Living Through the Chilean Coup D'etat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texto Completo (Pdf)

ORIGINALES Recuerdos de hospital José Rico Irles evisando mis vivencias y para no ser Raburrido, quisiera mostrar algunos El amor de hoy casos clínicos, que no son «clínicos» o SIDA hasta la Aquí me refiero puramente médicos, sino vitales, sociales hepatitis C u a casos y casos o casos vivos. Serían muy interesantes otras enferme- que se ven a para los estudiantes de Medicina. Para dades de trans- diario. los que ya somos mayores, lo que cuen- misión sexual. Y Hace 20 años to nos puede servir de recuerdo y tal vez la respuesta en casi todas las de reflexión. La profesión médica es muy los más fieles a parejas se casa- arriesgada y en nuestros tiempos cada la pareja suele ban vírgenes. vez más. ser esta: «Yo, Alguna expe- He aquí los casos y cuestiones que aquí solo con mi no- riencia sexual recojo. via». previa pero na- ¿Qué debe ha- da más. Era ex- cer el médico cesiva la moral educacional. Aunque, ante esta situación? digan lo que digan, no funcionó mal. Creo que es muy sencillo. Sin necesi- Tener un hijo soltera era un baldón dad de aludir a factores religiosos 15 para la madre. Eso era demasiado. (hoy se huye de ello) hay que adver- Pero hoy hemos pasado al otro extre- tir de los riesgos de la relación sexual mo. Me refiero a las relaciones se- indiscriminada. Aparte el riesgo de xuales. embarazo (después vendrá la duda Ahora el amor es sinónimo de rela- ante el aborto), hay que hacer ver que ción sexual. Ahora hay que preguntar la relación sexual con diversas pare- siempre a un joven (él o ella) por las jas es fuente de posibles enfermeda- relaciones sexuales. -

Salvador Allende Rea

I Chronology: Chile 1962-1975 Sources: Appendix to Church Committee Report reproduced on the Internet by Rdbinson Rojas Research Unit Consultancy <http:// www. soft.net.uk/rrojasdatabank/index.htm> [the "Church Committee," named after its chairman Senator Frank Church, was the U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations in Respect to Intelligence Activities]; James D. Cockcroft, Latin America: History, Politics, and U.S. Policy, 2"d ed. (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing/Thomson Learning, 1997), 531-565; Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, "Chile: A Chronology," Appendix A of United States and Chile During the Allende Years, 1970-1973: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Inter-American Affairs o] the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975); Hedda Garza, Salvador Allende (New York and Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989); "HI and Chile," Report of the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations, June 21,1973; NACLA Report on the Americas, May-June 1999. 1962 Special Group [select U.S. government officials including the CIA approves $50,000 to strengthen Christian Democratic Party (PDC) subsequently approves an additional $180,000 to strengthen PDC anc its leader, Eduardo Frei. Throughout early 1960s, the U.S. Depart ment of the Army and a team of U.S. university professors develop "Project Camelot," which calls for the coordinated buildup of civilian and military forces inside Chile, with U.S. support, into a force capable of overthrowing any elected left-coalition govemment. 1963 Special Group approves $20,000 for a leader of the Radical Party (PR); later approves an additional $30,000 to support PR candidates in April municipal elections. -

Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 1-26-1996 Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation." (1996). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/12109 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 55802 ISSN: 1060-4189 Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation by LADB Staff Category/Department: Chile Published: 1996-01-26 In mid-January, police in Argentina arrested the person believed responsible for the 1974 assassination in Buenos Aires of Chilean Gen. Carlos Prats and his wife Sofia Couthbert. The individual arrested is a former Chilean intelligence agent, and his capture has brought renewed calls for the resignation of Chile's army chief, Gen. Augusto Pinochet. The case has also resurfaced tensions between the Chilean military and the civilian government of President Eduardo Frei. On Jan. 19, Argentine police in Buenos Aires arrested Enrique Lautaro Arancibia Clavel, a Chilean citizen who is suspected of being the intellectual author of the 1974 assassination of Gen. Prats and his wife. The arrest was announced by Argentine President Carlos Saul Menem, who called it "a new victory for justice and for the federal police." Police sources said Arancibia Clavel had been sought for years by Argentine, Chilean, and Italian authorities in connection with the deaths of Prats and his wife, as well as for carrying out other assassinations on behalf of the Chilean secret service (Direccion de Inteligencia Nacional, DINA). -

A History of Political Murder in Latin America Clear of Conflict, Children Anywhere, and the Elderly—All These Have Been Its Victims

Chapter 1 Targets and Victims His dance of death was famous. In 1463, Bernt Notke painted a life-sized, thirty-meter-long “Totentanz” that snaked around the chapel walls of the Marienkirche in Lübeck, the picturesque port town outside Hamburg in northern Germany. Individuals covering the entire medieval social spec- trum were represented, ranging from the Pope, the Emperor and Empress, and a King, followed by (among others) a duke, an abbot, a nobleman, a merchant, a maiden, a peasant, and even an infant. All danced reluctantly with grinning images of the reaper in his inexorable procession. Today only photos remain. Allied bombers destroyed the church during World War II. If Notke were somehow transported to Latin America five hundred years later to produce a new version, he would find no less diverse a group to portray: a popular politician, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, shot down on a main thoroughfare in Bogotá; a churchman, Archbishop Oscar Romero, murdered while celebrating mass in San Salvador; a revolutionary, Che Guevara, sum- marily executed after his surrender to the Bolivian army; journalists Rodolfo Walsh and Irma Flaquer, disappeared in Argentina and Guatemala; an activ- ist lawyer and nun, Digna Ochoa, murdered in her office for defending human rights in Mexico; a soldier, General Carlos Prats, murdered in exile for standing up for democratic government in Chile; a pioneering human rights organizer, Azucena Villaflor, disappeared from in front of her home in Buenos Aires never to be seen again. They could all dance together, these and many other messengers of change cut down by this modern plague. -

171059630010.Pdf

Psicoperspectivas ISSN: 0717-7798 ISSN: 0718-6924 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Escuela de Psicología Castillo-Gallardo, Patricia; Peña, Nicolás; Rojas Becker, Cristóbal; Briones, Génesis El pasado de los niños: Recuerdos de infancia y familia en dictadura (Chile, 1973-1989) Psicoperspectivas, vol. 17, núm. 2, 2018, pp. 1-12 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Escuela de Psicología DOI: 10.5027/Psicoperspectivas-vol17-issue2-fulltext-1180 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=171059630010 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto El pasado de los niños: Recuerdos de infancia y familia en dictadura (Chile, 1973-1989) The past of children: Memories of childhood and family in dictatorship (Chile, 1973-1989) Patricia Castillo-Gallardo1*, Nicolás Peña1, Cristóbal Rojas Becker2, Génesis Briones2 1 Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano, Santiago, Chile 2 Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile *[email protected] Recibido: 30-septiembre-2017 Aceptado: 10-julio-2018 RESUMEN En los últimos años, a propósito de las transformaciones en las representaciones de la infancia, la historia reciente ha abierto un espacio en los estudios sobre las dictaduras cívico-militares del cono sur, para investigar la experiencia de la niñez desde la mirada de sus protagonistas. En este artículo se presentan resultados en torno a los recuerdos de personas que vivieron su niñez durante la última dictadura cívico-militar chilena, específicamente en torno a los recuerdos de infancia y familia. -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

Ninagawa Company Kafka on the Shore Based on the Book by Haruki Murakami Adapted for the Stage by Frank Galati

Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 23 –26 David H. Koch Theater Ninagawa Company Kafka on the Shore Based on the book by Haruki Murakami Adapted for the stage by Frank Galati Directed by Yukio Ninagawa Translated by Shunsuke Hiratsuka Set Designer Tsukasa Nakagoshi Costume Designer Ayako Maeda Lighting Designer Motoi Hattori Sound Designer Katsuji Takahashi Hair and Make-up Designers Yoko Kawamura , Yuko Chiba Original Music Umitaro Abe Chief Assistant Director Sonsho Inoue Assistant Director Naoko Okouchi Stage Manager Shinichi Akashi Technical Manager Kiyotaka Kobayashi Production Manager Yuichiro Kanai Approximate performance time: 3 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of Kafka on the Shore is made possible in part by generous support from the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support provided by Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.), Inc., Marubeni America Corporation, Mitsubishi Corporation (Americas), Sumitomo Corporation of Americas, ITOCHU International Inc., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries America, Inc., and Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal U.S.A., Inc. Co-produced by Saitama Arts Foundation, Tokyo Broadcasting System Television, Inc., and HoriPro, Inc. LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 KAFKA ON THE SHORE Greeting from HoriPro Inc. HoriPro Inc., along with our partners Saitama Arts Foundation and Tokyo Broadcasting System Television Inc., is delighted that we have once again been invited to the Lincoln Center Festival , this time to celebrate the 80th birthday of director, Yukio Ninagawa, who we consider to be one of the most prolific directors in Japanese theater history. -

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

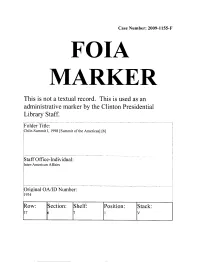

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the Chnton Presidential Library Staff

Case Number: 2009-1155-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the CHnton Presidential Library Staff. Folder Title: Chile-Summit I, 1998 [Summit of the Americas] [6] Staff Office-Individual: Inter-American Affairs Original OA/ID Number: 1934 Row: Section: Shelf: Position: Stack: 37 6 7 1 V THE WHITE HOUSE WASH INGTON April 10, 1998 MEMORANDUM TO JOHN PODESTA MACK McLARTY JIM STEINBERG GENE SPERLING FROM: THURGOOD MARSHALL, JR. KRIS BALDERSTON ,,yl^ SUBJECT: CABINET PARTICIPATION IN THE CHILE TRIP UPDATE The following attachment is an updated version of the schedule for the Cabinet's participation in the President's trip to Santiago, Chile. Please contact us if you have any questions. Attachment cc: David Beaubaire Nelson Cunningham Nichole Elkon Laura Graham Sara Latham Laura Marcus Elisa Millsap Janet Murguia Ted Piccone Jaycee Pribulsky Steve Ronnel Cabinet Schedules SUMMIT OF THE AMERICAS-SANTIAGO, CHILE ARIL 1998 Time POTUS Schedule Time Cabinet Schedule WEDNESDAY. APRIL 15TH 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route Santiago 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route [flight time: 10 hours, 15 minutes] Santiago [time change: none] Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey depart RON AIR FORCE ONE RON A IR FORCE ONE THURSDAY APRIL 16TH 7:00 am Arrive Santiago 7:00 Arrive Santiago Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey arrive 7:10 am- Arrival Ceremony 7:10- Arrival Ceremony 7:25 am TARMAC 7:25 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky Santiago Airport McCaffrey attend Open Press 8:00 am Arrive Hyatt Regency Hotel 8:00 am- Down Time 9:30 am Hyatt Regency Hotel 10:25 am- State Arrival Ceremony 10:25- State Arrival Ceremony 10:35 am Courtyard - La Moneda Palace 10:35 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, Press TBD McCaffrey attend 10:35 am- Restricted Bilateral with President Frei 11:25 am President's Office - La Moneda Palace Official Photo Only Note: Potus plus 5. -

The-Vandal.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMPSON artistic director CAROL OSTROW producing director BETH DEMBROW managing director presents the world premiere of THE VANDAL written by HAMISH LINKLATER directed by JIM SIMPSON DAVID M. BARBER set design BRIAN ALDOUS lighting design CLAUDIA BROWN costume design BRANDON WOLCOTT sound design and original music MICHELLE KELLEHER stage manager EDWARD HERMAN assistant stage manager CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) Man...........................................................................................................................Zach Grenier Woman...............................................................................................................Deirdre O’Connell Boy...........................................................................................................................Noah Robbins CREATIVE TEAM Playwright...........................................................................................................Hamish Linklater Director.......................................................................................................................Jim Simpson Set Design..............................................................................................................David M. Barber Lighting Design.........................................................................................................Brian Aldous Costume Design......................................................................................................Claudia Brown Sound Design and Original -

Appetite for Autumn 34Th Street Style Knicks & Nets

NOV 2014 NOV ® MUSEUMS | Knicks & Nets Knicks 34th Street Style Street 34th Restaurants offering the flavors of Fall NBA basketball tips-off in New York City York New in tips-off basketball NBA Appetite For Autumn For Appetite Styles from the world's brands beloved most BROADWAY | DINING | ULTIMATE MAGAZINE FOR NEW YORK CITY FOR NEW YORK MAGAZINE ULTIMATE SHOPPING NYC Monthly NOV2014 NYCMONTHLY.COM VOL. 4 NO.11 44159RL_NYC_MONTHLY_NOV.indd All Pages 10/7/14 5:18 PM SAMPLE SALE NOV 8 - NOV 16 FOR INFO VISIT: ANDREWMARC.COM/SAMPLESALE 1OOO EXCLUSIVES • 1OO DESIGNERS • 1 STORE Contents Cover Photo: Woolworth Building Lobby © Valerie DeBiase. Completed in 1913 and located at 233 Broadway in Manhattan’s financial district, The Woolworth building is an NYC landmark and was at the time the world’s tallest building. Its historic, ornate lobby is known for its majestic, vaulted ceiling, detailed sculptures, paintings, bronze fixtures and grand marble staircase. While generally not open to the public, this neo-Gothic architectural gem is now open for tours with limited availability. (woolworthtours.com) FEATURES Top 10 things to do in November Encore! Encore! 16 26 Feel the energy that only a live performance in the Big Apple can produce 34th Street Style 18 Make your way through this stretch of Midtown, where some of the biggest outposts from global NYC Concert Spotlight brands set up shop 28 Fitz and the Tantrums Appetite For Autumn 30 The Crowd Goes Wild 20 As the seasons change, so do these restaurant's NBA basketball tips off in NYC menus, -

Análisis De La Reputación De Chile En La Prensa Extranjera 2015

ANÁLISIS DE LA REPUTACIÓN DE CHILE EN LA PRENSA EXTRANJERA 2015 Ricardo Leiva Doctor en Comunicación Universidad de Navarra Tatiana Berckhoff Cádiz Facultad de Comunicación Universidad de Navarra Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de los Andes Av. San Carlos de Apoquindo 2.200 Teléfono 22 618 1245 – [email protected] 1 ANÁLISIS DE LA REPUTACIÓN DE CHILE EN LA PRENSA EXTRANJERA 2 ANÁLISIS DE LA REPUTACIÓN DE CHILE EN LA PRENSA EXTRANJERA Resumen Ejecutivo Un análisis cuantitativo y cualitativo de 1.744 artículos publicados sobre Chile en 10 diarios y 1 semanario de relevancia mundial durante 2015, muestra que los conflictos y escándalos políticos y empresariales—como el de la colusión del papel higiénico—y los litigios limítrofes con Perú y Bolivia, dañaron la reputación de Chile en el extranjero durante 2015. La buena actuación de Chile en la Copa América, en cambio, sirvió para paliar el gran número de noticias negativas que se escribieron sobre nuestro país el año pasado. Fue precisamente la Copa América el tema que resultó más interesante para la prensa extranjera durante 2015, seguido de los desastres naturales y accidentes, como las erupciones de volcanes como el Calbuco, y las inundaciones en el norte durante el primer trimestre, entre otros. Los triunfos de la Selección chilena de Fútbol se tradujeron en un volumen considerable de noticias positivas para Chile, las que fueron parcialmente contrarrestadas por la detención de Arturo Vidal tras su accidente en estado de ebriedad, y el comportamiento antideportivo de Gonzalo Jara. En 2015, el 39% de las noticias publicadas en 10 diarios y 1 semanario de referencia mundial fueron negativas para nuestro país, comparadas con el 33% que fueron positivas y el 28% que fueron neutras / mixtas.