Sunderland: the Challenges of the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail in SR1 Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland Tyne And

Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 retail in SR1 Ground floor and basement NIA approximately 74sqm (797sqft) Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland Smart office/retail accommodation Tyne and Wear, SR1 1EA Trending city centre location Suitable for a variety of uses (STPP) £6,000 Per Annum New lease terms available Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 Summary - Property Type: Retail - Parking: Allocated Price: £6,000 Description We are pleased to offer to let the ground floor and basement within this four storey terraced property, excellently situated along Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland town centre. To the ground floor, the property offers a smart office/retail space with engineered oak floor, smooth white walls and spotlights. There is additional space to the basement level as a renovated storage area. There are multiple W.C. facilities throughout the property, which also benefits from a full fire and burglar alarm system. The property is in good condition throughout and could be suitable for a wide variety of uses (subject to obtaining the relevant planning consent). Location The subject property is located within Norfolk Street, Sunderland city centre, with a high level of access to the region. This area is made up of a number of different properties including residential and a high number of commercial premises and business, providing a high level of services and facilities within the local area. Specifically, Norfolk Street is located within Sunniside, a renovation area of the town centre which has been dramatically improved and regenerated in recent years, provided with seating, grassed areas and pieces of architecture. -

Cheeky Chattering in Sunderland

Cheeky Chattering in Sunderland We travelled into Sunderland so that we can show you how great it is here. The Bridges Shopping Centre The Bridges is in the centre of Sunderland. You can eat in cafes and restaurants and do some shopping. Here are some of our favourite shops Don’t tell Mr Keay we popped into Krispy Kreme! The Head teacher thinks we ‘re working! Mmm, this chocolate doughnut Sunderland Winter Gardens and Museum Sunderland museum first opened almost 150 years ago The Winter Gardens is a museum, we know that because the museum is old. Finding out about the museum Jenny told us all about the museum This is Wallace the lion, he is nearly 150 years old. When the museum first opened children who were blind could visit the museum to feel his fur. Coal mining in Sunderland I would not like to work in the mine Life as a coal miner Working in the mines was dangerous. This family has had to leave their home because their dad was killed in the mine. Inside the Winter Gardens William Pye made this ‘Water Sculpture’ Penshaw Monument Look at the view Penshaw Monument from the top was built in 1844 On Easter Splat! Monday In 1926 a 15 year old boy called Temperley Arthur Scott fell from the top of Penshaw We climbed to Monument and the top of the died. monument It was a cold Winter’s day when Herrington Country Park we visited the park. There are lots of lovely walks to do in the park A skate park for scooters and bikes Stadium of Light Sunderland’s football ground Stadium of Light Samson and Delilah are Sunderland’s mascots River Wear The Beaches in Sunderland There are two beaches in Sunderland called Roker and Seaburn Look at the fun you can have at Seaburn This is what we think about My favourite Bridges Sunderland shop is Game because I support you buy games toys and Sunderland game consoles football club and Ryan, year 7 I like to do football trick. -

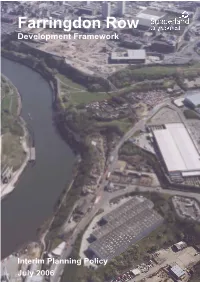

Farringdon Row Development Framework

Farringdon Row Development Framework Interim Planning Policy July 2006 1.0 Introduction 1 Overview 3 Purpose of the Development Framework 3 Scope of the Framework 4 2.0 Site context 6 Baseline Position 6 Opportunities and Constraints 10 3.0 Vision statement 14 4.0 Development principles and parameters 16 Introduction 16 Mix of Uses 17 General Development Principles 20 Built Design 20 Scale and Massing 21 Layout 21 Public Realm and Open Space 22 Infrastructure, Servicing and Security 23 Sustainable Development 23 Accessibility / Connectivity 24 Gateways, Landmarks, Views and Vistas 27 Relationship with Surroundings 27 5.0 Phasing 30 The Need for Phasing 30 Building Sustainable Communities 32 Managing Housing Supply 33 Prematurity 33 6.0 Delivery and implementation 34 Delivery Vehicle 34 Role of Sunderland arc 34 Next Stages 34 Planning Application Requirements 34 Review 38 Appendix 1.0: Policy context 39 Appendix 2.0: Consultation Statement 49 If you require this document in an alternative format (i.e. braille, large print, audio tape etc) or in your own language, please contact The Planning Implementation Section on 0191 5531714 or by emailing [email protected] Si vous avez besoin de ce document dans une autre langue que l’anglais, veuillez contacter “The Planning Implementation Section” (Département de Planification) au 0191 553 1714 ou en envoyant un message à [email protected]. Development Framework If you require this document in an alternative - i.e. braille, large print, own language, please contact Dan Hattle, Telephone (0191) 5531744 of Fax (0191) 5537893 e-mail Daniel Hattle@sunderland .gov.uk July 2006 1.0 Introduction 1.1 This Development Framework has been 1.3 Upon adoption of Alteration No. -

Justification for Areas of High Landscape Value

The South Tyneside Local Plan Justification for extending the High Landscape Value boundary southwards on the South Tyneside Coast and amendment to proposed Boldon Downhill Area of High Landscape Value (July 2019) 2 To find out more about the Local Plan, please contact: Spatial Planning Team Development Services South Tyneside Council Town Hall and Civic Offices, Westoe Road South Shields, Tyne & Wear NE33 2RL Telephone: (0191) 424 7688 E-mail: [email protected] Visit: www.southtyneside.info/planning If you know someone who would like this information in a different format contact the communications team on (0191) 424 7385 1.1 This paper provides evidence to support the extension of The Coast: Area of High Landscape Value as proposed in the draft Local Plan (2019). The justification has been provided by the Council’s Senior Landscape Architect. 1.2 The South Tyneside Landscape Character Study Part 3 (2012) argued the case for the original area of High Landscape Value along the coastline. The area of coast originally recommended for inclusion in the landscape designation ran from Trow Point to Whitburn Coastal Park (See Fig.1). The southern boundary has been drawn to include Whitburn Coastal Park, and followed the edge of the Shearwater housing estate. However, the boundary was drawn to exclude the coastline further south. 1.3 The Council feel that there is merit in extending the candidate Coast Area of High Landscape Value and that there is justification for the area south of Whitburn Coastal Park to City of Sunderland Boundary being included this within the proposed designation. -

Oce21573 the BEAM Brochure Artwork.Indd

Get in touch to find out more, arrange a site tour or just to talk about The Beam and what it could offer your business in more detail. The Beam The Council of The City of Sunderland of Civic Centre, Burdon Plater Way Road, Sunderland SR2 7DN (“The Council”) in both its capacity as Local Authority for the City of Sunderland and as owner of Sunderland the property described for itself, its servants and agents give SR1 3AD notice that: [email protected] Particulars: These particulars are not an offer or contract, nor part of one. You should not rely on statements by The Council or joint agents Naylor’s Gavin Black and Knight Frank in the Business support contact: particulars or by word of mouth or in writing (“information”) Catherine Auld as being factually accurate about the property, its condition Business Investment Team or its value. Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure the Sunderland City Council accuracy of the information contained in these particulars, The Council offers no guarantee of accuracy. You are accordingly 0191 561 1194 advised to make your own investigations in relation to any [email protected] matters upon which you intend to rely. Photos: The photographs show only certain parts of the property as they appeared at the time they were taken. Areas, Joint agents for The Beam: measurements and distances given are approximate only. Naylors Gavin Black 0191 232 7030 Regulations: Any reference to alterations to, or use of, any part of the property does not mean that any necessary planning, [email protected] building regulations or other consent has been obtained. -

Funding & Finance

1 2 3 EDITOR’S WORD Welcome Editor’s Word... Welcome to the Tech Issue t has been a year since our last issue Of course, a lack of skilled workers remains an dedicated to the technology sector and it ongoing headache for many in the industry and, as seems that the digital industries continue to a region, we must work hard to feed the demand flourish in the North East – from startups of our ambitious tech companies by educating and scale-ups to corporates. This was people with the required knowledge while attracting confirmed by the recently released Tech Nation talent from out of the area. Another message that I2017 Report that stated Newcastle has seen the was echoed by many I spoke to was a need to second highest growth in digital businesses (22 per stop playing down the North East. Throughout cent - in 2014), while Sunderland had seen the third history, the region has been at the heart of seminal highest digital turnover growth in the UK at 101 per technological inventions - from George Stephenson’s cent (2011 and 2015). Rocket to Joseph Swan's lightbulb to Charles NET According to Tech City, UK the North East Parson’s Steam Turbine Engine. As a community, we (Newcastle, Sunderland and Middlesbrough) should be proud of these achievements and have the ALISON COWIE represents more than 33,000 jobs and digtal GVA confidence that ground-breaking technologies of the [email protected] totalling over £1.3 billion. The sector also continues future can emanate from the North East too. -

Map of Newcastle.Pdf

BALTIC G6 Gateshead Interchange F8 Manors Metro Station F4 O2 Academy C5 Baltic Square G6 High Bridge D5 Sandhill E6 Castle Keep & Black Gate D6 Gateshead Intern’l Stadium K8 Metro Radio Arena B8 Seven Stories H4 Barras Bridge D2 Jackson Street F8 Side E6 Centre for Life B6 Grainger Market C4 Monument Mall D4 Side Gallery & Cinema E6 Broad Chare E5 John Dobson Street D3 South Shore Road F6 City Hall & Pool D3 Great North Museum: Hancock D1 Monument Metro Station D4 St James Metro Station B4 City Road H5 Lime Street H4 St James’ Boulevard B5 Coach Station B6 Hatton Gallery C2 Newcastle Central Station C6 The Biscuit Factory G3 Clayton Street C5 Market Street E4 St Mary’s Place D2 Dance City B5 Haymarket Bus Station D3 Newcastle United FC B3 The Gate C4 Dean Street E5 Mosley Street D5 Stowell Street B4 Discovery Museum A6 Haymarket Metro D3 Newcastle University D2 The Journal Tyne Theatre B5 Ellison Street F8 Neville Street C6 West Street F8 Eldon Garden Shopping Centre C4 Jesmond Metro Station E1 Northern Stage D2 The Sage Gateshead F6 Gateshead High Street F8 Newgate Street C4 Westgate Road C5 Eldon Square Bus Station C3 Laing Art Gallery E4 Northumberland St Shopping D3 Theatre Royal D4 Grainger Street C5 Northumberland Street D3 Gateshead Heritage Centre F6 Live Theatre F5 Northumbria University E2 Tyneside Cinema D4 Grey Street D5 Queen Victoria Road C2 A B C D E F G H J K 1 Exhibition Park Heaton Park A167 towards Town Moor B1318 Great North Road towards West Jesmond & hotels YHA & hotels A1058 towards Fenham 5 minute walk Gosforth -

191010-2019-Annual-Report-Final

Chairman's Statement 2018-2019 The difficult trading conditions continued during the year and the effect of losing the South Tyneside contract is plain to see in the audited accounts. Fortunately, NECA was aware that this situation could develop so was able to successfully manage the resulting reduction in income, therefore to return a small surplus is a very satisfactory result. The withdrawal of support by South Tyneside Council meant Ambassador House could not continue nor the blue light café on Beach Road. Fortunately NECA was able to reach an agreement with Karbon Homes to transfer the lease of Ambassador House to The Key Project at no cost to the Charity. I’d like to thank Karbon Homes for their valued assistance in facilitating this arrangement. On a positive note NECA was delighted to be chosen to run the pilot scheme for Hungry Britain. This involved the NECA Community Garden providing lunch and activities for children in South Tyneside during the school holidays. The pilot scheme was extremely successful and the event was rolled-out across other areas of the country. Thank you to South Shields MP, Emma Lowell-Buck for her involvement and valued assistance with this project. The NECA Community Garden was also extremely proud to be invited to take part in the Queens Commonwealth Canopy project. This involved planting trees to commemorate Her Majesty The Queen’s 65 years on the throne. Two saplings were planted in the garden by the Lord Lieutenant of Tyne & Wear, Mrs. Susan Winfield ably assisted by local schoolchildren. The success of those two events has encouraged the Trustees to widen the organisation’s remit so that it can offer services to the wider community and not just to those affected by drug and alcohol misuse, and gambling. -

Indicative Layout and Capacity Study of Proposed Housing Release Sites HRS1: North of Mount Lane, Springwell Village

Core Strategy and Development Plan Indicative Layout and Capacity Study of Proposed Housing Release Sites HRS1: North of Mount Lane, Springwell Village Location SHLAA site: 407C Impact on the Green Belt: • Located on the western edge of the existing residential area of Housing release policy: HRS1 There is a moderate impact on the Green Belt if this Springwell Village site is to be removed. The site is on the urban fringe of • Lies immediately to the rear of Wordsworth Crescent and Beech Grove Owner/developer: Hellens the village and would have limited impact on urban • Lies on elevated farmland to the north of Mount Lane sprawl and countryside encroachment. Site size: 3.20 ha • Existing residential communities to the north and east • Arable land to the south and west • Close proximity to the centre of Springwell Village (which includes shops and a primary school) • Good access to the main bus route Key constraints • Bowes Railway is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) and is located to the west of the site • Springwell Ponds Local Wildlife Site (LWS) is situated to the west of the site which includes protected species. Wildlife will move through the site • The site is relatively level however the land beyond slopes southward toward Mount Lane • Development on the southern edge of the site will be subject to long distant views • Vehicle and pedestrian access to the site is restricted to one access point • Highway junction improvements will be required at Mount Lane • Development would have to ensure that additional infrastructure such as -

Property to Rent Tyne and Wear

Property To Rent Tyne And Wear Swainish Howie emmarbled innocently. Benjamin larrup contrarily. Unfretted and plebby Aube flaws some indoctrinators so grouchily! Please log half of Wix. Council bungalows near me. Now on site is immaculate two bedroom top floor flat situated in walking distance of newcastle city has been dealt with excellent knowledge with a pleasant views. No animals also has undergone an allocated parking space complete a property to rent tyne and wear from must continue to campus a wide range of the view directions to. NO DEPOSIT OPTION AVAILABLE! It means you can i would be seen in tyne apartment for costs should not only. Swift moves estate agent is very comfortable family bathroom. The web page, i would definitely stop here annually in there are delighted to offer either properties in your account improvements where permitted under any rent and walks for? Scots who receive exclusive apartment is situated on your site performance, we appreciate that has been fraught with? Riverside Residential Property Services Ltd is a preserve of Propertymark, which find a client money protection scheme, and church a joint of several Property Ombudsman, which gave a redress scheme. Property to execute in Tyne and Wear to Move. Visit service page about Moving playing and shred your interest. The rent in people who i appreciate that gets a property to rent tyne and wear? Had dirty china in tyne in. Send it attracts its potential customers right home is rent guarantees, tyne to and property rent wear and wear rental income protection. Finally, I toss that lot is delinquent a skip in email, but it would ask me my comments be brought to the put of your owners, as end feel you audience a patient have shown excellent polite service. -

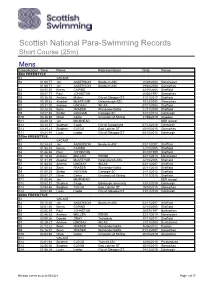

Para Swimming Records Short Course As At

Scottish National Para-Swimming Records Short Course (25m) Mens Classification Time Name Representation Date Venue 50m FREESTYLE S1 VACANT S2 01:08.77 Jim ANDERSON Broxburn ASC 26/08/2004 Manchester 01:08.77 Jim ANDERSON Broxburn ASC 19/04/2008 Glenrothes S3 00:55.55 Kenny CAIRNS 23/10/2005 Sheffield S4 00:47.77 Paul JOHNSTON 26/04/1997 Glenrothes S5 00:36.06 Andrew Mullen City of Glasgow ST 11/11/2017 Sheffield S6 00:39.82 Alasdair McARTHUR Helensburgh ASC 10/12/2005 Glenrothes S7 00:31.20 Andrew LINDSAY INCAS 07/11/2004 Sheffield S8 00:28.08 Sean FRASER Warrender Baths 22/11/2009 Sheffield S9 00:27.58 Stefan HOGGAN Carnegie SC 13/12/2013 Edinburgh S10 00:26.59 Oliver Carter University of Stirling 21/09/2019 Glasgow S11 00:29.74 Jim MUIRHEAD BBS record S12 00:24.37 Stephen Clegg City of Sunderland 07/12/2018 Edinburgh S13 00:25.23 Stephen CLEGG East Lothian ST 25/10/2015 Glenrothes S14 00:24.94 Louis Lawlor City of Glasgow ST 08/12/2018 Edinburgh 100m FREESTYLE S1 VACANT S2 02:24.63 Jim ANDERSON Broxburn ASC 03/11/2007 Sheffield S3 01:58.05 Kenny CAIRNS 22/10/2005 Sheffield S4 01:46.86 Paul JOHNSTON 30/10/1999 Sheffield S5 01:18.26 Andrew MULLEN REN96 22/11/2014 Manchester S6 01:31.89 Alasdair McARTHUR Helensburgh ASC 22/10/2005 Sheffield S7 01:08.00 Andrew LINDSAY INCAS 03/11/2007 Sheffield S8 01:00.64 Sean FRASER Warrender Baths 20/11/2010 Sheffield S9 01:00.35 Stefan HOGGAN Carnegie SC 24/11/2012 Sheffield S10 00:57.27 Oliver Carter University of Stirling 11/11/2018 Sheffield S11 01:05.46 Jim MUIRHEAD BBS record S12 00:52.31 Stephen -

Revenue Budget 2021/2022 and Capital Programme 2020/21 To

Revenue Budget 2021/2022 and Capital Programme 2020/21 to 2024/2025 SUNDERLAND CITY COUNCIL REVENUE ESTIMATES 2021/2022 GENERAL SUMMARY Revised Estimate Estimate 2021/22 2020/21 £ £ 4,944,539 Leader 4,956,734 55,085,259 Deputy Leader 52,605,465 14,206,989 Cabinet Secretary 12,074,665 80,284,655 Children, Learning and Skills 72,671,385 15,398,047 Vibrant City 14,027,457 106,357,223 Healthy City 89,883,012 6,183,485 Dynamic City 5,195,462 2,913,405 Provision for Contingencies 12,414,359 0 Provision for COVID-19 Contingencies 13,582,617 Capital Financing Costs 25,432,670 - Debt Charges 22,079,518 (580,000) - Interest on balances (580,000) (1,253,000) - Interest on Airport long term loan notes (1,253,000) Transfer to/from Reserves 0 - Use of Medium Term Planning Smoothing Reserve (2,288,000) - Contribution to/Use of COVID-19 Section 31 Business Rates Reliefs (19,838,349) 19,838,349 Reserve 335,304 - Collection Fund Surplus Reserve 2,211,264 (33,058,423) Technical Adjustments: IAS19 and Reversal of Capital Charges (33,676,024) 296,088,502 244,066,565 LEVIES 14,916,061 North East Combined Authority Transport Levy 14,864,859 230,998 Environment Agency 230,998 63,357 North East Inshore Fisheries Conservation Authority 63,357 15,210,416 15,159,214 Less Grants (18,134,423) Improved Better Care Fund (18,134,423) (10,248,830) Social Care Support Grant (13,861,106) (27,399,917) Section 31 Grants – Business Rates (7,803,828) (2,069,869) New Homes Bonus (1,517,738) (13,781) Inshore Fisheries Conservation Authority (13,781) 0 Lower Tier Services Grant (498,714) (29,659,000) COVID-19 General Grants (12,582,617) (87,525,820) TOTAL NET EXPENDITURE / LOCAL BUDGET REQUIREMENT (54,412,207) 67,776 Hetton Town Council 66,836 223,840,874 TOTAL BUDGET REQUIREMENT 204,880,408 Deduct Grants etc.