British Christianity During the Roman Occupation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Arthur and Medieval Knights

Renata Jawniak KING ARTHUR AND MEDIEVAL KNIGHTS 1. Uwagi ogólne Zestaw materiałów opatrzony wspólnym tytułem King Arthur and Medieval Knights jest adresowany do studentów uzupełniających studiów magisterskich na kierun- kach humanistycznych. Przedstawione ćwiczenia mogą być wykorzystane do pracy z grupami studentów filologii, kulturoznawstwa, historii i innych kierunków hu- manistycznych jako materiał przedstawiający kulturę Wielkiej Brytanii. 2. Poziom zaawansowania: B2+/C1 3. Czas trwania opisanych ćwiczeń Ćwiczenia zaprezentowane w tym artykule są przeznaczone na trzy lub cztery jednostki lekcyjne po 90 minut każda. Czas trwania został ustalony na podstawie doświadcze- nia wynikającego z pracy nad poniższymi ćwiczeniami w grupach na poziomie B2+. 4. Cele dydaktyczne W swoim założeniu zajęcia mają rozwijać podstawowe umiejętności językowe, takie jak czytanie, mówienie, słuchanie oraz pisanie. Przy układaniu poszczegól- nych ćwiczeń miałam również na uwadze poszerzanie zasobu słownictwa, dlatego przy tekstach zostały umieszczone krótkie słowniczki, ćwiczenia na odnajdywa- nie słów w tekście oraz związki wyrazowe. Kolejnym celem jest cel poznawczy, czyli poszerzenie wiedzy studentów na temat postaci króla Artura, jego legendy oraz średniowiecznego rycerstwa. 5. Uwagi i sugestie Materiały King Arthur and Medieval Knights obejmują pięć tekstów tematycznych z ćwiczeniami oraz dwie audycje z ćwiczeniami na rozwijanie umiejętności słucha- nia. Przewidziane są tu zadania na interakcję student–nauczyciel, student–student oraz na pracę indywidualną. Ćwiczenia w zależności od poziomu grupy, stopnia 182 IV. O HISTORII I KULTURZE zaangażowania studentów w zajęcia i kierunku mogą być odpowiednio zmodyfiko- wane. Teksty tu zamieszczone możemy czytać i omawiać na zajęciach (zwłaszcza z grupami mniej zaawansowanymi językowo, tak by studenci się nie zniechęcili stopniem trudności) lub część przedstawionych ćwiczeń zadać jako pracę domo- wą, jeżeli nie chcemy poświęcać zbyt dużo czasu na zajęciach. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Beli Mawr Beli Mawr LLud Caswallon [1] [2] [2] [1] Penardun Llyr Adminius Llyr Penardun [3] Bran the [3] Bran the Blessed Blessed [4] [4] Beli Beli [5] [5] Amalech Amalech [6] [7] [6] [7] Eudelen Eugein Eudelen Eugein [8] [9] [8] [9] Eudaf Brithguein Eudaf Brithguein [10] [11] [10] [11] Eliud Dyfwyn Eliud Dyfwyn [12] [13] [12] [13] Outigern Oumun Outigern Oumun [14] [15] [14] [15] Oudicant Anguerit Oudicant Anguerit [16] [17] [16] [17] Ritigern Amgualoyt Ritigern Amgualoyt [18] [19] [18] [19] Iumetal Gurdumn Iumetal Gurdumn [20] [21] [20] [21] Gratus Dyfwn Gratus Dyfwn [22] [23] [22] [23] Erb Guordoli Erb Guordoli [24] [25] [24] [25] Telpuil Doli Telpuil Doli [26] [27] [26] [27] Teuhvant Guorcein Teuhvant Guorcein [28] [29] [28] [29] Tegfan Cein Tegfan Cein [30] [31] [30] [31] Guotepauc Tacit Guotepauc Tacit [32] Coel [33] [34] [32] Coel [33] [34] Hen Ystradwal Paternus Hen Ystradwal Paternus [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] Gwawl Cunedda Garbaniawn Ceneu Edern Gwawl Cunedda Garbaniawn Ceneu Edern [40] Dumnagual [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [36] [35] [40] Dumnagual [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [36] [35] Moilmut Gurgust Ceneu Masguic Mor Pabo Cunedda Gwawl Moilmut Gurgust Ceneu Masguic Mor Pabo Cunedda Gwawl [46] Bran [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] Tybion ap [58] Edern ap [59] Rhufon ap [60] Dunant ap [61] Einion ap [62] Dogfael ap [63] Ceredig ap [64] Osfael ap [65] Afloeg ap [46] Bran [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] Tybion ap [58] Edern ap [59] Rhufon ap [60] Dunant -

The Early Arthur: History and Myth

1 RONALD HUTTON The early Arthur: history and myth For anybody concerned with the origins of the Arthurian legend, one literary work should represent the point of embarkation: the Historia Brittonum or History of the British . It is both the earliest clearly dated text to refer to Arthur, and the one upon which most efforts to locate and identify a histor- ical fi gure behind the name have been based. From it, three different routes of enquiry proceed, which may be characterised as the textual, the folkloric and the archaeological, and each of these will now be followed in turn. The Arthur of literature Any pursuit of Arthur through written texts needs to begin with the Historia itself; and thanks primarily to the researches of David Dumville and Nicholas Higham, we now know more or less exactly when and why it was produced in its present form. It was completed in Gwynedd, the north-western king- dom of Wales, at the behest of its monarch, Merfyn, during the year 830. Merfyn was no ordinary Welsh ruler of the age, but an able and ruthless newcomer, an adventurer who had just planted himself and his dynasty on the throne of Gwynedd, and had ambitions to lead all the Welsh. As such, he sponsored something that nobody had apparently written before: a com- plete history of the Welsh people. To suit Merfyn’s ambitions for them, and for himself, it represented the Welsh as the natural and rightful owners of all Britain: pious, warlike and gallant folk who had lost control of most of their land to the invading English, because of a mixture of treachery and overwhelming numbers on the part of the invaders. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring. -

Breton Patronyms and the British Heroic Age

Breton Patronyms and the British Heroic Age Gary D. German Centre de Recherche Bretonne et Celtique Introduction Of the three Brythonic-speaking nations, Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, it is the Bretons who have preserved the largest number of Celtic family names, many of which have their origins during the colonization of Armorica, a period which lasted roughly from the fourth to the eighth centuries. The purpose of this paper is to present an overview of the Breton naming system and to identify the ways in which it is tied to the earliest Welsh poetic traditions. The first point I would like to make is that there are two naming traditions in Brittany today, not just one. The first was codified in writing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and it is this system that has given us the official hereditary family names as they are recorded in the town halls and telephone directories of Brittany. Although these names have been subjected to marked French orthographic practices, they reflect, in a fossilized form, the Breton oral tradition as it existed when the names were first set in writing over 400 years ago. For this reason, these names often contain lexical items that are no longer understood in the modern spoken language. We shall return to this point below. The second naming system stems directly from the oral tradition as it has come down to us today. Unlike the permanent hereditary names, it is characterized by its ephemeral, personal and extremely flexible nature. Such names disappear with the death of those who bear them. -

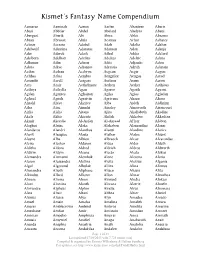

Kismet's Fantasy Name Compendium

Kismet’s Fantasy Name Compendium Aamarus Aaminah Aanon Aarlen Abantees Abaris Abasi Abblier Abdel Abelard Abelyra Abeni Abergast Aberik Abi Abira Abkii Abramo Abran Abrasax Abria Acamus Achar Achates Acknar Acrasia Adabel Adah Adalia Adalon Adalwulf Adamina Adamma Adamon Adan Adanja Adar Adarok Adath Adbul Addia Adelard Adelbern Adelhart Adeline Adeliza Adelric Adena Adhemar Adin Adiran Aditi Adjantis Adon Adora Adrac Adramov Adrestia Adrith Adurant Aedon Aedran Aedwyn Aegean Aegir Aegon Aelthas Aelus Aembra Aengrilor Aengus Aerad Aerandir Aerell Aergase Aerlson Aerne Aeron Aery Aesir Aethelmure Aethen Aether Aethicus Aethrys Aethylla Agan Agaros Agarth Agavni Agdan Agentes Aghairon Agika Agios Agladan Aglarel Agneh Agraivin Agrivane Ahazu Ahora Ahrahl Ahtye Ahziree Aiba Aideh Aidhrinn Ailsa Aine Ainmhi Ainsley Ainsworth Airancourt Airlia Aisha Aitana Ajira Akallabeth Akedine Akela Akhir Akienta Akilah Akkabar Akkadian Akmir Akordia Al-Asfan Al-Asraad Al'lyrr Alabon Alaghus Alaine Alaka Alakabon Alamanther Alanar Alandaros Alandri Alanthos Alaoui Alardine Alarice Alarik Alasquae Alasta Alathar Alatos Alaunt Alayne Alba Albion Albraech Alcae Alcarondas Alcira Alcolen Aldaron Aldea Alder Aldeth Alditha Aldora Aldred Aldrich Aldros Aldwerth Aldwin Aldym Aleana Alecto Aleda Alekos Alemandra Alemanni Alemhok Alene Alerena Aleria Aleron Alessandra Alethra Aletta Alexius Algania Algol Algorond Alhulak Aliiza Alina Alinnos Aliosandra Alioth Aliphane Alisen Alissia Alita Alkindus Allard Allister Allon Almar Almathea Almere Almira Almor Almund -

BERGER 1-Le Monde Celtique Des Premiers Siècles

ARSSAT 2014 85 SAMEDI 27 SEPTEMBRE « DE LA NAISSANCE DES CHRETIENTES CELTIQUES » PAR CLAUDE BERGER 1-Le monde celtique des premiers siècles. Le monde celtique est né autour de Hallstatt, en Autriche, vers le dixième siècle avant notre ère. Au premier siècle, il s’étend depuis la Galatie dans l’actuelle Turquie, jusqu’en Irlande et en Espagne. Il borde alors l’Empire romain, au nord. Les contrées suivantes en font alors partie : la Galatie, la Bithynie, la Thrace, la Mésie inférieure, la Dacie, l’Illyrie, la Dalmatie, la Pannonie, la Norique, la Rhétie, la Gaule Cisalpine, la Gaule Transalpine, l’Espagne Celtibère, la Bretagne, l’Irlande. 1 : Carte : Formation de l’Empire romain. (Atlas historique). Les Celtes sont un peuple de paysans et d’artisans. Ils ont domestiqué le cheval. Ils ont inventé la métallurgie du fer. Ils forgent l’or, le cuivre, le bronze et le fer. L’art celtique est florissant. Ceux qui vivent près des côtes fabriquent des navires et naviguent sur les mers et océans. Ils sont acteurs du commerce, entre la Méditerranée et l’Atlantique, commerce des minerais, du sel, du bois, des céréales, des vêtements, de l’huile, du vin, entre autres.. Cependant la population vit dispersée. Pas d’agglomération importante dans ces « Celties ». Les fermes de cette époque (l’âge du fer) sont isolées. Les regroupements ne se font qu’autour de gués, de marchés, de points d’eau permanents et ne sont dotés que de quelques habitations : moins de dix certainement. ARSSAT 2014 86 Il en résulte une densité moyenne de population de l'ordre de 3 habitants par kilomètre carré dans tout ce monde celtique, où cependant les régions côtières sont plus peuplées, jusqu'à 50 au kilomètre carré. -

On the Coins Forming a Necklace, Found in S

ON THE COINS FORMING A NECKLACE, FOUND IN S. MARTIN'S CHURCH YARD, CANTERBURY. AND NOW IN THE MAYER MUSEUM AT LIVERPOOL. By the Rei'. Daniel Henry Haigh, F.S.A.* (Read 2?th November, 1879.) " rpHERE was a church," says Ven. Bseda, " near the city of 1 " Canterbury, towards the east, made of old in honour of " S. Martin, whilst as yel the Romans dwelt in Britain." S. Martin died A.D. 397, the Roman domination in Britain ceased in 409, and the Angles came in 428; but many of the courtiers of the emperor Maximus, with whom, as his temporal sovereign, S. Martin had had very intimate relations, must have survived him, and to their veneration for his sanctity probably it was owing that a church was built in his honour, during this interval, almost contemporaneously with the erection of the earliest chapel over his tomb at Tours. When ^Ethelberht, king of Kent, received in marriage Bertha, daughter of Chariberht, king of the Franks, it was on this con dition, " that she should have leave to keep inviolate the rites of "her faith and religion, with the bishop Liudhard, whom her " parents had given to her as the helper of her faith ;" and to this church of S. Martin the queen was wont to repair for the exercises of religion, naturally preferring a church which bore * Written by the Rev. Daniel Henry Haigh for Joseph Mayer, F.S.A., to be read at a meeting of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. Mr. Haigh died suddenly, May, 1879. -

A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy...?

A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy...? An ecclesiological enquiry into metropolitical authority and provincial polity in the Anglican Communion Alexander John Ross Emmanuel College A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Divinity Faculty University of Cambridge April 2018 This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the Faculty of Divinity Degree Committee. 2 Alexander John Ross A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy…? An ecclesiological enquiry into metropolitical authority and provincial polity in the Anglican Communion. Abstract For at least the past two decades, international Anglicanism has been gripped by a crisis of identity: what is to be the dynamic between autonomy and interdependence? Where is authority to be located? How might the local relate to the international? How are the variously diverse national churches to be held together ‘in communion’? These questions have prompted an explosion of interest in Anglican ecclesiology within both the church and academy, with particular emphasis exploring the nature of episcopacy, synodical government, liturgy and belief, and common principles of canon law. -

Evangelical Work Should Be Kept in Evangelical Hands." Evangelical Principles Do Not Change

34 Episeopacy in England and Wales. As for its spiritual teaching, the maxim of the Founders is a wise one : " Evangelical work should be kept in Evangelical hands." Evangelical principles do not change. It would, there fore, be folly to part with the old lamp which gives Ught, and which has elicited treasures, for new ones, which may or may not give light. Folly to drop solid meat into the water for a vague reflection of something which looks like meat but may not be. :Folly to part with a present stock of provisions, though small, and a cruse of water which have not failed the Church at home or the heathen abroad, for a glowing mirage, which, when it is reached, may prove to be barren sand. GEORGE KNox. N OTE.-Since the foregoing was written and placed in the hands of the Editor of THE CHURCHMAN there has been a long debate in the Upper -House of Convocation (Feb. 14). The practical resnlt may be summed up by stating that no agreement could be come to by the Bishops on the schemes before them. Serious and complicated objections of all sorts presented themselves. The whole subject is to be taken up de nova in accordance with a motion of the Bishop of Lincoln, to the effect that "A general committee of both houses be appointed to consider the subject of the Board of Missions, and that his Grace the Archbishop of York and the Northern Provinces be invited to nominate a committee of their Houses to confer with a joint committee: and that this resolution be communicated to the Lower House and to his Grace the Archbishop of York." In the terseness of military parlance this is tantamount to "As you were" twelve years ago. -

AN INTRODUCTORY HISTORY of the ORTHODOX CHURCH in BRITAIN and IRELAND from Its Beginnings to the Eleventh Century

1 AN INTRODUCTORY HISTORY OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND From its Beginnings to the Eleventh Century By Aidan Hart PART I (until 600 AD) “In all parts of Spain, among the diverse nations of the Gauls, in regions of the Britons beyond Roman sway but subjected to Christ... the name of Christ now reigns.” (Tertullian in “Adversus Judaeos” Ch. 7, circa 200 AD) Introduction There is a saying on Mount Athos that it is not where we live that saves us but the way we live. This is a play on the Greek words topos and tropos . One could add that neither is it when we live that saves us. And yet on reading the lives of saints who lived in other epochs and other lands it is easy to feel that it is impossible for us, in our circumstances, to approach their level of repentance and humility. This is one reason why many British and other English speakers are being attracted to the saints of the British Isles: although these saints lived over a millennium ago they lived on our own soil, or at least on that of our ancestors. It is as though these local saints are not only supporting us from heaven, but are also with us here, on the same soil where they once struggled in the spiritual life. How eagerly the saints of Britain must await our prayers that the land in which they so mightily laboured should again become a garden of virtue! It is difficult to be inspired by saints about whom we know little.