Info Sheet Lesson 2.4 Wind Info Sheet 2.0 Lesson 2.1 Activity Lesson 2.4 Activity as of January 1, 2016, and industry and the most current content. Student handouts Page 8 Lesson 2.1 Teacher Answer Key Lesson 2.4 Teacher Answer Key businesses popping up all the time, keeping will be updated annually, but if there is a Lesson 2.1 Student Worksheet Lesson 2.4 Student Worksheet up with the electrical demand is both discrepancy between the printed copy and challenging and providing some unique the website, please defer to the content on Section Lesson 2.2 Natural Gas Info Sheet Lesson 2.5 Solar, Nuclear, Biomass Lesson 2.2 Activity and Geothermal Activity opportunities. saskpower.com. Lesson 2.2 Teacher Answer Key Lesson 2.5.1 Solar Info Sheet Lesson 2.2 Student Work Sheet Lesson 2.5.2 Nuclear Info Sheet This resource provides ways for students to This resource was developed by SaskPower 3.0 Lesson 2.5.3 Biomass Info Sheet inquire and explore a variety of topics when with input from the following educators Page 33 Lesson 2.3 Hydro Info Sheet Lesson 2.5.4 Geothermal Info Sheet it comes to producing power, delivering who provided valuable ideas, feedback and Lesson 2.3 Activity Lesson 2.5 Teacher Answer Key it, conserving it and the ethical, social and expertise. -

Corporate Procurement Committee

Corporate Procurement Committee The Corporate Procurement Committee (CPC) consists • Encourage Saskatchewan content in procurement of members from major Saskatchewan corporations processes with major contractors. representing: • Crown corporations, • the private sector, and • government ministries. For more information contact: Mr. Scott Summach Mission Statement Deputy Director, Investment The mission of the Corporate Procurement Committee Saskatchewan is to promote Saskatchewan economic growth by Ministry of Trade and Export Development developing quality, competitive suppliers of goods and 219 Robin Crescent services in Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, SK S7N 6M8 Phone: 306-221-6184 CPC Goals and Objectives Email: [email protected] • Maximize Saskatchewan content in the acquisitions of goods and services in accordance with trade agreements. • Increase awareness of Saskatchewan supplier capabilities. • Encourage the export of goods and services by Saskatchewan suppliers. • Identify opportunities to Saskatchewan suppliers. • Share procurement best practices. • Maximize Aboriginal content in the acquisition of goods and services. • Encourage the implementation of Quality Assurance Programs by Saskatchewan suppliers. Action Plan This is accomplished by: • Meeting as a Committee four times a year. • Sharing information on suppliers, new product, success stories, and Saskatchewan and Aboriginal content statistics. • Visiting supplier facilities in conjunction with meetings. • Providing information to the Ministry of Trade and Export Development -

Contact Information

Application to Participate(A93483) Filing Date: 2018-08-10 Hearing Information Project Name: NGTL - 2021 System Expansion Project Company: NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. File Number: OF-Fac-Gas-N081-2018-03 02 Hearing Order: GH-003-2018 I am Applying as: { An Individual { Authorized Representative on Behalf of an Individual ~ A Group Select which one best describes your group: ~ Company { Association (Special Interest Group) { Aboriginal { Federal Government { Provincial Government { Territorial Government { Municipal Government { Others ~ My group is an organization that will represent its own interests { My group is a collection of individuals with common interest Contact Information: 517 Tenth Avenue SW Telephone/Téléphone : (403) 292-4800 Calgary, Alberta T2R 0A8 Facsimile/Télécopieur : (403) 292-5503 http://www..neb-one.gc.ca 517, Dixième Avenue S.-O. 1-800-899-1265 Calgary, (Alberta) T2R 0A8 1 • If you apply as individual, the contact information is for the Person Applying to Participate. • If you apply as Authorized Representative, the contact information is for the Individual you are representing. • If you apply as Group, the contact information is for the Group’s main contact. Salutation: Mr. Last Name: Jordan First Name: Terry Title: Senior Legal Counsel Address: Organization: TransGas Limited 1000 - 1777 Victoria Avenue Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4K5 Telephone: 306-777-9063 Canada Facsimile: 306-565-3332 Email Address: [email protected] Authorized Representative(s) Information: If you do not have an authorized representative -

Many Islands Pipe Lines (Canada) Limited Northwest Supply Expansion 2018 Project Overview Many Islands Pipe Lines (Canada) Limit

Many Islands Pipe Lines (Canada) Limited Northwest Supply Expansion 2018 Project Overview Many Islands Pipe Lines (Canada) Limited (MIPL(C)L) is a federally regulated and wholly owned subsidiary of SaskEnergy Incorporated, a Saskatchewan Crown Corporation. MIPL(C)L is proposing to build a 29-kilometer pipeline from the Nova Gas Transmission Limited (Nova) meter station east of Cherry Grove, AB to the TransGas Limited (TransGas) meter station east of Beacon Hill, SK. Additionally, a new compressor station is proposed to be constructed near the west end of this pipeline, within Saskatchewan. Residential, commercial, and industrial customer growth has increased demand for natural gas in Saskatchewan. Construction of the proposed project will support this growth by allowing for additional natural gas supply to be transported into Saskatchewan from Alberta through the Nova system to existing TransGas facilities in the area. Keeping our stakeholders informed is an important aspect of all our major projects. Stakeholder engagement is achieved through landowner, public, Aboriginal, and community involvement. We continually invest in Saskatchewan and believe strongly in working together with these partners when projects are being planned and developed. MIPL(C)L will submit an application to the National Energy Board (NEB) to seek the necessary approval for the proposed project. If you are unable to provide comments regarding the proposed project to MIPL(C)L, or prefer to do so directly to the NEB, you may do so by contacting: National Energy Board Suite 210, 517 Tenth Ave SW Calgary AB T2R 0A8 www.neb-one.gc.ca Toll free: 1-800-899-1265 Toll free fax: 1-877-288-8803 Frequently Asked Questions Why is this expansion needed? Residential, commercial, and industrial customer growth has increased demand for natural gas in Saskatchewan. -

UAV Image Acquisition Services

ENVIRONMENT UAV Image Acquisition Services Recent developments in Unoccupied Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technologies have spawned opportunities for small-scale image capture (for facilities, mining, forestry, agriculture, etc.). Conventional fixed-wing aircraft and satellites are too costly to be used to capture imagery for small geographic areas —using UAVs we can now meet this need. The Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) has many years of experience in remotely-sensed data acquisition and now offers UAV services to support industry and government as a cost-effective alternative to conventional methods. These small, environmentally-friendly vehicles (under 3 kg) are autonomous aircraft that fly a pre-programmed flight path to capture high-resolution imagery for small geographic areas (less than 1,000 ha). Services offered: • High-resolution image acquisition o Ground resolutions from 1.6 – 3 cm o Typical flight elevations from 60 – 110 m above ground (with terrain- following capability) o Shade-free image capability (when UAV flies under cloud cover) o Typical flights cover 30-50 ha; multi-flight capability • GPS ground control to improve positional accuracies • Image processing services o GIS-ready digital ortho-photos with metadata o Digital terrain data o Volumetric calculations (gravel pits, chip piles, etc.) o Image editing and analysis o Stereo photo interpretation CONTACT About SRC Jeff Lettvenuk SRC has provided Smart Science Solutions™ for more than 60 years. We are Environmental Performance and Canada’s leading provider of applied research, development, demonstration and Forestry technology commercialization. Our clients benefit from our multidisciplinary T: 306-933-5400 teams that work together to provide solutions to unique challenges in a variety E: [email protected] of industries. -

If You Love Saskatchewan…

If you love Saskatchewan…. Help stop the quiet selling off of our public services The Brad Wall government is quietly starting to privatize our public services. Here are some examples: HEALTH CARE Private, for-profit clinics will now be permitted to offer surgeries in Regina and Saskatoon. The government's move to re-direct $5.5 million in public funds to finance private surgeries and diagnostic tests will mean: . higher costs; . less money for public health services; and . fewer health professionals in the public system. Higher costs The costs of surgeries in private, for-profit clinics will escalate after the initial 'introductory offer', according to the Saskatchewan Health Coalition. For example, the Alberta Health Services says the cost of hip and knee surgery in Edmonton's Royal Alexander Hospital is $4,500, while the cost in the for-profit Health Resources Centre is $14,000. Less money for public health services Diverting government funds to private clinics means less for publicly delivered services. The government has recently put a hold on $3 million in capital funding for a new public outpatient surgical care centre in Regina. Money for more staff and resources that would boost the public health system is now being siphoned off into the pockets of private companies. Staff shortages worsen There is a province-wide shortage of health professionals. Spreading our limited human resources across two systems - public and private - does not solve the problem. In fact, it will make the staff shortages in the public health system worse. We need to maximize staff recruitment and retention in our public hospitals. -

Power Generation Partner Program

POWER GENERATION PARTNER PROGRAM GUIDELINES The information in this document is subject to change without notice. May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Program Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 2. Eligibility Requirements ........................................................................................................................ 3 3. Energy Price .......................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Application Process ............................................................................................................................... 7 5. Interconnection Process ....................................................................................................................... 9 6. Contract Details .................................................................................................................................. 11 7. Summary of Costs ............................................................................................................................... 11 8. Further Information ............................................................................................................................ 12 9. Contact Us ........................................................................................................................................... 14 10. Reference Documents ........................................................................................................................ -

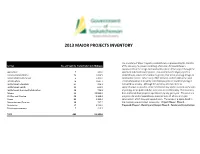

2013 Major Projects Inventory

2013 MAJOR PROJECTS INVENTORY The Inventory of Major Projects in Saskatchewan is produced by the Ministry Sector No. of Projects Total Value in $ Millions of the Economy to provide marketing information for Saskatchewan companies from the design and construction phase of the project through the Agriculture 7 342.0 operation and maintenance phases. This inventory lists major projects in Commercial and Retail 78 2,209.5 Saskatchewan, valued at $2 million or greater, that are in planning, design, or Industrial/Manufacturing 6 3,203.0 construction phases. While every effort has been made to obtain the most Infrastructure 76 2,587.7 recent information, it should be noted that projects are constantly being re- Institutional: Education 64 996.3 evaluated by industry. Although the inventory attempts to be as Institutional: Health 23 610.9 comprehensive as possible, some information may not be available at the time Institutional: Non-Health/Education 48 736.5 of printing, or not published due to reasons of confidentiality. This inventory Mining 15 32,583.0 does not break down projects expenditures by any given year. The value of a Oil/Gas and Pipeline 20 5,168.6 project is the total of expenditures expected over all phases of project Power 85 2,191.6 construction, which may span several years. The values of projects listed in Recreation and Tourism 19 757.7 the inventory are estimated values only. Project Phases: Phase 1 - Residential 37 1,742.5 Proposed; Phase 2 - Planning and Design; Phase 3 - Tender and Construction Telecommunications 7 215.7 Total 485 53,345.0 Value in $ Start End Company Project Location Millions Year Year Phase Remarks AGRICULTURE Namaka Farms Inc. -

Saskpower's 2015-2016 Annual Report

A powerful CONNECTION SASKPOWER 2015-16 ANNUAL REPORT SaskPower has changed its fiscal year-end to March 31 to coincide with that of the Province of Saskatchewan. The first complete fiscal period subsequent to the change is presented in this annual report and consists of the fifteen months ended March 31, 2016. It includes: • Quarter 1 (Q1) through quarter 4 (Q4) = January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2015 • Quarter 5 (Q5) = January 1, 2016, through March 31, 2016 Subsequent fiscal years will consist of the twelve months from April 1 through March 31. EXPANDING OUR LINK TO SASKATCHEWAN’S NORTH In 2015-16, SaskPower completed construction of the 300-kilometre Island Falls to Key Lake (I1K) Transmission Line. Built across the rugged Canadian Shield, the 230-kilovolt line will help meet growing demand for electricity in the North while also improving reliability. Maintaining a positive connection with customers is no small one circuit kilometre of power lines for every three customer feat. The I1K Transmission Line is part of one of the largest accounts. That often means responding to outages in remote power grids in Canada, comprised of nearly 157,000 circuit areas and in all types of weather. kilometres. SaskPower needs it to reach customers throughout We’re making ongoing investments in our expansive grid one one of the most far-reaching service areas in our country — of our top priorities as part of an average $1-billion per year approximately 652,000 square kilometres. infrastructure growth and renewal program that also includes With one of the lowest customer densities relative to grid our generation system.