Manuel-Riesco-Is-Pinochet-Dead.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

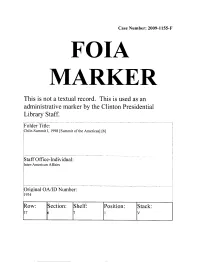

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the Chnton Presidential Library Staff

Case Number: 2009-1155-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the CHnton Presidential Library Staff. Folder Title: Chile-Summit I, 1998 [Summit of the Americas] [6] Staff Office-Individual: Inter-American Affairs Original OA/ID Number: 1934 Row: Section: Shelf: Position: Stack: 37 6 7 1 V THE WHITE HOUSE WASH INGTON April 10, 1998 MEMORANDUM TO JOHN PODESTA MACK McLARTY JIM STEINBERG GENE SPERLING FROM: THURGOOD MARSHALL, JR. KRIS BALDERSTON ,,yl^ SUBJECT: CABINET PARTICIPATION IN THE CHILE TRIP UPDATE The following attachment is an updated version of the schedule for the Cabinet's participation in the President's trip to Santiago, Chile. Please contact us if you have any questions. Attachment cc: David Beaubaire Nelson Cunningham Nichole Elkon Laura Graham Sara Latham Laura Marcus Elisa Millsap Janet Murguia Ted Piccone Jaycee Pribulsky Steve Ronnel Cabinet Schedules SUMMIT OF THE AMERICAS-SANTIAGO, CHILE ARIL 1998 Time POTUS Schedule Time Cabinet Schedule WEDNESDAY. APRIL 15TH 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route Santiago 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route [flight time: 10 hours, 15 minutes] Santiago [time change: none] Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey depart RON AIR FORCE ONE RON A IR FORCE ONE THURSDAY APRIL 16TH 7:00 am Arrive Santiago 7:00 Arrive Santiago Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey arrive 7:10 am- Arrival Ceremony 7:10- Arrival Ceremony 7:25 am TARMAC 7:25 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky Santiago Airport McCaffrey attend Open Press 8:00 am Arrive Hyatt Regency Hotel 8:00 am- Down Time 9:30 am Hyatt Regency Hotel 10:25 am- State Arrival Ceremony 10:25- State Arrival Ceremony 10:35 am Courtyard - La Moneda Palace 10:35 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, Press TBD McCaffrey attend 10:35 am- Restricted Bilateral with President Frei 11:25 am President's Office - La Moneda Palace Official Photo Only Note: Potus plus 5. -

REPORT No. 138/18 PETITION 687-11 FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS and C.B.B.1 CHILE NOVEMBER 21, 20182

OEA/Ser.L/V/II. REPORT No. 138 /18 Doc. 155 21 November 2018 PETITION 687- 11 Original: Spanish FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT REPORT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS AND HER DAUGHTER C.B.B. CHILE Elctronically approved by the Commission on November 21, 2018. Cite as: IACHR, Report No. 138/ 18, Petition 687-11. Friendly Settlement G.B.B. and C.B.B. November 21, 2018 . www.cidh.org REPORT No. 138/18 PETITION 687-11 FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS AND C.B.B.1 CHILE NOVEMBER 21, 20182 I. SUMMARY AND PROCEDURAL CONSIDERATIONS RELATED TO THE FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT PROCEEDINGS BEFORE THE IACHR 1. On May 15, 2011, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or “the IACHR”) received a petition lodged by the Humanas Corporation Regional Human Rights and Gender Justice Center and the Observatory on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, alleging the international responsibility of the Chilean State (hereinafter “the State” or “the Chilean State”) for the alleged violation of Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights), Article 2 (domestic legal effects), Article 5 (right to humane treatment), Article 7 (right to personal liberty), Article 8.1 (right to a fair trial), Article 17 (rights of the family), Article 19 (rights of the child), Article 24 (right to equal protection), Article 25 (right to judicial protection), and Article 26 (progressive development) of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention” or “the American Convention”), and for violating Articles 7 (a) and (b), 8, 9, and 26 of the Convention of Belem do Para, with respect to Gabriela Blas and her daughter C.B.B. -

Open Letter to Them

You can help Alice Dear Readers, now you know the story of Alice and her friends. If you want to inform other people about Project Infinity = the MICT-Study = the MDMA In Couples Therapy-Study, you can use the following Letter to Decision Makers. You can download this letter from our website: www.alicetoday.eu This information on Project Infinity can also be sent to politicans, to media-people and to all other decision- makers you can think of. Included you find some international addresses of heads of state and of some media people, if you want to send the Open Letter to them. All of these addresses can be found in the Internet, plus many additional ones, as there are around 200 states on Earth. Just write to those Heads of State, who are important to you. Thank you for your support! Letter to Decision Makers Place/ Date:……................................…………….. Dear Mrs./ Mr. ..................................................................................................... this is an Open Letter on the MDMA in Couples-Therapy-Study or MICT-Study. Key-Words 1.) Ethical standards in medicine and psychotherapy? 2.) PAS = Psycho-Actice Substances in medicine and psychotherapy 3.) The MICT-Study = MDMA in Couples-Therapy-Study 4.) Re-gained empathy 5.) Re-gained intimacy 6.) Re-gained self-confidence and communication with the partner/ spouse, the family, at work, at social occasions etc. 7.) Open-hearted, playful, quiet and wider erotic experience 8.) Female polyorgiastic intimacy 9.) Male polyorgiastic intimacy Results a) Side-effects b) Results of the MICT-experience itself c) For the couple: evaluation of the personal outcome of MICT after: 4 weeks/ 3 month/ 6 month/ 1 year/ 3 years (and, as far as possible 5 years/ 10 years) d) For the family = for the exchange with children/ parents etc. -

Unfinished Timelines Chile, First Laboratory of Neoliberalism

March 21 – May 24, 2019 Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Library and Documentation Centre March 21 – May 24, 2019 Nouvel Building Library opening hours Nouvel Building, Library, Space D Ronda de Atocha s/n Monday to Friday 28012 Madrid from 9:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. Except holidays Tel. (+34) 91 774 10 00 Unfinished Timelines The exhibition room will be vacated 15 minutes before closing time Chile, First Laboratory www.museoreinasofia.es Tel. (+34) 91 774 10 27 of Neoliberalism Related activities Gallery conversation Feminist occupation of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, Santiago de Chile, by Nelly Richard May 2018 March 26 at 7 p.m. Pre-registration required 20 places available to fabricate docile subjectivities. This feminist insurgency not only shook up the patriarchal architecture of the Seminar institutional powers (religious, cultural, social, and political) Chile: las operaciones críticas that had dictated the form taken by the Chilean transition, de la memoria, by Nelly Richard it also propagated the seeds of a libertarian impulse to March 25 and 26 at 11 a.m. Nouvel Building, Study Centre collectively experience a world breaking free of its chains. Pre-registration required One of the banners that appeared during the May 2018 35 places available occupation of Santiago’s Pontifical Catholic University of Chile—a university whose School of Economics turned Encounter Cuerpos y memorias de la neoliberalism into a dogma—declared: “The Chicago Boys transición en América Latina y are shaking. The feminist movement endures.” This feminist España: relecturas feministas slogan reminds us that it’s never too late for emancipatory Roundtable with Maite Garbayo, impulses to break up a neoliberal hegemony (in this case, Ana Longoni, Nelly Richard, that of the Chicago Boys) established more than forty years and Clara Serra earlier, and to appeal to a future that can only come about March 27 at 7 p.m. -

Nelly Richard's Crítica Cultural: Theoretical Debates and Politico- Aesthetic Explorations in Chile (1970-2015)

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015) https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40178/ Version: Full Version Citation: Peters Núñez, Tomás (2016) Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015). [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London Nelly Richard's crítica cultural: Theoretical debates and politico- aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970-2015) Tomás Peters Núñez Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2016 This thesis was funded by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Ministerio de Educación, Chile. 2 Declaration I, Tomás Peters Núñez, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Date 25/January/2016 3 ABSTRACT This thesis describes and analyses the intellectual trajectory of the Franco- Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard between 1970 and 2015. Using a transdisciplinary approach, this investigation not only analyses Richard's series of theoretical, political, and essayistic experimentations, it also explores Chile’s artistic production (particularly in the visual arts) and political- cultural processes over the past 45 years. In this sense, it is an examination, on the one hand, of how her critical work and thought emerged in a social context characterized by historical breaks and transformations and, on the other, of how these biographical experiences and critical-theoretical experiments derived from a specific intellectual practice that has marked her professional profile: crítica cultural. -

Salvador Allende- Notes on His Security Team: the Group of Personal Friends (Gap-Grupo De Amigos Personales)

STUDY SALVADOR ALLENDE- NOTES ON HIS SECURITY TEAM: THE GROUP OF PERSONAL FRIENDS (GAP-GRUPO DE AMIGOS PERSONALES) Cristián Pérez This article describes the formation and development of the first strictly revolutionary institution of the Socialist President Salvador Allende: his security team, known as the Group of Personal Friends or GAP, from its origins in 1970 to the fight at the Presidential Palace (La Moneda). In it I intend to trace the different phases of the organisation, the diversity of its functions and its intimate rela- tionships with, on the one hand, the parties and movements of the Chilean Left and, on the other, with Cuba. CRISTIÁN PÉREZ is studying for his Master´s degree at the University of Santia- go in Chile. Estudios Públicos, 79 (winter 2000). 2 ESTUDIOS PÚBLICOS “Salvador always goes everywhere with his personal bodyguards” (Laura Allende)1 INTRODUCTION2 A t one o´clock in the morning of Tuesday September 11th, the 20 young men who were on guard at the President´s rest house, known as El Cañaveral, in the upper class area of Santiago, were finishing their traditio- nal game of pool when they heard the voice of “Bruno”, the head of the President´s security team, who ordering them to go to their dormitories. The news that he brought about the national situation did not cause any undue anxiety, because over the past few months rumours of a coup against the Government had become almost routine, especially after June 29th, the day of the tanks or el tancazo as it was known.3 At the same time, some kilome- tres towards the centre of the capital, in the house at Tomas Moro No. -

The Patagonian Adventure in Chile and Argentina

GROUP TRAVEL SAE 2134 PRICE PER PERSON IN DOUBLE OCCUPANCY THE PATAGONIAN ADVENTURE USD 3.552.- EUR 2.950.- Surplus single occupancy IN CHILE AND ARGENTINA USD 897.- EUR 745.- SET DEPARTURES 13 days / 12 nights 2021 2022 11 September 16 April Patagonia is the region at the southern end of South America shared by Argentina and Chile. On 16 October 06 May this region you will find Andes Mountains, lakes, fjords and glaciers as well as deserts, 30 October 17 September tablelands and steppes. The name Patagonia comes from the word patagón. Magellan used 13 November 22 October 12 November this term in 1520 to describe the native tribes of the region, whom his expedition thought to be giants. The people he called the Patagons are now believed to have been the Tehuelche, who INCLUDED SERVICES ✓SIB (Sit-in-basis) for transfers, sightseeing tours tended to be taller than Europeans of the time. and connections Patagonia is one of the most interesting placers in South America and is thought to be kept as ✓12 nights in selected hotels including natural as possible, therefore, all efforts made to reach this goal, make tourism a bit expensive ✓12 breakfasts, 8 lunches, 4 dinners including but worth a visit. • 1 dinner and tango show in Buenos Aires • 1 Fiesta Gaucha with lunch in Santa Susana WE will start our visit in Santiago de Chile getting prepared for this amazing adventure. Fly to ✓Boat ride and hiking in glaciers Punta Arenas, the gate to the Chilean Patagonia and start your journey visiting its glaciers and ✓All excursions and transfers mentioned in the lakes. -

Arrive in Buenos Aires Itinerary for Best of Argentina To

Expat Explore - Version: Tue Sep 28 2021 16:19:10 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/24 Itinerary for Best of Argentina to Peru - Tour Buenos Aires to Lima • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Hotel in Buenos Aires, Hotel in Lima, Address to be confirmed Address to be confirmed Welcome meeting at 18:00 hrs 10:00 hrs DAY 1: Arrive in Buenos Aires Welcome to your South American tour! The first stop is Buenos Aires, Argentina’s cosmopolitan capital city. Arrive and check into the hotel. Head out and get your first taste of the city if you arrive with time to spare. This evening, meet your tour leader and group in the hotel lobby at 18:00. Once everyone is together, head out to a nearby local restaurant for the first group dinner of the tour. Experiences Buenos Aires Dinner. Enjoy your first meal in Argentina! The cuisine here has been heavily influenced by waves of European migration over the last century and often includes dishes with Spanish, Italian and German roots. Grilled meats, pastas, empanadas and sweet desserts are widely offered. How about a glass of Argentinian wine to complement your first meal in the country? Expat Explore - Version: Tue Sep 28 2021 16:19:10 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/24 Included Meals Accommodation Breakfast: Lunch: Dinner: Imperial Park Hotel DAY 2: Buenos Aires City Tour Take a tour of Buenos Aires’s vibrant streets with an expert local guide this morning. Art, architecture, history, cuisine, culture… Buenos Aires has it all! Follow your guide and see the city’s highlights. -

Arrive in Santiago Itinerary for Chile to Peru Explorer

Expat Explore - Version: Wed Sep 29 2021 10:31:39 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/20 Itinerary for Chile to Peru Explorer - Tour Santiago to Lima • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Hotel in Santiago, Hotel in Lima, Address to be confirmed Address to be confirmed Welcome meeting at 18:00 hrs 10:00 hrs DAY 1: Arrive in Santiago Bienvenido en Santiago! Welcome to Santiago! Spend the day exploring if you arrive early enough, and then meet your tour leader at 18:00 hrs at the hotel for a welcome meeting. Then head out for a meet & greet dinner with fellow travellers and your tour leader this evening. Tomorrow you have a full day to explore the city of Santiago. Experiences Welcome dinner. This welcome dinner is the ideal opportunity to sample your first Chilean meal and get acquainted with your tour mates. These fine folks will be adventuring alongside you for the next 18 days, so buddy up! Expat Explore - Version: Wed Sep 29 2021 10:31:39 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/20 Included Meals Accommodation Breakfast: Lunch: Dinner: Hotel Providencia Panamericana DAY 2: Santiago City Tour Get ready to explore Santiago. Grab breakfast and follow a local guide into the heart of the Chilean city. Discover the downtown area, the famous Alameda main avenue, and the Plaza de Armas. Not to mention the Central Market and Santiago Cathedral. Also tick off the bohemian Bellavista district and San Cristobal Hill. Make your own way after lunch. Join in on an optional group dinner at a local restaurant this evening if you're keen. -

Chapter V Jurisdiction Over Crimes Under International Law

DIGEST OF LATIN AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE ON INTERNATIONAL CRIMES r Due Process of Law Foundation Washington, DC Due Process of Law Foundation 1779 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Suite 510A Washington, DC 20036 www.dplf.org © 2010 Due Process of Law Foundation All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-9827557-0-9 This volume was published with financial support from theUnited States Institute for Peace (USIP). The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are exclusively those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USIP. CONTENrTS Foreword by Naomi Roht-Arriaza ............................................................................................................ ix Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................... xv Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. xvii List of Judgments ....................................................................................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................. xli Chapter I Crimes under International Law .............................................................................................................. 1 Chapter II Individual Criminal Responsibility and Forms -

Patrimoine Mondial 28 COM

Patrimoine mondial 28 COM Distribution limitée WHC-04/28.COM/14A Paris, 24 mai 2004 Original : anglais/français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Vingt-huitième session Suzhou, Chine 28 juin – 7 juillet 2004 Point 14 de l'ordre du jour provisoire: Listes indicatives des Etats parties soumises au 15 mai 2004 en conformité avec les Orientations. RESUME Ce document présente les Listes indicatives de tous les Etats parties, soumises à la date du 15 mai 2004 conformément avec les Orientations. Il est demandé au Comité de noter que tous les biens devant être étudiés par le Comité à sa 28e session, sont inclus dans les Listes indicatives des Etats parties respectifs. Afin d’offrir au Comité la possibilité de passer en revue les nouveaux ajouts aux Listes indicatives, ce document est complété par trois annexes : •= L’annexe 1 présente une liste complète des Etats parties indiquant la date de la plus récente Liste indicative ; •= L’annexe 2 présente les nouvelles Listes indicatives (ou les ajouts aux Listes indicatives existantes) soumises par les Etats parties depuis la dernière session du Comité ; •= L’annexe 3 présente une liste de tous les biens inclus dans les Listes indicatives des Etats parties classés par ordre alphabétique anglais. Les noms des biens figurent dans la langue dans laquelle les Etats parties les ont soumis. Projet de décision 28 COM 14A : voir page 2 Examen des Listes indicatives 1. Le Comité demande à chaque Etat partie de lui soumettre un inventaire des biens culturels et naturels situés sur son territoire, dont l’inclusion lui semble appropriée et dont il a l’intention de proposer l’inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial dans les cinq ou dix prochaines années.