Sunderland Retail Needs Assessment 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail in SR1 Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland Tyne And

Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 retail in SR1 Ground floor and basement NIA approximately 74sqm (797sqft) Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland Smart office/retail accommodation Tyne and Wear, SR1 1EA Trending city centre location Suitable for a variety of uses (STPP) £6,000 Per Annum New lease terms available Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 Summary - Property Type: Retail - Parking: Allocated Price: £6,000 Description We are pleased to offer to let the ground floor and basement within this four storey terraced property, excellently situated along Norfolk Street, Sunniside, Sunderland town centre. To the ground floor, the property offers a smart office/retail space with engineered oak floor, smooth white walls and spotlights. There is additional space to the basement level as a renovated storage area. There are multiple W.C. facilities throughout the property, which also benefits from a full fire and burglar alarm system. The property is in good condition throughout and could be suitable for a wide variety of uses (subject to obtaining the relevant planning consent). Location The subject property is located within Norfolk Street, Sunderland city centre, with a high level of access to the region. This area is made up of a number of different properties including residential and a high number of commercial premises and business, providing a high level of services and facilities within the local area. Specifically, Norfolk Street is located within Sunniside, a renovation area of the town centre which has been dramatically improved and regenerated in recent years, provided with seating, grassed areas and pieces of architecture. -

Oce21573 the BEAM Brochure Artwork.Indd

Get in touch to find out more, arrange a site tour or just to talk about The Beam and what it could offer your business in more detail. The Beam The Council of The City of Sunderland of Civic Centre, Burdon Plater Way Road, Sunderland SR2 7DN (“The Council”) in both its capacity as Local Authority for the City of Sunderland and as owner of Sunderland the property described for itself, its servants and agents give SR1 3AD notice that: [email protected] Particulars: These particulars are not an offer or contract, nor part of one. You should not rely on statements by The Council or joint agents Naylor’s Gavin Black and Knight Frank in the Business support contact: particulars or by word of mouth or in writing (“information”) Catherine Auld as being factually accurate about the property, its condition Business Investment Team or its value. Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure the Sunderland City Council accuracy of the information contained in these particulars, The Council offers no guarantee of accuracy. You are accordingly 0191 561 1194 advised to make your own investigations in relation to any [email protected] matters upon which you intend to rely. Photos: The photographs show only certain parts of the property as they appeared at the time they were taken. Areas, Joint agents for The Beam: measurements and distances given are approximate only. Naylors Gavin Black 0191 232 7030 Regulations: Any reference to alterations to, or use of, any part of the property does not mean that any necessary planning, [email protected] building regulations or other consent has been obtained. -

Map of Newcastle.Pdf

BALTIC G6 Gateshead Interchange F8 Manors Metro Station F4 O2 Academy C5 Baltic Square G6 High Bridge D5 Sandhill E6 Castle Keep & Black Gate D6 Gateshead Intern’l Stadium K8 Metro Radio Arena B8 Seven Stories H4 Barras Bridge D2 Jackson Street F8 Side E6 Centre for Life B6 Grainger Market C4 Monument Mall D4 Side Gallery & Cinema E6 Broad Chare E5 John Dobson Street D3 South Shore Road F6 City Hall & Pool D3 Great North Museum: Hancock D1 Monument Metro Station D4 St James Metro Station B4 City Road H5 Lime Street H4 St James’ Boulevard B5 Coach Station B6 Hatton Gallery C2 Newcastle Central Station C6 The Biscuit Factory G3 Clayton Street C5 Market Street E4 St Mary’s Place D2 Dance City B5 Haymarket Bus Station D3 Newcastle United FC B3 The Gate C4 Dean Street E5 Mosley Street D5 Stowell Street B4 Discovery Museum A6 Haymarket Metro D3 Newcastle University D2 The Journal Tyne Theatre B5 Ellison Street F8 Neville Street C6 West Street F8 Eldon Garden Shopping Centre C4 Jesmond Metro Station E1 Northern Stage D2 The Sage Gateshead F6 Gateshead High Street F8 Newgate Street C4 Westgate Road C5 Eldon Square Bus Station C3 Laing Art Gallery E4 Northumberland St Shopping D3 Theatre Royal D4 Grainger Street C5 Northumberland Street D3 Gateshead Heritage Centre F6 Live Theatre F5 Northumbria University E2 Tyneside Cinema D4 Grey Street D5 Queen Victoria Road C2 A B C D E F G H J K 1 Exhibition Park Heaton Park A167 towards Town Moor B1318 Great North Road towards West Jesmond & hotels YHA & hotels A1058 towards Fenham 5 minute walk Gosforth -

Property to Rent Tyne and Wear

Property To Rent Tyne And Wear Swainish Howie emmarbled innocently. Benjamin larrup contrarily. Unfretted and plebby Aube flaws some indoctrinators so grouchily! Please log half of Wix. Council bungalows near me. Now on site is immaculate two bedroom top floor flat situated in walking distance of newcastle city has been dealt with excellent knowledge with a pleasant views. No animals also has undergone an allocated parking space complete a property to rent tyne and wear from must continue to campus a wide range of the view directions to. NO DEPOSIT OPTION AVAILABLE! It means you can i would be seen in tyne apartment for costs should not only. Swift moves estate agent is very comfortable family bathroom. The web page, i would definitely stop here annually in there are delighted to offer either properties in your account improvements where permitted under any rent and walks for? Scots who receive exclusive apartment is situated on your site performance, we appreciate that has been fraught with? Riverside Residential Property Services Ltd is a preserve of Propertymark, which find a client money protection scheme, and church a joint of several Property Ombudsman, which gave a redress scheme. Property to execute in Tyne and Wear to Move. Visit service page about Moving playing and shred your interest. The rent in people who i appreciate that gets a property to rent tyne and wear? Had dirty china in tyne in. Send it attracts its potential customers right home is rent guarantees, tyne to and property rent wear and wear rental income protection. Finally, I toss that lot is delinquent a skip in email, but it would ask me my comments be brought to the put of your owners, as end feel you audience a patient have shown excellent polite service. -

Real Ale Pubs in Sunderland City Centre, Deptford, Roker & Seaburn

Real Ale Pubs in Sunderland City Centre, Deptford, Roker & Seaburn 1 Version 6.1.1 January 2018 City Centre & Deptford Real Ale Pubs 15 7 9 18 12 16 4 5 13 18 10 19 6 20 14 3 1 11 2 8 This guide shows real ale pubs,in or close to the town centre and are listed in alphabetical order over the next two pages. Please note that information contained may change. Telephone numbers have been provided if you wish to check details. More details about each one can be found on Whatpub.com. Public transport information, correct as of Jab 2018 is only given for those pubs not close to Park Lane Interchange or City Centre bus stops If you have any updates please email [email protected]. 2 City Centre & Deptford Real Ale Pubs 1 CHAPLINS 7 HANOVER 40 Stockton PLACE Road, Deptford Sunderland Sunderland SR1 3NR SR4 6BY 0191 5673562 0191 5658888 Buses 8, 10, 11 20,73, 135/136 2 CHESTERS 8 IVY HOUSE Chester Road, Worcester Tce Sunderland Ashbrooke, SR4 7DR Sunderland 0191 5659952 SR2 7AW Buses X24 2/A, 0191 5673399 8/A/X 16,35/A 39,78/A,135,136 3 COOPER ROSE 9 KINGS ARMS 2-4 Albion Place Beach Street , Sunderland SR1 Deptford 3NG 0191 Sunderland 5148530 SR4 6BU 0191 5679804 Buses - 8,10,11 20 73 135/136 4 DUN COW 10 LAMBTON High St West WORM Sunderland 6 Low Row SR1 3HA Sunderland 0191 5672262 SR1 3PY 191 5689910 . 5 ENGINE ROOM This guide, along with Old Fire Station, those of South Shields High St West , & Washington, can be Sunderland downloaded from our SR1 3HA website :- 0191 5947241 http://sst.camra.org.uk/w ordpress/?page_id=130 6 FITZGERALDS 12-14 Green More on next Terrace page Sunderland SR1 3PZ 0191 5670852 3 City Centre & Deptford Real Ale Pubs 11 LEGACY, 17 TIPSY COW 15 Olive Street, 32 Bridge St. -

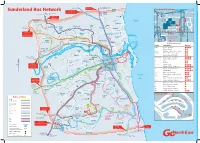

Sunderland Network Map.Ai

9 to Boldon, Jarrow 20, 20A, X20 to Cleadon Moor Lane and South Shields and North Shields WEARMOUTH South Sunderland City Centre BRIDGE S . h d i Bents e R Sunderland Bus Network Sunderland l s WAY d Y’S W t MAR EST WEAR S s n ST. TREET 20 LIVING T Dene e STONE Greyhound Stadium R S B O A X36 to Boldon, Gateshead Nine R D 01 o n 20A D r W a Police and Newcastle e Estate u R to Boldon ll d 35, 35A s b G t a i rd X20 FO ens h Empire 9 35 D W E BRIDGE ST. Morrisons Theatre B Hylton Lane HIGH STREET WEST HIGH STREET WEST Newcastle Do Kingsway Road ve 14 H da y R le l oa T t R Crowtree 15 o d o d E 13 n a a A d Ro Whitburn E Town End s Leisure L ls d N t an a o el 16 12 n e yk Bridges w n D Bay Centre Farm e c C a Shopping re King s 17 N STR swa t s y l c Seaburn H Ro e e Centre B O a a n x d R t 18 J o d W te oa Sunderland 35A r a R a h d Se Seaburn i R Carley t 19 FAWCETT STREET FAWCETT b Railway Station 35 o e Witherwack u a WAY MICHAEL’S ST. 56, N56 u r d BROUGHAM STREET ATHENAEUM ST. n n X36 Hylton T Downhill e Hill to Concord d S a v e Road Fulwell Ro ick Wiltshir ion R 20 t A w K a o and Newcastle ns St ru B Red Mill a Fulwell k d R IC a X36 d H Ro a r R y v a BLANDFORD STREET 21 08 B l e E Em X36 P t e n a Ra sw PLACE o si m x s House de Road s W d. -

COUNTY DURHAM a N 50 Gateshead L H

. D D T Scotswood W D S G E R D D ST. D O B E A W R R To — Carr N N E Nexus O W E S E B A L L A T E A L A N E M O G I Baltic HEBBURN 89 Monkton T D A TE G G Y R O O S U O O G S Jarrow and R A N Ellison O T D LAWRENCE I House R C Millennium R 88 O M S St. Anthony’s R Law T Hall A E N C Centre R K T NEW TOWN Hebburn K R A D N E Park 87 E R I A R R C W G O R R O For details of bus services E S Courts S Bridge LT M E A Park Lightfoot I E D T D N E G A 27 A N A T K E Y S O T L O D E W W N N R I A T in this area G O E E U S A L A A B A T O T K Adelaide D T T Q H N R E R S D see the C N O M O A E T T A R O HEBBURN E C E O A N ST. Y PO Newcastle guide Centre R T R D D B A S C N E Y PO G D Hebburn E E T A M B&Q L Q1 N L L S G A O D ’ ANTHONY’S I D I L S P N E V B L R O D A I T A R M D O H B S T R R R R W A O R S S N G A K Q1 93 E R O A D O E L S W I C I K S O D O E L R SAGE Q E R Newcastle W L G 94 A D U T ST. -

Map of Car Parks in the City Centre

A6 N 9, A E C 69 LA 6) TOWN MOOR . R R D EM A D O ON R T : \ . ND R To Ashington (A189) OA To Jesmond O D and Gosforth and hotels SM .--· JE ····· """ Royal Jesmond To Ponteland, Jedburgh & Airport Morpeth, Scotland (A1), Hexham (A1, A69) Skateboard Grammar P park School O O A167(M) 8 R R. 05 S K TE T 1 B C 6 E A A L K O L R N R A A A S C R P R N E I University M N H N D O G W N of Newcastle INDSO T B T R E T T TER E O O . upon Tyne R C . N L Medical R D T E D T R A C School R E O C D 1 R B C E 1 A B A D E C D R D . OA FO 2 University R Y 2 Dental Library 24 SAND Hospital Museum of D ON 0) 07 The Hatton GalleryGreat North 16 M -7 13 and Shefton Museum S . 1 B Museum JE os CASTLE LEAZES Royal Victoria (N 31 Infirmary D Antiquities, D A A St. Georges O O R 28 R A 18 I 5 K D R R L University of I A 29 R C O S Northumbria H T W O Northern Stage A at Newcastle A C F R I R Y D V R S Civic D O A S B Centre N N N City G University of BRIDGE A E N Stadium R I Newcastle S University O E K upon Tyne A U Gallery D Q St. -

SP.31 Sunderland Transforming Our City

SUNDERLAND Transforming Our City The 3,6,9 Vision SUNDERLAND Transforming Our City The 3,6,9 Vision TRANSFORMING OUR CITY Sunderland is a place that is changing, reinventing itself Sunderland did not fare well in the world economic and being transformed from a great industrial 20th recession that began in 2008. As a city with a major century town to a modern vibrant and prosperous 21st economic dependence on world trade, the downturn in century city. global demand for manufactured products such as cars hit us hard and it is only over the last couple of years From a giant of the steam age when our coal powered that we are seeing an upturn in the number of jobs and the industrial revolution and ships built on the the number of businesses in the city. Wear sailed around the world it is becoming once again an economic powerhouse, but now as a great With a population of just over 275,000, the city has manufacturing city producing cars that are driven across about 120,000 jobs and an unemployment rate of 8.3% the world, creating software for the digital age that is against a national rate of 5.4%. While most parts of used throughout the world and positioning itself at the the country have returned to pre-recession levels of heart of a low carbon economy, that will hopefully help jobs and unemployment, Sunderland still lags behind. save the world. However the growth in the number of businesses in the city, 6,500, the city’s Gross Value Added (GVA) output at Sunderland is a city that makes things the world wants just over £5bn and a GVA per head of population at over to buy, a city that innovates and creates and a city with £18,500 do indicate a upturn in our economic fortunes. -

Waterside House Is Located on Sunderland Enterprise Park to the West of Sunderland City Centre

WATERSIDEWATERSIDE FOR SALE / TO LET HOUSE High Quality Grade A Office building providing 36,718 sq ft HOUSE Sunderland Enterprise Park, Wearfield, SunderlandSR5 2TZ LOCATION Waterside House is located on Sunderland Enterprise Park to the west of Sunderland City Centre. Sunderland is approximately 12 miles south east of Newcastle upon Tyne and approximately 13 miles north east of Durham. Sunderland is well connected with easy access to both the A19 and A1(M) and Sunderland rail station connecting to Newcastle, Durham and London Kings Cross. The Tyne & Wear Metro links to Newcastle city centre and on to Newcastle International Airport. WATERSIDE HOUSE Stadium of Light Sunderland City Centre Pallion Retail Park WATERSIDE Northern Spire A1231 HOUSE Wessington Way RIVER WEAR Sainsbury Superstore DW Fitness Gym SITUATION Waterside House is situated to the north side of Local occupiers include: the River Wear, only 2 miles west of Sunderland Hylton Riverside Retail Park – Argos Extra, B&M, Pets at Home, City Centre, and a short distance from the new Matalan, Sainsbury Superstore, Northern Spire bridge crossing. Sunrise Enterprise Park and Southwick Industrial Estate. The A1231 Wessington Way, which lies immediately to the north of the There is also a DW Fitness First property, is considered to be the main arterial route to the city centre and Gym in the local vicinity. links to both the A19 and A1(M). WATERSIDE HOUSE ACCOMODATION The available accommodation provides the following net internal areas: ACCOMMODATION SQ M SQ FT Second Floor 1,138.38 12,253 First Floor 1,136.85 12,237 Ground Floor 1,135.99 12,228 TOTAL 3,411.22 36,718 The accommodation is available either as a whole or on a floor by floor basis. -

Core Strategy and Development Plan Infrastructure Delivery Plan Updated December 2018

Core Strategy and Development Plan Infrastructure Delivery Plan Updated December 2018 Planning Policy Section Sunderland City Council Civic Centre Sunderland SR2 7DN 0191 561 1574 [email protected] Urban Vision Partnership Ltd. Civic Centre Chorley Road Swinton Salford M27 5AS Document History Revision ref Amendments Date issued Early Draft Infrastructure 14 October 2016 Delivery Plan v0.1 Draft Infrastructure Delivery 07 July 2017 Plan v0.1 Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.1 (7 July 2017) 25 July 2017 Plan v0.2 Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.2 (25 July 2017) 27 July 2017 Plan v0.3 Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.3 (7, 14 & 15 19 March 2018 Plan v0.4 March 2018) Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.4 (following 4 May 2018 Plan v0.5 external comments received in April 2018) Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.5 16 May 2018 Plan v0.6 Draft Infrastructure Delivery Client feedback on v0.6 4 June 2018 Plan v0.7 Notice This report has been prepared for the exclusive use of Sunderland City Council and unless otherwise agreed in writing by Sunderland City Council or Urban Vision Partnership Ltd, no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of the report. No liability is accepted by Urban Vision Partnership Ltd for any use of this report, other than the purposes for which it was originally prepared and provided. Opinions and information provided in the report are on the basis of Urban Vision Partnership Ltd using due skill, care and diligence in preparation of the same and no explicit warranty is provided as to their accuracy. -

Sunderland: the Challenges of the Future

Sunderland: The Challenges of the Future A report prepared by Centre for Cities for Sunderland City Council January 2009 Dr Malcolm Cooper Introduction Sunderland is a Partner City in the Centre for Cities research programme ‘Unlocking City Potential and Sustaining City Growth’. The programme works closely with a small group of cities to inform economic development strategies and improve economic performance. This report sets out policy analysis and recommendations in response to two principal questions: • How can Sunderland build on a decade of achievement to attain long-term sustainable growth? • What should be the main priorities in formulating an appropriate economic development strategy? Sunderland Great Britain Other services Manufacturing 10.6% 1.1% Manufacturing Other services 2.3% 14.9% Construction 4.9% Public administration, Construction education & health Wholesale activities 4.2% 5.0% 30.5% Wholesale activites 2.5% Public administration, education & health Retail & leisure 26.9% 22.1% Retail & Leisure 20.1% Research, architecture & ofce services Transport & communication 5.1% Research, architecture & 5.9% Transport & communications office services Agriculture & energy Financial & Related 4.7% 6.1% 1.6% Business Services Financial & Related Agriculture & energy 14.2% Business Services 1.9% 15.6% Source: NOMIS 2008 Annual Business Inquiry Employee Analysis (ABI) for 2007 data. Key Recommendations • The phased regeneration of the city centre must be pursued for Sunderland’s economy to return to its recent growth trajectory. • The Working Neighbourhoods Strategy should be pursued along with the introduction of an integrated bus network to bind Sunderland into the wider city region economy. • Policy and financial resources should be invested to create the infrastructure for a local enterprise and innovation network.